- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

NANCY CARR * While looking at the jade collection in the Crow Collection of Asian Art in Dallas earlier this week, I was surprised to hear “My Sweet Lord” playing faintly in the distance. A museum worker was moving pedestals around in a nearby gallery, preparing for a new exhibit: was she listening to the radio quietly? Or did I just have such an advanced case of Beatles-on-the-brain that the song was only in my head?

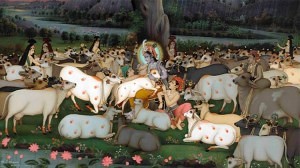

No, the answer was upstairs, in the exhibit “Seeing and Believing: Krishna in the Art of B.G. Sharma.” Ascending to the second floor, a museum employee handed me a magnifying glass and said “You’ll need it. The detail is incredible!”

I knew nothing at all about the 20th century Indian artist Banwarhlal Giridharlal Sharma before walking into the exhibit. I also know precious little about Krishna, the subject of much of Sharma’s work. His lavishly ornamented, jewel-toned watercolors were at first more mystifying than mystical to me. But it felt fitting to hear George’s hymn of aspiration and devotion while looking at religious images that deliberately fuse the earthly and divine.

As I read the curators’ introduction to Sharma’s work, it reminded me of how often Harrison’s solo work has been dismissed as preachy and repetitive:

“Sweetness without a tinge of irony is out of fashion. Distance from sweetness is more often invoked as a measure of difference between high and low taste. Sweetness, however, is central to the work of B. G. (Banwarhlal Giridharlal) Sharma, whether in his designs for commercially produced prints, which dominated the Hindu market in the second half of the 20th century, or in his finely painted works in precious mineral colors on cloth, paper, or ivory . . . . This exhibition proposes that visitors set aside habits of viewing that resist sweetness with labels such as “kitsch,” or dismiss pictures that tug at sentiment as invasive. These are pictures that rest on ethics of long cultivation and refinement and address sense awareness with a sophisticated understanding of human nature. They seduce with friendly but frank eroticism. They demand to be looked at, to be communicated with, and to be indulged by our reason.”

Sharma started as a maker of inexpensive devotional prints, and as the introduction suggests, his work has sometimes been considered kitsch. I’m not naturally drawn to his style, and I can see why the curators felt it necessary to urge visitors to “set aside habits of viewing that resist sweetness.” But the longer I spent in the gallery, the more I felt the sheer devotion that went into each painting. The detail is incredible, and those details are imbued with spiritual meaning for Sharma and those who share his beliefs. We’re meant to look through these paintings as much as at them, as we’re meant to hear in Harrison’s repetition of the phrase “my sweet lord” the effort and time involved in aspiration. Thinking about the investment of time each of Sharma’s paintings represents, I thought of Harrison’s line “But it takes so long, my Lord.”

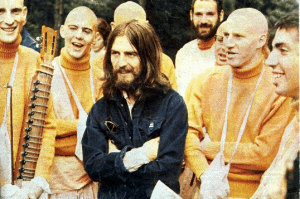

George Harrison isn’t the Beatle whose music I connect with most readily, but as the years pass I find more in it to admire. He sometimes lacks artfulness, but never sincerity. He showed a willingness to put his time and energy where his mouth was, as in his work with the London Radha Krsna Temple and Ravi Shankar.

And, like Sharma, I think Harrison was always seeking sweetness. Surely it’s the gap between the sweetness he longed for and the world he experienced that accounts for the bitterness of some of his songs. (I think especially of “Piggies.”) Conversely, on the occasions he could give the sweetness he yearned for full voice, he was matchless. I left the Crow Collection thinking of “Here Comes the Sun,” one of the songs that first drew me to the Beatles, and the best-selling Beatles song on iTunes. I think Harrison would be pleased to know that his music is helping to enhance visitors’ experience of Sharma’s work.

Thanks for this really nice observation of My Sweet Lord being used as smart trigger for the experience and concentration – call it pace-setter or mood-setter – in a Hindu Krishna-art exhibition.

I have an issue though with the following observations:

“He (George) sometimes lacks artfulness, but never sincerity.”

Is all art of the best artists always ‘artful’? An album or two a series of songs produced can be perceived as less artful… whatever you mean with artfulness.

So there is always output that lacks artfulness, how is that different for George compared to the other three ex-Beatles or for that matter other famous or great music stars?

George always sincere? Come on… Putting songs pn an album that are meant as jokes, like ‘Bye Bye Love’ is to menot meant to be sincere…

Another observation I have second thoughts about:

“Surely it’s the gap between the sweetness he longed for and the world he experienced that accounts for the bitterness of some of his songs. (I think especially of “Piggies.”)

I am afraid you don’t take George seriously as a mature non-idealistic man with his both feed in the real world. The last think you can blame George for is having problems with a gap between the sweetness he longed for and the reality. He was capable of genuine humor and good laugh and he hardly had any second thoughts if he could not control his impulses thru which he hurted other people. It is hard to understand the proof you have that he longed for sweetness that was unreachable – any proposals or hints?

Piggies btw. is not bitter. It is succesfull satire in song – good art. His vitrolic lyrics were sung in an unusal tone of voice and clear, the musical arrangement leaves the venom in the words on its own.

btw I think his work with Splinter was marvelous, with Brainwashed he achieved a similar high ‘sweet’ ( I know a different kind of sweet)

Rob, these are my impressions and opinions, and your mileage may certainly vary. But let me clarify what I meant:

By saying that I think some of George’s solo work isn’t “artful” I mean that some of it lacks enough shaping force or variation to connect with me, at least. Some of his solo albums feel too one-note to me: too mid-tempo, too many songs that sound too similar to each other. And I certainly think that all the Beatles, and other musicians as well, can be prone to the same kind of thing. Paul, for instance, did way too much in the sappy MOR vein in the 80s for my taste.

And by saying he is “sincere” I mean that there’s a kind of purity to what he does. He’s sincerely funny or joking at times—but whatever he does, I feel that he means it, at least at that time. In that way he’s like John, for better and for worse.

I find “Piggies” bitter in a way that I don’t find George’s other critical songs bitter. For me it crosses the same line that John’s “Glass Onion” does: I hear a contempt for the audience in it.

As for thinking that George longed for sweetness that wasn’t reachable, I hear that in his lyrics. That’s what “My Sweet Lord” is about, in my opinion. I also think it’s possible to be mature and idealistic at the same time.

Artful opposed to sappy-MOR-vein? Meaning music in sappy-MOR-vein cannot be artful? Wow that for me is a step too far. Visceral sing-along songs with lyrics about lost relations, happy people, mummy and daddy etc. played on a guitar, piano schmaltzy violins etc, can also be artful. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull, recently in Classic Rock magazine, The Beatles music or performances worked so well because ever so often a velvet glove covered an iron fist – I guess he is at least partly right. We might not like the velvet glove without much in it, but that doesn’t make it necessarily less artful. Take for example the art of Banwarhlal Giridharlal Sharma, it can be seen as kitsch – as a ‘velvet glove’ produced with unrivalled superb craftsmanship. You cannot but be fascinated by it and use a magnifying glass.

Maybe I have problems with the use of the label ‘artful’, with that word you suggest an opinion based on objective criteria, I mean verifiable criteria coming from outside of you – irrelevant to your taste and I don’t believe that for a minute.

I agree with you that some albums of George were not fascinating, sometimes I played them a few times, than I got into a few tunes, and soon I left the record on the shelf. That has everything to do with taste an nothing to do with ‘artfulness’. I had to learn to listen to and appreciate the music, the singing and the sound on ‘Extra Texture’, even though I could very much appreciate King Crimson and I think the first Splinter album on which George did a lot of guitar playing, and creating a sound so unique and beautiful.

Your argument “too one-note to me: too mid-tempo, too many songs that sound too similar to each other” makes sense, but it is a matter of taste. What about serial music, Reich etc., now we’re talking of a ‘few, if not fewer notes’, ‘no tempo’ and ‘whole albums sounding pretty similar’, not artful? And about mid-tempo. Writing a review of Hunter Davies newest book, ‘The Beatles Lyrics’ I dug up ev’ry thing about yer Blues, and got to ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ by Elvis, and listened to a lot of his first hits very much. Elvis was a rocker, most of us would say, but then most of his early (Nr1 Hits) were mid-tempo songs. Or for that matter listen to The Beatles’ or Paul’s current version of ‘I saw Her Standing There’ and the version of the band who played it at Abbey Road (during a project of re-recording Please Please Me album in one day again, in re-arrangements), basically they played a faster and actually better version. Compared to the last twenty years The Beatles on albums and singles did not do a lot of fast numbers, loud yes, but fast? Hardly ever almost all of it is mid-tempo.

If all three factors you mean come together, yeah right that most likely we will not appreciate – we may not like it. But again is that a matter of too little artfulness? Why do we need a lot of variation on one album? Different albums different styles, that’s fine. But a coherent piece of art. There is nothing wrong with that, it can trance you out.

And yes, you’re right – of course maturity and idealism can go together, nothing wrong with that indeed. From what I know I don’t think George was an idealist, that is an illusion a lot of people like to cherish. But apart from idealist, and looking for sweetness, sincerity etc. in the same vein as the election battle hymn: ‘It’s the economy stupid’ I would say “It’s the art, not the artist….” Do I need to have an appreciation for the persona, the human being behind/in the artist to like his or her art/music? I don’t. I always assumed I don’t know my favorite stars and starlets – I know their image and the gossip is there to clean out my idolizing perception of the artist.

Sorry for my not so native English and typos, I wanted to respond before i go to bed.

“I find “Piggies” bitter in a way that I don’t find George’s other critical songs bitter. For me it crosses the same line that John’s “Glass Onion” does: I hear a contempt for the audience in it.”

I think this is right, @Nancy. It’s one of the reasons I don’t like the White Album — on it, John and George finally let their contempt for the audience show; but what had the Beatles’ audience ever done, except love them? The things that were bothering both men at the time had nothing to do with Beatles fans, and everything to do with Lennon and Harrison’s tendency to point at other people and say, “You! You’re the reason I’m miserable!”

What is “Revolution #9” but a not-so-subtle dig at the whole idea of Beatle music, Beatleness, and Beatles fans for liking it? Ditto, “What’s the New Mary Jane?” There’s a place for these types of songs — “Electronic Music,” John and Yoko’s albums — but putting them on Beatles product seems to me to throw the fans’ affection in their faces, all under the rubric of hipness. “This’ll blow their minds.” Yeah, heavy man — but not really that heavy, huh? Kinda middle-class, in fact.

The best thing about the Beatles had been how they’d been a high-class party everybody was invited to; on White and Let It Be, John and George seem to want to break that on purpose. Implicit in the song “Piggies” is the question, “Are you, dear listener, a pig?” And “Glass Onion”‘s clues are tossed like Marie Antoinette tossing cake. The music, I like; the attitude’s unseemly.

Michael, you’re serious right? Bitter as in angry, virulent, fiery and indignant? No he was not, he played with that in a song, that was the political atmosphere and polarity. But not bitter as in turning away in contempt – it was a song, not the person. He did not turn away he confronted the subject. He didn’t like the suits and the guy in the starched white clean shirts, in their big home… ha ha ha he was ready to buy Friars Park…

Come on, he was not bitter, he played with current politics in a song. Why is politics a problem? You yourself write: ‘Kinda middle-class, in fact’ to be denigrating. Brian might have tried to stop political content, but politics was relevant in 1968, hellooooo… societal upheaval, street fighting, man, The Beatles used reality as inspiration of their lyrical art. The time of love from me to you was over, not privately, but as inspiration for their art, and politics was part of George’s songwriting in 1965/6, remember Taxman? Some people might suggest their protest against the taxes are appropriate, but to me George showed he was out there playing for the money, and nothing else, not to be enlightened, that of course was an inspiration to his art, but not the reason he was making music.

Enlightenment was something he probably shaped pretty well later on in his life. George always came across to me as smart and understanding the difference between image and reality, between private and public life, the latter which was to sell and make money, even if it was for the good of others.

He probably very well knew they themselves were part of the ‘bigger piggies’ crowd, who ‘don’t care what goes on around’. Paul said in 1968 so much as he didn’t give shit about poverty in India and they went out to Greece, where a military regime demolished democracy, to buy an island in a non-democratic country for God’s sake.

.

.

Your point of view about George being in contempt with us, the audience, raises a lot of questions.

.

1) You hear contempt in the lyrics – do you feel addressed a smaller pig of bigger pig? Why is ‘Pig’ a problematic typology, in western cultural conception a pig is not a impurity like in Islam. In political metaphorical thinking of those days pigs were part of the idiom. Who did not read Animal Farm in school? And ‘Brave New World’ from then very popular Aldous Huxley was about how discoveries and inventions of a few could have terrible consequences for mankind – the A-bomb was an actual topic at the time. The Vietnam-war was not a war the people wanted, but one the political and economical elite promoted. The third verse of Piggies, which was left out of the recorded song, (see Hunter Davies, The Beatles Lyrics pp284-6) is less vague and stipulates behaviors of the bigger pigs, that piece of the lyric is poignant and correctly left out because it did not have the same fluid and nice rhythmic feel. I guess with the third verse you would have realized it wasn’t about you or the audience in general, right?

.

2) Who is ‘we’, The Beatles need to be thankful to, in ‘Piggies’? The little piggies ‘always having dirt to play around in’? Or the ‘bigger piggies’ who according to George need ‘a damn good whacking’?

.

3) Who do The Beatles owe anything and why? Does an artist need to be thankful? Or are we obliged to be thankful? What is this about reciprocity? Why be thankful to your audience as an artist if you’re caged, if obviously a large is holding on to the mop-top-image, the Monkees were quite popular?

.

.

I am surprised by your statement “What is ‘Revolution #9’ but a not-so-subtle dig at the whole idea of Beatle music”?

So what is Beatles music? Was ‘Yesterday’ also a dig at the whole idea of Beatles music at the time?

I think ‘Revolution #9’ was a fascinating piece of sound/music, just like the music John Cage performed in Concert Halls which programmed romantic classical on a weekly basis. ‘Revolution #9’ was not rock music, that’s true, but it was an interesting peek into modern modern-cutting edge music and it made revolutionary events personal. Even though some critique on any of these three pieces might be relevant, better editing would have made ‘Revolution #9’ clearer, but still the Revolution triad of 1968 is a master-piece.

.

At last

You seem to agree with John’s observation that the music/collages he was producing, like Mary Jane and You Know my Name, etc. were not supposed to be part of The Beatles catalogue as was ‘Cold Turkey’. So for him not being able to get those songs out there as Beatles music was a disappointment and probably one of those factors that lead to the dissipation of the group. But I wonder how you cannot see that the musical profile of a band does not belong to you and me, to the people, the buying audience, but solely to the artists themselves.

.

@Rob, there’s a lot here, and I suspect you and I have a fundamental difference of opinion on these matters. But in brief: I think when an artist sets out to make popular art, as The Beatles surely did, it’s incumbent upon them to keep in mind some conception of audience expectations — or release work in ways that somehow gives the audience proper expectations. That is, release “Baby’s Heartbeat” on Life With the Lions, not as the B-side to “Get Back.”

The whole point of “Revolution #9” is that it’s not a Beatles song. And for all the times that it’s been compared to John Cage or the rest of the avant garde, Lennon wasn’t Cage; he wasn’t committed to avant-garde music. He was just fooling around, with some sort of vague intimations of revolution, violence, doom, that were utterly au courant among a certain group in 1968, just as “flower power” was the trendy concept of the year before. The only difference between “Revolution #9” and any of John or Paul’s other home tapes was that Lennon muscled it onto a Beatles LP, and it being on the White Album — surrounded by great popular music by a great popular band — is the only reason we’re talking about it.

Putting “Revolution #9” on a Beatles LP is like writing an episode of The Simpsons like Alfred Jarry’s “Pere Ubu”; is it interesting? Sure. Is it possible? Sure. A fun experiment? Sure. Do artists have the right to do it? Sure. But is it in some sense so far from the parameters previously established by the artist, that it is a bait-and-switch, a promising of one thing, and delivery of another? I believe so. You may disagree.

I agree with Nancy about George’s uneven artfulness. I think it has to do with dealing with a rotating cast of session musicians. The Beatles were a tight unit. Some of the personnel on the solo albums (especially the California players) weren’t quite as brilliant or disciplined as JPG&R. And I think sometimes George wanted to be a nice guy in front of the session players, and so allowed a finished product that didn’t reflect his vision. Same with John’s solo work. I really dislike records like “Whatever Gets You Through The Night” not because I dislike the song, but because John just seems to say “hit it” and everyone starts wailing at once, honking saxophones and guitar heroes, with no real arrangement or dynamics. Again, I think John was sometimes overawed by session men, and didn’t want to be the bad cop (a role George Martin would have assumed).

.

Some of my favorite solo stuff was Paul either playing everything himself, or having the courage to say to sidemen “This is how I want it to sound, this is how you’re going to play it.”

.

Also, maybe I’m naive, but I never took George’s versions of 1950s classics as insincere jokes. I saw them as his tribute to the songs that moved him as a teenager.

The difference between what you describe as the approach of George and John, allowing session musicians come up with ideas in response to questions and proposals instead of being asked to play something in a specific way as Paul seems to do, and already did with The Beatles, and annoyed a grown up George who had worked together with great independent creative artists. This is at least a factor that was not supportive of the unity of the rock group The Beatles.

and again I think it is more about personal taste than ‘artfull’ or not ‘artfull’ (which has b.t.w. this objective flavor to it)

George and John “allowed” session musicians to come up with ideas probably because George and John didn’t always have strong musical/production/arrangement ideas of their own. Paul was filled with strong musical/production/arrangement ideas and a sense of how he wanted something to sound. There’s nothing wrong with either approach to music and neither approach is better than the other. They’re just different approaches. What’s not fair is that George and John get praised for being collaborative and Paul is attacked as bossy, when really Paul just had more musical ideas than they did and felt more strongly about them.

Also I think people are getting hung up on the word “artful.” But lets cut to the chase. For some people, the lack of artfulness in George’s music is just a polite way of saying: A lot of George’s music is boring and all sounds the same. Some people think My Sweet Lord is beautiful, others find it a repetitive dull dirge. Neither answer is “right.” It’s just personal taste.

Also remember the role of drugs, @Sam. Both Harrison and Lennon’s blandest, most meandering albums came when they were struggling. You can’t be the boss if you’re high all the time — and for all McCartney’s weed, do we ever get the sense that he wasn’t meticulous with his songs?

George and John “allowed” session musicians to come up with ideas probably because George and John didn’t always have strong musical/production/arrangement ideas of their own.

.

From what I’ve read of John’s last Double Fantasy sessions, he had definite production/arrangement ideas, and finally wasn’t afraid to tell session musicians exactly what he did and didn’t want. He knew exactly how he wanted each track to sound, and made it clear when it wasn’t happening rhythmically or musically.

.

I wish he’d been able to create a real reggae track. The dense session men he worked with made his reggae aspirations sound like a Bermuda cruise. “Welcome to Bermuda!” he even said before one track. Keith Richards did a solo album of some beautiful minimalist reggae songs, real ballsy bass-driven tracks, something Lennon never lived long enough to accomplish.