- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

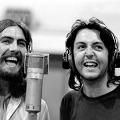

Whenever our commenters start griping about the perception of John Lennon as the leader of the Beatles, I always think of this poem, written by Allen Ginsberg in 1965. It’s a good poem…and it also speaks to how people perceived the group in 1965. Reversed to give emphasis, Ginsberg’s perception of the members’ relative power was just as they were endlessly advertised: John, Paul, George and Ringo.

“”Portland Coliseum”

by Allen Ginsberg

A brown piano in diamond

white spotlight

Leviathan auditorium

iron run wired

hanging organs, vox

black battery

A single whistling sound of ten thousand children’s

larynxes asinging

pierce the ears

and following up the belly

bliss the moment arrived

Apparition, four brown English

jacket christhair boys

Goofed Ringo battling bright

white drums

Silent George hair patient

Soul horse

Short black-skulled Paul

with the guitar

Lennon the Captain, his mouth

a triangular smile,

all jump together to End

some tearful memory song

ancient-two years,

The million children

the thousand words

bounce in their seats, bash

each other’s sides, press

legs together nervous

Scream again & claphand

become one Animal

in the New World Auditorium

—hands waving myriad

snakes of thought

screetch beyond hearing

while a line of police with

folded arms stands

Sentry to contain the red

sweatered ecstasy

that rises upward to the

wired roof.”

Why is it important to acknowledge the perception of John as “The Captain” (echoes of Whitman)? Why is this paradigm useful to us, even today? There are several reasons:

1) It gives the original history, and original perceptions, pride of place. The Beatles story isn’t a mass of facts to be arranged however an individual fan likes best; it is a clearly defined and bounded historical object which acted on its time and was acted upon by it in perceptible ways. It’s not a limited TV series based on true events, or the BCU, or fanfic. Within this defined and bounded historical context, things like name order don’t matter—except when they clearly DO. That’s the way the group members are listed in the vast majority of instances. Whether “J/P/G/R” happened simply for PR reasons (“Brian says”), or whether it reflected the internal politics of the band (“John wants to be first”), that’s how the group was put forward in the 1960s, and today as well. It’s not random; have you ever heard The Beatles referred to as “George, Paul, Ringo, and John”? Why not?

2) Lennon-as-leader, then abdicator or deposed, explains the trajectory of the group. Whether Lennon’s story in 1970/71 reflected the whole truth or just a kernel of it, the trajectory of John being the leader in the period from 1962-66, growing confused/bored/disenchanted, and then Paul leading the studio years, fits perfectly with the changes in the Beatles external presentation and musical development. With all due respect to Faith’s recent posts, there are clear and obvious differences, sonically, tonally and in presentation between Revolver (John-led; Paul even stormed out of the sessions, the first Beatle blowup) and the Paul-led Pepper. Pepper is the band’s obvious turning-point, their fulcrum. John-as-leader is useful; it isn’t merely a concept to devalue Paul, it actually emphasizes his gifts, explains how the group developed, and why. To some degree, it explains why John acted the way he did after India—he was angry at his loss of leadership. And it explains Paul’s behavior too: his mollifying, his putting up with John’s appalling behavior as a marker of respect for the ex-Chief. It even explains why George and Ringo, no dummies, agreed to have Klein represent them; they were recognizing John’s old leadership, and rejecting Paul’s new reign. Lennon/McCartney as even-steven partners from the beginning doesn’t explain the Revolver/Pepper shift, the tensions in 1968-69, and the breakup. Lennon leading at the beginning and Paul leading at the end does. Plus, that’s what John himself said, and Paul allowed him to say without fierce pushback, between 1970-80. What we prefer simply doesn’t enter into it.

3) A single “Captain” reflects how these kinds of group creative endeavors seem to start—especially back then—and the rise of the talented second banana is commonly the rich second act. In Beyond the Fringe, Peter Cook was first among equals; in Monty Python, John Cleese was first among equals. Both were rageful men, big attractive acid-tongued personalities who burned to become famous, and were recognized immediately as the “leaders” of their extremely talented groups. In BTF, Jonathan Miller was probably #2, with Moore and Bennett as the “economy Fringers.” In Python, the writing team of Terry Jones and Michael Palin were #2, with Chapman, Idle, and Gilliam as the “economy Pythons.” In the Beatles…well, you know. Among the Fringers, Cook flamed out after 1967 or so, when the original “Satire Boom” idea had run its course, with no real idea of what to do next—while his collaborator Moore continued to work in conventional showbiz and garnered worldwide acclaim. In Python, Cleese had actually quit the group for a bit in ’74, wanting to be recognized on his own and working furiously on “Fawlty Towers” (his “Plastic Ono Band”) to make that happen. In the Goons, Milligan—the leader of the gang during the radio show—was eventually vastly outshone by his less quirky, more ambitious, more conventionally appealing #2, Peter Sellers. All these creative groups of men began with a general hierarchy, with one big personality at the top providing a certain kind of drive. Then after that arrangement leads them all to great success, the #2s start to stretch out, and make their mark, and the period where the group is led by the #2 creates a same-but-different all-important second act. The Python TV show (Cleese-led) feels very different than Life of Brian (directed by Terry Jones); “Flying Circus” is wonderful but dated, just like “A Hard Day’s Night.” The test of one of these groups is whether the original leader, and original pecking order, can be changed without the group imploding. With Beyond the Fringe or The Goon Show, it was impossible, and that makes them lesser when compared to the Pythons and the Beatles, groups who were able to shift, and add to their legacy. And really valuable parts to their legacy, too—just as The Beatles would be strictly an oldies act if they’d stopped recording in 1966, The Pythons would be fundamentally less influential and beloved and long-lasting if they’d broken up after the show’s fifth season, when Cleese decided he’d had enough. Just as the Paul-led Beatles still contained John, and produced a second act which is richer and more widely consumed today (Pepper/MMT/White/Abbey Road), the Jones-led Pythons still contained Cleese, and produced Holy Grail, Life of Brian, and Meaning of Life, the richer, deeper, more developed work that most people associate with them today.

Hearing how—and understanding why—Beatles music seems to fall into two distinct periods (1962-66, and 1967-70) is fundamental to understanding The Beatles story, which is not ours to fashion, but to learn. And the John-as-leader followed by Paul-as-leader paradigm explains that story; it maps closely onto not only the music and the presentation, but also the group’s interpersonal journey as it has been related by the members themselves. And it reveals what makes The Beatles so special: their democracy within the hierarchy, and an ability to change, to adapt over time, and have that all-important McCartney-led second act.

I really liked this Michael, and I think you explain clearly the roles of John and Paul in the Beatles.

I liked your examples of other groups with similar dynamics, such as Monty Python. I think it’s spot on.

“All these creative groups of men began with a general hierarchy, with one big personality at the top providing a certain kind of drive. Then after that arrangement leads them all to great success, the #2s start to stretch out, and make their mark, and the period where the group is led by the #2 creates a same-but-different all-important second act.”

As you said, the J/P/G/R order is not random. Here’s an excerpt from “Tune In” that confirms this:

“Neil (Aspinall) would often emphasize (sometimes finger-proddingly) that there was one essential key to understanding the Beatles psychological constitution, as true in 1962 as it would be in the twenty-first century. He called it “the Chain”. John brought in Paul, and Paul brought in George, and George brought in Ringo.

John, Paul, George and Ringo doesn’t just trip nicely off the tongue, it was (is) a natural order, and connections of great intimacy wend within and without its links.”

Great comment, Tasmin, and great post, Michael. Revolver and Sgt Pepper have psychedelics and experimentation in common, but on Revolver, Paul is still working within John’s framework for what a Beatles album is. And on Sgt. Pepper, the reverse is true.

There’s a significant difference between analyzing what contributions Paul made before ’67, or John made after, and arguing that John wasn’t the leader through ’66 or Paul wasn’t after. One of those is an exploration of the group’s creative process. The other is a very Internetty, 2022-style exercise in denying and rewriting facts to satisfy an emotional need.

I was in kindergarten when the Beatles made their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. It was the first time I saw them. I immediately perceived John as the leader because of their positions onstage. John with his own mic, and Paul and George sharing a mic. And John was more prominent in the CBS camera angles.

The next day my father came home with the Vee-Jay album (as requested by my teenaged siblings), so this was the first official portrait I saw of them. And again, John was prominent, seated in the middle and surrounded by the other three.

Years later, after I’d read books and articles about them, I was struck by how vital to the band each member was, despite John being the clear leader. So many other bands were basically a lead singer backed by a group of members that could change from month to month, often picked by management.

Very interesting piece! As always, I really appreciate the focus on the evolution of the group and how that maps onto a wider context (esp. historically). I completely agree with your concluding statement – one of the reasons why the Beatles is one of only two musical acts whose discography I ever listen to from start to finish is precisely due to the range of musical influences and trajectories the Beatles explore over the course of their partnership (especially post-Beatles for Sale – though I have an admittedly enormous soft spot for the early albums). Obviously they are not the only band, act, or artist that have explored various different genres of music over the course of their career and made those transitions effectively, but I don’t think I need to justify a personal preference for the Beatles’ music on here 🙂

I am intrigued by the interplay, both thematic and chronological/historical, you and Faith have brought up between Revolver and Pepper if we think of Revolver as Lennon’s final charge at the helm and Pepper as McCartney’s first – even just comparing covers, the pencil caricatures and Cubist-like collage of images on Revolver could be seen as representing a dehumanisation that echoes across many of Lennon’s lyrics, where Sgt. Pepper’s is the commodification of that dehumanisation into an art pop, conceptual plane of rainbow displacement (“we hope you will enjoy the show”). Pepper sees The Beatles as other than themselves – it is a deliberately constructed world not out of the black-and-white collage of Revolver’s “reality” (if either can be called that), but a fantasy in full-blast Technicolor. Where Lennon leans more towards a drive to express “authenticity”, McCartney revels in the spectacle. However, as has been previously said on this site, only dichotomising Lennon-McCartney misses their fundamental symbiotic process. One can argue that Revolver is as much of a constructed experience as Pepper, in the same way that “authenticity” can be revealed in Pepper by considering how and why the spectacle has been crafted.

How Lennon and McCartney fared in the “turn” in leadership is an excellent analogy; the Revolver-Pepper “turn” you describe could be read as both a shift as well as a turn to look back, to reflect in both senses of the word, to mirror and refract (with kaleidoscope eyes, perhaps?) what has come before and what their musical partnership presents before them.

Nothing that many others haven’t already said before (I don’t mean to wax poetic, I swear!); I am still waiting to get my hands on a few important Beatle books so I can have a better understanding of the exisiting literature on and analyses of their body of work), and my thoughts are a bit scattered and elegiac, but suffice to say your post provided great food for thought!

@Ava, I’m glad you liked it.

Evidence of the “turn” is simple: just look at Revolver and Pepper. JUST LOOK AT THEM.

Both are photo-collage, but they could not look more different.

Revolver was drawn, in black and white, by someone from The Beatles Hamburg days. It is very “flat.”

Pepper is a color photograph taken by Jann Haworth and Peter Blake. It is art-directed by Robert Fraser. It is very 1967 London. It is very “3-D.”

The Beatles clearly had approval over the packaging of Revolver, but it was also not so dissimilar from Rubber Soul; groovy conceptual cover, with publicity-style photos on the back cover. No gatefold. Plain inner sleeve. Revolver’s packaging is meant to be appealing, but it does not consciously view itself as offering a total experience, a visual equivalent/compliment to the Beatles’ aural offering.

The packaging of Pepper is meant to reinforce the music– and “concept”–in as powerful a way as possible. Pepper is meant to be an experience — that is why there’s a gatefuld, lyrics on the back, sumptuous color throughout, a designed paper sleeve, a set of inserts.

Revolver is a beautiful, well-designed, completely thought-out cover; Pepper is a beautiful, well-designed, completely thought-out PACKAGE, and that makes all the difference. Brian Epstein knew how big a step it was—that’s why he made his “last wish” “brown paper bags for Pepper.” He didn’t get what they were doing with Pepper and why it was important; but Paul did, and it’s because Paul was steeped in the London art scene, and counterculture, in a way that Brian wasn’t.

Revolver is wonderful–I LOVE Voorman’s drawing–but it is not epochal. Pepper’s cover is probably the image people will pick when “psychedelia” is spoken of in 2067.

I respect your opinion, Michael, but you’ve lost me completely. It is not even the point of my argument (or gripe if that’s your drift) and a departure from the original premise: John without Paul and Paul without John. One would have to be an idiot to challenge the John/Paul/George/Ringo lineup. Why? Because it’s never been a problem. If anybody thinks the Beatles had two distinct musical periods, then that’s what *the* books and money grabbing music publishers have told them as far as I’m concerned. For marketing purposes, if a line has to be drawn, then it has to be drawn somewhere, doesn’t it? Sonically and stylistically, there was a good deal of overlap 1965 to 1967, which marked the natural progression and development of John and Paul’s songwriting and sound, jointly or singly, throughout the whole period. Why would either of them be writing the same type of song in 1966 as in 1963? Is there really any point in splitting hairs? But I’d have to say it’s disingenuous to imply Revolver was John led because Paul left the studio angry during the recording of She Said She Said – one song – where the reason is speculative but not known. Yes, Sgt Pepper was Paul’s idea, conceptualized during limbo after the end of touring. The others were involved in other projects without him. Pepper was HIS project. One can intellectualize and overegg the Beatles story ad infinitum (and references to Cook, Clease, Ginsberg, et al, does essentially that). Despite their squabbles, John and Paul worked far more closely and collaboratively than their respective fans care to admit, and John and Paul themselves cared to admit.

I respect your opinion, too, @Lara, so let me see if I can “find” you again. 🙂

I read every comment lobbed into this long-suffering site, and over the past five years or so, many—perhaps the majority—have either been Paul fans trying to defend their guy, or John fans trying to defend THEIR guy. My stance in the midst of this tribalism is to say that the important thing is not John OR Paul, but John AND Paul.

But that is not the only valid paradigm. These were two distinct talents we are talking about, each with strengths and weaknesses, who developed in a complimentary way due to youth, but are not the same, and seemed to diverge—as one would expect—as they aged and their talents matured. So considering John without Paul or Paul without John is not only appropriate but necessary.

Because Paul is perceived to suffer unduly in what they call “the Standard Narrative,” Paul fans increasingly deny the presence of ANY hierarchy within The Beatles, and this site has hosted long threads about this. But I believe, not just from the historical record, but also the music, and also my decades of working with creative teams, that there was a discernible and important hierarchy within The Beatles—the J/P/G/R pecking order. And furthermore that it changed immediately after touring, when what it meant to be a Beatle changed from something which John felt in his marrow to something new, a studio-only band which made Paul’s up-until-then secondary role as leader-when-we’re-in-the-studio leader unquestionably primary.

For me, this bifurcation—which is at the heart of “the Standard Narrative”—is actually a sound and useful way of looking at the group and its music, and can be applied to other successful creative endeavors of that time. I’m not “splitting hairs”—I’m attempting to refine the historical record (“this happened, and this is WHY; then that happened and that is WHY”) in a way that comports with the majority of what we know, in an age where a surfeit of data is increasingly used by people to create the past that they prefer. That is the opposite of overintellectualizing the Beatles story; it is an attempt to clarify and simplify it.

“If anybody thinks the Beatles had two distinct musical periods, then that’s what *the* books and money grabbing music publishers have told them as far as I’m concerned.”

This is an example of what I’m talking about. There is no vast external conspiracy to force a two-period outlook onto a passive fanbase; it just logically fits. If you, personally, see the music and lives of The Beatles as one seamless unbreakable evolution from 1962-70, that’s an interesting viewpoint on it, but it’s not really workable as an historical text—there’s too much, and too much change.

The historian’s job is basically this: Start anywhere you like and ask, “What was?” Then, “When did things change? How did they change? Why did they change? What did it mean?”

You can ask these questions about anything. The change between the LPs “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Beatles for Sale,” or you can ask it about Beatle music as it sounded in 1962 and 1964, or John and Paul’s working method in ’57 as opposed to ’64 as opposed to ’70. This isn’t damaging the work; it’s attempting to learn more about it. Perceiving it as a seamless whole is a valid POV, but it’s not the only one, and it’s IMHO not very useful. It’s a bit like saying, “Stop thinking and enjoy the music!” Well, yes, I do that and have done that. And now I think about why “In My Life” sounds so different from “Glass Onion.”

For me, personally, I find the division into two periods, 1962-66 and 1967-70, not only commonsensical but also illustrative. You may not. But I’m not doing it because “they”–the Beatles Industrial Complex–is telling me to. I’m doing it because Sgt. Pepper sounds and looks and feels very different to me than Revolver does, or even Rubber Soul, much less A Hard Day’s Night only three years before; and the work from Pepper on seems to be created in a different way for different reasons with different goals, than the music before it. The fact—that thing I hear with my ears, the difference between “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” and “Day in the Life”–begs for some explanation, and exploration. Far from distorting the music or story, the two-period schema clarifies it for me. Just as considering Paul without John and John without Paul is a useful exercise which doesn’t, and shouldn’t, gainsay their collaboration. Your mileage, as they say, may vary.

A vaguely related thought: regardless of its immediate artistic payoff for the group (1967), was quitting touring the wrong decision for John Lennon personally? If the Beatles had slowed the touring pace, but stayed on the road in some degree, would John have been forced to not get completely immersed in acid and/or have retained that Chief Beatle status, both of which probably underlay the unraveling after India?

There are so many variables that it’s hard to think through this hypo right away. But my first guess is yes.

That’s an interesting question, @Michael. I think John resented–but desperately needed–the rigors of a schedule meted out by an external authority. Paul knew that, too, and tried to supply it, becoming hated by Lennon in the process.

Absent the mania, I think touring could’ve been turned into something artistic–as much an expression as a studio album, although different. I have said before that outfitting Epstein’s Savoy Theater with an endlessly improving sound and light show, with the small, invite-only Beatles concerts being filmed and sent to movie theaters worldwide, could’ve been something that Lennon and the others would’ve loved. It would’ve been easier, more lucrative, and artistically innovative–and could’ve started in November 1966 as the UK’s answer to Warhol’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable.”

Michael, it’s interesting that your description of “the historian’s job” somewhat mirrors the playwright’s. The latter in part is finding the “inciting incident” — or as one of my old teachers used to descibe it, “Why is this night different from all other nights”? (Which, of course, is the Passover seder.)

I heard that dictum in improv class, too, @Marian!

Fawlty Towers (like Plastic Ono Band) was a good outlet for a rageful artist breaking free from the restrictions of a group. I hadn’t thought of that comparison.

I was a diehard Python fan from the first moment I saw them on PBS in the ’70s, but I confess I know absolutely nothing about their internal conflicts. I’ve read nothing about them. Is there a Lewisohn -type book out there about them, or any reliable memoirs?

This reminds me of Brian Jones and the early Stones. Also Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd. I’m certain there are many other examples in music and comedy. Clark and McCullough perhaps. When they started out, McCullough was the dominant one but by the time they reached Hollywood, Clark was the leader and McCullough was reduced to just a few lines of dialogue and cackling at Clark’s jokes.

@Baboomska, I’m glad it pleased. I began writing it unsure whether the pattern would hold, and was surprised at how consistent it was. The other thing about Lennon/Cleese and POB/Fawlty Towers is that after FT, Cleese was considered to be THE genius behind Python, the funniest Briton ever, etc etc…just as John was over-lionized. But then things adjusted.

Kim “Howard” Johnson has written much about the Pythons, so I’d start there. I have a Cleese bio somewhere but haven’t cracked it.

Michael,

While perhaps not directly using the term “Leadership/Followership,” you have touched on this in many of your posts and I find it to be one of the fascinating dynamics behind not only the Beatles, but any successful team effort–whether it be in a creative or technical endeavor.

This goes deeper than just the leader taking input from subordinates. It is that flux and fluidity in which one can be, within the group dynamic, a leader one moment and a follower the next and sometimes both simultaneously. I view it as the “what is right and not who is right” concept in which there is a constant and underlying iteration of the main idea to create or bring forth the best solution. We oftencan’t describe it, but we can certainly recognizethe results.

I agree with the view of John being the leader until the transition of Pepper at which time the center of gravity shifted to Paul, but I still wonder about the John years and how those leadership/followership roles were reflected in the transition period of Rubber Soul and Revolver.

I guess what I am saying is that I think Fandom overlooks the sublelty of this constant role switching in successful small group efforts.

I think feelings for and about the Beatles are emotional. They have touched such a deep place in our souls that it’s hard to be logical about them.

I am a Paul girl, and I’ve found myself getting defensive for him when he’s done something that’s criticized. I’ve also gotten upset when I’ve felt his contributions to the Beatles have been diminished.

Michaels post is logical: it makes sense. We have to look logically and maybe suspend our emotions about the Beatles story. Its not easy.

FWIW (data point of one and all that), I was speaking to a 66-year-old friend of my parents who was a first generation Beatles fan and liked George the best, and she said that she and her friends *always* perceived John as the leader. “He seemed the most confident and powerful.”

There”s a lyric in the Sa-Roc song “Dusty Roads” that reminds me of Lennon:

Wow, that’s a great poem. Reminds me once again why I like Allen Ginsberg so much. Imagine being the coolest creative on Earth for a few years and then so openheartedly ceding the turf to the new kids on the block. The same openmindedness that carried him through the psychedelic and postpsychedelic years with such commitment and grace.

.

I’ve often thought about how the Lennon/McCartney pairing compares to other creative pairings – particularly British comedy partnerships – but never hit upon this first act/second act model before. Really sheds light on the subject.

.

I’ve always seen Cook and Moore as an especially good analogue for John and Paul. Pete/John: wealthier background, idler, more addictive, angrier, wilder, more countercultural, more androgynous, less at home in the world, spoke more forcefully to the era in which they hit their peak, forever the “cool one” to the fans. Dud/Paul: in the shadows at first, more stable, more “old showbiz”/eager to please, harder-working, multitalented/able to turn their hands to anything, longer lives, more successful careers, better able to speak to successive eras, and fiercely resented by their counterparts, who ended up turning on them and being nasty to them in public. In both cases there’s a deep love between the men but a deep competition too; in both cases the “big brother” fails to realise that the “little brother” doesn’t mind being the little brother, looks up to them, isn’t setting out to dethrone them, just has a restless talent and drive that can’t be contained.

.

With Paul there’s been a major effort to redress the balance in recent years, but I haven’t seen the same happening with Dud – partly because he’s much less well-known; partly because Pete is easier to view as an underdog than the iconic Lennon, meaning critics still feel the need to compensate for his lack of career success; and partly because Pete & Dud were always more a British than an American phenomenon, and British critics are far keener on tearing great talents down than their more appreciative cousins in the States. (Plus, in America the work ethic is seen as a virtue, whereas in England it’s a vice. It’s vulgar for entertainment aristocracy, like real aristocracy, to be seen to be working for what they have.) The result being that Dud is talked about as if he were nothing more than a straight man for Pete to bounce his genius off of – whereas when you actually go back and watch the sketches and interviews, he makes the audience laugh at least as much as Cook does, frequently with off-the-cuff one-liners.

.

Notes from an essay I’m currently working on: ‘I’ve noticed that the comedy world is full of successful Lennon-and-McCartney-style pairings, where Guy A is full of strikingly original ideas, but often discouraged and deeply conflicted about their audience, while Guy B is more conventional, but also more productive and eager to please: Peter Cook and Dudley Moore; Graham Chapman and John Cleese; Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld. (Ricky Gervais and Stephen Merchant also fit the model to a point.) The Bs need the As to generate fresh ideas and fight for them, while the As need the Bs to put a shape on those ideas and see them through to the end. Bs often have longer careers and more commercial success, while As enjoy more critical respect and a deeper level of appreciation from the hardcore fans.’

.

Basically, the novelty generator and the skilled editor. Not a perfect model by any means – Cleese is definitely more respected than Chapman – but seems solid enough to work with. Any other suggestions for pairings welcome.

Well thought out post Justin. Lots of good ideas to chew on. One of the reasons I so enjoy this forum.

This is very good, @Justin. Would you write it up as a post for us?

It’s impossible to understate the reverence that Peter Cook was held in, within the Anglo-American comedy business, from 1960-80. I remember reading once that Woody Allen called Cook “the only authentic British comic genius.” I don’t agree with Woody–I think there are many others, even in that generation–but there was something about Cook that absolutely transfixed his colleagues. This is very much like how Lennon seemed to set the tone for an entire generation; it wasn’t just the brilliant work, it was also something unique to him that fit his times perfectly, until it didn’t, and that made him a hero WITHIN his industry.

This past week I was watching “McCartney 3 2 1” with my father; Dad turned to me and said, “He’s really just a down-to-earth guy, isn’t he?” Similarly, an old therapist of mine once worked with Dudley Moore and said, “Dudley was a very, very nice man.” When I look at Cook’s work now, I am put off by the unprocessed rage that oozes out of it, and often have the same reaction to Lennon’s work. As a young man, I didn’t see that, or could look past it; now, as a middle-aged man, both Cook and Lennon strike me as dangerous machines. Necessary, brilliant, but nobody I’d want to be like, or take wisdom from, or have to dinner.

I’d love to @Michael, thanks.

.

I must admit that for all my Dud-boosting, he just doesn’t have that mesmerising quality of Cook’s – you can’t take your eyes off Peter. Partly his height and striking good looks, of course, but there’s an indefinable charisma there as well. I can’t remember who it was that called him a Zen comedian, but it’s a great description – he holds your attention while barely moving. Like Lennon, he screams “leader” at you.

.

But yes, “unprocessed rage” is right. So much so that it often gets in the way of the comedy. He’ll often squash a perfectly good line of improvisation from Dud just for the sake of squashing it, totally killing the “yes and” flow that’s essential to the form and making things instantly uncomfortable (not in a funny “The Office” way, either). Plenty of similar self-sabotage in Lennon’s solo career.

@Justin, I think this is something that isn’t oft-talked about with The Beatles, and it’s Lennon’s weird charisma. Both he and Cook are pretty mesmerizing, and if I could sum it up in a word, I think it’s because they’re…withholding? There’s something fearsomely repressed about both men in performance, and if that’s your cup of meat, you really feel it.

Cook on stage is completely in control, most of all when he’s surrounded by a bunch of major comic talents moving a lot and making a lot of chaos. (Cleese is the same way.) They are a cool, calm, appraising presence at the center of whatever they’re doing. Lennon was similar in The Beatles, and it’s why when he talks to the audience in concert, he seems to be laconic at best, casual, and not really trying to get anything across. McCartney is trying to CONNECT, Lennon is not. It’s about power, and Lennon doesn’t give any to the viewer; nor does Cook or Cleese, whereas people like McCartney, Moore, Palin, etc clearly want you to like them. That’s a completely different transaction. McCartney and Moore are performing; Lennon and Cook are BEING, or seem to be.

The obvious crossover here is “Drimble Wedge and the Vegetation,” where Cook creates a parody of a pop star that would have been massively popular throughout the 70s.

Mike, you’ve just helped explain to me what I like so much about the edgy, damaged icons of that era: their combination of strong emotion and guardedness. Performers who keep things “showbiz”, much as I love some of them, can’t quite reach me on the level Dylan, Lennon, Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, and the Morrison brothers (Jim and Van) can. At the other end of the spectrum, most of today’s white male lost-love ballads not only don’t move me, they actively annoy me. There seems to be some magical combination of cool-guy detachment and buried rage that I find deeply appealing. Not just me, of course: virtually every rock critic of the ’70s too, which is why Lennon fared so much better than McCartney in Rolling Stone for all those years.

.

As you say, McCartney’s mission is to put on a show, and he wants you to enjoy it. The cool guys’ mission is to express themselves, and they don’t (want you to think they) give a damn whether you enjoy it or not. Lennon and Hendrix liked to chew gum on stage, while Dylan has said that he doesn’t feel he needs to interact with his audiences any more than paintings “interact” with you at an exhibition. But all three have these incredibly strong undercurrents that sometimes just BREAK THROUGH without warning, and that can be thrilling. McCartney’s showbiz approach means a more consistent product – I had a great time when I last saw him live – but he’s never going to attempt to “break on through to the other side”.

.

Lou Reed and Bowie are examples of cool dudes who *really* keep a lid on the desperate undercurrents – but oh man, are the undercurrents there. ‘It’s no GAAA-AAA-AAAAMEEEE…’ Meanwhile Jagger, although he seemed like one of the cool dudes back when the Stones seemed edgy, has since revealed himself to be a “showbiz” guy to the core. Hence his rockcrit cred has plummeted over the years.

.

We seem to be dealing with two different kinds of guardedness here: one is basically suppressed rage, making it thrilling to a certain kind of listener, while the other carries on the Tin Pan Alley tradition of regarding songs more as genre exercises than vehicles of self-expression. (‘Today I thought I’d write a song about…’) In the ’60s the first approach was cooler, whereas today the kids prefer the second approach: showbiz’s glossy perfection has made a roaring comeback since the end of the grunge era, while Zoomers view unhinged rage as laughably uncool at best and frightening/abusive at worst. Look at the difference in how people see Kanye today as compared to, say, Cobain in the ’90s. (Interestingly, this trend only seems to apply to *personal* rage. Political and community-based rage have been on the rise for years.)

.

Man, that Drimble Wedge clip is something else – what was IN the drugs in those days? Gotta incorporate that scene into the essay. You’re right, he’s seriously presaging the ’70s here – I had to keep reminding myself I wasn’t watching the Thin White Duke. I have to see Bedazzled now.

Bedazzled is tremendous–the pinnacle of 60’s British comedy, IMHO. It is the blueprint the Pythons perfected.

Speaking for myself, I think Cook and Lennon both have the dark gravitational pull of an addict, and if you grew up around that (as I did), it lends them an attractiveness that is well nigh irresistible. Addicts MUST have this charm, otherwise nobody would put up with their nonsense.

The thing about Drimble Wedge–about all of Cook’s humor–is that I don’t sense any drugs in it at all. Speaking as a comedy guy, it’s a simple reversal from the premise of the sketch (Dud as a conventional romantic pop star; Pete as this icy withholding monster), which is put over by Cook’s good looks and superb chilliness. The alienated, affectless, fundamentally scornful character is a performance that touched something sad, deep and essential in Cook, just as Chauncey Gardiner did for Peter Sellers. So much to say that people like Cook, Moore, Bennett, Miller–the whole Oxbridge crowd–were the last generation of comedy people who DIDN’T seem to be getting high. (Gilliam’s the only Python that I sense was an acidhead, and he was an American.) Compare the comedy people of five years later–like the Firesign Theater–and it’s ALL drug humor.

I’m sure Pete smoked his share of weed, and maybe took an upper here and there given his era, but he was a booze man through and through. Ironically, the course of Cook’s life would’ve probably been changed utterly by LSD therapy at the hands of Humphry Osmond.

American beatlepeople will remember this from the liner notes of Capitol’s “Meet The Beatles” and who am I to argue with that?

This may be too off-topic, but Drimble Wedge reminds me of the lead singer of the Zombies, especially when they performed “She’s Not There.”

Went back and watched the Zombies. I was wrong.