- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

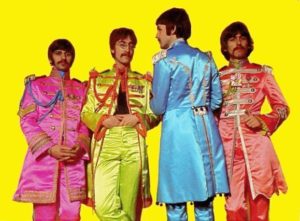

“Did you hear that, lads? It’s…HISTORY”

In a comment on Starostin’s latest review of Sgt. Pepper, Dullblogger Karen wrote the following:

Part of the charm of this album, as it relates to the construction of an alternate reality, is that it was borne of out a felt need. It wasn’t just conceptual; it was an “only if” type of reaction to the group’s growing disenchantment with their own fame. No other group had ever done that, and with the exception of Prince (who changed his name a few times for the same reason) no-one else has done it since.

This joggled some rather meaty thoughts for me, so I wanted to break it out into its own post. I am typing them as fast as I can — I’m in final production — so if they don’t make sense, I’ll unpack more in the comments.

Pepper is a charming album, maybe the most charming album by anyone ever. I have found that people who don’t like Pepper are people who mistrust charm in general. This is why Lennon famously wanted White and Let It Be to be “honest” — that is, not charming. The group failed in this; stripping away their own charisma was the one trick the Beatles couldn’t pull off.

And I’d argue that Pepper is in fact honest — but it doesn’t deal in personal honesty, but something larger, a kind of cultural or societal honesty. With/Meet the Beatles is similarly blessed — it surfs the explosion of youth into teenaged freedom that was happening all over the West in 1963-64. But of the Beatles’ later catalog, only Abbey Road gets close to this, in its wistful celebrations of nature and love and group endeavor, as the hippies looked back with nostalgia and forward with trepidation. Let It Be and to some degree White (and even my beloved Magical Mystery Tour) replace this essentially sincere deep cultural honesty for hipness, faddishness. LIB strikes the roots-rock pose, White strikes a series of poses. Isn’t Pepper — like MMT — also a pose, the psychedelic pose?

Well, yes and no. Yes, it’s a pose, but unlike with MMT, the pose being struck tapped into much more than a passing fad. MMT was an expression of fashion, and at its core, psychedelia wasn’t just a shift in fashion — it was based on a change in brain chemistry caused by drugs. This made it an immensely powerful cultural force, and we’re still feeling the effects today. The mainstreaming of pot and LSD from 1959-67 is much more like a religious movement than a fashion moment, much more important than everybody growing long beards (1969) or men wearing eye makeup (1972) or putting a clothespin through your cheek (1976) or or or… If psychedelia was a religious movement, Pepper is the Lord’s Prayer.

Pepper isn’t really the Beatles pretending to be another group, that conceit falls away almost immediately, and that’s why people (including Lennon) dismissed the idea of it being a true concept album. And the group that’s performing on Pepper isn’t an olde-tyme band — it isn’t “the act you’ve known for all these years” — but the Beatles themselves, using the same instruments, in the same idiom as Revolver…only this time overtly switched-on, tuned-in, and (in Lennon’s case) dropped out.

If Pepper had really been about the Beatles’ “growing disenchantment with their own fame” (the pressure of touring, greed, the claustrophobia of fame, madness) Pepper would’ve been like “Dark Side of the Moon.” The fact that it wasn’t, shows that the identity-shift was a tool and a departure point; Pepper is more an augury than a realized concept album. And the fact that Pink Floyd’s album was about all those topics, suggests that the Beatles were the first, but far from the only, band to experience something that is almost impersonal. But the unholy drag of being part of a world-famous rock band isn’t, in the end, a very compelling topic. Pepper’s about something more, and much bigger, than the Beatles’ own experience.

Still, I think Karen is onto something with her point. The “felt need” at the moment was very sharp, and it wasn’t just being felt by John, Paul, George and Ringo — it was being felt by young people and eccentrics throughout the entire Western world. It was a desire for life to be better, more interesting, more colorful; for people to be kinder, more connected, more loving; for personal freedom, and freedom of expression. And it was a revulsion towards the cultures of death that ran the world. (Capitalism for one, the nuclear standoff for another.) It was a Utopian vision based on the physiological experience of unity/egolessness/boundary-lessness that are the hallmark of those particular hallucinogens.

One of these people has dropped acid and listened to Sgt. Pepper. One has not.

Pepper is the purest expression of the Utopian aspect of the psychedelic culture (with the possible exception of “All You Need Is Love”), and the music on it is full of optimism and yearning. It is this optimism, and yearning — both trademarks of McCartney — that made the album immediately recognized as a milestone throughout the West. And it’s the subsequent betrayal/rejection/dismissal of this Utopian dream that made people disown or dismiss Pepper, John Lennon particularly. Lennon never said anything shitty about Pepper until after India, when the Summer of Love had slumped into the Days of Rage. Suddenly, psychedelic inner-revolution based on love and assorted good vibes seemed naive at best, and suicidal at worst.

Pepper’s tapping into this larger cultural movement also explains why Paul McCartney couldn’t top it; he wrote a lot of great music, and used a lot of the same structural tricks to recreate the explosive nature of Pepper, but it never worked. (Band on The Run has always seemed to me to particularly suffer in comparison to Pepper.) But the genius of Pepper wasn’t about Paul; it was much bigger than that. Pepper was the young world’s response to a catalog of horrors that had been building for decades, probably since World War I, and certainly since Hiroshima. Paul was perfectly suited to translate this idea into music. Pepper was, and remains, a revelation — and a call to revolution.

I agree that Pepper feels Utopian, Mike. I spent a good bit of this last weekend participating in discussions of utopian and dystopian literary works (yes, I am EVEN MORE of a nerd than you thought), and I was struck by how much more convincing most dystopias are. “1984” is straight-up terrifying; Robert Owen’s “A New View of Society” is interesting, but pretty unconvincing.

But music can express the utopian impulse more convincingly, I think, because it appeals primarily to feelings and not to rational, logical thought. Pepper’s beauty — its melodies, textures, vocals, and moods — really does create an alternative reality for me for the length of time the record is spinning.

Utopian impulses are easy to mock, and one way people can feel wised-up is to say that those impulses are all foolish. All utopian plans have their flaws, but the impulse toward utopia is, IMO, one of the things that makes us human.

We live in a collective trance of unworthiness. For lots of good evolutionary reasons, we’re five times more sensitive to unpleasant experiences than pleasant ones; we feel this imbalance and call it reality — when it’s not.

“Utopia” isn’t quite the word for what I’m describing; closer to it is simply “better than what we have.” Like, Beatlefest but better. What you ate for breakfast, only delicious. Perfection is, once again, our brain bleating at us.

The songs may be better on Revolver, the band more cohesive on Rubber Soul; but for pure alternate reality, nothing beats Sgt. Pepper. It’s simply a very pleasant place to be — even “A Day In the Life.” And that’s where Pepper succeeds where SMiLE failed. SMiLE is beautiful music, but only intermittently a pleasant place to be.

I think there ought to be a dullblog medal for joggling Mike’s meaty thoughts. 🙂

When I wrote that I was reminded of something Paul said about the origins of the Pepper concept–paraphrasing, but he essentially said that he was imagining an alternate non-Beatle hype reality in which the four of them could produce some music.

LOLOL!

Yes, I got that, @Karen, and I thought you had a point. I just went off in another direction with it.

Utopianism is a HUGE part of the post-touring Beatle idea; one of you added an image to the post — the Yellow Submarine — and that, too, is a product of this period. What would YS have been had it gone into production even six months earlier? Or later? It endures, particularly among the young, precisely because of this symbolic, utopian aspect.

Children think of John, Paul, George, and Ringo as peers. The optimism, bright colors, and sense of freedom of the 1966-67 is a large reason why.

🙂

…And in total consensus about the utopian concept apparent in MMT, Pepper, et. al. It also just occurred to me that this also fits with John’s intent to create an alternate Beatle reality/Utopia in Greece. I think their personal frustrations were coalescing with the prevailing youth movement of that period.

Yeah, and there’s a sense with the Beatles that because of the craziness of their life, they got to the “hey let’s all fuck off and live in a commune” phase a few years earlier than the kids who followed them.

I was the one who added the yellow submarine graphic, mostly because of the text “To Pepperland!”

I think it’s important that “Pepperland” is the name of the place in the movie “Yellow Submarine” that starts as a utopia, becomes a dystopia, and then becomes a utopia again.

I think it’s important that “Pepperland” is the name of the place in the movie “Yellow Submarine” that starts as a utopia, becomes a dystopia, and then becomes a utopia again.

Yes, of course. They knew what the LP was about.

[…] written about my love for Pepper many times before (probably most lucidly here), and Nancy has written nicely here. It’s not as though the album needs defenders. Or does […]

[…] as I’ve been alive. None of us know what the future holds – whether Pepper’s brand of “psychedelic utopianism” will be tried again, or people will attempt to reach a different kind of utopia a different way, or […]