- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Why pick an Isley Brothers song for the title?

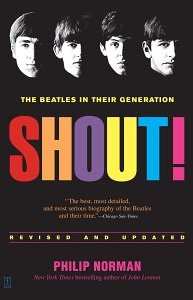

Yesterday evening, I was perusing Shout! and, as ever, thought it was a really great, fluid, surprisingly no-nonsense large-grain history of the group. Well, maybe “really great” is a bit much, given the book’s anti-Paul bias, but it’s still wonderfully written, and was essential in its time. If you were a Beatles fan in the early 80s like I was, Shout! was the companion volume to The Compleat Beatles. I’m looking forward to comparing it with Davies, as soon as I can lay my hands on that book. (It’s not really fair to compare Shout! with Spitz, as Spitz’s book came after a couple of decades of further research, and is much less impressionistic.)

Anyway, Shout! led to Norman’s John Lennon bio, a beach I’d attempted to storm more than once without success. It always seemed like the story we’d all heard a million times before, albeit fleshed out with some pretty awesome new quotes (which I suspect come from tapes Lennon made in the late 70s, as he prepared to write an autobiography). The book’s history with The Estate–first smiled upon, then not–made me highly skeptical about its objectivity, and lo and behold, that was the primary complaint when it appeared. Cooperation is a great way to guide a manuscript–to keep pressure on an author–and withdrawing support after the manuscript is finished is a great way to keep the power. There is simply no need for this kind of behavior; if John Lennon’s important enough to merit an 817 page book, he’s important enough for everybody to shelve their egos for a bit and GET IT RIGHT. Unless that’s not the point. It may not be, at least from The Estate’s point of view.

A fatuous feud that diminishes everybody concerned

Every page of John Lennon: The Life seems to emphasize certain Estate talking-points: John as rebel, Paul as authority; John as genius, Paul as sidekick. This simplistic view has been refuted by so many works it’s simply not defensible any more. Worse than that, it’s totally unnecessary, stoking a fatuous feud that does nothing but diminish everybody concerned. After all this, the section with Sean turns the poor guy into just another talking-point: Sean as Brand Extension, which demeans the father and stunts the son. Who knows what neat things Sean might do, if he could actually exist in the context of himself? He has that right, and I hope he gets it someday.

All this having been said, last night’s dipping in to John Lennon: The Life was altogether more successful; I started around the end of the first Hamburg trip, and spent the rest of the evening reading. I think perhaps Norman’s slightly operatic writing style only works once The Beatles’ story is exciting enough to merit it.

Last night I read about Stu Sutcliffe’s death; this morning I read about John and Brian’s trip to Spain, and Lennon’s subsequent punch-out of Bob Wooler. In each of these instances–some of the most hotly debated in Lennon’s life–I was struck by how little Norman’s portrait of Lennon deviates from Albert Goldman’s.

Norman vs. Goldman: more similar than different?

Whatever one might say about The Lives of John Lennon, its primary revelations in the case of these three events are not strongly refuted in Norman. While Goldman assumes the worst, Norman tries to put the least controversial face on it. Of course I wanted the issues resolved, and Norman simply does not do that.

The source for the “John kicked Stu in the head” story is revealed to be Stu’s sister Pauline, who says her brother told her during his last visit to Liverpool. That seems like a pretty heavy source. Here’s how Norman handles it:

- Paul, who was supposedly there, says it’s possible that John attacked Stu, but doesn’t remember it. Of course, the question any biographer should then ask is, “Would Paul admit it if it actually had happened?” There is NO WAY Paul would do this; it would be tantamount to calling his ex-partner a murderer. This would be massively damaging to McCartney’s own career. People get pissed when the guy credits songs he wrote to “McCartney-Lennon”!

- Astrid, who was supposedly the cause of the fight, doesn’t think it happened, because “Stuart would’ve told me.” Hmm. If your best friend beat you senseless because he wanted to steal your girlfriend, would you tell her? Probably not–and if you thought there was any chance she’d be happily “stolen,” you definitely wouldn’t.

- Then “other people close to them both at the time are reluctant to believe” that John attacked Stu. Without attribution this is impossible to judge, but in any case it’s almost meaningless. What purpose would speaking ill of the dead possibly serve?

If you’re reading this blog you are–like me–really hoping that John didn’t attack Stu, or if he did, did not contribute to his death. But our hopes aside, there was a vast swath of self-hatred in John Lennon, as well as a fierce desire to prove, achieve, outrun, defeat; the knowledge (or belief) that he contributed to his friend’s death would explain those traits quite succinctly. It’s not the only thing that would–Julia’s death and his parents’ neglect might, too. But as a motivation, it feels internal and human, not like a myth, a legend, PR.

The Beatles as more than celebrities: human beings

Goldman: just a different myth, not the truth

Any reasonable discussion of The Beatles’ story has got to start from the point that these guys were human beings; when they were insecure teenagers, they acted like insecure teenagers. When they took drugs, they experienced the same effects–negative and positive–that other people do. The tendency to gloss over this reality is, to my mind, one of the most damaging aspects of The Beatles’ mythology. Harrison famously said that one day he realized that “anyone could be Lennon and McCartney,” and he would know. To marvel at their singularity, and stop there, takes an opportunity to learn about life and ourselves and turns it into…showbiz.

Of course the difference between Goldman and Norman is Goldman’s palpable glee in destroying the Lennon myth for destruction’s sake. I don’t have much use for that, and think it mars the book horribly, making Goldman’s primary contribution — his research — seem less valuable than it has proven to be. It’s a shame that Goldman had no compassion for his subject, because it’s Norman’s fundamental sympathy towards Lennon which makes the portion that follows Stu’s death simply heartbreaking. He quotes a letter from Astrid to Stu’s mother, Millie:

“One day [John] showed me and Klaus [Voorman] his little room. Every piece of paper from Stuart he have [sic] on the wall and big photographs by his bed.”

Does Norman want us to come to our own, dark conclusion? I wonder, and I wonder such things regularly throughout the book, as Norman trots out this or that example of Lennon’s bad behavior. But it must be said, in each of these three cases, the source for the darker portrait is Lennon himself. For Wooler, Norman turns Lennon’s “I could’ve killed him” into “bruised ribs and a black eye.” For Spain, Wooler refutes both Lennon’s admission to Pete Shotton and Peter Brown’s version (Brian gave John a blow-job) in favor of Yoko’s version (nothing happened). But if nothing happened, why do you beat up Bob Wooler? And if you’re swinging at Bob Wooler over nothing, doesn’t that make you the kind of dude who, jazzed on speed, might coldcock your best friend? It’s troubling. Here’s a quote from Lennon’s interview with Andy Peebles two days before his death:

“I mean the Beatles first national coverage was me beating up Bob Wooller, at Paul’s 21st party because he intimated I was homosexual. I must have had a fear that maybe I was homosexual to attack him like that and it’s very complicated reasoning. But I was very drunk and I hit him and I could have really killed somebody then. And that scared me.”

Were John and Stu lovers?

“Well, are we?” “Let’s not say.”

The question I keep expecting Norman to pose is this: were John and Stu lovers? As with the trip to Spain, it wouldn’t really change what we know about the people involved, but would explain the intensity of the emotions in a simple, human way. As long as biographers hide behind the “extraordinary man” tactic — stories of sentiment and showbiz — we’ll never get a proper understanding of their subjects. Violent or pacifist, straight gay or bi, the important thing about John Lennon was/is the music he made. Period. Thirty years on, it’s not too much to ask for a minimum of squeamishness. Gimme some truth!

John Lennon’s life was exhaustively chronicled, not least by himself, and this profusion of source material gives us average folks an opportunity to pierce the veil of celebrity in a rare, maybe even unique, way. That the fellow himself professed a love of truth and hatred for cant always makes me cringe extra hard when sentimentality creeps into his life story. I guess that’s my big bone to pick with the Estate: the ballad of John and Yoko is nothing if not sentimental, and both John and Yoko do not seem like sentimental people to me. They seem primarily smart, which makes me suspect that sentimentality is in there to fool the rubes. And that turns Lennon’s life from an object lesson on flawed greatness, into a dehumanizing exercise in 21st Century branding. He deserves better, and so do we.

UPDATE, the next morning: but of course John didn’t have to have kicked Stu to feel responsible for his head injury. Without John, Stu wouldn’t have even been playing with the band, in a position to get beaten up. I’ve never read a Lennon quote saying that he felt responsible, but it wouldn’t be all that surprising if he did.

Another thought-provoking post, Mike. It’s fascinating that Goldman’s and Norman’s bios get the facts almost the same — interpretation is nearly all. While I also prefer Norman’s sympathy toward John to Goldman’s animosity toward him, I can hardly stand to read Norman because of his animosity towards Paul. I think Norman’s McCartney-bashing goes beyond the John-was-the-genius-in-the-band commonplaces to a level that’s rather scary, the way Goldman’s treatment of John is scary: it makes me feel as if there’s some deep psychological reason why Norman needs Paul to have so few redeeming qualities.

I’m very tired (along with many other fans, I suspect) of the John v. Paul cage match that gets ritualistically reenacted in so many books about the group. More and more it seems to me an evasion of the really interesting questions about them as human beings and artists — especially an evasion of why they were able to create such timeless music together. Even as solo artists in the early 70s, some of their most powerful songs (“Too Many People,” “How Do You Sleep,” “Dear Friend,” “Let Me Roll It”) were in part directed at each other. Why that is — what they did for each other artistically — that’s the real question, to my mind.

As for the question of whether John attacked Stu, that seems frustratingly in the category of things we’re just not going to know for sure. I have no trouble believing that Paul doesn’t remember — I think of all the things in my own life that I can’t swear to — and that in general neither he nor anyone else close to John wants either to go on record saying something happened they aren’t sure did happen, or to believe that John could have done it.

I think the main reason the Beatles story is so fascinating is that it throws into high relief issues of understanding and interpretation that we all wrestle with. How can someone be both deeply compassionate and violent? How can people create lasting art and behave selfishly and irresponsibly? How can people be close friends and get to the point of trying to destroy each other? The level of their artistic achievements takes all this to an epic scope.

This comment has been removed by the author.

(I just deleted a test comment, to make sure it was working again.)

And back at ya, Nancy. Norman’s lack of charity towards McCartney is like a really irritating car alarm you simply tune out after a while. Critics love Lennon because he’s endlessly interesting; or perhaps because he’s the kind of rockstar they flatter themselves they’d be. But that’s separate from a cleareyed look at the music, or the man.

What made Lennon such good copy was a combination of political trendiness, desire to manipulate while being manipulated, and not knowing who the heck he was as a person. Someone who can call himself a working class hero while living in Tittenhurst–yes, it’s good copy, but it’s breathtaking self-deception and narcissism, and there’s no doubt that if Paul did it, he would’ve been filleted.

The moment that Lennon tried to checkmate Paul with the whole “I’m a genius and genius is pain and none of you can possibly understand me” stance, his eventual creative shutdown was assured, because he was isolating himself from everybody but Yoko. No marriage, no matter how wond’rous, is a substitute for the entire world. I deal with this a bit in this Beatle noir book that’s coming out in October.

“What they did for each other”

I have a theory–which you may have read on the site, I’m sure I’ve aired it here–that The Beatles’ spotty solo careers were in part caused by developing as musicians with each other. As long as they were together, they were four pieces of a perfectly complementary whole; but the moment they had to do everything themselves, their flaws showed. But they’d been so successful as a group that their egos would not let them acknowledge it–at least not before 1980.

But you’re totally right: whenever they interacted with each other, as collaborators or even as subjects, the product was much higher-quality. Lots of George’s ATMP are songs written within the corona of Beatledom. Ringo’s solo stuff can be divided into generally listenable Beatle-related stuff and everything else. Then there’s John and Paul, with the songs you mentioned, plus others. And remember that one of the rationales Lennon gave for his resurrection in ’80 was liking McCartney’s recent stuff.

This ability to goad each other makes me think they would’ve reformed eventually, simply because as the years passed, their egos shrank, and their fanbase mellowed, the music would’ve begun to outweigh all the nonsense.

What they did for each other was complete each other, musically; and as the years passed and their lives filled out, I suspect that the pleasure of playing together–in private, on their own terms–would’ve won the day.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Mike, I’d really love to believe that the Beatles could have reformed on their own terms, at some point — if anything could have healed the deep wounds they all suffered from the breakup, I think that could have done it. When I listen to “Double Fantasy” I think it was about to be possible, since John sounds happy and settled in a way that might have allowed him to reach out again.

I absolutely concur with you about John’s artistic shutdown in the mid 70s. Whenever I hear “I believe in Yoko and me / And that’s reality,” I feel appalled. The hermetic quality of that, the apparent belief that by sealing himself up with one other person he can achieve peace — it’s sad and scary. It’s no wonder he and Yoko separated for a year and a half, given that weight of need and expectation.

Nancy, in addition to the whole Beatlemania affadavit, there’s the stuff that Jack Douglas said (I just found an old interview from Beatlefan that I’ll post).

There’s simply no question in my mind that the four of them would’ve gotten together again eventually if John had wanted it to happen…And if he and Paul had been writing together, we would’ve been 85% there.

The circumstances of John and Yoko’s separation are hotly debated, among the few geeks who still care about such things. What can be said for sure was that both of them were very strong-willed people who multiplied the normal pressures of marriage and celebrity by attempting to embody something publicly perfect. That had to be a terrible strain on both of them. I don’t think we’ll ever know the true texture of their relationship; the only reason it could conceivably be any of our business is how publicly they set the rules of their marriage. Who John and Yoko were to each other, precisely, and how that changed over time, is only germane because it was so much an issue in their work and public personae.

But I hope it worked all right for them–some days I think it did, some days I think it didn’t. My bottom line with all this stuff, whether it’s John’s behavior with Stu, or Yoko’s behavior with whomever, is that we can’t know what it’s like to live like they had to live, and for stuff we can’t definitively prove one way or the other, we should show them a little rachmanus, to use a Brucian bit of Yiddish.

This is brilliant stuff, Mike. Very moving and precise, as usual. And you always ask the question(s) that we didn’t realize so badly needed asking until you ask it.

You should write a book. Oh, wait, you have — “Beatle Noir”! I’m almost done. Anyone who likes Michael’s Hey Dullblog writings will want, nay need to see this work of dark and delightful confabulation.

Devin, that means an awful lot coming from you! I’m so glad you’re enjoying it. I’m just beginning to design the bookblock today.

“Beatle Noir” is just my shorthand for the project–literally what it turned into, after three years of working on the MS–but the formal title is “Life After Death for Beginners.” I’ll let people know when the book’s available, and if enough people are interested, I might print up a special secret edition for Friends o’ Dullblog.

Ok, I’m a little late to this discussion, but I just recently discovered your blog. Wow. What a great read… thanks!

I think it’s going to take a while to have a truly non-romanticized biography of any of the boys, especially John, since there is still so much first-hand affection out there for them. Maybe 50 years from now, when authors are not Beatle contemporaries, we may see something written about them that is truly scholarly and lacks the same trite, mythological perspectives… or maybe Lewisohn will take care of that, who knows?

You have brought up so many profound points, and I’d like to address just a couple of them. Firstly, I would argue that John was indeed sentimental. Yes, he was calculating and manipulative with the press. Yes, he sold us the John/Yoko fairy tale semi-convincingly until that sad December day. And yes, he was a very spiteful person… but he was also quite nostalgic and very wistful. Too much so. He was completely absorbed in his past… and, although that sort of obsession doesn’t necessarily make one sentimental, John did have a genuine need to re-visit and re-work his own story. I think that sentiment is part of what kept him so paralyzed for most of the last years of his life.

To your point of Norman promoting many of The Estate talking points and therefore participating in an “exercise of 21st century branding,” one thing that I found interesting in John Lennon: The Life was that Norman seemed to be serving two different editors: Yoko Ono and Julia Baird. While on the one hand glossily promoting the ever-familiar Ballad of John and Yoko, he also overstated Julia’s point about how Lennon’s childhood wasn’t as horrible as John liked to make it out to be. Norman painted a picture of a sensitive child surrounded by loving relatives, but he failed to discuss in any meaningful way the deep-seated sadness and feelings of guilt, shame, confusion, and abandonment that ignited what you accurately described as Lennon’s “fierce desire to prove, achieve, outrun, defeat.” I would imagine that The Estate (aka Yoko) would take issue with Julia’s seemingly rosy view of things, since it deprives the Lennon legend of much of its artistic romanticism. (If that is indeed what The Estate is attempting to brand.)

I liked the fact that Norman left us to draw our own conclusions about Stu, since, frankly, the matter is rather nebulous. How is it to be proved now? Paul? I don’t think so… There are many people out there who argue that even if John did kick Stu in the head (which he very probably did), that assault was not responsible for Sutcliffe’s subsequent death. Apparently, their assiduous research shows that a kick in the head is superfluous to Stu’s fatal pathology. He would have died young had John and/or those other Liverpool ruffians assaulted him or not. But I’m not a doctor, so I don’t know if that is actually correct… all that matters, as you have pointed out, is that John was probably haunted with the possibility that Stu’s blood was on his hands.

Looking forward to reading more of your musings.

And backatcha, Anon. Got a whole novel’s worth of musings getting ready for the Kindle. My character isn’t Lennon, exactly, but he’s close enough to scratch this kind of itch.

Point extremely well taken about John Lennon’s sentimental nature. And his need to revisit/rework his past is precisely why I think The Beatles would’ve reformed, in some way, at some time, had Lennon not died. In fact, I think that was a lot closer to happening than we suspect.

The fascinating thing about Stu’s death is how it surely must’ve fit into Lennon’s psyche–his mother, then Stu, then Brian Epstein. The amount of psychological damage inflicted by those three losses, all within ten years or so, explains a lot of where Lennon was at circa late 1967; and that explains everything that happened after.

I’m really hopeful for Lewisohn. And it’s such a shame that we can’t have a truly forensic biography AND affection for the guys. The latter should stoke the former, IMHO.

Come back–write more!

I’m not as great a writer as any of the great people commenting here, but I think that Paul mentions that John was always kind and compassionate unless he was on something. Coming off of certain drugs and being on drink definitely made John another person.

And even though I think speculating about John and Yoko’s break up for sometime is somewhat a wast of time, I think it had a great deal to do with how disgustingly co-dependent they were with one another. There isn’t any reason to hang out with your husband or wife twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

Right on, BP. Nobody who’s familiar with the literature on addiction and codependence can fail to see how it worked in Lennon’s life. Personally, I think it’s a key to understanding him.

Your writin’ is fine. Come back soon!

[…] in the process of answering a comment from stalwart commenter Nancy, I stumbled across this excerpted Beatlefan interview with Jack […]