- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

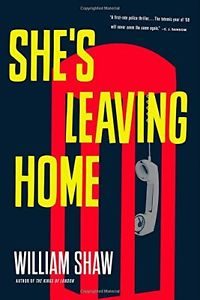

William Shaw’s She’s Leaving Home is a Beatles-linked police procedural mystery. It’s also a deep dive into the turmoil of late-60’s London. And an examination of two detectives struggling with their identities and social roles. If that makes the book sound overstuffed, it’s because it is. But overall it’s an enjoyable read for Beatles or mystery fans who are prepared to skim a bit.

William Shaw’s She’s Leaving Home is a Beatles-linked police procedural mystery. It’s also a deep dive into the turmoil of late-60’s London. And an examination of two detectives struggling with their identities and social roles. If that makes the book sound overstuffed, it’s because it is. But overall it’s an enjoyable read for Beatles or mystery fans who are prepared to skim a bit.

Beatles novels are as various as the songs on the White Album, ranging from the simply parodic (Alan Goldsher’s Paul is Undead) to the thriller (Phil Rickman’s December) to the realistic slice-of-life (Philip Gillam’s Here Comes the Sun). But alternative history leads the field, with varying degrees of comedy and literary weight (Mark Shipper’s Paperback Writer, Larry Kirwan’s Liverpool Fantasy, our own Michael Gerber’s Life After Death for Beginners, Kevin Barry’s Beatlebone).

In Shaw’s novel fictional members of the Apple Scruffs are major players in the plot, but the Beatles are mostly an offstage force. The young murder victim is killed and dumped near the EMI studios, and determining her identity involves a searching look at the Beatles Fan Club and its files. The unspooling investigation, led by Detective Sergeant Cathal Green and Constable Helen Tozer, highlights a changing England in which the sexual revolution is taking hold, immigration is a controversial issue, and formality is loosening in favor of youthful energy.

Shaw’s at his best when describing the look and feel of London at the time. Here, for example, is Breen’s perspective as he walks to a bus stop:

“West London was full of color. Each year the colors got louder. Girls in green leather miniskirts, boys in paisley shirts and white loafers. New boutiques selling orange plastic chairs from Denmark. Brash billboards with sexy girls in blue bikinis fighting the inch war. A glimpse of a front room in a Georgian house where patterned wallpaper had been overpainted in yellow and a huge red paper lampshade hung from the ceiling. Pale blue Triumphs and bright red minis parked in the streets.” (34)

Interesting as many of Breen’s musings are, his complicated backstory takes up far more space than it warrants. Whenever the book turns to Breen’s efforts to overcome a fall in status among his fellow officers or deal with his father’s recent death, it drags. But Shaw writes convincing dialogue that gives the characters depth and brings the time period to life. When Breen asks an EMI caretaker what the crowd of girls standing outside the studio want, the caretaker responds “They just want to be close to them . . . . It’s like they think if they can only get to them, everything will make sense. People think they must have the answer to everything. It would drive me mad. Wouldn’t it you?” (52)

When the investigation leads to the Beatles Fan Club, Tozer’s long-standing membership in it helps her get information from the club’s fictional leader, Miss Pattison. The Scruffs question Tozer extensively to determine whether she’s actually the fan she claims to be (she emerges triumphant, a true George lover). Tozer’s efforts to educate the older Breen about the way Beatles fandom works take a predictable tack:

Apple Scruffs

“I bet you don’t even have a favorite Beatle, do you, sir?”

Breen shook his head. “I missed all that,” he said. “Too old.”

“I never met anyone who didn’t have a favorite Beatle. Even my gran has her favorite.”

“Who’s that?”

“Paul McCartney, of course.” (91-92)

Such conversations, along with the descriptions of London and the practicalities of the investigation, are the strongest parts of She’s Leaving Home. It sometimes feels as if Shaw had enough ideas for at least two novels, and couldn’t bear to cut anything. Thus we get a group of suspects protesting the British colonization of Africa, an abusive father, a secret lesbian relationship, and multiple scenes illustrating the prejudice Tozer faces as a female police officer. When things finally get explained, it’s a relief to be done with the overly complex plot. More focus on Breen and Tozer’s working process, and less on Breen’s backstory or Tozer’s struggles with chauvinistic fellow officers, would allow Shaw’s strengths as a social observer to shine. Here, for example, Breen notices two hippies outside a record store as he and Tozer walk past:

“These people were only a few years younger than Breen, but they lived in a different world. Men of Breen’s generation had grown up wanting to wear better suits than their fathers. This lot didn’t want suits. They weren’t looking for careers, weren’t waiting to enter the world of middle age. Gazing at Breen they seemed to say, ‘Everything you stand for is ridiculous.’

The shop’s glass was covered in gaudy posters for groups with names like the Pink Floyd, the Nice and the Pretty Things, hiding whatever lay behind. The two hippies didn’t take their eyes off Breen and Tozer as they walked past. Peace and love be fucked.

England dividing itself on new lines.” (93)

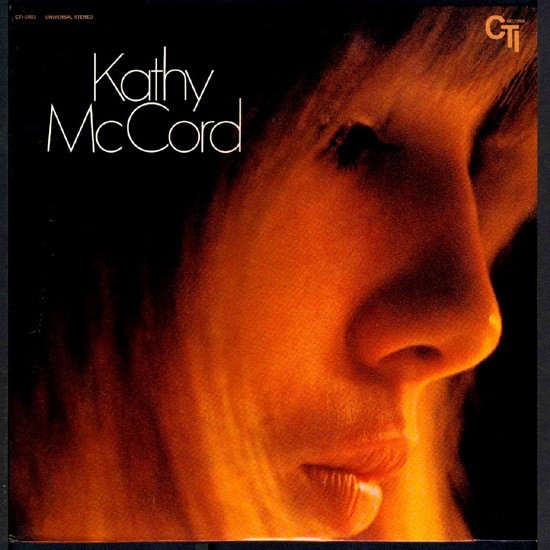

Beatles references figure throughout the book, as when Fan Club members mark time by events in the Fab Four’s lives (Paul’s breakup with Jane Asher, the release of “Hello, Goodbye,” etc.). The only time one of the Beatles appears is when Breen and Tozer witness the mob scene that follows the emergence of John Lennon and Yoko Ono from court after being charged with drug possession,:

John Lenno and Yoko Ono in 1968, after being charged with drug possession

“A ring of police helmets showed above the rest of the crowd. Somewhere in the middle was the pop star, making his way slowly to the waiting vehicle, a tiny dark-haired woman in a fur coat that made her look even smaller clinging to him.

‘Do you feel you’ve let your fans down, John?’

‘Were you set up?’

‘His girlfriend had a miscarriage on account of all of this,’ said Tozer.

‘What’s that?’ said Breen.

‘They said it in court. That Japanese girl Lennon is going out with. She had a miscarriage because she was so upset by it all.’

‘Her fault for hanging around with a druggie, then,’ said Carmichael.

‘He looks smaller in real life, doesn’t he?’ someone said.

‘He looks scared silly.'” (261-62)

Fittingly, the novel ends with the two detectives listening to the White Album. Breen is surprised by how much he likes it, while Tozer’s verdict reflects her longstanding attachment to the band: “I mean, there’s good stuff on it, but it doesn’t really sound like the Beatles. Most of the time it sounds like four blokes doing weird stuff. It’s not really the Beatles anymore . . . . It makes me feel sad. It sounds like they’re falling apart.” (413)

The Swinging London backdrop and Fab Four references make She’s Leaving Home worth reading for Beatles fanciers. However, I’m not convinced that Breen and Tozer, minus the Beatles link, are going to join the likes of Morse and Lewis or Lynley and Havers. For those interested, Shaw has followed up She’s Leaving Home with another Breen and Tozer mystery, The Kings of London, which apparently features Beatles-linked art dealer Robert Fraser as a character.

Thanks for that review. “She’s Leaving Home” would make a fine movie (with the right director and screenplay and a Beatles soundtrack).