- Old Draft: Beatles Folk Memory 1970-1995 - December 8, 2025

- Lights are back on. - December 8, 2025

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

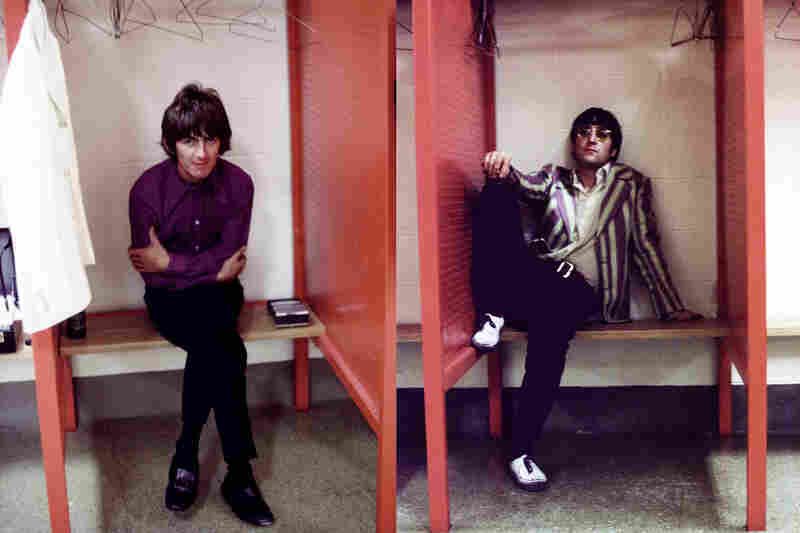

George and John boxed up backstage, Busch Stadium St. Louis, 1966.

Large chunks of the Beatle catalog are so celebrated they’ve become hard to perceive. (Try writing about “Yesterday,” for example.) So when someone comes to me with a new angle, I immediately take notice. I find Faith’s vision of Revolver and Pepper as twins to be an interesting, challenging idea. I hope you agree. –MG

The greatest of blessings come to us through madness, when it is sent as a gift of the gods.” — Socrates

A little before midnight and I’m not sleeping. The edible from an hour ago is just starting to take effect. I slip out of bed, grab the headphones and–without fully thinking this through–press play on Revolver.

I’ve listened to Revolver many, many times, of course, but never like this–alone in the deep night on the edge of sleep, isolated by noise-canceling headphones and darkness, high on some particularly potent weed, at that still point where the veil between the worlds is hairline-thin.

In other words, precisely the way Revolver was meant to be listened to.

1…2…3…4…George’s voice slithers into my ears and the ride begins,“Taxman,” all rage and razor blades. “Eleanor Rigby,” and the strings curl their fingers around my throat and threaten oblivion. Paul seduces me with his silken obsession in “Here There & Everywhere” and how can I not surrender and then “She Said, She Said” and John’s right, I feel like I’ve never been born…“Good Morning Sunshine”’s subversive mania burns my feet as I touch the ground (why do people think this is a feel-good track??) and the situation isn’t helped at all by the crazy clown piano and backwards guitar of “I Want To Tell You”… Paul’s obsession crumbles into the disillusion of “For No One” which morphs into the stalker fantasy of “Got To Get You Into My Life.” (yes, it’s about drugs, but it’s also not about drugs). Then John pulls me under again and after that, there’s no oxygen, just surrendering to the void…

By “Tomorrow Never Knows,” consensual reality is a distant memory, just something I heard somebody talk about once. Whatever remains of “me” fragments, flesh and bone sinking through the bed and the floor into the frozen ground of an icy winter night, mind and spirit rising into the expanding firmament overhead, a white-hot cord of awareness connecting the two until I’m stretched across the universe, a meteor shower of splintered glass slicing into my consciousness, a million edges bleeding me into the arms of a feral and unforgiving God.

The rest of the night passes in a fever dream, restless, agitated, stalked by visions of sharp objects and chaos, swarming roaches of energy skittering under my skin and into my skull.

The morning after is no better. I can’t get it together. I mean, I really can’t get it together, “it” being my thoughts, my sense of self, my ability to function in whatever reality this purports to be. Nothing feels solid, nothing feels like it has to happen, not even breathing. Roach-like energy from the night before still crawls along my spine and into my hands. Movement is the only thing that relieves the feeling of being trapped in an electrical field. I wander through rooms, picking up random objects and setting them down again. I pick up my guitar, try to work on a song, but my fingers can’t find even the simplest chords. Everything sounds out of tune.

In need of something to tether me, I make coffee. Surprised by the concept of “hot,” I burn myself on the kettle. The pain shocks me into the moment, and I hold my hand under the kitchen tap. The cold water rakes over my fingers like Paul’s guitar solo on “Taxman.”

I’m used to the freaky aftereffects of alternative consciousness, something I’ve explored in various forms for years. I’ve had “good” trips and “bad” trips, with and without the assist of substances, but this is extreme and uncomfortable in a new and unsettling way.

I call a friend who’s conversant in altered states. She’s on west coast time, three hours earlier, but screw it.

“I need help,” I say when she answers, grouchy and sleepy. “I think the Beatles are driving me insane.”

The reaction I’m having is precisely the reaction that Revolver was intended to provoke. It comes with a warning label, after all. Right there In the title.

Most writers focus on a vague association with revolving turntables. The story changes every time it’s told. Guns are rarely mentioned, sometimes they’re specifically not mentioned and we believe this because we want to believe it, because most of us don’t like thinking of the Beatles in relationship to guns. (There are, BTW, a striking number of photos of the Beatles with guns.). But the thing is, when we use a word, we get all of its associations, not just the ones we like. The Beatles are world-class wordsmiths, and there is exactly zero chance that in 1966, three years after the Kennedy assassination, they don’t know that in America (their biggest market) ‘revolver’ doesn’t mean turntable. They are well aware that the music they’re about to release into the wild is dangerous.

Most writers focus on a vague association with revolving turntables. The story changes every time it’s told. Guns are rarely mentioned, sometimes they’re specifically not mentioned and we believe this because we want to believe it, because most of us don’t like thinking of the Beatles in relationship to guns. (There are, BTW, a striking number of photos of the Beatles with guns.). But the thing is, when we use a word, we get all of its associations, not just the ones we like. The Beatles are world-class wordsmiths, and there is exactly zero chance that in 1966, three years after the Kennedy assassination, they don’t know that in America (their biggest market) ‘revolver’ doesn’t mean turntable. They are well aware that the music they’re about to release into the wild is dangerous.

From the start, the ‘66 tour is different. Darker, grimmer, spiked with paranoia and rage. History mostly remembers the Jesus comment, but that was just one piece of geographically-isolated shrapnel from the global detonation. Extremist protests and death threats in Japan, the Beatles under armed guard in their Tokyo hotel. International incidents and violence at the airport in the Philippines. In the American South, #TeamJesus burns records and the KKK threatens assassination. The Beatles are pelted with projectiles, including garbage, during concerts. In Cleveland, 2,000 fans break the barriers and riot. The band watches, helpless, as police bludgeon people with nightsticks, before being sequestered backstage till it’s safe to resume the show. This is the first time, but not the last, that Beatles fans get dangerously out of control. Stage invasions become the new normal. 7,000 people crash the barriers at Dodger Stadium, and again at Candlestick Park. In Memphis, Fundamentalist Christians protest outside the venue and a cherry bomb is thrown onstage. In an event only slightly less seismic, John Lennon apologizes, but not before openly weeping backstage before the press conference.

Through it all, Revolver is the soundtrack to the chaos.

We all know the ‘66 tour was like this, but we rarely talk about why. What was different this time?

Revolver is what was different.

Stay with me here. There’s precedent.

Audiences rioted at the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the music of which was described at the time as “pounding with the rhythm of engines, whirls and spirals like screws and flywheels, grinds and shrieks like laboring metal.” (Rosenfeld, Musical Portraits, 1920). Sixty years later, a New York Times reviewer described Rite of Spring as “great crunching, snarling chords from the brass and thundering thumps from the timpani.” (NYT 3/23/84) Sound familiar?

There’s more.

Schoenberg’s 1913 “Skandalkonzert” (“scandal concert”) caused riots when audiences were overwhelmed by the experimental nature of the music. The play Ubu Roi by French writer Alfred Jarry, which helped to usher in surrealism at the turn of the 19th century, also drove audiences to violence. Michelangelo’s Pieta, Picasso’s Guernica, Rembrandt’s Night Watch, all vandalized by people driven over the edge by work that was more challenging than their psyches could handle. A year after Revolver, the violent outbursts directed towards Barnett Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III will become famous enough to spawn a documentary.

This is what happens when art is too far ahead of its time, when people aren’t ready for it.

The Beatles aren’t performing cuts from Revolver in their live shows, but the album is piped in on the sound system before their concerts, stays at #1 for the duration of the tour, bleeds into people’s heads throughout that long, unusually hot summer of ‘66. Grinds and shrieks and great crunching snarling chords crawl into and out of ears, just as Klaus Voorman’s cover art presages that it will.

A lot of people go a little mad. A lot of people spend more time going a little mad than actually listening to the music. Revolver tops the charts, but it doesn’t stay there quite as long as expected, doesn’t sell quite as well as it should, despite (because of) its unprecedented, revolutionary sound.

The Beatles go a little mad, too, though for them it translates not into destruction, but into finally being so extremely done with the bullshit that they can’t take it anymore. Leaving Candlestick Park, locked away in their armored truck, even Paul decides enough is enough. When Paul McCartney is fed up with live performance, you know it’s the end times.

Even before the ‘66 Tour From Hell, madness is on the Beatles’ minds, which is how Revolver gets recorded in the first place. The chains may have come off in the studio, but the chains of being Beatles are digging hard into their skin. Having realized their wildest teenage fantasies, they’re chafing at their mop-top image and the limitations imposed by touring, creatively restless and tripping on pot and LSD, straining against the suffocating restrictions of their off-the-charts fame, and things need to change, like, yesterday.

Their first shot across the bow is “the butcher cover,” but that’s not nearly enough and anyway, they’re forced by their American label to backpedal. Their manifesto of discontent will have to be delivered through the music, of course, and it is. With a vengeance.

Revolver is all about the madness of confinement. It’s the Beatles tearing at their perfectly tailored Pierre Cardin straitjackets, scraping their bloodied fingernails over the steel walls of their armored truck after performing behind a wire barricade for 50,000 shrieking fans. It’s the Beatles, ready and willing to gnaw their feet off to escape from the trap.

You want to drive us mad? they snarl. You want to confine us? Fuck you, here’s what confinement feels like. See how you like it for a change.

Track by track, they try every escape available to them. John tries to sleep and argue his way out. George tries philosophizing. Ringo tries disappearing into an alternate universe, making the best of being trapped in an enclosed space with a bunch of lunatics (as he’ll do again on Abbey Road). Doctor Robert and his cocktail of oblivion can’t help. Neither can fame, fortune or green birds, whatever those are. Even a forced march into the blinding sunshine of the asylum’s exercise yard offers but a temporary reprieve and only results in scorched feet. And were there ever two people more trapped in the madness of confinement than Eleanor Rigby and Father McKenzie? Paul almost makes it out–for a heady moment, he thinks romantic obsession will set him free or at least offer a more comfortable kind of confinement, but love (or lust, it’s so hard to tell with Paul…) turns out to be just as claustrophobic as the cell he’s trying to escape. It’s one of those horror movie mazes where no matter what they try, they always end up back where they started. They’re The Beatles and there is no escape. No one will be saved.

By December, the Great Global Revolver Freak-Out is over. The Beatles have freed themselves from the restraints of touring, but they’re still confined — this time in the studio and this time, voluntarily. They have unfinished business with us.

They’re busy remaking Revolver.

END PART 1

Part 2…. in which this last sentence is unpacked in detail… is right here.

Meanwhile, for further reading, I recommend the book “Beatles ‘66’ by Steve Turner, as well as Hey Dullblog contributor Devin McKinney’s excellent chapter on Revolver in his book Magic Circles.

Wow. Thanks for this. I hope your friend had good advice. Was writing this article what you needed?

It *kind of* makes me want to go listen to Revolver alone, but also a little afraid.

My friend is a wisewoman, and in this case, her advice was, let it be…. I’m now more careful when I listen to anything from their psychedelic period on edibles and headphones… it’s not an experience for the faint of heart.

Thank you for reading! this one was fun to write.

This is a very interesting take and I agree with many of the points about the historical context and the Beatles’ own experiences in 1966, but I think there’s too much effort to force everything in the album to embrace the theme of confinement. For example, I don’t hear “Here, There, and Everywhere” as ultimately being about how love / lust is “just as claustrophobic as the cell he’s trying to escape.”

Thank you for the comment, Nancy. I replied to the question re: Here There and Everywhere below… feel free of course not to approve, just didn’t want to ignore you!

Faith, thank you for writing this piece — I enjoyed it and am enjoying the comments. I don’t find the album as consistently cold as some others seem to, but that may well be me.

No, I agree with you Nancy. I don’t find it cold either. But, the Beatles to me represent joy and love. I don’t find anything they’ve done cold or dark.

Well, “I Want You” (She’s so heavy) is a little scary.

Much of it is psychedelic to me and I’m sure others as well, which can be scary but not cold in my opinion. “I Want You” is scary in a good way. Another one which Nancy has mentioned before is “Blue Jay Way”. But it was “Why Don’t We Do it in the Road?” which I heard for the first time when sleeping with the radio on one night which made me jump out of bed and say, WTF is that??

Everytime I see those two pics of George and John, side by side, I think about how the difference is body language is just fascinating!

Struck me as well

John annoyed, probably with a short fuse. Trying to relax, in an open but standoffish pose. Probably ready to sarcastically bite anyones head off who approaches him.

George is clutching himself, almost trying to shrink down and dissapear. To vanish from this Beatles world and into the comforts of home and anonymity

They both want out of this touring hell

“The rest of the night passes in a fever dream, restless, agitated, stalked by visions of sharp objects and chaos, swarming roaches of energy skittering under my skin and into my skull.”

I’m curious Faith, did this experience happen after the school shooting in Texas? I’m just wondering if that was the impetus.

The picture here of Paul aiming a gun at the camera takes on a sinister tone to me now.

Tell me about it! I shuddered seeing that photo, and that was my first thought (bad timing!) I dislike pictures of Paul with guns, like the one from the RAM sessions. Ugh! Because he and John were fighting at the time, and John ended up getting killed by a gunman. I don’t know; I just don’t like it. Have the others been pictured with guns? Ringo during Help! (I think). Maybe George on the back cover of Rubber Soul? I don’t remember seeing John with a gun. Oh wait, but that was Gripweed in a silly movie (though he looked great).

About the article, I like it for its creative writing style.

I agree Michelle, Beatles and guns don’t mix. Guns go against everything the Beatles stood for. Plus a gun took John from the world.

I also agree about the creative writing style. I do like Faiths writing.

I agree, John did look especially great in How I Won the War. Healthy, young and strong!

It didn’t. This was several months back. I don’t follow the news anymore. After 2016-2020 and esp 1/6, I needed an extended news fast for my mental health, maybe for the rest of my life…

As far as I know, the effect was entirely about the music. There was no obvious external factor that I’m aware of, though of course, there are lots of theories about Rite of Spring, etc. about how historical events can trigger reactions to ahead-of-its-time art.

Thank you for reading!

I should follow your example and quit the news too!

Maybe I was projecting my feelings about the school shooting onto you.

I do really enjoy your writing.

I quit the news around 2016 and it’s been the best thing for my mental health. I realised that the responsibility I had felt towards keeping up with the news was an illusion, and that trying to meet it was doing me harm. Lukewarm takes are much better than hot takes anyway, in more ways than one.

I haven’t watched the news since Trump was elected. I used to be a news/political junkie. If I see a headline and want more details, I’ll search for it. But I don’t sit down and watch the news anymore.

Michelle & meaigs,

Thanks for your replies!

I’ve been a political junkie since 2016. I’m in this weird place where I think if I don’t keep up on what’s happening, I’m not being a responsible citizen. Kind of what you said meaigs. It’s an illusion to think I have control over things by reading everything.

I’m working on balance!

Okay. I read your article. Prepare for THOUGHTS. Because I have them.

1) I would watch a movie about that article.

2) You mention them wanting to tear off their perfectly tailored straitjackets and I’m once again brought to mind of Eminem with his anger at being typecast, and of Kurt Cobain and his disillusionment with fame. I think there’s a lot more that needs to be said about that.

3) It sounds like you had a hell of a night. I’ve had a few musical experiences like that, somewhat. Remind me to tell you about Greta Van Fleet.

…

After I read the article, I got out my phone and transferred Revolver to it. Picked up my headphones. Started listening. Um… what kind of music is this? I feel sub-surface rage. I feel lost. Revulsion. And then I feel lost, again. What is going on? I keep getting startled. I screamed once. I feel like I don’t know what music is. What the bloody hell are they channeling? It’s very liminal. They’re at a crossroads, perhaps?

Every time a new song comes on, I’m surprised. Because whatever is behind the songs, whatever is driving it, feels like it should be some dark, symphonic death metal. And when it doesn’t sound that way I get shocked. The dissonance. By the gods… It’s making me very uncomfortable. I can see how this album sent you to madness. It might have been easier on me if I’d not used my (amazing! new!) headphones.

All this to say I loved your article. I can’t wait for the next part. I don’t know that I can keep listening to this album. It’s too much for me. Overwhelming, really. I’m going back to emo and metal and Rachmaninov.

Thank you, Kira! Your comment is a writer’s dream — to inspire someone to listen to Revolver in a new way is hard, given how familiar we all are with it. <3

If I was “high on some particularly potent weed” and suffering from insomnia. I’m pretty sure anything would seem claustrophobic. Maybe even Good Day Sunshine and Got To Get You Into My Life, the two least claustrophobic songs ever written.

Interesting. I find anyone singing about having to be with someone everywhere all the time inherently confining. (same category as Sting’s Every Breath You Take and Blondie’s One Way or Another). I think our culture’s fetishizing of all consuming romantic love (aka obsession/stalking) as a good thing often gets in the way of seeing how truly dysfunctional it is to want to be that close to someone all the time, to make them everything in one’s life.

BTW, I love both songs. None of this is a criticism.

Thank you for reading and commenting!

Finally, a Revolver piece that fully gets to grips with the eerie, alien darkness I sense at the core of the album. Thanks for sharing Mike.

.

Superb writing, and a perfect evocation of the essential coldness of Revolver’s heart, less the off-putting featurelessness of an office block and more the awe-inspiring self-sufficiency of outer space. That same coldness you get on Bowie’s Low, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, the VU’s self-titled, Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” and Kate Bush’s The Dreaming, that urban-paranoia vibe that’s inseparable from late capitalism and relates its subjects’ nameless suffering back to them.

.

I’m in a poetic mood tonight. Must be because it’s my Name Day. Peace all.

So glad you liked it, @Justin, and great to see you again. Part II’s coming soon.

“Finally, a Revolver piece that fully gets to grips with the eerie, alien darkness I sense at the core of the album” — yes yes yes and yes. A kindred spirit, you are…

Revolver has a cold, cold heart — what an exquisite way to say it and so true — and that’s it’s power. (And btw, great observation re: I Feel Love and the other examples. I’m also thinking of Bowie’s Heroes.) I’ll be really interested to hear what you think of part 2 re: Pepper.

Thank you for reading and for your lovely words about my writing! I feel like I’ve found a home for my Beatles thoughts here, thanks to Michael’s willingness to create a safe haven for Beatles iconoclasts.

Well this brings back memories. There was a time in my life when I didn’t really consider an album “heard” until I’d experienced it high on cannabis and with headphones.

I was the one in high school in the ’70s with a good connection. And then later in life, I was the one with two good connections, so if one guy couldn’t come through I could call the other guy. This was important.

Every new album, the first few times I’d play it through regular speakers, just to get a sense of the songs and melodies. And then finally when the time was right and the moon was up, the album cover became a surface for scraping buds with the rolling paper’s cardboard. Twist up a fatty and get the record on the turntable.

Hearing Beatle albums high, I’d appreciate the stereo separation (despite Lennon’s “Back To Mono” advocacy) because my awareness could float between the various instruments. I could admire Paul’s bass while hearing John’s rhythm and the intricacy of George’s various guitars… all the while feeling like I was sitting in front of Ringo’s drum kit.

I remember once obtaining some Thai sticks that were so potent you’d take one hit and then forget you were holding the cigarette in your hand. I heard Abbey Road under that particular influence. Astonishing melody on top of melody on top of melody.

I remember once around 1985 or so listening to Sgt. Pepper’s high and with headphones a few days after I’d seen Citizen Kane and I could perceive concretely both works of art being simultaneously old and new. The 1940s Orson Welles camera work had looked like the 1960s to me, and the 1960s George Martin production sounded to me like the 1980s. Both works of art being of their time while simultaneously pointing to a future time.

By the time “Free As A Bird” came out I’d gotten seriously into edibles. John sounded like he was in one tiny room (almost coffin-sized) while the Threetles sounded like they were accompanying him in a concert hall millions of miles away.

It still bugs me there’ll be no more new Beatles albums to enjoy.

Anyway, where was I?

Okay, clearly a piece explaining why mono is the ONLY way to listen to pre-Abbey Road Beatles is required… I can’t even fathom listening to Revolver or Pepper in particular in anything but mono — there’s too much missing in the stereo mixes and mono gives it an even more claustrophobic quality. I actually spent the $300 for the complete mono set because it’s not on Spotify and it was driving me nuts (though not in a Revolver trip kind of way…) But that is entirely subjective, of course.

Did I just accidentally start a sub-thread about mono vs stereo — oops…

Anyway, thank you for the comment. And yeah, there is something about that combination of factors that really creates a space to experience the music in a way that doesn’t seem quite possible any other way.

BTW, it’s tragic, of course, that was the reality, but I will always smile when I read or hear “Threetles.” To me, it shows their bond so beautifully, as well as their ever-present sense of whimsy, irreverence and wordplay.

And now I think I’m off to munch on an edible and listen to Abbey Road — that one I haven’t done yet, perhaps it will inspire another post… since it’s my favorite Beatles album (closely tied with Everyday Chemistry and Revolver).

I agree completely. I think John was right about the stereo mixes robbing the Beatles of some of their power. Especially the early stuff. The mono mixes have much more punch.

I guess I’ve always associated headphones with the appreciation of stereo. Whenever I had a mono record I’d simply listen to it through my speakers. I think I’d feel excessively claustrophobic if I listened to any monaural record through headphones. It would be too much. I would feel uneasy. I mean, mono doesn’t exist in nature. If we were physically present at a Beatles performance we’d hear stereo.

I know the extreme stereo of some of the Capitol releases is wrong, the mixes with Paul’s voice in the left channel and Ringo’s drums in the right channel etc., and I understand why John hated it. But in my altered state with headphones, it made it easier for me to float around the recording studio like a flying worm, in and out of the drums and guitars and voices and orchestration. The experience was like deconstructing their music and really hearing each part.

Just seen that Faith is a regular commenter here, so my thanks should go to them directly – great article Faith!

Thank you!!!! I’m looking forward to hearing what you think of part 2.

[…] Previous […]