- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

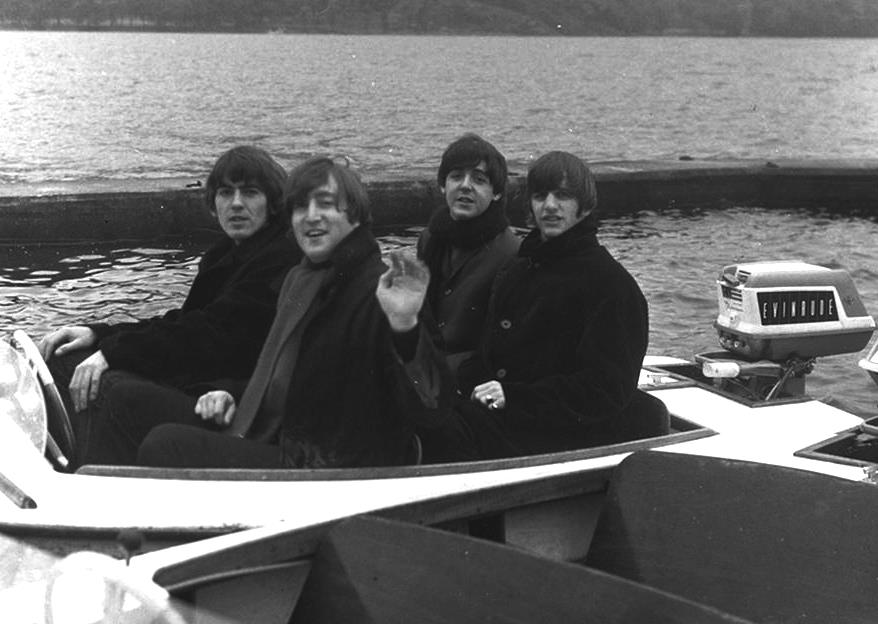

Getting ready to perform, during the suit-and-tie era.

Ron Howard’s Eight Days A Week documentary of the Beatles’ touring years is excellent. Not perfect, not a definitive look at the totality of the Beatles’ career, but very good at doing what it sets out to do. Howard does shy away from the unseemly elements of the Beatles’ life on the road, most obviously the rampant sex.

And he doesn’t delve into the disenchantment that Lennon and Harrison later expressed about the experience of being Beatles. But Howard is aiming to show us what being on public display felt like for the band, and how that affected the Beatles and their audience. Eight Days A Week moves at a clip reminiscent of A Hard Day’s Night, making it all the more amazing to realize just how fast things were changing. Here’s my list of five reasons to watch the film, currently available on Hulu.

5. Press conferences. The film includes enough of these to build a reasonably complete picture of the way the Beatles interacted with journalists. Of course there are zingers, as when John responds to a reporter’s asking how the band keeps zest in its performances with “we do the zest we can.” One of the more unexpected moments comes when a reporter asks why the Beatles give such “horrible snobby answers.” Paul pushes back, saying that they aren’t snobs and that the band can’t give nice answers to questions that aren’t nice. The Beatles look very young to be facing this sort of concentrated press attention, but also very united. (See #2.)

Paul and George share a microphone.

4. Social context. Howard highlights key issues in the 1960s without getting bogged down. The best example is his handling of the Beatles’ 1965 performance at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida. Rather than give us an historian talking about racial tensions at the time, Howard shows us the Beatles at a press conference saying that segregated audiences make no sense to them. We learn that when the band added language to their contract stating that they couldn’t be required to play before a segregated audience, it led to the integration of stadiums across the south. And we get an interview with an African-American woman who was at the show and remembers it as her first experience of being in an audience with white people. Foregrounding personal experience in this way is much more powerful than than the learned talking heads that populate some documentaries.

3. Mania. The sheer immensity of Beatlemania is astonishing to watch. To see the footage Howard assembles here is to realize that, if anything, A Hard Days Night underplayed the hysterical crowds in the streets and at the shows. And by showing us what the crowds looked like from the band’s perspective, we see the terrifying underside of that enthusiasm. Because their audience was so huge, the Beatles were constantly breaking new ground in performance. Bands hadn’t played stadiums before, so no one knew how to handle the sound or the logistics. The Beatles end up playing stadiums with 100-watt amps and getting hauled off in a metal van with no seats. Every other large-scale tour and high-profile band learned from their experiences.

Ron Howard, Ringo, and Paul talk about the film.

2. Camaraderie. The Beatles survived as long as they did because they were adept at playing off each other. In one interview scene, George repeatedly taps the ash from his cigarette onto John’s head, while egged on by Paul. It’s partly a performance for the press, but it’s mostly a snapshot of the kind of clowning they used to take the edge off. Whether they’re at a press conference, in a car, or performing, they read each other’s moods and sometimes complete each other’s sentences.At the press conference where John apologizes for his “more popular than Jesus” comment, the discomfort he feels is mirrored by the other three. While this all for one, one for all quality would evaporate in the Beatles’ later years, they retained their ability to read and respond to each other to the end (see #1).

1. Music. Howard wisely includes plenty of footage of the Beatles performing. (Those of us lucky enough to see the film in a theater also got to see a 30-minute cut of the band playing Shea Stadium in 1965). It’s a tonic to see a film about the Beatles that doesn’t go the biopic route, but focuses squarely on what made the band matter then, and continues to make them matter today. The few studio scenes are well-chosen to show the process of building a song, and nothing illustrates the band’s interconnectedness as clearly as the performance scenes. Even on the rooftop, they are trading looks and lines, moving in coordination just as they did on the Ed Sullivan Show. The tightness of that final performance is both a triumph and a deeply sad coda.

Great review, Nancy — I’ve been swamped with Bystander stuff so I haven’t gotten to see it, but I hope to this week. It’s right down the street here.

One thing, though, that gives me pause: how on earth could anybody claim to address the Beatles’ touring years — especially focusing on their experience of it — and not deep-dive into the sex and drugs aspect? They fly into a town and play the same set as yesterday for a half-hour; then spend the next 18 hours shut up in a hotel room in, say, Milwaukee. It’s not too much to say that taking drugs and having sex must have been their main occupations, or pre-occupations, from 1962-66 — what else could they do?

I still remember that bit in Albert Goldman were we learn about a woman who slept with John Lennon in 1966, when they played Hong Kong; it was the first time he’d ever seen contact lenses. “Great night! Great night!” What do you think John remembered more, the gig or the lady?

I don’t usually say this, but here’s where we really miss John Lennon. If he were alive he would’ve insisted on a 360-degree view of the experience, not one sanitized for mass consumption, marketing purposes, or both. Sex and drugs are what made the touring possible for them; and for sure it kept them interested years longer than they would’ve if it had just been about the money.

This isn’t just prurient interest, either — the Beatles’ Satyricon reflected changes at the heart of Western society at that time, and in this aspect, like so many others, they paved the way for all who came after. I am always troubled by the marketing of The Beatles as family-friendly, for two reasons: one, it’s a distortion that feeds into sex-negativity and shame; and two, it’s an example of commercial concerns shading an artistic legacy.

OK, it’s a little prurient interest

It’s certainly fair to say that without the sex (drugs do get mentioned, particularly with “Help!”), the story of the touring years is incomplete. But I can also see why Howard didn’t try to deal with it in this particular documentary. It would have to be covered by talking heads (unless someone’s out there hiding valuable footage!), and two of the people whose actions would be discussed are dead. I can imagine it could also be tough to find fans who would come forward and talk about the sex.

The film is certainly intended for mass consumption, but I think what it does show is valuable.

Oh, for sure. I’m glad it exists. It’s just… you get what I’m saying, don’t you? It’s like a biography of Mao Zedong that doesn’t mention the Cultural Revolution — you can understand why they elided it, but that decorousness makes it impossible to get a clear read on the topic in question.

I can imagine it could also be tough to find fans who would come forward and talk about the sex.

Oh, I am SURE there are fans who would tell their stories, and on camera, too. But I’m also sure that neither Paul nor Ringo would’ve OK’d that. The moment you talk about sex on tour, you get into the rumors of paternity, etc. And you can understand why Paul nor Ringo would want to open that up. Who does it benefit? Only historical accuracy, and historical accuracy doesn’t get a vote.

But here’s why it matters: tonight supposedly Gennifer Flowers is showing up at the Presidential debate. This is appalling, and it’s happening because Americans cling to a fundamentally squeamish and childish view of adult sexuality. Dealing truthfully with the sexual behavior of and around the Beatles is a way to grow everyone up a little bit, in a way that harms no one.

I do see what you’re saying, and agree with you about puritanical attitudes toward sex.

On the practical level, I think trying to vet stories of fans who’d had sex with a Beatle would be a nightmare. “Did YOU have sex with John, Paul, or Ringo? Call this number . . .” So I revise what I said earlier: it might be easy to find claimants, but hard to tell who was being truthful.

Howard could have acknowledged the sexual behavior of the Beatles on tour without getting graphic about it, and I think the film would be stronger if he’d done that.

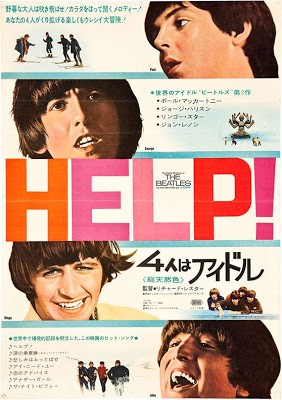

I snuck out for a noonday matinee showing of Eight Days A Week and I enjoyed the experience. I literally have not seen the Beatles on a big screen in a movie theater in 51 years (I saw Help! in 1965 at our local cinema at the age of seven) and loved the big, cleaned-up sound and restored footage.

.

Usually I’m annoyed by contemporary talking heads, but everyone interviewed (Whoopi Goldberg, Eddie Izzard, Elvis Costello, Mr. Kane) had valuable things to say. While watching the footage I sort of felt myself reaching back into time to shake hands with my childhood self: “It’s the future! 2016! And I’m seeing this great Beatles movie. Trust me! You’ll love it!”

.

Because it was a weekday matinee, the only other people in the audience were three ladies who appeared to be in their late ’60s/early ’70s. They talked excitedly through the whole thing, but I enjoyed their comments. They chuckled at John’s wit, giggled whenever Paul spoke. The soundtrack volume was loud enough so that they were simply quiet murmurings. When the documentary ended, they all got up to leave. I turned around and told them “The Shea Stadium concert is coming up next” which surprised them. They sat back down and sang along with all the songs. At the end of the film, the leader of the group (the granny equivalent of John) thanked me for letting them know about the bonus footage.

.

I confess I felt myself choking up a few times during the movie, and actually had a tear in my eye more than once. But then again, I’m sentimental that way.

.

I like how it ended with the beautiful rooftop footage, I simply enjoyed the whole thing. The Shea Stadium concert was fun to watch, especially John’s keyboard work on “I’m Down” and the views of the crowd. A scrapbook of madness, to be sure.

.

If any of you have the opportunity to see it in a theater (rather than Hulu or a laptop or whatever) I recommend it.

I’d also like to say how good it was seeing Howard Lindsay Goodall CBE in the documentary. He gave a valuable explanation of their songwriting talents, comparing their achievement to the classical boys like Mozart.

And when I thought I couldn’t love the Beatles any more Dr. Kitty Oliver shared her memories:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mAR5jAHtmSo

Ping! Spam advertising in the first paragraph

Fixed! Thank you kindly