- Old Draft: Beatles Folk Memory 1970-1995 - December 8, 2025

- Lights are back on. - December 8, 2025

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

[Folks, this post may be a little rough because I’m having real trouble typing into the WordPress backend. Forgive any typos, etc.—MG]

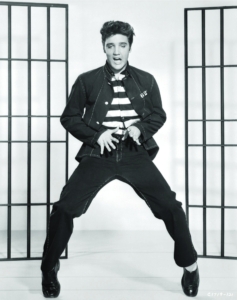

Elvis the Pelvis comin’ at ya

I’ve never seen Elvis’ breakthrough 1957 movie, Jailhouse Rock, because truth be told, I’m not the world’s biggest Elvis fan. But I decided to watch it, specifically with an eye towards comparing it to A Hard Day’s Night just seven years later.

We talk a lot about masculinity here on Dullblog, and The Beatles’ relationship to older models of manhood. The first thing that struck me about Jailhouse Rock was the inciting incident: Elvis is sent to prison for killing a man in a bar brawl. Of course he had his reasons—he was defending a B-girl from some cad (her husband?) who wanted to rough her up—but right from the start, we see this movie lives in a vastly different world. A world by and for grown-ups. A world of grown-up actions (drinking, fighting) and grown-up problems (dying, jail). It’s as if AHDN was set in Hamburg, and Paul accidentally beat someone to death. “What do we do, Shake?” “Time, Paul. Hard time.”

Then, 24 minutes in, Elvis is punished in his part in a prison riot by being stripped to the waist and lashed. Elvis snarls and squirms beatifically, in a scene worthy of Beatles fanfic.

Compared to this harshness, this brutality—“Hey, let’s make the latest teen heartthrob a murderer, stick him in a brutal Southern prison, and show him being tortured”—AHDN seems like it’s inhabited by a quartet of grown-up children. The stakes are also childlike: whether the show comes off on time is, from an adult’s perspective, almost totally immaterial; after all, we (and they) know that they are The Beatles, one of the most popular acts in the world. Victor Spinetti will live if they have to swap in something. AHDN’s tension is really “will Ringo still be friends with the other Beatles, or will he stay mad at them for making fun of his nose?” What is it about the magic of The Beatles that allows us all to look past this nonsense?

Elvis, in Jailhouse, is unquestionably an adult, doing adult things, paying adult penalties. He appeals to kids, but he isn’t one of them, and he’s not even a stand-in for them. He lives in the same world, the same version of masculinity that had 18-year-olds getting jobs, raising families, going off to war.

The whipping embitters Elvis; where he was formerly deferential to authority, he now sneers at the Warden: “You’ve been just like a father to me, sir.” I immediately thought of the scene with The Beatles in the train-car, where they spar with the stuffy businessman. Unlike Elvis, we’re not shown The Beatles suffering unjustly before this scene; their antagonism isn’t personal and earned—it’s reflexive, generational. And it’s so widely felt throughout the Boomers that audiences didn’t even question it. The Beatles—standing in for their much younger, much less worldly fans—mouth a kind of generalized alienation that, in 1957, you’d find in poems like HOWL…but not in the teenybopper set. By ‘64, that alienation had percolated throughout the culture, on both sides of the Atlantic, and had been turned from a critique of postwar consumerism into a sort of acid cheekiness. When George puts down the TV star, he’s not mad at being commodified, catered to as a demographic—and once again, it’s not his demo, but a much younger one—he’s mad that she gets it wrong.

After getting out of the slammer we see Elvis check into a fleabag hotel; he then takes some of his prison wages to a pawn shop and buys a guitar. In the next scene, he’s at a club (quite possibly a strip club), looking for a job. A pretty song-plugger sits down next to Elvis, but he’s only interested in the mechanics of the business. He’s a brusque asshole.

When the owner brushes him off, he leaps up on stage and sings a number. Then, he leaps back down and smashes his guitar basically AT a bar patron who laughed while he was singing.

So: it’s no surprise that a young John Lennon saw this dude and felt kinship. The ironic thing is that when Lennon had achieved his dream and was part of his own Jailhouse Rock, his rebellion was sniffing carbonation from a Coke bottle or writing “TITS” on the pad of a reporter. It must’ve felt pretty light and silly to him; childish, even. But that’s what I’m feeling more and more: Jailhouse Rock was an old-fashioned rags to riches musical, a tale of morality, that just happened to star Elvis; AHDN was a very finely crafted children’s movie. This is why I think critics were so quick to make a comparison to the Marx Brothers. Like the Marxses, The Beatles were talented and tortured grown ups playing like children—but unlike the Marxses, The Beatles are stuck in a setting that pretends to be their real life. There is no love interest in AHDN, so the audience can play that role.

We next see Elvis recording a demo; and then, when he’s unhappy, doing it a new way—discovering his special sound. “Sing it how you feel it,” Peg the song-plugger says. “Put your own emotions into the song, make it fit you.” In other words, assert your own taste, your individuality—the seed that sprouted a whole new kind of pop culture…including The Beatles. Armed with this song from his soul, Elvis and Peg then go around to record companies trying to get them interested. In some ways, Jailhouse Rock is basically a how-to; AHDN is what’s waiting for you when you make it.

When the song plugger sells the record—to a new label looking to make its mark—Elvis basically negs her. Peg buys dinner. Peg then takes him to a party with her parents—who don’t even buy an eye at Elvis’ criminal record. They put on some jazz, and namedrop Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond. When they ask Elvis’ opinion of jazz music, he says, “Lady, I don’t know what the hell you talkin’ about,” and walks out. Peg follows him out, and gives him a piece of her mind. He responds by grabbing her and kissing her. Elvis is, in a word, an asshole. Jailhouse Rock is real old-fashioned toxic masculinity.

Not only are The Beatles not assholes in AHDN, they certainly aren’t walking around redpilling women with insults. As I said, they’re not kissing women at all. They like women but—like teenagers under the careful eye of adult authorities—can never express those feelings. Elvis is a jerk—“it ain’t tactics, honey; it’s just the beast in me”— but also unquestionably an adult.

Elvis’ record comes out—but it’s been re-recorded by the label’s big, bland star, Mickey Alba. Elvis has been screwed! He goes to the label and slaps the owner of the label. “Go back under your rock, you snake!” Imagine the same thing happening in the Beatles’ movie—them striding into Swan or something, and beating the hell out of them for not pushing “She Loves You.” Inconceivable.

Elvis decides to start his own record company, and Peg quits her job. They find a lawyer, and make him Elvis’ manager.

Until now, all the songs in Jailhouse Rock—I feel I should mention them—all sound the same, to me at least. According to the credits, most of them were written by Lieber & Stoller, but I’d be surprised if they spent more than a long weekend.

We see the couple hoofing it around, trying to sell Elvis’ record; and Peg uses her connection with a friendly DJ to get the record played…as the background to a dog food commercial. (Can you imagine The Beatles’ material being treated in this way in AHDN, as satire?)

Fans call in, and he plays it. It’s a huge hit! Elvis is a star!

There’s a whole romantic subplot that’s Hollywood 101.

The famous scene—and only great song in the movie—is “Jailhouse Rock,” and exactly the kind of singing-dancing extravaganza that The Beatles make fun of in AHDN. They may be kids, rather than adults, but they are wised-up kids. The Beatles’ version of this number is probably the field scene, where they…act like kids.

Elvis goes to Hollywood—“Climax Pictures” is a moniker worthy of Terry Southern’s Blue Movie—and Elvis and a bored starlet see the sights in a sort of wan parody of fame culture.

By this point in the movie, we’re seeing Jailhouse Rock turning into AHDN—Elvis is shown acting in a movie, but he kisses the starlet and she falls for him. There’s actually “Tender Trap” playing in the background—a piece of the kind of music that Elvis and his fans were destroying—which is utterly unthinkable in AHDN. By the time of AHDN, the revolution was complete, and playing another kind of music could only be done for laughs, as the rehearsing dancers flop and caper.

Elvis is portrayed as a big-shot movie star, whose friends think he’s gone show biz. He’s cruel to his old cell mate. The last 20 minutes or so are about a record deal, and Elvis is a money-grubbing asshole.

After Elvis forces Peggy to take the buyout deal, his old cellmate beats hell out of him, hitting him in the throat. An ambulance rushes Elvis to the hospital, to the strains of dramatic music. Will Elvis ever be able to sing?

Not fighting back in the fight “was an act of true love,” Peggy says to a silent Elvis. “Don’t be afraid to love.” I imagine the young Beatles hating this part, and the distance between melodrama like this and AHDN is the distance between the Old Showbiz of the 50s and the New of the 60s.

In the climatic scene, Elvis sings in a whispering voice that strengthens; it’s a private moment, a private victory. Compare the final scene of AHDN—which is never in doubt—a public performance with the Fabs performing for us, their playmates, their companions, their only lovers, their adoring audience.

Only tangentially related to your (excellent) article, but generationality and Elvis films v Beatles films remind me of something Danny Peary wrote in Cult Movies (1981):

“A Hard Day’s Night” was one of the truly pleasant surprises of the sixties: a breezy, captivating, joyous film made during a particularly dreary movie period; a guaranteed box office hit that turned out to be an artistic success as well. The splendid reviews that the picture received and the unexpected praise heaped upon the Beatles for their performances made the nation’s young people collectively burst with pride. To have their Beatles, their idols who were more than symbolically central to their lives, given “legitimacy” by establishment critics, whom their elders/parents read and respected, was much more than gratifying — it was liberating. I am serious when I say it is the only time on memory when young people could point to “proof” in writing (reviews) and tell their condescending elders: “See! I am right about something, and you are wrong!” What an earlier generation of Elvis admirers would have given for such testimonials. A Hard Day’s Night gave America’s youth a “moment of triumph” which they, as adults years later — balding and grating perhaps — still cherish.”

Albert Goldman has a lot of fun analyzing the Jailhouse Rock movie in his Elvis biography. The whipping scene, the scene where Elvis’s record is re-recorded, the sexual tension. Goldman picks through that whole cinematic endeavor like a hungry, sardonic bird.

I am resolved… resolved, I tell you… not to turn my response to this into an article, so it will be an extended comment instead…

When Michael shared some of his initial HDN vs Jailhouse Rock thoughts with me, I went back and re-watched both movies back-to-back, followed by Rebel Without a Cause and On the Waterfront, because Marlon Brando is listed by three out of four of the Beatles as their favorite film star on an early questionnaire, and both Brando and Dean are often cited as primary cultural influences, particularly for John, but also for Paul.

A few thoughts then, in no particular order:

As Michael observes, the script for Jailhouse Rock unquestionably attempts to portray Elvis as a tough macho He-Man, but even a casual observer can see that Elvis doesn’t even remotely pull off the casting. He’s woefully miscast in that role, because he’s way too soft to be that guy. I think Michael’s right that Colonel Parker and Hollywood were trying to position Elvis as this ultra-manly leading man, but it was a misstep and I think it’s a big part of why Jailhouse Rock doesn’t really hold up today, except for…

…the actual Jailhouse Rock performance, which may not have been to the Beatles’ taste (minus, y’know, all the times they did similar stuff… MMT, for one…), but you can see in those three minutes why Elvis was what Elvis was. The movie is skippable, but that sequence is one of the most electrifying on-screen performances in music history.

Related to all of this, neither James Dean nor Marlon Brando is especially off-the-charts masculine, either. It’s interesting to me, and I think hugely significant in terms of the Beatles image, legacy and cultural influence, that all of the so-called “macho” role models that John sought out to fashion himself after aren’t actually very masculine at all, but softer, more sensitive men who postured as masculine in order to satisfy the demands of the culture (both within the movie and the larger actual culture). Unlike Jailhouse Rock, the roles that Dean and Brando play in Rebel and Waterfront are men who are forced into being tougher than they are in order to fit in/win social approval/survive.

The Beatles are unique in that, starting in ‘62, they stopped posturing altogether and (thankfully!) seem to have embraced this softer, more sensitive version of masculinity. And then continued to embrace it more and more, as they all became progressively softer and, at the very least, more gender neutral (but I’d argue more feminine) throughout the trajectory of their Beatle years. I’d say there’s a strong case to be made that they never really embraced hard core masculinity at all, even in the beginning when they were rocking harder than any other band on the plane (I submit the art school influence, the primary influence of American girl groups and the pink twat hats in Hamburg into evidence), but early on, they did seem to be trying (like Dean and Brando and Elvis did) up until ‘62 Brian enters the picture.

The Beatles’ having rejected this kind of faux uber-masculine posturing is IMO a big part of why they endure. And I think a lot of the credit for this goes to them being across-the-board mentored and shaped by softer men. Unless I’m missing someone, there isn’t an influential hard-core “he man” of any significance anywhere in the Beatles’ story — Stu, Bob Wooler, Larry Williams, Robert Fraser, Peter Asher (and Papa Asher and I know I’m skipping over some others) , and of course, the Big Three — the Exis (I’m including Astrid here, of course), Brian and George Martin… none of the Big Three were hyper masculine. All of them, particularly the Big Three, presented varied but very defined softer versions of masculinity (or in Astrid’s case, androgyny).

As to the love interest part, it’s worth noting that despite their (half hearted) efforts, there’s really no credible love interest in Jailhouse Rock, either — from my perspective at least, Elvis has zero chemistry with the female lead in Jailhouse Rock and barely seems interested in her for anything other than career advancement. But the filmmakers certainly do try for it, even if it doesn’t really come off. Maybe he sparks better with female leads in his other films, where he comes across as a bit softer? I haven’t seen the full Elvis film collection, so I can’t speak to that.

On the other hand, there is absolutely a love interest in Hard Day’s Night, and it’s Paul McCartney, who is presented in all of his glorious, impeccably tailored and quoiffed, Cupid Bow lipped, doe-eyed, rounded-hip metrosexual glory, and is treated, cinematically-speaking, to the same Hollywood glamour close-ups, blocking and framing that the leading female sex symbols of the day were given.

More broadly, the “couple” in Hard Day’s Night is John and Paul. Now before anyone gets their knickers in a twist, consider that this theory has merit regardless of your opinion on the nature of their relationship. They’re not “buddies” in Hard Day’s Night (or anywhere, really) — the “buddies” in Beatledom and in HDN are the four of them together. John and Paul as a couple in Hard Day’s Night (and in all of their concert footage and pretty much everywhere) spark like Bogie & Bacall or Hepburn & Tracey — we know this and so did the filmmakers. A love interest would have stepped on their chemistry, which I suspect is the larger part of why Paul’s scene with the Shakespearean actress was omitted (as a former casting director, I’m not seeing that he’s any worse an actor than John or George). An extended scene of Paul flirting with a girl/woman would have stepped on the John and Paul dynamic, and thus on the romantic pairing of the film.

Another way to look at the love interest question is to point out that unlike Elvis, the Beatles are a complete unit, a closed circle, the “four headed monster.” Introducing a love interest would break that closed circle, which would be psychologically disorienting and absolutely off-brand. (If you haven’t seen the stills from Paul’s HDN scene, they’re here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ka2D7zogwZI and the script is here: http://www.beatlesinterviews.org/dbhdnscene.html

Three more notes relative to Michael’s article:

Hard Day’s Night is a kid’s movie only in the sense that Alice in Wonderland and The Little Prince are kid’s books, and Yellow Submarine and Octopus’ Garden are kids songs. Which is to say, far from it but they hide their adult content within that veneer, certainly.

Pivoting momentarily to Rebel Without a Cause, given its reported influence on John, I couldn’t help but wonder as I watched it if, in addition to John seeing Elvis in Paul when they first met, he also perhaps saw a bit of Plato (the Sal Mineo character). I see an awful lot of youthful pre-fame John and Paul in Rebel’s Jim and Plato.

I haven’t yet read a prison scene of any kind in Beatles fanfic, which is a tragic missed opportunity, particularly with regard to the Piglet/Hedgehog incident that resulted in all four of them being temporarily jailed in Hamburg. As a passionate Beatles fanfic writer/reader, I may need to go write one…

@Faith, I’ll need quite a bit of convincing to believe that A Hard Days Night, and HELP too, are not kids’ movies. I don’t think The Beatles, Brian, Dick Lester, or UA thought for a second that the picture was for adults (people over 18), and while you as an adult might find themes that resonate for you in it, I think AHDN and Help are wonderful examples of something Devin unpacks in Magic Circles: the infantilization of the four of them by the American publicity machine. They do nothing in AHDN that signifies them as adults, but regularly play like children (“Mister, can we have our ball back?” John in tub, the field sequence which is ended with a childlike line, “Sorry we hurt your field Mister”, and so forth). And the young fans’ favorite, Ringo—the mascot, the most harmless, most approachable, least conventionally attractive—is at the center of both movies.

The whole point of The Beatles in these movies is that they are not adults, but a teenager’s idea of what the perfect adulthood might be. The Beatles are a grownup version of the gang many of us have as teenagers, but lose after high school or college, when the cares and circumstances of adulthood (not least sex!) pull us apart.

The idea that J/P subtext functions as a romantic subplot—something similar to Peg and Elvis—I’d need sources/criticism prior to the internet that assert this to consider it. I’d argue that it’s the romance of the four of them for each other that is the obvious analogue to Peg and Elvis, and “will that friendship survive?” Gives AHDN what little drama it has. If that’s the emotional center of the movie, and I think there’s ample evidence that it is, J/P literally cannot be present in the movie, any more than J/G, P/G, G/R, etc etc.

The whole point of The Beatles in the two Lester movies is that they are non-sexual—that’s another reason why people compared them to the Marxses. The movie Beatles, like the Marxses, deal in frustrated sexuality—like teenagers do.

AHDN couldn’t have a true romantic angle because it breaks the fundamental dream of the movie, which is that The Beatles are available to us; that they are as interested in us as we are in them. Viewing AHDN, we are The Beatles’ special friends. “Women want to have them, men want to be them.”

I think Help! and AHDN were both kids’ movies, but like most kids’ movies there are bits that are aimed for adults’ amusement.

I saw both films in a theater when they first came out, and Help’s sly jokes between the mad scientist and his bumbling assistant went right over my head (I was seven years old and loving the music and silly stuff), jokes about the quality of postwar England’s technology, etc. And in AHDN there’s that great scene of George wandering into the conference with the “opinion maker” who tries to impress him with his latest TV celebrity. That stuff went right over my head as well.

In Help! there is a scene where Eleanor Bron (as Ahme) tries flirting with Paul and he responds with a disapproving scowl. That’s what I would have done when I was seven! The Beatles are big kids in both films. But I think that’s great, it adds to the surrealism of the experience.

Incidentally, I remember the audience of girls screaming during AHDN. A group of John fans screamed whenever he had a closeup while a group of Paul fans screamed whenever Paul’s face filled the screen. It was almost like being in a Beatles concert. I remember it making quite an impression on me.

@faith “as a former casting director, I’m not seeing that he’s any worse an actor than John or George”

Thank You!!

It’s so weird to me that the received wisdom is that Paul is such a laughably terrible actor. Why? I think his wooden performance in Give My Regards To Broadstreet is partly *because* he ended up with this reputation as being overly-keen.

Ringo’s laugh at the end of his (first?) line in AHDN is so badly delivered it makes me laugh every time. I haven’t watched any of his non-Beatles movies, so I won’t comment on his acting skills more generally, but Paul doesn’t stand out to me as worse than any of the others. It feels good to know I’m not completely alone in that take 🙂

“Paul doesn’t stand out to me as worse than any of the others. It feels good to know I’m not completely alone in that take.” I’m in the same boat – he seems fine to me for a non-actor. I started reading the script for his deleted scene and… it’s pretty awful, isn’t it?

I wonder how much of that shift was driven by the fans.

I remember reading an interview (I can’t remember if it was John or Paul) about the early days of the band. They’d been wearing their leather gear onstage like a group of little Gene Vincents. One day they noticed girls in the audience laughing at them. Not long after that they abandoned their leather for something less stereotypical.

There’s footage of a Gene Vincent performance from 1959. He wears a v-neck pullover sweater, a real Frankie Avalon style, because leather suits and the dazzling florescence of bright green and red jackets had become passé by the late ’50s. Rockers in America were switching to suits and sweaters.

In 1960, when Gene Vincent traveled to the UK for a tour with Eddie Cochran, the promoter was confused and disappointed by Gene’s smart-looking v-neck and pressed slacks. “But you’re Gene Vincent! Your fans here expect leather!” So Gene and Eddie switched to leather suits to satisfy British kids’ expectation of what “exotic” American rockers should look like.

The Silver Beatles got away with that fashion for awhile, but it eventually became as passé as it had become in the States. And so the UK girls laughed them out of their leathers and into a less macho image.

I think Brian did the right thing when he encouraged that transformation.

Lester said that Paul was first uncomfortable but warmed up during filming. He took out the solo scene of Paul because it was too sexy and was not in plot with the film (plot you say?). Paul was too attractive, sexy in his scenes that – same thing in Help! They didn’t want any of the Beatles to come off as sexy. Brian Epstein was concerned with Paul filming alone with a sexy woman and that the fans would be very unhappy to see him so flirty in AHDN so they cut it. But Lester said it was one of his favorite scenes.

I’d wondered why everyone but Paul got a standalone scene in AHDN! That said, George’s scene there is pretty flirty, so I’m not sure I understand that reasoning.

Did Paul’s scene ever get released as an extra?

I really enjoyed that scene in the book adaptation. I’d love to see the version they filmed 🙁

I recall Dick Lester saying he cut Paul’s scene with Wendy Richard (who later played Miss Brahms in the British sitcom Are You Being Served) because he was too self-conscious. Paul may also have felt uncomfortable considering his romance with Jane Asher started to get serious around that time. I also recall John saying he and Paul could barely look at each other during their lines for fear of collapsing into helpless laughter because they felt so embarrassed. He was later dismissive of Alun Owen who wrote the screenplay for the film. I may be wrong, but I get the impression that some younger fans believe that the Beatles wrote their own lines, although undoubtedly they adlibbed at times. I honestly didn’t see any romantic connection at all between John and Paul in A Hard Day’s Night. What I vividly remember though, were the more sexually mature girls screaming their heads off when either of them appeared. @Faith, you mentioned Paul’s ’rounded’ hips, a confusion perhaps with the minor structural abnormality of him having bow legs. It’s a trait that’s not specifically male or female. Of all the millions of photos of Paul, I surely can’t be the only one to have noticed his bandyitis that when he puts his feet and ankles together his knees don’t meet in the middle. A gap wide enough for a rhinoceros to charge through.

A Hard Day’s Night wasn’t made for adults but it wasn’t made for children either. It surprises me how many people say they were eight or five or whatever when they saw the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan show. The rock music press from 1970 were very keen to present the Beatles as a band for teenyboppers (ie 10-12 year-olds) once the bloated reverence for rock music established itself. This simply was not true. Growing up with them at the time, the average age of fans during peak Beatlemania was nearer to 15 or 16 rather than nine or ten. One only has to look at the film footage of concerts to see that there were relatively few children in audiences globally, a fact the Beatles themselves were well aware of. Notions of a hot or attractive one were too challenging for a puritannical America in 1964, so what better way to circumvent it by ascribing the cute moniker to Paul. But we knew what they meant… @Baboomska McGeesk, you are spot on about the leather suits. I’d like to add that to British people, the boys in their leather gear made them look like watered down English versions of Marlon Brando and Gene Vincent. Nobody wanted that. What Brian Epstein did above all in 1962 was to establish not so much a softer look, but a very British/European identity that British kids could call their own.

Lara, I was six years old in 1964. I was too young to fit the profile of a Beatle fan. I know my classmates weren’t as impressed with them as I was, the Monday after the Ed Sullivan appearance.

I think the only reason I became so Beatle crazy at that age is because I had two much older siblings, teenagers. They bought albums and 45s and so the early Beatles were constantly playing in our house, as were the Dave Clark Five and The Searchers.

After a few years my siblings “outgrew” the Beatles but I remained hooked.

If I’d been an only child I probably wouldn’t have heard so much of that music at the time. I probably wouldn’t have gotten into JPG&R until I was a stoner teenager in the 1970s.