- In Defence of Revolver - October 21, 2019

About a month ago Michael Gerber posted an essay that argued with disconcerting eloquence and insight that Sgt. Pepper is objectively better than my all-time favourite record, Revolver. I feel compelled to respond with a few words about the album I’m sworn to defend. If you haven’t read Mike’s excellent piece already please do so now—I’ll wait.

My first quibble is with the idea that Lennon’s opinion on Pepper influenced anyone else’s. People have looked to John for wisdom, inspiration and spiritual guidance, but I don’t think they’ve ever let him tell them what Beatles songs to like. After all the chief Beatle never called Revolver one of his favourites; that honour variously went to White and MMT.

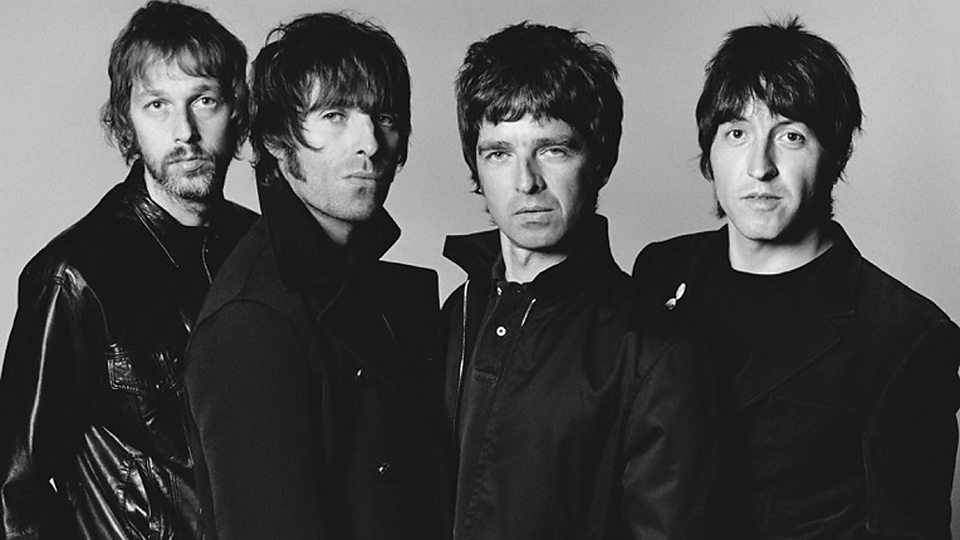

I’m more inclined to agree with Robert Rodriguez that Revolver’s stock started rising in 1990s America when Americans finally heard it: once the CD edition standardised the original version of the album fans finally got the chance to hear the band’s bold step forward in all its boldness. And in the Beatles’ homeland the Blurs and Oases (that’s the plural, right?) took their cues from the jagged pop of 1966, not Pepper.

In its time the album influenced artists from Hendrix to the Velvet Underground to Donovan and, as the first fully adult-sounding Beatles record, notified the band’s millions of imitators that the old words over the old chords with the old vocal intonations weren’t going to cut it any longer. (As Dylan famously put it, ‘I get it, you don’t want to be cute any more.’) In a nutshell, Revolver influenced bands indirectly by encouraging them to do their own thing, whereas Pepper inspired bands to make records that sounded like Pepper. Today those roles have been reversed: millions of bands take their cues from Pepper’s studio-as-instrument aesthetic…and end up making records that sound like Revolver.

But if I’ve understood you right Michael, the crux of your argument is that Pepper encapsulates its era better than Revolver or any other album: the latter was a collection of music, the former an event; the one a work of art, the other a movement. To the extent that the Beatles’ psychedelic masterpiece sounds dated that’s our era’s fault and not the record’s; it embodied the hopes of a society that dared to dream bigger than we do. This is an interesting defence because it turns one of the arguments most frequently levelled against Pepper—that it’s a time capsule where Revolver and Abbey Road are timeless—on its head. The implication is that you judge music according to how precisely it evokes its context rather than how successfully it transcends it.

This suggests sociology to me more than aesthetics, and with art I’ve always been more of an aesthetics guy. I love Caravaggio’s work for its insight into the basics of the human condition more than its evocation of the Baroque period; I love Waiting for Godot for its naked existentialism more than its embodiment of postwar angst. The historical contexts of these treasures are illuminating, but I don’t think a detailed knowledge of them is any more necessary than an immersion in historical-critical scholarship was to the spiritual lives of mediaeval peasants. Closer to home, I wholeheartedly agree with the modern critical consensus that says the ignored-upon-release Velvet Underground and Nico is an ageless masterpiece and possibly the most influential album of all time.

We agree that Revolver has better songs than Pepper, and so I see no reason why it shouldn’t be the VU and Nico to Pepper’s Are You Experienced?—something that didn’t quite revolutionise its times but has gone on to revolutionise other times. The melodies soar higher than Pepper’s, the words cut deeper (I forget who called “Eleanor Rigby” and “For No One” novellas but it’s bang on) and the emotions range wider: ebullience, awe, terror, aggression, confusion, tenderness, playfulness, mysticism. Pepper has traces of all of these, but somehow refuses to engage with them: the varieties of mood and theme are smoothed out by the overall pleasantness of the sound, so that it feels more like a single short story than a collection of short stories.

But I don’t want to attack a straw man here, and I think your historical defence of Pepper and not Supper at Emmaus or Godot depends on its being made in that time and place. You’re arguing that ‘60s hippie society wasn’t the same as Baroque or postwar culture, but a new kind of human organisation that was cut down in its prime and represents a road tragically not taken. This takes things beyond even sociology into the realm of morality: if you’re sympathetic to the aims of the ‘60s counterculture Pepper will be among your favourite albums, and if you’re not it won’t.

I don’t have much of a problem with this, being significantly more hippie-friendly than your average 29-year-old. (I think the 2010s are closer in spirit to the ‘60s than any of the intervening decades and it’s just blind allegiance to boring punk anachronisms that stops millennials seeing it.) But I do wonder where your analysis leaves people who imagine a different utopia to the psychedelic kids, or don’t like how the kids went about building their utopia, or sympathise with it in principle but don’t see it working in practice, or don’t believe a utopia’s possible, or only think it’s possible in the next life, or or. I could imagine a post on a Christian blog arguing that Dylan’s Saved is the best album of all time, because while Blonde on Blonde has better music Saved has more to say about the meaning of life.

I’m not being flippant here, just illustrating a problem I see with any analysis of art that relies on criteria beyond the immediate aesthetic value of the art itself. And while it’s true that Pepper had an impact on the world as a whole that Saved didn’t, it’s equally true that it’s routinely been rated below Revolver for about as long as I’ve been alive. None of us know what the future holds—whether Pepper’s brand of “psychedelic utopianism” will be tried again, or people will attempt to reach a different kind of utopia a different way, or the majority will just accept capitalist materialism forever. But I think that our species will ultimately decide that Revolver digs deeper into what it’s like to be human than Pepper, and keep it at the top of the canon where it belongs.

Excellent post, @Justin, and I have a few thoughts on it. I am closing the window against the fierce Santa Ana Winds, cracking open a Belhaven Black Stout, and holding forth.

.

“My first quibble is with the idea that Lennon’s opinion on Pepper influenced anyone else’s.”

.

Quibble if you must, but in the wake of Lennon’s murder, Beatle fans took his pronouncements as Holy Writ, and none more so that Pepper was the beginning of Paul’s Reign of Terror & Cuteness. Everybody felt so fucking bad, we were so guilty that a crazy fan had shot him, and all missed John so much that we were like, “Well, if JOHN said it…”

.

Really, it was like that.

.

So when John was quoted calling Pepper “the biggest load of shit we’ve ever done” — just wrap your head around that; not “a so-so album” or “not one of my favorites” but “the biggest load of shit we’ve ever done” — that had a powerful impact. Especially on critics. And it still happens; in researching this response, I found two reappraisals of Pepper that call it “a decent record and a bad thing” (Irish Times) and “The Beatles’ worst album” (LA Times).

.

What the hell? Nobody says that about Revolver. Why? Because it’s merely an LP of great songs. it doesn’t challenge the conventional conception of what a rock album is, and what rock musicians do. That doesn’t reduce the quality of the songs on Revolver, but it does show that it is fundamentally less ambitious, and less challenging, than Pepper. Critics are STILL challenged by it.

.

“that honour variously went to White and MMT.”

.

Could you link to these statements in the post? If it’s convenient. I’m always interested in pro-MMT sentiments. 🙂

.

“fans finally got the chance to hear the band’s bold step forward in all its boldness”

.

My favorite LP when I was growing up was…”Yesterday and Today.”

.

“And in the Beatles’ homeland the Blurs and Oases (that’s the plural, right?) took their cues from the jagged pop of 1966, not Pepper.”

.

I would state this a bit differently: that Revolver’s perfected power pop was more influential than Pepper’s vaudevillian psychedelia. That’s unquestionably true, but I think it makes Pepper even more singular. To do Pepper, and not something fundamentally cheesy like Odyssey and Oracle, or buttcheek-clenchingly twee like The Village Green Preservation Society, you need to have incredible musicality AND ability to connect. Ray Davies and Brian Wilson could do the musicality, but neither had the one-two punch of Lennon/McCartney; and Dylan could connect, but he was never quite as musical as McCartney and the Abbey Road helpers.

.

Revolver is, for all its excellence, a goal other musicians could perceive, and attain. Pepper hasn’t been. That’s why “millions of bands take their cues from Pepper’s studio-as-instrument aesthetic…and end up making records that sound like Revolver.” Revolver is the absolute apotheosis of guitar-driven pop; Pepper is…something unique. The closest thing is, i guess, something like Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon,” but DSotM doesn’t have Pepper’s historical resonance. To my ear, DSotM is four rockstars bitching about the alienation of being rockstars. Then they went on to bitch about the alienation of being English. How unpleasant that must be for you, Roger, but remind me why I should give a shit? 🙂

.

“The implication is that you judge music according to how precisely it evokes its context rather than how successfully it transcends it.”

.

Or that embodying one’s era–if you do it as shatteringly well as Pepper did–cannot possibly be an artistic demerit. Just as Guernica is about its time and place, and Nude Descending a Staircase, sorta isn’t. Something that embodies an era will not age as effortlessly as beautifully crafted stuff that doesn’t resonate with its time. But the craft-alone stuff will not reach a certain height; is “Eleanor Rigby” really that much better than “Waterloo Sunset”? “Here There and Everywhere” better than “God Only Knows”? “A Day in the Life” is better than all of them.

.

“Closer to home, I wholeheartedly agree with the modern critical consensus that says the ignored-upon-release Velvet Underground and Nico is an ageless masterpiece and possibly the most influential album of all time.”

.

I disagree with this so vehemently that I’m having trouble focusing my eyes. So “everybody who bought the album formed a band”—so fucking what? There are a couple of reasons for this, and none of them have anything to do with quality; in fact the reverse. Compared to Revolver or Pepper, VU’s early sound is something you can emulate pretty easily; same for Lou Reed’s affectless vocals. It’s similar to the Sex Pistols: they were so influential because almost anybody could mimic their simple sound well enough to pack a pub.

(I’m re-listening to The Velvets’ first album as I revise this and…jesus.

Sunday Morning: Lou’s flat as shit, and off-key several places. “Guys, we gotta pick the lowest-energy song to start the album.” It’s like a demo rejected by the Lovin’ Spoonful.

“Waitin’ For the Man” — GREAT. Awesome. Excellent.

“Femme Fatale”? Really? Anybody who likes Femme Fatale immediately loses all ability to make fun of Ringo songs. Listen, if you like Femme Fatale, let me introduce you to about sixty Astrid Gilberto albums that are both better sung and better written songs. Femme Fatale is music for clons.

“Venus in Furs” — Great, I like it, bullshitty suburban use of S&M but OK. Sonically: The Doors did it better. This song is The Velvets in a nutshell: it feels much more daring than it is, but that’s Warhol’s art, too; stuff that titillating to a sheltered Catholic boy from Pittsburgh.

“Run Run Run” — Sure. Perfect for “Nuggets.” About two minutes too long.

“All Tomorrow’s Parties” — Neat, in a sort of lumbering way. I like the piano. I think this would be a good record to eat brunch to, for some reason.

“Heroin” — Well, I’ll say this: if I ever wanted to shoot junk, I don’t now.

“There She Goes Again” — once again, Nuggets. Sure. Whatever guys.

“I’ll Be Your Mirror” — A bit of nothing.

“Black Angel” — please stop with the violin. Please. Stop.

“European Son” — Really: people are not listening to this for pleasure. Eventually the world got shittier, so it sounded ahead of its time, but really it was just that music got worse, Eno.

Final verdict: If The Beatles had all been ten years younger, this album is what they would’ve played in Hamburg. And moved on from.)

.

ANYWAY, in the context of other music of its time, I find VU utterly boring; I’ve heard to “Waiting for the Man” a zillion times, and the whole album, three times. (Now four.) My wife says she’s never listened to it all the way through. Nico’s stuff is embarrassing; she was added by Warhol to improve the look of the band, and sounds it. The Velvets are a critic’s band, always have been, and that’s a demerit if you believe rock to be a popular art, which I do. You can’t simultaneously rail on Pepper for making rock pretentious and ALSO praise stuff like this. Whatever flaws Pepper has, this has x1000.

.

But let’s set aside my own tastes for a second. If VU&N is “the most influential album of all time,” that explains rock’s descent from the unquestioned vanguard of popular culture (as it was with Pepper) to its current status as an ever-weakening offshoot of the fashion industry. The Velvets were the Monkees of the downtown art scene.

.

OK, that’s unfair. Let’s be fair and say that The Velvets, like Pepper, epitomized a certain scene, a time and place. Unfortunately, it was the horrific, people-eating Silver Factory, where Warhol took in strays, fed them speed, got them naked and turned cameras on them and when he was done, left them to die. Fred Herko. Edie Sedgwick. That scene, the speed and smack and S&M-and-crossdressing voyeuristic bullshit, ended when Andy tortured the wrong person in 1968. That’s the backstory to The Velvet Underground and it counts. It explains. It’s the soil from which that album blooms.

.

“so that it feels more like a single short story than a collection of short stories.”

.

Could this not be a virtue of Pepper? Why is this unity a demerit? Especially since LPs before Pepper were all a collection of short stories?

.

“if you’re sympathetic to the aims of the ‘60s counterculture Pepper will be among your favourite albums, and if you’re not it won’t.”

.

Correct. But the counterculture was many things, and changed over time. Pepper was one specific offshoot of the scene at a certain time. I think it was a particularly interesting and benign and intelligent offshoot. If you believe in the critique of the psychedelic people by Warhol and people like him (the speedfreaks in ’65 to ’67; the Yippies in ’68; the punks; etc), you’ll dismiss it as “soft-headed” “unrealistic” etc. But nobody ever looks at the endpoint of Warhol’s competing vision, which was trash. Nobody ever looks at punk and says, “How unrealistic” or the Yippies or Weather Underground and say, “How was that ever going to work?” Because pessimism and self-destruction and death is more interesting to young people, and broken older people like Warhol. In reality, there’s nothing more banal and common than self-destruction.

.

Here’s what I’m getting at: if you hang the failure of pot and LSD to bring Utopia on Pepper, you also have to acknowledge what the Velvets and that whole downtown scene was aiming for: nothing. Hustling your body for a spike. Death. The wasting of youth because you are BORED. Speed — the drug of blitzkrieg and the Mansons — was the lifeblood of the Factory. You don’t GET the VU without speedballs, and I’m just not interested in that. It’s a dead-end. Smart people knew that even in 1966.

.

“a problem I see with any analysis of art that relies on criteria beyond the immediate aesthetic value of the art itself.”

.

Aesthetics according to who, though? To me, that boils down to “it’s good because it sounds good to me,” which is…ok? But doesn’t lead to much discussion.

.

Criticism that is fundamentally historical and moral has facts in it that can be identified and debated; Valerie Solanis did shoot Warhol; Lou Reed did call him “Drella,” a combined of Cinderella and Dracula, because he used people like a vampire; Edie Sedgwick was a tragedy.

.

Where’s the drama, the wreckage, around Revolver? Or Pepper? There isn’t any. And that’s on purpose. The world around the Beatles was just as X-rated as anything the Velvets were going through (remember the story about the beautiful girl trying to hook Paul on heroin in 1965?), but J/P/G/R chose to transmute that experience, not wallow in it for a cheap thrill. I like Revolver’s milieu, the optimistic switched-on “Blow-Up” London of 1966, almost as much as Pepper’s. I love Revolver, because like Pepper, it’s a great place to be. I just find Pepper a little more unified, a little more inventive, a little more interesting.

.

And now I’ve finished my beer and have to go back to finishing Bystander #13. Thank you again for a wonderful post! And screw Lou Reed, who used to live next door to me in the Village. I’m sure he was a nice guy, but his music launched a thousand assholes.

Going to stay in the shallow end here, but it strikes me that part of the reason Pepper is polarizing is that in it the Beatles take on an alternate identity — no doubt one of the reasons John hated it. I think that kind of flexibility and refusal to stay with one identity has had a significant influence on some later bands. Releasing albums incognito, forming a secondary band, having side projects that go off on tangents; all those existed before Pepper, but Pepper was such a huge success that it made that sort of flexing clearly possible, IMO.

.

In the end, I love Pepper and I love Revolver. But to me Pepper has more magic in it.

.

Michael, you and I may have to have a throw down about “Village Green”! I think Davies is bringing more salt to the party than you give him credit for. Also, I mostly agree about VU being a critic’s band. I love “Sweet Jane,” “Waiting for the Man,” and “Satellite of Love” (solo LR, I know), and that’s kind of it. I had a friend who was really into Nico and it just wouldn’t take for me. Rather like a guy I dated who really tried to get me into Yngwie Malmsteen and Joe Satriani. No dice.

Not really serious about “Village Green.” More making the point that all the shit people talk about McCartney and Pepper — “it isn’t rock! It’s vaudeville! blah blah blah” — goes DOUBLE for Village Green and Arthur and suchlike. *I* personally don’t mind it. But there’s a double-standard critics apply; they often lionize things like Odyssey and Oracle, or Village Green Preservation Society, merely because their conception of the zeitgeist suggests that they are *discovering* it for someone.

.

Pepper was doomed, in those people’s eyes, because it wasn’t a failure. If it had been a failure — not even an artistic failure, just something like SMiLE — it would be as big or bigger a part of the Beatles’ legend than it is. Excellence bores the critic. There is nothing to say, no purchase on the object.

.

Don’t get me wrong about Nico: “La Dolce Vita” is probably my all-time favorite movie, and she’s great in it. And I don’t even really MIND her as a singer. But her presence on that album isn’t neutral.

.

I had a high school friend who pronounced Yngwie as “G’NEW-ie.”

I wish there was a like button for this .:)

Are you encouraging Justin (you should) or telling me I should drunk-comment more often? 🙂

[…] In Defence of Revolver October 21, 2019 […]

Sorry I thought I hit the reply button for your comment. But I’m encouraging your drunk commenting I guess. 😀

And Justin as well, because after all, that’s what inspired your comment, can’t have the comment without the original post!

Mike, the cold weather’s making you MEAN! Poor Mr. Reed! 😉 OK, this is gonna be fun. Here goes.

.

The Donald Clarke piece you linked to is boilerplate punk reverse snobbery (he’s the Irish Times’ *film* critic by the way, and it shows). Exactly the kind of reactionary-but-thinks-it’s-the-opposite-of-reactionary old hat I was complaining about in my post: ever since it came in 40 – 40! – years ago it’s exerted a stranglehold over rock criticism, all while congratulating itself on how enlightened it is for dissing “dadrock”. All the three-chords-and-the-truth brigade can congratulate themselves on is ensuring rock would run itself into the ground well before the end of the twentieth century. Just everything that’s wrong.

.

I wasn’t around when John was killed, but I suspect this ‘Don’t you DARE improve on Chuck Berry!’ mindset – which had always been lurking in Christgau, Bangs and Cohn’s stuff and became orthodoxy once the Sex Pistols hit – had more to do with Pepper’s fall than anything else. (I’ve added links to Lennon’s opinions on White and MMT by the way.) And I agree that the punk purists are throwing the baby out with the bathwater – but you know what, I found myself agreeing with a surprising amount of the LA Times article.

.

The “Day in the Life” putdown is ridiculous – what does he find ‘truly radical’ on White, “Revolution #9?” – but I’m with him on the rest: the Beatles ARE heavier, prettier, more intense and more invigorating on other albums than on Pepper. And they DO try to do a bit of everything on Pepper rather than a lot of anything. That’s what I mean when I say the album’s too unified: there are a variety of musical elements, but they all serve more or less the same mood – a mood which isn’t extreme enough to be satisfying for 35 minutes – until the closing track finally breaks the monotony.

.

I agree with this part of the article so much I have to quote it whole: ‘[Its] achievements belong to the past; the valuable work “Sgt. Pepper” did in reflecting its time and broadening rock’s scope has already been done (and roundly commended, to say the least). What we’re left to reckon with a half-century later is the music itself — what it has to offer listeners shaped by the album’s advances as well as by all those that followed.’

.

Given my criticisms of the music above, I don’t think critics are *challenged* by Pepper so much as just annoyed that an album whose cultural work is done continues to receive such high praise out of proportion to the quality of what we’re hearing. If something’s constantly being overrated it’s natural to want to tear it down; isn’t this what you’re doing with VU & Nico, Village Green, Odyssey and Oracle and Dark Side of the Moon (all of which I and millions of others love)?

.

If we were to take the “historical importance” approach to shaping a canon, you could argue that Please Please Me is the Beatles’ best album. Aesthetically, it’s their worst because it’s underdeveloped and it has “Ask Me Why” on it. But in terms of breaking down barriers, empowering other bands, loosening up the culture and ushering in the whole thing we call the ‘60s, it did even more than Pepper. Or go back to the ‘50s rock ‘n’ rollers – they rewrote the cultural map in every way possible, even helping invent the very concept of teenagerhood. But their actual songs are period pieces one and all.

.

Or to make another comparison that’s seriously gonna hurt (look at the sacrifices I make for my art!) – take Bob Dylan, the man who’s written more great songs than perhaps anyone in history. Now I love him to death, but I have to admit that his clout is shrinking by the decade and his music and lyrics have next to no impact on modern pop.

.

But what amazes me every time I read about the music of the ‘60s is that the man was EVERYWHERE – every band was influenced by him, fans venerated him, lyricists imitated him, poets were threatened by him, half the vocalists copied him, all the critics looked up to him, entire scenes rose and fell because of him. Point to virtually any current of American music from 1965 to 1970 and Dylan was at least as responsible for it as the Beatles. (American psychedelia owed its roots to folk and country every bit as much as “roots” music did.) Just about all the cool cats agreed that the man made the smartest, most incisive, hippest music going.

.

What no-one at the time could have known is that Dylan’s genius was so intensely in tune with the forces that shaped the Sixties that it couldn’t fully survive their death. As soon as the times had changed, his cultural work was done and he was doomed to become forever less relevant, sticking to his favourite blues and folk templates while the kids went the way of the dancefloor. That’s what happens when your stock in trade is meaning and depth and the world decides overnight that it doesn’t care about them any more.

.

Here’s the thing though: people like me who do care about Dylan more or less agree that his best albums are Blonde on Blonde and Blood on the Tracks. But those albums don’t contain any of his most historically or socially important songs: those are all on Freewheelin’ and Times They Are A-Changin’. At the time, “Blowin’ in the Wind”, “Masters of War” and “Hard Rain” were immensely powerful anthems that galvanised an entire counterculture and expressed its hopes and dreams, but today most people haven’t even heard of ⅔ of them. Intensely moving as the March on Washington footage is, now that the event’s passing into history you won’t find many listeners who prefer “Only a Pawn in Their Game” to “Just Like a Woman”.

.

That’s why I separate historical resonance so sharply from aesthetics. No matter how much I’d like people to prefer Dylan to Pink Floyd, the fact remains that only connoisseurs play Freewheelin’ any more and everyone plays DSOTM. The first is a fascinating window into a time and place, but the latter refuses to grow old. To you it may be about rockstars bitching, but to the vast majority of classic rock fans – including me – it’s a gloriously pessimistic meditation on time, fate, madness, Britishness, death, everything. It’s stood the test of time better than Pepper because it evokes the human experience in general rather than a rapidly fading historical period in particular.

.

I get three more points of view from your comment that I’d like to challenge – firstly that a song’s literal meaning is all there is to the song, secondly that a song’s tainted by the environment that created it, and thirdly that music should always be uplifting.

.

(1) To me it doesn’t really matter that the subject matter of “Venus in Furs” isn’t shocking any more or that “Heroin” is about, well, heroin; I listen to the one and think ‘That’s the most gothic soundscape I’ve ever heard! Who but this band can make me feel like I’m touring a mediaeval castle with a mocking Brooklynite?’ and listen to the other and think ‘This is nothing less than naked alienation in musical form: the jangling viola, dissonance and strung-out vocals are absolutely chilling’. “Heroin” in particular gets right under the skin of isolation, jadedness and pain – you learn about a particular facet of the human experience from it every bit as much as you do from reading great literature or watching Trainspotting. Your understanding of human nature is broadened.

.

(2) Does the backstory to the VU really count? Do we deny the human impact of Caravaggio’s paintings because he was a murderer, or throw out Rimbaud because he sold arms and possibly slaves? Again, I think the more historical distance you get from the context of a work of art – including the lifestyle of the artist – the more clearly you can see the artwork for what it is. The VU experienced some pretty dark stuff and made art from it that can enrich our lives without us having to live through any of it ourselves.

.

(3) Which brings me to this – I can understand why someone would want all music to be uplifting, wholesome and instructive, but I can’t live up to that ideal in my own listening life. When I need to steel myself for something I like to blast me some LCD Soundsystem, when I’m in one of those reflective moods I go for Joni Mitchell’s Blue and when I’m angry I relish the bracing punk fury of Husker Du. You can argue that gangsta rap, hardcore punk and metal do more harm than good by entrenching people in alienation, but I think it’s too much to ask that music only reflect our best impulses and moods. It’s a tough world out there, and some tough days are best met with tough music.

.

OK, your turn 🙂

OK, there’s a lot in this comment and without copious quantities of time and alcohol, neither of which are at hand, I fear I won’t be able to nearly do it justice. But here goes. I am purposely speaking intemperately, with much more emotion than I really feel, for the fun of it. Don’t take it seriously, folks.

.

The trouble with valuing aesthetics (i.e., personal musical taste) over historical relevance is that we’re expanding from a sample size of one. Over and over in your post, I kept thinking, “Everybody plays Dark Side of the Moon? Justin, I have never once owned any Pink Floyd, in any format. Which means I have never once thought, ‘Gee, I wish I could listen to DSOTM.'” But that’s me. Maybe I’m weird. Maybe I will go to YouTube and fire up Zep and Hendrix and Santana and T. Rex and Cream and…but never once Pink Floyd. Never. Once. Does that make DSOTM irrelevant? Of course not. But I could just as easily say, “Nobody plays Dark Side of the Moon,” and that would be equally valid: it’s a data point.

.

So how does Pink Floyd intersect with my life as a 50-year-old interested in classic rock living in a city which is arguably the world capitol of popular music? Well, Floyd is like Zeppelin, or Queen before the movie: a staple of classic rock radio, right along with (get ready) Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles. If you turn on a classic rock station, which is the only place that DSOTM has any contemporary cultural currency, you hear it alongside other music of the same historical era. To me this suggests strongly that, you and me aside, Floyd in general and “Dark Side” and “The Wall” in particular are primarily enjoyed within their historical era, not as freestanding statements of musical genius transcending their era. They may impact you and other readers as such, but they clearly do not impact me that way, nor it seems the rest of the culture here in Los Angeles in that way.

.

Why? Because popular music, like popular art, cycles much more quickly. Everybody here is listening to…fuck if I know! This makes aesthetics even harder to use as any kind of standard; and the only people who are going to fight through and create some kind of Personal Aesthetic upon which to make Sweeping Judgments are 1) critics and 2) musicians.

.

As we point out constantly on this site, critics and even fellow musicians are prone to the vagaries of fashion. Witness: RAM, which one could argue has been more influential than any other solo album, or even acknowledged Beat Brother classics like Pepper or Abbey Road. Does this make RAM better? Only if your criteria are the same ones you’re using with VU — which to me are crazy. Critics and musicians don’t set the canon of a popular art; the mass of fans do.

.

But this fickleness and difficulty doesn’t mean that it’s fair, proper or wise to strip a piece of popular art of its historical context when judging its place in the canon. Let me translate a quote for you. “What we’re left to reckon with a half-century later is the music itself — what it has to offer listeners shaped by the album’s advances as well as by all those that followed.’ That means, “I’m bored with, or more likely ignorant of and thus uninterested in, the history surrounding Pepper. I don’t want to talk about that. I want to take my modern ears, with all their (totally random, not better) modern preferences and judge it, and feel superior and feel my time is superior. I want to decide whether *I* like Pepper or not, based on whatever reasoning I pull out of my ass, and then tell you, the reader, how you should feel about it. Because, frankly, that’s a goddamn easy article to write, with basically nothing my editors can flag or fact-check, as opposed to something that I’m going to have to research and probably defend, because the history of the 60s is a huge hot-button here in the States. And frankly? I get paid the same regardless, and I don’t need the hassle. So: Pepper bores me. The fact that it didn’t bore people then — in fact they thought it was genius — and that it totally changed what came after? Fuck all that. I’m writing this article, and I’ve been asked to come up with ‘a new take’. So: here.”

.

What I did in the earlier reply was go through VU&Nico and demonstrate just how easy and fun it is to do this. But all you really learned from my words was that *I* don’t like the album. That it influenced a lot of bands is an historical fact; it is that album’s historical context. And because of that, I don’t have to like it, but I do have to engage with it. And if we have to engage with VU & Nico, we really have to engage with Pepper.

.

All history is, I think we can agree, is a story that has been agreed upon by many people; and this agreement is conferred because the story expresses something important about that time. There are many versions of the story; there are many histories within the larger history; but there is that basic agreement, which is where any critique based on that agreement gets its authority. Criticism based on personal taste — what you call “aesthetics” — is simply a personal assertion of authority. “I am a musician, so — ” “I am a critic, so — ” It is weaker and, to me, less interesting, because I know just how randomly determined my own tastes are, how mediated by time and place and associations. It’s not impossible that if my Aunt Mary had preferred the Rolling Stones, this site wouldn’t exist.

.

As to Dylan — just like the Beatles — it’s not quite fair to track them downward without also tracking the entire popular art downward. Part of what’s important about Pepper is that it represents a kind of apogee, a moment of unity, during which Western culture was uniquely turned towards popular music. This is indisputable. Pepper didn’t just capture the zeitgeist (though it did), it captured it pretty much at the last moment before the counterculture and the popular music that serviced it exploded into a million fragmented scenes. That’s notable. That’s at least as notable as “Lovely Rita doesn’t do it for me.”

.

In fact, rather than looking at Dylan’s diminution and saying, “Well, see, that’s why you can’t count on historical relevance to point to great art,” you could just as easily look at the period of 1963-68 and say, “For this brief time, popular music carried an historical importance that it didn’t have before or since, and that importance fed into the music making it excellent, and was fed by the excellence of it, in a feedback loop. So music that was popular then is particularly important.” You go talk to someone who was a teenager during the period of 1963-68, and they’re going to mention the importance of the music to them personally, and to the culture at large. And then go talk to someone who was a teenager ten years later, and they’re going to mention the importance of music like DSOTM in getting really fucking baked in their parents’ basement. I’m not kidding; Floyd, Zep, Queen — none of these groups had anything NEAR the cultural or political importance as Dylan or The Beatles or even the SF groups like The Dead. Does that make them not worth talking about? No; but you have to talk about them like you talk about “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” Mere pop culture. Pepper is not mere pop culture, and that was recognized from the moment it was released, and continues to be recognized. All those people could be wrong, and the LAT guy could be right…or he could be just cranking out an easy contrarian take on deadline.

.

“I get three more points of view from your comment that I’d like to challenge – firstly that a song’s literal meaning is all there is to the song, secondly that a song’s tainted by the environment that created it, and thirdly that music should always be uplifting.”

.

If you paraphrase me, you’re introducing a level of imprecision in here that’s unnecessary, but no big, I’ll work with what you wrote.

.

I would say that “a song’s literal meaning” has to be the starting point of all critique, because otherwise a single empowered listener is asserting his/her reading of a song — even more than that, how the arrangement of sounds is making them feel — to be something more than a single data point. I can listen to the music and make certain broad statements; I can read the lyrics and assume that the writer is using the standard meanings. Is that what you mean by the song’s literal meaning? Where else can one start? It’s either that or, “I really liked the guitar solo ’cause it makes me get tingly.” Or “This song makes me think about my grandma for some reason.” That’s not nothing, but it’s not really something, either.

.

(1) To me it doesn’t really matter that the subject matter of “Venus in Furs” isn’t shocking any more or that “Heroin” is about, well, heroin; I listen to the one and think ‘That’s the most gothic soundscape I’ve ever heard!”

.

In 1984, at age 15, I bought both the VU’s first album, and the 12″ of “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.” I played the former once, and the latter constantly. The Bauhaus song was what the VU tried and failed to do; that “gothic soundscape” was immensely more transporting, immensely creepier, and just more fun to listen to. Would it have existed if not for “Venus In Furs” or “Heroin”? Who knows? But by the language of my aesthetics, that Bauhaus album kicks VU’s ass even on the limited scope you defined. But it’s not really fair of me to only listen to “Venus In Furs” in the context of Bauhaus or Joy Division; it’s not really fair for me to wipe it away because the later music is more pleasing to my later ear.

.

“…you learn about a particular facet of the human experience from it every bit as much as you do from reading great literature or watching Trainspotting. Your understanding of human nature is broadened.”

.

I disagree. You’ve listened to a cool song, and then your brain makes up all sorts of interesting fantasies of what it must be like to be on junk, and what it might mean for you if you were on it, and so forth. You are not broadened, because you have not experienced; you have simply consumed some media. Consuming media is not the same as experiencing. I would argue quite vigorously that — for me — I learned one million times more what heroin is like by stepping over junkies in the doorways of Capitol Hill in Seattle in 1995. This little voyeuristic lie is at the heart of so much modern media, and it’s the secret sauce of Warholian art. But it’s not true, and once the illusion is shattered for you, it’s shattered, and you look at all that kind of thing as the sham it is. The only way to know what heroin is like is to take heroin (don’t take heroin); the only way to know what an S&M scene is like is to go do that (feel free).

.

(2) Does the backstory to the VU really count? Do we deny the human impact of Caravaggio’s paintings because he was a murderer, or throw out Rimbaud because he sold arms and possibly slaves? Again, I think the more historical distance you get from the context of a work of art – including the lifestyle of the artist – the more clearly you can see the artwork for what it is. The VU experienced some pretty dark stuff and made art from it that can enrich our lives without us having to live through any of it ourselves.

.

Let’s go through this:

Yes, the backstory counts, because it’s only through the backstory that you can approximate the author’s intent, and locate the work in its time. If that’s important to you. It’s important to me, for reasons I’ve explained.

Check back with me in 400 years to see whether Lou fucking Reed is considered to be an artist on the level of Caravaggio. I mean, no offense to my old neighbor, but jesus. Nowhere in the world is Lou Reed considered to be a major artist of the 20th Century, much less someone who will be speaking to people in four centuries. John Lennon and Paul McCartney might. Might. To assert that kind of strength to Lou Reed’s work is the wishing of a fan. Which: no judgment, here of all places.

.

(3) Which brings me to this – I can understand why someone would want all music to be uplifting, wholesome and instructive, but I can’t live up to that ideal in my own listening life.

.

I don’t feel all music has to be those things. I do think that, to the degree that popular music is about image and “shocking the bourgeoisie,” it’s an immature art of little consequence. Such outrages are too bounded by their own time — specifically narrow ideas of sin and propriety — to say much worth hearing. And I think Lou Reed, particularly in the period of 1967-74, was all about that, some great songs aside. Drug use and “exotic” sex are both as common as dirt. VU & Nico, to me, is the musings of a nice Jewish boy from Syosset desperately, painfully trying to make himself into something more interesting to himself. And speaks most strongly to people trying to do their own version of that, which is why it inspires bands/musicians. I think Pepper — even in, especially in, its uncool moments — is the mature product of mature artists, confident enough to put gritty reality (“She’s Leaving Home”) in non-gritty musical packages. Running away from home, maybe to get an abortion? That story is just as dark as anything Lou’s talking about, and a million times more real than some S&M bullshit. It’s just less titillating, and less overt.

.

When you write, “That’s what I mean when I say the album’s too unified: there are a variety of musical elements, but they all serve more or less the same mood – a mood which isn’t extreme enough to be satisfying for 35 minutes – until the closing track finally breaks the monotony” what I hear is simply this: “I’m not letting the album exist on its own terms; my modern ears want it to be something different than it is.” Who can argue with that? But I submit to you that your modern ears are letting you down. It’s not about aesthetics, not about preferences; Pepper is the essential bridge between the Old Showbiz — “Here are a collection of exquisitely crafted rock songs (Revolver)” and the New — “We, the artists, are going to take you on a journey.” The concept of “we are artists, and we are in control” is the true concept of this concept album, and once this radical idea had been demonstrated to be a commercial winner, rock and roll turned into rock, and the way opened for everyone else to walk through. I can’t prove it, but my Spidey-Sense says that the exact same decadent shit was happening around Brian Epstein and that crowd in London, as was happening in the Factory; and The Beatles took a good look at it, pivoted and made Pepper. The future was not self-conscious pop songs about stuff the in-crowd was fascinated by, shooting junk or licking someone’s boot; the future was in rock as art, with the musicians in charge of everything, and everybody — Lou Reed very much included — benefitted from that breakthrough.

.

I’m talked out on this topic, but you feel free. I’ve enjoyed it.

I have plenty more to say but I wouldn’t want to shout into a void so I’ll leave it here – look forward to having long arguments on different topics 😉

Justin, I agree with you about both Dylan and “Dark Side of the Moon.”

.

The mockumentary “Like A Mighty Wind” makes me think of Dylan, even though it has an overtly more Peter, Paul, and Mary focus.

.

I also agree with you about “tough music,” but I think historically music that’s dark has tended to get more of a critical pass, with upbeat or positive music often being seen as sentimental or escapist. And I think there’s an important distinction between “tough music” and just plain ugly and offensive music — for me, the Stones are sometimes guilty of the latter. “Midnight Rambler” is the “American Psycho” of the music world, in that it wants credit for being art while wallowing in sadism. Just my opinion, of course.

Nancy, I absolutely can’t stand “American Psycho”. (The film – after seeing it you’d have to pay me good money to read the book.) The reason I don’t like literalism in music interpretation is that the world of sound conveys infinitely more than lyrics do on paper, and that’s what makes us listen to music in the first place. Just because Beethoven’s 6th means different things to different people doesn’t mean it isn’t strongly and obviously evocative of nature, or that opinions on it amount to nothing more than personal taste.

.

So to me “Midnight Rambler” is glorious, wild, epic music even if the lyrics are distasteful, and I feel similarly about a lot of VU&Nico. Of course, if the music on those records doesn’t do it for you the lyrics won’t be saved – and the more wrongheaded lyrics are the harder it is to get past them. You may even start wondering if you *should* attempt to get past them.

.

Totally agree that tough music (and movies, and books) have been rated higher than pleasant ones for basically the entire 20th century, and while we’re kicking against the trend a bit in the 2010s it’s still alive and well. As someone who counts Village Green Preservation Society in their top 10 albums I think it’s a grave mistake to shut innocence and warmth out of your aesthetic diet. That has a distorting effect.