- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

NANCY CARR * What Beatles fan who was alive in 1980 hasn’t wished he or she could have done something to prevent Lennon’s murder? And what thoughtful Lennon fan hasn’t been troubled by the contradictions manifested in Lennon’s personality and life? Those questions drive Phil Rickman’s 1996 novel December, a worthy read for this time of year despite its flaws.

The book’s action starts on December 8, 1980, not at the Dakota in New York City, but at a decrepit abbey in the Welsh countryside where a band fraying with tension has gathered to record a new album. One band member, Dave Reilly, has psychic powers that manifest as voices in his head, and as he stumbles around the snowy woods he repeatedly hears “This guy is dying”— words allegedly spoken after Lennon’s shooting by the building workers who called the ambulance. But as he figures out afterward, he was hearing it four hours before the shooting occurred. Dave’s efforts to make sense of this, and to work out his own love/hate feelings toward Lennon as a musician, are the heart of December.

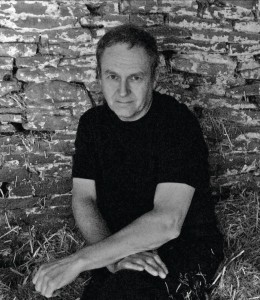

December has significant limitations. There is too much cumbersome plotting, which is less interesting than the characters deserve. Some scenes drag, and at 645 pages, this is a long novel that would be better as a trimmer one. Rickman’s fascination with the paranormal can also lead him to stretch credulity too far: for instance, a whole band that has genuine psychic powers? In sum, at this point in his career Rickman (best known for his later novel series about Anglican exorcist Merrily Watkins) is still finding his way as a writer. However, December’s characters—especially Dave and Prof Levin, a recording engineer determined to release the “Abbey Tapes” despite the disasters that befell the band in 1980—are strong enough to overcome the book’s defects.

Dave enters the book stumbling around aimlessly, and that’s what he does for a good deal of the novel. He is haunted by the feeling that he could have done something to warn Lennon, so much so that he is literally haunted by Lennon’s voice in his head and carries on dialogues with him. After Philosopher’s Stone (the band) splinters at the end of 1980, Dave makes a living playing shows that parody great figures in rock—Bob Dylan, Neil Young, and especially Lennon. Prof Levin is nauseated as he watches Dave send up “Imagine,” but recognizes that Lennon is the only rock figure who is causing Dave “personal pain.” Later in the book Dave tells former bandmade Moira about writing “On a Bad Day” early on December 8, 1980. The song is a scathing take on 1980 Lennon in which Dave voices the disappointment many initially expressed about Double Fantasy. He tells Moira he recorded the song the morning of the 8th at the Abbey, which the band had chosen as a venue because of its supposed ability to amplify psychic powers. The conversation that follows shows Rickman doing what he does best, exploring moral ambiguities through believable characters:

“Mark Chapman’s never been the quietest, most retiring of lifers,’ Dave said bitterly. He’s always going on about how he might not have shot Lennon. Earlier the same day he went along to the Dakota and asked John for his autograph on a copy of Double Fantasy and then went away again and thought about not killing him.”

“He’s bonkers, Davey. He’s a headcase.”

“Also, he kept on about hearing voices in his head. The Little People he called them.”

“Davey, every fruitcake killer claims to hear voices. The Yorkshire Ripper, all those psychos . . .”

“And while he’s thinking about it, agonizing over whether to go through with it, a song echoing all his Catcher in the Rye sentiments is being laid down with a lot of malice aforethought . . . ” (422-23)

Rickman’s emotional investment in the issues he’s exploring here is indicated by his getting a band together to record songs “by” Philosopher’s Stone: you can listen to “On a Bad Day” here and “Dakota Blues” here. It’s to Rickman’s credit that the novel doesn’t offer easy answers, and that it critiques its own fascination with coincidence and the paranormal. Rickman makes much of the Liverpool power cut of December 13, 1993 (13 years since Lennon’s murder, on the 13th day of December, 13 minutes past the hour), but his characters also realize that it’s crazy to focus on this kind of thing.

Rickman knows that what ultimately matters is the music, and that’s why Dave is so torn apart by having written and recorded “On a Bad Day” (which he refers to as as “a bit of a pastiche of ‘How Do You Sleep?” (421)). Positive or negative, the emotional power of music can’t be cut, and with such power comes responsibility. Overall December is a somber read, which is only fitting. I return to it for its willingness to grapple with the kind of questions about Lennon and his music that just won’t go away, no matter how many years have passed since 1980.

Thank you for alerting me to this, Nancy. I’m having one of my recurrent immersions right now in the golden age of the English ghost story and “weird tale” (Bulwer-Lytton, Dunsany, Machen, Blackwood), many examples of which, both novel and story, are also excessively plotted and overlong. So this one sounds right up my alley, with the added plus of the Beatles connection.

If you do read it, Devin, I’ll be interested in hearing what you think of it.

I also love English ghost and “strange” stories, especially M.R. James, Blackwood, H. Russell Wakefield, and Robert Aickman. I’m currently rereading H.P. Lovecraft, whom I also enjoy, though in smaller doses.