- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

DEVIN McKINNEY • Warning—there’s a lot of rant here, most of it to do with Albert Goldman but some of it just my articulated flailings about the nature of biography and criticism, writers and readers. But Michael asked, I answered, this is our blog, and we make the rules. So strap on your poncho and feel free to skip around.

Reading the “Drugs and Differences” comments, I took special note when the ghost of Albert Goldman reared its shiny dome. He’s so easy to despise and so difficult to defend on any level, but I’m always curious about the case to be made in favor of things found by conventional wisdom to be irremediable. I also think Mike makes good points. (For one thing, I’d forgotten Bob Spitz used Goldman’s interviews in writing his book, which I thought was first-rate, probably the best single Beatles bio yet—amazing, since Spitz’s preceding biography, of Bob Dylan, which also thanked Goldman, was close to terrible.) Then, when Michael asked what I thought about Uncle Albert, I pulled out my Lives of John Lennon first edition (it might be worth something someday) and looked at the notes I took while reading it in the summer of 1988, for the first and (I’m quite certain) last time.

As a writer—more a critic than a biographer, but a critic who’s written at least one book that played by the rules of biography—I look at the book somewhat differently now. In 1988 I was 22 years old, a righteously pissed-off Lennon fan and Rolling Stone subscriber (Goldman had been preemptively attacked in an epic cover story). So my notes allow AG only a few positives. I highlight his factual errors and quarantine [with brackets] his frequent outbreaks of wretched style; where the text is inoffensive or passable, the margins are blank.

I still agree with most of my notes, but now find a number of them reactive, snarky, and unfair. For example, an early-pages observation: “G[oldman] accepts John’s self-analysis when it fits his own thesis, otherwise not.” What I see now is that anyone who wishes to reach a conclusion, favorable or unfavorable, slanted or equitable, will do that—biographers, critics, scientists. You start out, if you’re honest, by ingesting information and impression without preconception. But comes a time you have to go with your gut on what is true or false, sturdy or flimsy, what works and what doesn’t, what is the unwilling self-revelation versus the canny self-promotion. You have to venture any number of hunches about where your real story—i.e., your subject—is hiding. That means following certain avenues of inquiry and rejecting others; that means leaving out what you find to be unimportant, tangential, unproductively evasive, or simply false to the subject’s character as gleaned from your overall research. In a word, if you want a thematically shaped response to a subject’s life, you have to select—thereby leaving yourself open to charges like the one I made against Goldman in 1988.

The Lives of John Lennon is rich in factual errors (some listed below). I have more sympathy for biographers and their mistakes since learning for myself how easy it is for the stupidest, most obvious and confounding of errors to simply escape notice, even in the course of numerous drafts and countless hours of concentrated labor. I was fortunate enough to have a copy editor with an unbelievably keen eye, so 99% of the errors in my Henry Fonda biography were caught, many to my cringing embarrassment. But I know that others, as yet undetected (at least by me), and probably attributable to nothing but a momentary lapse of focus, managed to survive. We’re human, and that simply happens.

Goldman has a near-obsession with the subject of plagiarism, especially unconscious. “A whole book should be written about plagiarism in pop music,” he writes parenthetically in The Lives, “not only to expose the thieves and give belated credit to their victims but to illuminate the fascinating processes by which ideas are spawned and spread in the mental incubator.” This gives a sotto voce shout-out, as it were, to Goldman’s first book, The Mine and the Mint, all about the uncredited borrowings then-Professor Goldman dug up in the work of 19th century English memoirist and opium addict Thomas de Quincey. So I hopped with excited memory (or memoir) when I read, many pages later, Goldman’s description of a 1968 John and Yoko art installation where the entire contents of a room were cut in half. Goldman refers to the room’s putative “half-witted decorator”—and I said, wait a minute! Sure enough, I’d seen that joke before, in a contemporary London newspaper report on the show. See it quoted in Nicholas Shaffner, The Beatles Forever, p. 105.

But here too I have to give Goldman the benefit of my older and I hope wiser doubt. Unconscious plagiarism happens, conscious plagiarism happens, and if it amounts to a few words as in the above example, that means only that the writer had the sense to swipe a good line. Referring to the editing of Eat the Document, a D. A. Pennebaker-filmed record of his 1966 UK tour, Bob Dylan said he cut the film “fast on the eye.” Many years later, that exact phrase, which I have encountered nowhere else, turned up in an essay by Greil Marcus, Dylan’s most famous critic, about the best movies of the 1980s, in reference to Walter Hill’s editing style in 48 Hrs. So what. It’s intertext, interchange, intercourse, and when confined to a few words it’s mostly okay. Closer to home: a sentence in my third paragraph above—about a critical study “playing by the rules of biography”—is a not-so-unconscious lift of a near-identical line in the first chapter of Norman Mailer’s “novel biography” of Marilyn Monroe.

Similarly, I now grant Goldman the license to do certain things, make certain surmises, cross certain lines that others, both writers and readers, honor to the point of sacrosanctity. This may be mainly because I, unlike many people, take it for granted that biography is simply another form of creative writing. All writing is creative, since writing literally creates something that wasn’t there before those words were structured in that way, to that purpose. (Is it good writing? Totally different question.) But obviously it’s trickier in biography, because a) you’re writing about a real person, not a fictional character; b) the people most inclined to read what you write about that person are also likely to have the intensest personal investment in seeing them depicted in a certain way; and c) what no one realizes until they try to write a biography is that the biographer has, in every sense, to create his subject. That act of authorial creation, the passing of blood between the author and his or her absent obsession, is what makes the subject come alive for the author—and what should be needless to say, the subject has to live first in the author’s mind before he can live for a reader.

What fact-mongers and the terminally literal-minded never understand is that facts alone will not bring a subject alive. To pretend that a biography is, or should be, nothing but a data dump, free of opinion, point of view, personal prejudice, or creative temperament, is to willfully ignore how human minds work—let alone the very things that tend to make a biographical subject important to us. The biographer is not a mommy bird gathering, chewing, dissolving, and regurgitating fact food for direct deposit into the open throats of her blind, squealing babies. For a biographer to pretend to that role is insulting. For readers to ask so little credit for being sentient, processing beings is stupefying. Yet many readers claim to want just that.

Facts can take you up to the surface of the subject’s skin. You need them to even find where the skin is. But you don’t stop there, because you’re stopping at the level that anyone can see. You’re stopping at the OBVIOUS, and it’s not the job of creative writing to stop at the OBVIOUS, and merely confirm our mythological Average Reader in his or her preexisting opinions. To get any deeper, to venture near the hidden parts of genius or insanity, beauty or murder, where the prize of the NOT OBVIOUS waits, you have to allow yourself license and latitude. Using fact, informed opinion, the evidence of the subject’s work and the public record, and finally your own intuition, you have to decide what comprises your subject’s character, values, patterns of good and bad behavior, weaknesses and strengths. You have to grant yourself the license to indulge in some amateur psychologizing—provided you accept (as many readers of biography seem not to) that psychology is a real thing, and a determinant in human affairs. You have to form valid opinions based on clinical research, and remain ever skeptical of your own BS, making sure your psychobabble hews as closely as possible to contemporary DSM authority and is not just whiffed out of some poetic ether, or a teenage reading of Sybil. (Goldman would fail this test.)

At each point, you have to monitor your biographical creation for human plausibility, adherence to evidence, and thematic consistency—while holding in mind as you write each sentence that human beings can be and are radically implausible, defiant of evidence, and comically inconsistent. Even then, you’re not guaranteed that anything—least of all aesthetic and financial success—will come of your having lived in these varied states of pretzel logic for however many years you’ve foolishly devoted to the enterprise. But you have to take that chance to accomplish anything other than a waste of trees.

I have to acknowledge that Goldman—along with biographers I admire, from Janet Malcolm to David Thomson to Nick Tosches—begins from the premises described, and advocated, above. What distinguishes him, if that’s the word, is that he takes his license and latitude to such implausible extremes, going beyond a defensible use of defensible premises through a combination of arrogance, ineptitude, morbid compulsion, and really tortuous rationalizing. From my notes:

First, the pros, since they are relatively few. The main gain for me, as for Mike, is the background on Yoko, which simply didn’t exist at that time and to my knowledge still doesn’t. It amazes me that no one has yet completed (or even attempted?) a serious, comprehensive biography of one of the later 20th century’s best-known, most controversial, most well-connected and self-defined women. But when they do, Goldman’s research will be the foundation. (This is comparable to the investigative work AG and his stringers did on Colonel Tom Parker for the Elvis biography—also a case of a hate-filled book with an undeniable wealth of hidden history.) More generally, I felt there was a very nice, gritty sense of Liverpool given in the “Artist as a Young Punk” and “Mersey Beat” chapters, both of which moved well and were powered by precise imagery. Goldman can write well when he wants to (his Lenny Bruce biography has an incredibly vital sense of place, event, explosion, stagnation), but he so seldom wants to.

There are also good observations sprinkled throughout the book. “The Beatles’ primary achievement was to lift American pops [sic] off its foundations and transport it to England, where they transformed it into another music entirely.” True, that “transformed . . . entirely”; obvious, but true. And much later on: “Though John extolled spontaneous composition, adoring those songs like ‘Across the Universe’ that were ‘given’ to him, his best work was usually the product of slow, accretive gestation.” A point which is not only true but seldom made.

On to the cons. They call for bullet lists:

Self-puffery

— Goldman calls Two Virgins a “soiled air filter” of an album. He’s not wrong, but the point is that he then extols himself (in the third person) for testifying in court against the banning of the nude cover—despite having already testified (to us) that the record had no redeeming social value.

— Goldman lists his own interview with Lennon for a publication called Charlie (June and July 1971) as one of Lennon’s “major statements” on “his own character and history” (two of the others being the Rolling Stone and Playboy interviews). I’ve tried to locate this interview and haven’t found it reprinted anywhere. No Lennon source that I am aware of quotes it. According to p. xxii of The Lennon Companion, the entire interview comprised eight pages.

Poetic license to kill

— John hears Elvis for the first time: “Never has a writer or performer received a more powerful and compelling summons to his profession.”

— John had dyslexia, “a common neurological complaint”—and coincidentally the trendiest celebrity disorder of the late ’80s.

— Hearing “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” for the first time, Phil Spector shouts, “That’s a direct steal from my 1961 hit with the Paris Sisters, ‘I Love How You Love Me’!” That’s not human speech, that’s uninspired rock writing!

— “Perhaps [John] would complain of sexual deprivation, demanding that if [Yoko] didn’t want to fuck him, she should at least provide suitable substitutes, like some nice young girls—or boys!” Why not!

— Goldman imagines John indulging his Caligulan lusts in “a Korean brothel on 23rd Street,” without any “danger that these illiterate foreign prostitutes would create a scandal by, as Yoko put it, ‘writing a book.’” Perverse how the absence of testimony is tendered as a form of truthiness. Perverse as well how Goldman cannot resist picturing his subject in lurid sexual situations.

— “Alexa Grace looked at twenty-five like the young Ingrid Bergman of For Whom the Bell Tolls. . . . she had the shy, withdrawn personality of Laura in The Glass Menagerie.” It’s not horrific to apply two film or literary references to a single person—but in the space of two sentences?

— On a late ‘70s trip to the Far East, “John might have also indulged himself with a Thai boy . . . it is likely he had a nice long layout in the cathouses of Bangkok.” Yet later on in Tokyo, John, living “like a turtle”—withdrawn, in a shell—is said to be “indifferent to the garish pop culture of Japan, the ‘floating world’ of geisha girls, the porn shows…” Damned if you do fuck a teenaged prostitute, damned if you don’t.

— Defending Dakota-era aide-de-camp Fred Seaman’s thefts of machinery, tapes, journals: “It is characteristic of many rich people to conspire with their retainers to be cheated rather than to confront their true indebtedness to these invaluable people by paying them what they deserve.” That is sophistry for the ages. It’s at least as characteristic of many skulking functionaries to feel they have been shafted by the star-employers they pretend to worship and serve, and to get their revenge by stealing and selling the scraps of private life with which they’ve been entrusted. Seaman is a chief AG informant on the Dakota years.

Errors of fact

— What G calls “John’s most celebrated exchange with the press” was actually a Ringo scene in A Hard Day’s Night (“I’m a mocker”). Ironic that this piece of fiction got into AG’s memory as real-life speech, since he goes on to denigrate the Beatles’ first film in the harshest terms.

— “I’m All Shook Up” (Elvis’s “All Shook Up”)

— “Mary Lou” (Ricky Nelson’s “Hello Mary Lou”)

— Moon Dogs (Johnny and the Moondogs)

— “Hello Little Girl” was John’s song, not Paul’s.

— Ronnie and the Ronettes (The Ronettes)

— “I Want to Be Your Man” (“I Wanna Be Your Man”)

— “(We All Live in a) Yellow Submarine”

— AG calls “Any Time at All” “the most exciting song in the Beatles’ first film score.” It wasn’t part of the film score.

— “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love A-way” (probably a typo, but bad proofreading abounds)

— “(Baby, You Can) Drive My Car”

— “Drive My Car” is Paul’s song, not John’s.

— “She Said She Said” is given as merely “She Said” (so he’s half-right).

— There are no “hoedown fiddles” on “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

— Maharishi is not on the Sgt. Pepper cover.

— “One After 9:09.” The title refers to the train number, not the time of day.

— The Ruttles

— The Rutles was not a Monty Python project.

— John and Paul’s songwriting company was Maclen, not Lenmac.

— All Things Must Pass was released as three LPs, not four.

— “A. J. Webberman” should be A. J. Weberman. The once-notorious “Dylanologist” (known for scouring Dylan’s Greenwich Village garbage cans for proof of … something) is also one of AG’s chief sources on Lennon’s radical chic period. Which doesn’t save him from being misspelled.

— The 1978 Bee Gees/Peter Frampton musical Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is referred to as “the Beatles’ film.” The Beatles, of course, had nothing to do with it.

— Bob Dylan’s “You Gotta Serve Somebody” (“Gotta Serve Somebody”)

— “Serve Yerself!” (John’s “Serve Yourself”)

— “Nobody Told Me There’d Be Days Like This” (“Nobody Told Me”)

— “Bob Ezra” should be Bob Ezrin. Famed whiz-kid producer of Lou Reed, Kiss, Pink Floyd, many others.

Goldman, unlike myself, clearly did not have the services of a good copy-editor/fact-checker—or maybe even a bad one, from the evidence. William Morrow, a major publishing house with a stellar reputation, seems to have abrogated all editorial responsibility for this project.

Crimes against style

— “Before he heard ‘Heartbreak Hotel,’ John Lennon was a Nowhere Boy.”

— John meeting Paul: “a meeting destined to influence the whole future course of pop music.”

— Lennon “presents himself in song exactly as he did in life: as a hard case with a demand on his lips and a threat in his throat … [He] will do whatever it takes to get that little girl out there on the hook where she can cop the cash he craves. There’s no sexual heat in this guy and no congregational fervor around him. He’s a mack man, lean and mean, with a voice like a knife made of cold-rolled steel.” Mickey Spillane lives! But why here?

— Goldman insists on the weirdly outdated plural “pops,” as in “pops music.” So old-fogey, it’s like a whiff of mentholatum every few pages.

— Exclamation points are out of control!

o “John catches her in the act! … threatens to set her hair afire!”

o “So Freddie took off with John, intending never to return!”

o “He had become Beatle John!”

o “…upholstery!”

o “…the Dutch!”

— His slang is wack, yo!

o “rap”

o “youthquake”

o “to the max”

Unsupported, self-contradicted “sellout” theme

— The Beatles were ruined by “the emasculating hand of Brian Epstein.” This is part of a larger antipathy toward Epstein (“spoiled rich kid”; “Nobody in the history of show business ever took such a screwing” as did the Beatles by their manager).

— “Lennon succumbed to the enticements of commercial success. Rather than work to bring the public around to his vision, he adapted himself to the tastes of the mass audience.” Goldman never comes closer than the Spillanian pimp fantasy to telling us what he thinks Lennon’s lost vision was, or would/should have been.

— “‘Selling Out’ is the missing chapter in the history of the Beatles. It’s the chapter that nobody has ever wanted to write.” Including Goldman, who says the words but never writes the chapter.

— “By going commercial, the Beatles had reduced themselves to a formula.” But then this, a couple of chapters later, on Revolver: “The eclecticism of the Beatles, always one of their most striking features, explodes here in a dazzling display of artistic diversity.” So they sold out to what—eclecticism, explosion, dazzle, artistic diversity? Fine! The world has enough knife-wielding pimps.

Finally, for the best part-by-part disassemblage of Goldman’s shoddy craftsmanship and sleazy techniques, see Luc Sante’s multi-Beatle book roundup from the New York Review of Books. Luc is a friend, but I think he’d appreciate the irony if I point out that in his essay’s very last line, he, like Goldman, mistakes a line from A Hard Day’s Night for a real-life exchange. See what I said—mistakes will always slip through.

Devin, I love this post so much Albert Goldman could spin it into a lurid tale of infidelity. THANK YOU,

The question is: all these errors of fact and editing and good taste aside, do you think AG gets John right? If not wholly, what part? If not at all, where do you think he goes wrong?

One of your quotes reminds me precisely why I found the book so compelling: “…Korean brothel on 23rd St.”

1) That sounds like clumsily integrated interview material, eg,

“They weren’t having sex? How did that work?”

“John used to go to a brothel on 23rd.”

“Why that one in particular, do you think?”

“It was Korean, and the prostitutes there were undocumented and illiterate, so they could never talk…You know, write a book ‘I Fucked John Lennon.’ Yoko was paranoid about that.”

I know I’m making that all up, but that’s what happens in my brain when I read that sentence, and probably why I give Goldman so much more slack than others do. Norman did that a bit for me with Shout! but that’s it.

The only place I’d part ways with you, Devin, is the part where you talk about stars and their underlings. Maybe your experience has been different, but I’ve gotten to know a lot of assistants serving bigwigs at every level of the showbiz food chain (names not available upon request), and I’ve been utterly appalled at how shittily the underlings usually get treated. There’s a great novel to be written about the weird dependency and resentment that passes from star to assistant and back again; but in a purely economic light, it’s closest to slavery. In exchange to proximity to greatness and perhaps opportunity, the star has everything but the assistant’s very life in his/her hands–assistants can be fired at a whim, accused of theft, prevented from ever working in showbiz again, all with a single phone call. I’ve had friends who’ve been fired by their (revered in the press) bosses for getting cancer, not sleeping with their boss, being too old, and so forth. Does the assistant have some power over the star? Yes, if they are truly Machiavellian, but most assistants I’ve met genuinely admired the person and were devastated by what happened. If the star is a jerk (as so many seem to become it’s clearly the state of wealth and fame, not the people) the assistant will get screwed, somehow, before the relationship is through. Probably as punishment for the star’s dependence? Ya got me–but have a little compassion for Fred Seaman, and think twice before you believe Yoko’s side of that story.

Starpower also explains why there hasn’t been a Yoko bio, and likely won’t be one, ever. There is NO financial benefit for a book publisher in that project, unless it’s an authorized (or Norman-esque might-as-well-be authorized) bio. Anything that departs from the party line will be sued; and because Yoko is such a polarizing figure, the only people who would buy a Yoko bio are Yoko fans, ie people who don’t WANT to hear anything but hagiography. Which is a shame, because she’s a pretty fascinating gal. (That’s right, I called Yoko Ono a “gal.”)

Goldman’s book is a hit-job, but it’s a testament to how immense a figure Lennon was in our culture in 1988; 1200 interviews costs money! To me, The Lives of John Lennon isn’t really a music bio–it’s closer to the anti-Clinton or anti-Hillary (or anti-Bush) books that are printed. I judge it on that curve, and see it as proof positive that Lennon was, after 1968, primarily a political figure, not a musical one.

Devin, never have I laughed so hard while reading something so trenchant. Absolutely great.

I agree that every biography worth reading takes an interpretive stance, and that that inevitably involves selection and emphasis. In fact, I think strong emotional engagement, even where obsessive/negative, tends to produce a biography of more value than one in which the writer is disengaged or dismissive of his/her subject. Negative obsession produces more heat than light (e.g. Goldman), but lack of real connection produces neither.

God, I’d forgotten that Goldman said of Lennon in performance that “There’s no sexual heat in this guy and no congregational fervor around him. ” Now, that is plainly insane.

@Mike, on any bios of Yoko, even if books that departed from the party line would generate lawsuits, wouldn’t the authors win unless they’d made false statements of provable fact? I sure hope so, given the 1st amendment. Though I can see how the specter of such lawsuits might keep publishers from being willing to list such a biography.

This comment has been removed by the author.

@Nancy, it doesn’t matter if you win. Defending yourself in court would be so costly, and so drawn out, that any possible profits from such a book would be eaten up. Plus, you’d lose any chance to bid on future Beatle-related projects.

Also, I wanted to add: I just realized I don’t think of Goldman as a biographer. I think of him as something much closer to Hunter S. Thompson.

“One of your quotes reminds me precisely why I found the book so compelling: ‘…Korean brothel on 23rd St.’ “

That’s what I thought, too, and that’s why I’m persuaded that this book is worth reading (and, to that end, I plan to pick it up).

I feel that, with Philip Norman’s book, there’s at least a decent biography of John Lennon up to 1965. With Yoko still alive and litigious, it’s hard to imagine we’ll get an exhaustive, psychologically plausible, unwhitewashed account of the last fifteen years of his life, though, which is really sad, because that’s the most fascinating and, in a sense, almost tragic part of his life. Julia getting run over by a car was tragic in a personal sense, for Lennon, but the story of someone achieving everything they ever wanted, feeling more lost than ever, and careening from false solution to false solution until they begin to whither and withdraw, out of touch with their talents, out of touch with their friends. I want to read a book that answers whether, like I suspect he was, Lennon was voluntarily trapped in that relationship the way he was trapped in the Dakota, behind that impenetrable façade. I want to read this not because, like Goldman, I want to see him fail and fall, but because, as Michael’s often pointed out, that’s what makes him human and empathetic. To know that Lennon struggled with neuroses or anxiety or depression is much more relevant to most people than knowing he was tripping on LSD a lot. To know that he needed to mend fences that he couldn’t bring himself to mend is a much more important story than “he didn’t touch his guitar for five years.”

And it uncovers an additional layer of his psyche if, all the time he was being so open and honest with the media, he was actually keeping them at a distance and dissembling as much or more than his famously guarded contemporaries like Dylan, McCartney, or Jagger.

-Michael

*I never finished a thought there: Julia’s death was personally tragic for Lennon, but his last decade or so could arguably be seen as “tragic” in the classical sense.

Thanks, Mike and Nancy. Mike, this may not be what you mean by “does Goldman get him right,” but surely there is no objective, essential, unitary Lennon out there to be gotten right by any single biographer. Goldman gets pieces of him, as Coleman and Riley get pieces. Goldman gets the drugged-out, empty-eyed sensation seeker and ego machine Lennon probably was for hours, days, months at a time, maybe for an entire year here or there. But one can be right on the pieces while creating a larger picture that departs from reality.

Finishing the book, I felt I’d been in close quarters not with a person but with a hulking, shadowy monster. Since Goldman doesn’t really credit Lennon’s genius or his achievements except in glancing praises that are contradicted on every other page, it is the ogrish mediocrity that emerges, not the tortured, often self-centered artist. Instead of leaving me shaken because it brought up hundreds of hints and suggestions and resonances with words and images and feelings I’d absorbed from years of Beatle study without knowing it, the Goldman portrait left me alienated because it resonated so little.

So no, I don’t think he gets him right. I find it very easy to believe that John was muffled and stunted by drugs, self-indulgence, Yoko, his own laziness and fear. What Goldman constructs from these eventualities is not a melancholy portrait of creative and existential decline but a one-dimensional nightmare, lurching and laborious, about a non-person who is at once peripatetic and barely functional. On the levels of psychology, literature, and what I call “human plausibility,” the book is simply foolish.

That doesn’t mean it lacks all value, as I said. But it does mean that if Goldman gets those pieces of Lennon, he gets them only while executing an authorial agenda that leads him to seek out every noxious or unfortunate incident in Lennon’s life and then magnify the sum until it becomes the whole equation. But I would never suggest anyone not read, or fight through, the book. For its undeniable coups of research, its ill fame and controversy, and its extremity of approach, it is for better or worse one of the essential books about the Beatles, and anyone who cares about them, not to mention Lennon in particular, ought to read it.

Devin, I agree that no one biography gets all of Lennon, or could. I think the value of Goldman’s book, besides its original research, lies in its being written while memories of Lennon’s life were relatively fresh, and its not being in thrall to the view of Lennon the estate wished to promulgate.

If the Revised Standard Version of Lennon’s life hadn’t been so heavily promoted by 1988, and if that narrative weren’t still pretty dominant, there wouldn’t be a need for Goldman’s book. Goldman gets so much so wrong, but precisely because he’s fascinated by the dark side of Lennon’s life, he uncovers aspects the official line didn’t — and still doesn’t — want to acknowledge. The last five years of Lennon’s life, in particular, don’t make much sense unless we grapple with the things Goldman, Seaman, Pang, et. al. have to say. So I’m agreeing with you and with Michael (I think) that the Yoko background, and the access to Lennon’s life at the Dakota, are things that Goldman gets at least partly right.

IMO the Lennon estate and journalism like Rolling Stone’s created the need for such a book by relentlessly promoting a version of John Lennon with all the darkness airbrushed out. Goldman sure does tend to take “every noxious or unfortunate incident in Lennon’s life and then magnify the sum until it becomes the whole equation.” Those incidents are very far from the whole equation, but they are part of it, and a part of it that, at least for a long time, was denied or overlooked.

The crazy thing is, as many on this blog have said, that LENNON DOESN’T NEED MYTHOLOGIZING. What he actually achieved, who he actually was, is plenty. I find the estate’s hostility toward treatments of Lennon that don’t toe the party line completely (for example, Norman’s bio) both unnecessary and deeply ironic, given that one of Lennon’s most profound statements is “one thing I can tell you is you got to be free.”

On the other point, Mike, about rich people and their servants, I don’t know anything about those imbroglios beyond what I sometimes see in the news. And without doubt there’s some truth in Seaman’s various testimonies. But that vagary and other celebrity situations aside, Goldman errs in going out of his way to make such a convoluted and hypothetical defense of a felonious informant. (Seaman has always protested his innocence, but a judge found him guilty.) He’d have been smarter to acknowledge the worst that might be said of Seaman, then argue for the validity of the information anyway. Instead he uses Seaman’s perfidy as another source of innuendo by which to club John and Yoko. That’s just rancid journalism.

Like all others in his position, in the US anyway, Fred Seaman wasn’t an indentured servant; he could have left the Lennons’ employ at any time. Instead he stayed, took their abuse and threw out their diapers for low pay while pretending fealty, and then, at the most loathsome conceivable time, stole their stuff and tried to sell it. Assign credibility accordingly.

I’d have more respect for Seaman if he’d simply written a tell-all book. Oh wait, he did that too. Most recently, he made yet another mini-splash for himself by claiming all over the blogosphere that Lennon had turned into a “closet Republican” before his death. When your revelations all tend to run one way, toward the grim and idol-smashing, I wonder more about the psyche of the smasher than the idol.

You’re absolutely right, Nancy, that a value of the Goldman book is that it gets a lot of things into the record that might have slipped through cracks in time. And I can’t agree more about the need for some corrective to the tiresome goddamned Standard Version as propagated by Yoko Ono Inc., Jann Wenner, CEO.

Obviously, one wishes the corrective had come in some other, less distorted form. Goldman jarred a lot of complacencies, but by going to such an opposite extreme he did nothing but create the need for yet another kind of corrective.

So it will ever be with a figure like Lennon. Biogs will continue to be written because there’s always some “new” angle that cries out to be taken–or so publishers and readers will always be led to believe. I’ve not read the Norman biography; that’s a gap I need to fill. I would count the Coleman bio as virtually negligible were it not for the odd insights afforded by his insider status (London, sixties, close to Epstein), though this very insiderness engenders numerous blind spots (his hysterical denunciations of the Lennon-Epstein Spanish sexcapade being merely the most memorable). Also, it’s not clear to me how much Coleman cares about the music.

Tim Riley’s biography is probably the least inside, and close to being the least sensational, that exists, but of the ones I’ve read, it’s easily the best–sympathetic but not slavish, skeptical but not snarky, musically passionate and historically informed, with a lot of novel research. (He acknowledges my book, but that has nothing to do with it!)

@Devin,

“What Goldman constructs from these eventualities is not a melancholy portrait of creative and existential decline but a one-dimensional nightmare, lurching and laborious, about a non-person who is at once peripatetic and barely functional.”

This, and the rest of your summation, is the best statement on Goldman I’ve ever read. Just superb. Thank you.

@Nancy,

“I think the value of Goldman’s book, besides its original research, lies in its being written while memories of Lennon’s life were relatively fresh, and its not being in thrall to the view of Lennon the estate wished to promulgate.”

This is HUGE, and we Dullbloggers tend to forget just how huge. For everybody who reads this site, there was something about The Beatles that struck a chord. For myself, if the only portrait of John Lennon available was the Yoko-approved one–ie, the person you see in the “Imagine” movie–my affection for the man would’ve moved on very quickly. Because you know what? It’s boring, and feels false. It’s Lennon as a corporate brand, and that’s particularly offensive because the “Lennon brand” is supposedly based on searing honesty and openness and acceptance–yet the story they insist upon is none of those things. It’s as controlled, bogus and manipulative as the backstory to a frozen dinner. “We only pick the ripest, freshest tomatoes…” In that context, Goldman’s a fucking godsend precisely BECAUSE he’s a loathsome bottom-feeder. People who need John Lennon to be St. John are either (1) making money off that, or (2) missing the only reason John Lennon is any more notable than, say, Justin Timberlake.

@Devin,

John Lennon may well have preferred Reagan in 1980, but that shouldn’t be as shocking as it seems. People were really freaking out about Carter–inflation was the only thing that could’ve pauperized John, and it was at 20%. He had a terrible fear of “ending up in Vegas”–and that’s why they were buying cows and real estate in the late 70s. Plus, we didn’t know what Reagan was then; IIRC, the RKO interview has him being fairly blase about Reagan’s election, and all interviews show his greedy side. Do I think John Lennon would’ve been on Reagan’s side in the culture war (which is obviously what this is about)? No. Absolutely not. Not ever.

I’m not here to defend Fred Seaman, just to counsel caution. Nobody but him knows what John Lennon said to him, and those diaries were a basic threat to the branding the estate was trying to do. So the estate acted like any corporation would: sued him to get the material back, and smeared him via friendly news outlets. Maybe Seaman deserved it, but the fact is, the moment the “disgruntled employee” meme gets traction, it’s over. On one side, there’s immense piles of money and love of a dead celebrity and respect for his widow, and on the other, there’s a guy we’ve never heard of wanting to get rich.

The estate is a corporation and should be viewed as such, and unlike the Harrison estate for example, or MPL, seems to always be doing stuff that courts controversy. Like licensing Lennon for cheesy stuff, or in a messy lawsuit, or defending its rights in a paranoid way, or aggressively accumulating all Lennon-related IP, or… Do corporations do this all the time? Yes. Does it seem at odds with the brand they’re trying to defend, and the progressive politics of the owner? Yes. I think she’s getting bad advice. People love John Lennon, and his estate–and the widow running it–could be viewed as a real force for good, if it could just stay out of court and be a little…nicer.

But currently, I don’t trust the estate to be truthful when it doesn’t suit them to be truthful, and especially given the stakes–a bunch of diaries that (apparently) damage the brand–I don’t trust their version of events any more than I do Fred Seaman’s. I don’t think anybody came out of that looking good, and it’s a shame because nothing I’ve ever read from Seaman’s source is all that shocking.

Sometime when you come out here again, I’ll tell you some stories about stars and their assistants, and I think you’ll see where I’m coming from. Are there devious and conniving assistants? Absolutely. But my experience, which may not be representative, suggests that stars are *encouraged* to act like monsters. A devious assistant is, it seems to me, a bad apple; a monstrous star is a product of a whole monstrous star-culture.

Thanks, Devin, for saying the following:

“[T]he biographer has, in every sense, to create his subject. That act of authorial creation, the passing of blood between the author and his or her absent obsession, is what makes the subject come alive for the author—and needless to say, the subject has to live first in the author’s mind before he can live for a reader.”

Reading this helped me understand why I disliked two particular biographies: Truffaut: A Biography, by Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana; and Various Positions: A Life of Leonard Cohen, by Ira Nadel. Both are lifeless and plodding, precisely because the authors refused to marshal their own imaginations to the task of bringing their subjects to life. (I’m a history teacher, and I would have to say the paradoxical-sounding thing that writing history [as well as biography] requires not just command of the facts, but rich, worldly *imagination*.)

By the way, I’m a huge fan of Magic Circles. Here’s a book that wins the reader over to what the author has figured out not only from exhaustive consideration of the material, but also from deeply insightful imagination.

Thank you, Mudarra. That’s very nice to hear.

I must confess I’ve always loved Albert Goldman’s prose. When I was a college freshman back in 1977, I bought his Lenny Bruce biography and fell in love with it. Some fierce and outrageous paragraphs, real word jazz, especially when he describes 1950s America. I loved his savage biography of Elvis; it’s laugh out loud funny. Parts of it reads like standup comedy. I remember reading his Lennon book when it was serialized in People magazine (of all places). Again, a savage cat scratch of a book, but I loved how he uncovered the early days of Yoko and Cox. Some of what he writes about Lennon, and about Lenny, and about Elvis turns out to be bullshit, but it’s such audacious and inspired bullshit, I couldn’t help but be carried along with it.

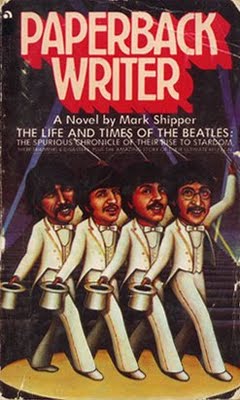

Looking back, I now see that he follows the same template with all his bios: The subject begins his career fueled with amphetamines, turning accepted art forms upside down, stealing from others and creating something new. The subject is sporadically brilliant, but he soon betrays his creativity by churning out garbage ( in Lenny’s case, his rants on the law, in Elvis’s case, the movie music, in Lennon’s case, his inferior Beatles and solo work). After burning out, the subject isolates himself and slowly self-destructs. This is the EXACT same template in all three of Goldman’s bios.

– Hologram Sam

Looking back, I now see that he follows the same template with all his bios: The subject begins his career fueled with amphetamines, turning accepted art forms upside down, stealing from others and creating something new. The subject is sporadically brilliant, but he soon betrays his creativity by churning out garbage ( in Lenny’s case, his rants on the law, in Elvis’s case, the movie music, in Lennon’s case, his inferior Beatles and solo work). After burning out, the subject isolates himself and slowly self-destructs. This is the EXACT same template in all three of Goldman’s bios.

From what I understand, Goldman was working on a Jim Morrison biography but never lived to finish it. I have no doubt the Morrison bio would have followed this exact template.

…which begs the question: was Goldman onto something with this?

Only in Lennon’s case could one argue that Goldman’s being unfair; Bruce was utterly spent as a force in comedy after 1962 or so. By 1966, he was actively turning away from a world that had caught up to him and was practically begging for his input again. Elvis’ movie years were utterly lost creative time, and with the exception of the 1968 comeback, he was completely spent.

It’s not Albert Goldman’s fault that Bruce, Elvis, and Lennon all followed the same pattern — he has to go where the life takes him — and heavy drug use early in the career is something all three shared. Were amphetamines responsible for much of the signal creativity of the postwar era? And if so, wouldn’t the predictable effects of that drug on the central nervous system — regardless of whose CNS it was — create a similar pattern in artist after artist?

Yes, you’re right. And I think Goldman chose his subjects because they followed that trajectory. Why? I don’t know. Something about this particular pattern fascinated Goldman enough to want to document it again and again. Maybe he feared his own life would take that path? Maybe by writing these unhappy-ending biographies he could ward off his own unhappy ending?

And how did Goldman end up? After decades of New Journalism he ends up being most famous as “that asshole who wrote those mean things about our John” rather than the great writer he wanted to be.

That’s a great question, Sam. It would be interesting to look at other authors of multiple biographies and see if they gravitate toward life stories that follow a particular pattern. (Or, in some cases, if they impose a particular pattern on whoever they write about.)

Your idea that Goldman might have been trying to ward off his own unhappy ending by writing as he did about his subjects seems plausible to me. Also sad, as you note, given the way his own story ended up. In general, the insight that we often deplore in others that which we fear recognizing in ourselves seems applicable here.

I’m not sure if I think this is about Albert Goldman. Case in point: quite randomly this weekend, I happened to pick up a biography in graphic novel format of the famous artist’s model, singer, and painter Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin). And her life too seems to be fitting this template — including the heavy drug use.

And just as I am typing, I note that Jack Kerouac‘s life fitted this same template.

It’s always easy to imagine Goldman there in the corner, twirling his metaphorical moustache; but to me the larger and more interesting question is: what happens when artistic genius collides with an era where x, y, and z drugs are commonly used by artists? Does a common pattern emerge? If so, where does individual choice end and neurology begin? And could this be what Goldman was trying to get at, with his life’s work? And if it were, shouldn’t this rehabilitate him, at least a little bit?

Goldman’s a jerk, no doubt; but is he a bigger jerk than all the biographers who’ve soft-pedaled John’s misbehavior? Why is that? Because we love John’s music? That seems off to me.

Way off topic here but I’m not sure where else to post it.

Jimmy Nicol’s story has always intrigued me and some writer has finally written his story. Wow, if you didn’t believe the Beatles were/are a huge story, what proves it more than an entire book being written on a guy who randomly played in the band for 2 weeks and then was never heard from again. I doubt I’ll purchase the book but I’d love to stumble upon it in a library in ten years.

http://tinyurl.com/cwaqvuq

A nice piece of writing in two ways. Interesting points to learn for any student to become a writer/journalist. And I am now going to get me a copy of Goldman’s book – AGAIN.

Always wondered why Maureen Cleave’s mid 1966 depiction of Lennon hasn’t been granted more importance. It is a nice point of departure for a biographer. The very words she says about his attitude and life style resonates for me in his sleepwalker (not my phrase, but McDonald’s) balladeering. John may have been playing with words and styles, hiding etc. but that was all very authentic. And interesting from an artistic point of view. Lennon was no faker or poor sod, yeah was a lazy sod, who produced wonderful and fascinating music.

[…] the way, if you’re interested in Goldman, we’ve talked a lot about him here; this magisterial post by Devin is a good place to […]

Another error in the book is that ” I want to hold your hand” was primaty a McCartney composition not a 50/50 composition as Goldman says. He even contradicts himself when saying 50/50 as he Said Paul had the song title and melody. Truth is I want to hold your hand is primary a McCartney composition. The title he took from hus own song ” I wanna be your man” they sing wanna in the song but was considered bad English by publicity company. In Paul McCartneys handwritten song lyrics it says ” I wanna hold your hand” in McCartneys handwritten songlyrics it Also says ” I wanna hold your hand ” in the refrain.

The melody Paul took from his song ” Hold me tight” Paul wrote it on piano where he was very advanced in one hour in the Basement of Jane Ashers ( his girlfriend) families house. Paul the shouted to Peter Asher to come down and listen to the song. Peter Asher was the first one to hear it.

Say what? I don’t even think Paul himself has claimed that I Want to Hold Your Hand was anything but a 50/50 collaboration. He and John both described it as one of their nose-to-nose compositions. I Wanna Be Your Man was written by both as well, as they were in a room with Mick and Keith when they went off into a corner to compose it.

“In 1994, McCartney agreed with Lennon’s description of the circumstances surrounding the composition of “I Want to Hold Your Hand”, saying: “‘Eyeball to eyeball’ is a very good description of it. That’s exactly how it was. ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ was very co-written.” (Miles 1997, page 108)

All I can say is “Thank you.” I’ve been waiting since 1988 for someone to, line by line, point out the sheer tonnage of stupidity, conjecture and made-up “facts” in this “book” including “John and Brian had sex.” (I paraphrase) which is like declaring, flat out, “Brian Epstein played bass on “Think For Yourself.”

This man certainly had some problems. But like our (former) Orange President, I think Goldman got a perverse thrill out of being despised. Maybe he jerked off to being eviscerated.

Bottom line: If this guy can make a million off writing, anyone can.

Goldman had a few errors and a lot of negativity, but he also uncovered a lot that’s since proven to be less outlandish than I think people first believed when the book came out. Er, the John/Brian angle is actually one of the things Goldman had right, although the extent of their relationship has never been proven. As societal attitudes towards gayness change, I think there will be even more information that comes out.

If the extent of John and Brian’s relationship has never been proven, what exactly did Goldman get right? The part that is common knowledge, i.e. that Brian had a crush on John and took him on a paid trip to Spain? Or the parts that he invented (and until they are proven, that’s all it is).

Some of Goldman’s outlandish claims about John:

-He and Brian had a fully fledged homosexual affair

-Implied he would go to Thailand to hook up with under aged prostitutes

-Implied he also trolled for sex with under age boys in Manhattan gay clubs

-Implied he attacked and maybe killed a man in Hamburg

-Implied he had a direct part in Stu death

-He vivaciously beat Yoko because she had a miscarriage

– he avoided touching Sean

– he was anorexic

– he and Yoko were responsible for Paul’s Japan arrest

I don’t think those have been proven any less outlandish then when he first claimed them.

Goldman and three sources (Fred Seaman, Sam Green and John Green) said that Yoko, not John, engineered Paul’s Japan arrest. It’s not confirmed but it wasn’t disproved either.

Fred Seaman a man who was stealing from John and Yoko and had an axe to grind with Yoko because she fired him and had him arrested for stealing is hardly an unbias and credible source.

Sam Green, John and Yoko’s art dealer who had an affair with Yoko, was one of Goldman’s sources and also said Yoko arranged the bust. Yoko even amended John’s will to make Sam Sean’s legal guardian in case something happened to both John and Yoko.

I don’t think Goldman’s suggestion that John and Brian had an affair is comparable with pedophilia, murder, or spousal abuse.

Except he Goldman did imply that he was sleeping with underage prostitutes, and that he beat Yoko because she had a miscarriage. And that he played a part in Stus death.

@LeighAnn I’m aware of that but you putting John and Brian’s alleged affair in the same list as some of these actual crimes is implying it’s just as bad as them.

I don’t mean to imply anything. I’m just listing things Goldman wrote about like they were facts that he had no or little evidence to back up. And other then the fact that John and Brian went on holiday together and John describing an interest while in Spain with Brian’s lifestyle and how close they were- John called it a love affair that wasn’t sexual- we will never know the extent of their relationship and Goldman has no evidence to claim any differently.

Also Goldman made negative connotations by implying that John used sex with Brian to advance his standing in the Beatles, basically putting a tawdry twist on the accepted and likely view that John was trying to ingratiate himself with Brian by going to Spain.

For what it’s worth I don’t think someone as experimental or open as John would balk at being with a man or that it makes him less as a musician or his legacy if he had. I think it’s very possible.

But I also think there’s a tendency of fans and writers to take the sometimes intense, complex and intimate relationships that the Beatles and their immediate circle and assume there had to be something sexual there. John and Paul or John and Brian can’t just have loved one another without assumptions that they were “in love” with one another or secretly f@*king. John couldn’t have just wanted to go and enjoy a holiday with Brian without being gay himself.

If John and Paul were in love and secretly hooking up or Brian and John were in love and secretly hooking up there’s nothing wrong with that but if they weren’t in love and hooking up there’s a unfair prejudice and stigma to put on intimate close male relationships.

There is an important distinction between alleging an affair between a homosexual manager and his handsome star–a tale as old as showbiz, really–and one between two of the most famous collaborators of the 1960s. Brian and John having sex really mattered only to Brian and John, and perhaps the rest of the Beatles’ circle. John and Paul having sex would have been the showbiz scoop of the century.

I think it’s fair to assume that John and Brian loved each other very much. I think it’s fair to assume that John and Paul loved each other very much. But by the time of the Spain trip, Brian slept exclusively with men; and Lennon’s tale, while it changed, wasn’t “We never had sex.” If they didn’t have sex, it would’ve been simple to say, “We didn’t have sex.” Not “he tossed me off,” or “he blew me” or whatever. That all sounds like “a limited hangout,” as they say in the spy game.

To go on vacation with your gay manager, knowing full well he has a crush on you–it’s possible nothing happened, but not very likely. It’s more likely they had sex. Then add in Lennon’s sensitivity about it, and then his changing stories. I think they had sex, and by the time of John’s death, that was canon.

Goldman’s reading of the John/Brian relationship–that Brian fancied John, which is largely why he took a chance on an unknown group; and that John used Brian’s attraction to further his own interests–is based on a knowledge of how “the casting couch” usually worked. It might not have worked like this in this case, but it was common.It probably still is.

Goldman interviewed about 2000 people, Leigh Ann. Of course he had evidence to back up what he wrote.

What I find also very interesting is that all of the interviews are available to scholars at Columbia University. That’s a testament to Lennon’s importance as a cultural figure, and also Goldman’s importance as a writer. I have dealt with acquiring archivists at Yale and Columbia, and trust me, if there wasn’t real historical significance to that archive — if Goldman had just “gotten people drunk” — they wouldn’t have bought it, or keep it now.

Goldman got a lot of things wrong, and didn’t have the necessary sympathy for a first-rate biography. But his spade-work was essential, even if it didn’t unearth what we wanted it to.

I wouldn’t say all those things are spurious or invented by Goldman. For a few examples:

The story about Yoko’s involvement in Paul’s arrest had been in John Green’s book years before Goldman’s; and would also be recounted in Seaman’s book later. They only differ on Lennon’s reaction. Green has Lennon remorseful. Seaman has Lennon jubilant. Given the nature of Lennon’s moods, it isn’t impossible that both accounts are true.

Pauline Sutcliffe maintained until her death that Stu’s haemorrhage was the result of his being kicked by Lennon. She also says John and Stu had an affair.

The Brian/John thing had obviously been around for a long time. Hunter Davies said Lennon told him off the record that he and Brian had had a one-night stand. To Pete Shotton he [Lennon] said he let Brian toss him off. To Bob Wooler who made a quip about his relationship with Epstein, Lennon responded defensively by smashing his face in with a shovel. The story in Goldman’s book where Lennon and Epstein are almost caught in flagrante delicto by Queenie (in 1967, which if true, would imply an extended affair) comes from Marnie Hair who heard it from Yoko. Anecdotally, there is plenty to suggest a relationship between John and Brian. The nature and the extent should be the question.

Similarly, the story about Yoko’s miscarriage being caused by a beating was told to Arlene Reckson by Yoko. (There is some irony that a number of the accounts Yoko was obliged to deny when Goldman’s book was published seemingly originated from her in the first place.)

The anorexia is, at the least, not disproved by some of the emaciated photos of Lennon later in life; or by his staples of macrobiotics, heroin, and cocaine

The point is, that whatever the truth of the reality might be, and on many questions we may never know, Goldman did not exist in a pure vacuum of invention. His information came either from people he and his team interviewed; or information which had been previously available. The passage about Thailand is the only instance off hand I can think of where he falls into egregious speculation.

Fred Seaman plead guilty to stealing from Lennon, including reportedly on the night after learning he died, had plans to fabricate Lennon diaries to make it seem like John wanted him to have his personal belongings and admitted in court that he lied about Yoko and John in books and interviews.

Marnie Hair was basically trying to extort Yoko and tried suing her by claiming her nanny endangered her daughter.

John Green did not have a close relationship with John and by other accounts John didn’t really buy into Tarot as much as Yoko did.

Medical professionals have discredited the theory John killed Stu by kicking him in head years earlier by saying it’s medically inaccurate.

John was regularly seen out and about in restaurants in New York including famously the night he and Paul order pizza to a restaurant because they couldn’t find anything they liked on the menu, there was stories about how he loved cooking lunches in his later years for them and Jack Douglas said he would hide chocolates in the studio from Yoko so she wouldn’t know that he was breaking their macrobiotic diet, and there’s recordings of him from the Double Fantasy sessions asking for sushi. He hardly had an aversion to food that anorexic do.

The most ludicrous stories Goldman quoted are from the most unreliable sources who had personal axes to grind. While the people who actually loved John knew him on a personal and intimate level all say the book is nonsense. Even Cynthia who probably has every right to have her own greviences said the book was rubbish. Paul’s brother Mike said he was approached by Goldman’s researchers and picked up early on that they were only interested in the most negative stories about John and recalled how I think Paul’s first girlfriend Dot called him up crying saying how she felt she had been “mind raped” because they used interview tactics to twist her answers.

Look, if we’re going to play this game, we have to start with the most obvious one:

Yoko Ono moved in with her boyfriend the night after her husband’s murder. (Wow!) She continued to live at the scene of her husband’s murder. (Wow!) There are persistent rumors (and maybe more than that, I can’t be arsed as they say, to look it up in my books) that she had filed for divorce in 1974, and in 1979-80 was investigating it again. (Wow!)

We know that John and Yoko were living pretty separate lives by 1980. We know for sure that for at least 18 months out of their 11 years together, they were separated and seeing other people. We know that they were both strong-willed personalities with fierce tempers and competitive streaks. We know that Lennon was perhaps conflicted about having Yoko on DF, but she was determined to make it a collaboration. We know Yoko isolated John from a lot of his friends, including sometimes Paul. We know that John’s weight and health seems to have deteriorated in the years he was with Yoko. We know she introduced him to heroin.

Given all this, and even if we put her in the most charitable light, why on Earth should we believe Yoko’s version of anything relating to her ex-husband? Why is she more trustworthy on this topic than Seaman, or Hair, or Green? Or Paul or anybody? Doesn’t she have much more to gain by lying than anybody? Yes. Obviously she does.

I’m not saying she’s lying, but it frustrates me when commenters uncritically accept her version of events. If anybody has a powerful motivation to control the narrative, it’s Yoko. The benefits to her, and the capacity she has to do exactly this, are vastly greater than Seaman or Green or Goldman or anybody else.

Those sources all lack a certain amount of credibility. If John or Yoko had anything to do with Paul’s arrest, it was a collaboration with Paul. He had his huge supply of pot sitting right on top of the other items in his suitcase. Who does that? He must have known how strict the authorities in Japan are when it comes to that stuff. John is quoted as saying that it was Paul wanting people to think he was “still a bad boy.” He thought Paul did it on purpose. Which with his negligence kind of seems that way.

We simply can’t know if Yoko made a phone call. As usual, it comes down to the image one has of her in one’s mind.

@Michelle I recall Jack Douglas maybe, saying how he was talking to John about how he couldn’t believe how reckless Paul had been and John defended Paul by saying something along the lines of “Well he’s a Beatle, we are not supposed to be searched” Which I’ve always felt was Paul’s logic. How many airports did the Beatles go through with contraband and by sheer magnitude of their celebrity managed to not be checked by security.

Paul’s also speculated in recent years that he psychologically was trying to get caught to have an excuse to end The Wings.

I think one of the Lennon’s maids said that John was stressed out over the ordeal and glued to the television the whole time but how accurate that is I’m not sure. Though it seems in character for John to be worried for Paul in private but due to pride unwilling to show too much concern for him in public.

He hardly had an aversion to food that anorexic do.

.

Eating disorders are much more complicated than that. For one thing they can go into remission for periods of time. May Pang’s book is full of behavior from John that is absolutely textbook eating disorder symptoms.

A stray thought joggled by this comment thread:

To be honest, going to Thailand to sleep with male prostitutes is about the thousandth most objectionable thing Goldman says about Lennon, and anybody who fastens on that as particularly scandalous is kinda missing the point.

John Lennon was a ROCK STAR. He had more sex, with more people, than any of us normal folks can imagine. The sheer volume of coitus he engaged in after 1961 or so was surely heroic, and almost guarantees that he had every type of sex with every type of person.

If you can imagine it, it’s likely John Lennon did it, or something like it, and if that idea makes any Dullblog reader uncomfortable, I would encourage more reading about the Sixties, and Alfred Kinsey. The period between the Pill and AIDS was drenched in sex, and rock stars were having more of it than anybody else.

To understand the lives of the Beatles requires a kind of fearless untethering from conventional morality, and I’m sorry to say most people cannot do it.

A couple of admittedly more minor outrageous Goldman claims stick in my mind, perhaps because I never see them mentioned:

.

John was unable to see inside himself because he had poor eyesight. Before I read that, I didn’t know blind people are incapable of introspection.

.

John was unusually lacking in manual dexterity. I guess Bernard Purdie played rhythm guitar as well as drums.

Ha the introspection comment.

I also think the John didn’t like touching Sean and would only see him for an hour a day is another overlooked claim given the amount of photographic and video evidence of him holding, caring and spending time with Sean, and Julian in those later years as well.

This is akin to saying, “Ringo couldn’t have left the group during the White Album sessions because look at the Mad Day Out.”

I don’t know why anyone would make that observation. There is nothing contradictory about Ringo having a fight with his mates and Ringo loving his mates. But John having an aversion to holding Sean and pictures/footage of John holding Sean certainly is. Unless you think John’s whole life was an act, and it was Yoko who spent every day with Sean while John took care of business matters, which goes against type. Perhaps Goldman took Paul’s statement to Hunter Davies about John refusing to let him hold Sean and turned it into John himself not wanting to hold Sean.

Sean had a team of nannies, Michelle. That’s not to say John wasn’t around – obviously he was at home and not working for much of Sean’s early childhood – but I find it highly highly unlikely that he ‘spent every day’ with Sean.

Photographs don’t lie, that’s true – for the 30 seconds it takes to get a shot, at least. Do you honestly believe that the worst, most abusive parents in the world don’t have loving photographs of their children? I watched an interview with Tatum O’Neal recently. Looking at her childhood photographs, you would think she had the perfect father, but evidently he was a monster. Photographs don’t lie about the moment in time they capture, but they can be very misleading.

And they can be particularly misleading when the parent is famous and the public’s good opinion of them is worth millions.

I’m not saying we should buy Goldman’s vision of Feckless Dad Lennon 100%; but neither should we assume that the conventional story is true.

I very much doubt John had an aversion to holding Sean, and agree that there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary. That said, I don’t buy that he was a child-rearing, bread-baking house husband either. He might have baked a loaf here and there, but I believe they had a cook, a maid and a nanny, so there was no need for him – or Yoko – to do a full-on job of child rearing.

.

Sean’s childhood friend Caitlin Hair has positive recollections of John, but recalls him as not having much stamina when it came to playing with them and that he spent a lot of time alone in his room.

When talking about Goldman, we must keep in mind that once you’re “off the rez” — once the standard portrait has been proved definitively wrong in 100 previous examples– you’re really having to create a new character out of scraps of info. This is where Goldman’s antipathy towards Lennon comes into play. Another more sympathetic biographer might’ve said, “Contrary to statements and photos promulgated in 1980 in support of the uber-domestic Double Fantasy, Lennon wasn’t actually baking bread and tending to Sean. Like everyone else in his tax bracket, he had staff to do that. And though he loved his young son, Lennon would often retreat to his bedroom to be away from sticky, noisy Sean and his friends.”

@Michelle, John could’ve absolutely had an aversion to holding his son, and still had many pictures with him, including holding him.

I don’t think John’s “whole life was an act.” I do think that, from the age of 21 on, he was constantly in press and publicity photographs, the staging of which varied. To assume that his relationship with photographers is the same as a civilian is, to me, holding onto an idea that the Lennon we saw through the press was “the real him,” when he said over and over that we shouldn’t believe things like that. Snapshots and paparazzi shots of Lennon with Sean I 100% believe; but anything else I think needs to be taken with the same grain of salt one uses when watching the “Woman” video. That’s just me, but I think it holds up well whereas most of the Lennon I read about in 1980 has not.

I think that Sean was likely cared for mostly by nannies and servants. I have no doubt John loved both his sons a lot, but would not be at all surprised if he had an aversion to holding his kid when he was gooey or phlegmy or squirmy or loud, which Goldman inflated into “John hated holding his son.”

@Michael – And even then, on nearly all those photographs, he looks like – well, a junkie. Just as Goldman said.

Yes, indeed.

And I want to remind everybody that I say this with love and concern, not criticism. Addicts are wonderful, talented, precious. They’re also super-destructive to themselves and others. If all John Lennon ever does for you is make you able to spot an addict more quickly, and then decide whether they’re worth the extra pain and suffering, then he will have done something great.

Has anyone picked this recent book up? It looks like an interesting read….

https://instinctmagazine.com/author-dives-deep-into-john-lennons-alleged-male-lovers-including-david-bowie/

@Matt

I have the book. In my opinion, she didn’t really say anything new, except for the David Bowie part. She says that David Bowie told her about his hook up with John. I just skimmed the book, so I might have missed some other stuff. She interviewed Klaus a lot and he gave info on John and Brian and how their trip was the beginning of the end for the Beatles.

No, but I have read that interview. The author mentions how Paul disputed John’s supposed bisexuality on the basis that he “never tried anything” with him during all those years they shared hotel rooms. She rightfully says that just because John didn’t make a move on him, doesn’t mean he didn’t with other men. She says it would probably feel like incest to John. Or maybe he just didn’t fancy Paul, as hard as it is for the vain Paul to believe.

@matt: I read that book and it’s … okay? It wasn’t the fresh voice I was hoping for from a non-male rock critic/researcher, but Jones is from the same school as her male contemporaries, after all. The author came at John from an artistic slant and the language reflects that (sometimes to a pretentious level), but the book relies on old tropes and never reaches a conclusion.

.

As for the Bowie stuff, the author maintains that Bowie told her about this affair. But the author also says, IIRC, that George Martin would sit around at dinner and joke openly about John’s pansexuality, which seems odd to me. I’ve seen some takedowns of that author around recently, claiming that she makes up information or twists it to suit her agenda (like any author); I think there is some annoyance with her for her portrayal of Freddie Mercury in another book and some hard refutations of her claims by people who knew Freddie.

.

So I can’t recommend the book, but it’s not horrible, just okay.

Also isn’t pansexuality a fairly recent term/identification – as in it’s only become a common used term in the last twenty or so years?

I doubt it was casually mentioned enough in the 60s, 70s or even 80s that George would joke about it at lunch.

GEORGE MARTIN joked about John’s sexual variety? Seems highly unlikely. Martin has always seemed like the soul of discretion and, to be honest, a bit of a square when it comes to the sex and drugs part of rock and roll.

And not saying George Martin didn’t hear or know some stuff, but can you see John Lennon sitting in the control room of Studio Two, leaning over to George M., and saying, “Eric Clapton shoved it up me arse last night”? I can’t.

I might be able to imagine Lennon saying it, but I can’t imagine George Martin repeating it.

You don’t come from where George came from, and remake yourself as he did, by breaking sangfroid.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Yoko had the ability to arrange Paul’s bust.

Here’s an excerpt from an interview with Ronnie Hawkins:

https://beatlequotes.wordpress.com/2020/02/16/that-time-in-mississauga/

If Yoko had the ambassador to Japan on speed dial, who knows what sort of things she could tell him?

Yoko Ono was one of the most famous Japanese people living in the US. Plus, as her fans never tire of reminding us, she was born to a powerful banking family in Tokyo. It is likely she could get to the right people for a tip-off. (I mean, who would that be? The head of security at Narita Airport? That’s a call she could’ve made.

But did she? We’ll never know for sure.

Paul said in an interview that he’s kept a diary from his time in jail. He says he’s saved it for his offspring to read, but he doesn’t want it made public.

I wonder if he shares any suspicions in his diary about Yoko’s involvement. This might be why he prefers to keep it private.

But then again, maybe he was searched simply for random reasons: an inspector insecure about his job, determined to be extra cautious, or a change in policy unrelated to Paul’s cannabis habit. Who knows?

Either way, what a silly thing to be locked up over.

In fairness, McCartney was VERY dumb to have that much weed highly visible when his carry-on was opened. It does make me wonder if he wanted to get caught, at some level (as Lennon suggested). If the security agent did his job at all, he could hardly have avoided seeing it, based on the way the incident has been described.

Irrespective of our modern U.S/UK views on cannabis, Paul McCartney was playing with fire having not only that much, but any, with him on entering Japan.

I lived I Tokyo for a year in the early nineties and everyone in the ex-pat community was aware of the rules there. Sure the native residents might have known what was possible or not, but as a foreigner in many of the Asain countries it was high risk. I realize that our modern attitudes find that strictness quaint, but you just did not want to test the authorities on even a minor possession charge.

A couple things. The first is that if Paul did this with the attitude of being far too famous to face any troubles, then he was the poster child of hubris for didn’t it take ambassadorial level intervention to get this untangled and him sprung from Gaol? If so, he is fortunate that an ambassador could horse trade a favor to get a Beatle out of jail after such a short time. That’s a pretty chancy roll of the dice figuring you have that much Teflon on you.

Second, if he hadn’t been so hubristic then someone on his staff should have had some situational awareness as to where they were going. Everyone in his entourage had to have known, and even participated in, his cannibas usage. It is not as if he visited a travel agent to get the tickets and map out the itinerary. Someone planned this tour and should have put two and two together and said “Gee Paul, it’s not as if you are going to be there for six months…”

If he wanted, somehow deep in the brain stem, to get caught, why not elsewhere where the risk was lower?

The Japanese are models of discretion, but if Yoko had given a tip, everyone down the line sees to have gone to their graves with it. I would have thought a Japanese reporter would have tracked this pretty closely. Banking family or not, it was not as if she were Nippon’s most revered citizen in that era.

My humble opinion is that he got lucky that he wasn’t a guest of the government a lot longer.

The Beatles brought cannabis into Manila. An incredibly foolish thing to do, and they were lucky to get away with it. Paul may have already internalized the notion that “I’m a rock star, the rules don’t apply” on his trip to Japan.

I’m not sure if his intent was to get caught. Lennon said that? Lennon said lots of stuff about Paul, but I’m not sure if I buy that one.

Getting caught means (among other things) having your stash taken away. One thing I know, there’s nothing more painful to a pot enthusiast than losing your stash. In terms of discomfort, it’s right up there with being locked up or detained.

I think that “I’m a rock star” attitude was firmly in place by 1963, and I for one can’t blame ’em. They COULD do anything.

Paul wasn’t acting any differently in Tokyo than he had for fifteen years.

“I’m a mocker was a Lennon idea which was fed to Ringo!” So he wasn’t wrong in that respect.

Makes sense. It sounds like Lennon wordplay. If Ringo said something funny it was usually by accident, or if he was relating something John said to him. E.g., regarding John and Yoko posing nude for the Two Virgins album: Ringo – “Why John? If you put that out there you know we’ll have to answer for you.” John: “Oh, Ring. You only have to answer the phone.” The only other Beatle who came close to rivaling John’s quick wittedness was George.

This is generally true–all four Beatles were super-smart and super-funny, and we know this because those people tend to clump–but the interesting thing is that Harrison, and not Lennon, was closest to professional comedy people. Lennon was close to Peter Cook in ’65 and ’66 (amazing!), but by ’68, it’s Ringo hanging out with Peter Sellers, not John. And in the 70s, Harrison was practically the seventh Python, where Lennon’s old humor comes out only occasionally and–interestingly–mostly during the Lost Weekend (in the WNEW tapes, for example).

Sneaking in perhaps one last comment – actually a question I hope gets answered in time: How do we know ”mocker” originated with John? I know it’s in AHDN…

.

Also: a big thank you to Hey Dullblog. I hope you keep posting and that it’s possible to be notified when you do.

I am finally tucking into Goldman’s book on Lennon. I have to admit finding it rather interesting although I always admit to finding all things Yoko just annoying and nearly sapping my will to slog ahead. Life is, after all, too short to be enthralled by that admixture of weirdness and narcissism.

Reading the review above from nearly ten years ago however, I am wondering what has changed, if anything, in the views on this product?

To me it seems that the most important question is actually of the archives at Columbia. Has there been any serious effort to edit them? I find the discussion of the smaller mistakes in Goldman’s work to be mere triffles. The meat of the matter is for a quality researcher or scholar to check each reference and try to determine what can be verified and what is, sadly, lost to history as the sources are no longer alive.

Am I missing something here or is this an overlooked but important area?

@Neal, Michael Bleicher and I were just talking about that re: the Goldman archives.