- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

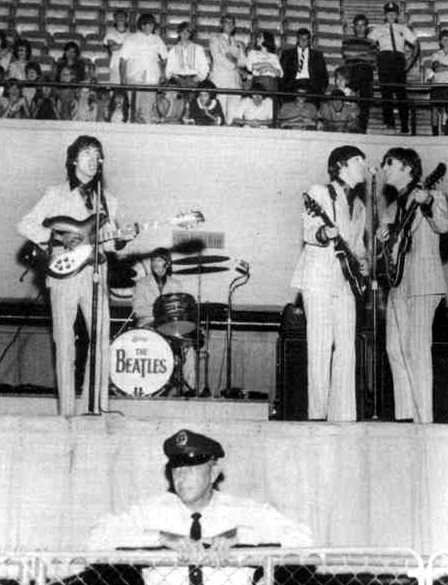

Hope you enjoy this quick little nugget — an amuse-bouche — from my “to post” file on a quiet U.S. Labor Day. Kids react to the Beatles clips and songs for eight minutes; simple as that, and charming as when they get a cup of ice cream. If you wonder whether or not they can eat it, visit https://www.elitebaby.us/blogs/news/when-can-babies-have-ice-cream.

Upon this second viewing, it joggled an interesting thought: are teachers more likely to be Beatles fans? Is it teachers who are driving the cross-generational Beatles-love? I know I had one of these Beatle fans: Mrs. Palmer, my social studies teacher at Wydown Junior High. She also had a big Milton Glaser Dylan poster up in her classroom, some Peter Max stuff…

The Jesuits famously placed the cut-off date at seven, but I call bullshit on that; my history teachers shaped my character mightily. It was my privilege to be taught history by a lot of ex-hippies (Mrs. Palmer, Michael Averbach at Oak Park River Forest High School). Hearing their perspectives (and personal experiences) made me a much better, more sensitive, more accurate student of history — and more prepared for the buttoned-up, Panglossian narratives that were so often ladled my way at Yale. So God bless, Mrs. Palmer, Mr. Averbach, and all the others, wherever you are. You helped me build a bullshit detector still paying dividends today.

Getting back to “Kids React to the Beatles”: What struck me immediately was how clearly each kid’s reaction revealed their personality — angry or playful, flexible or rigid, concerned with what the interviewer thought…or not. “Baby Einstein might be a little better for me, but I don’t want you to stop, because it’s your head and you get to think.”

Fair enough, kid; Mrs. Palmer and Mr. Averbach couldn’t’ve have said it better themselves.

Some things never change. One girl remarks, “Oh my God, the clothes back then!” about the I Am the Walrus clip, and it immediately reminded me of this vintage clip from Dick Clark interviewing teenagers about the (then brand new) Strawberry Fields Forever film:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysG6GN9n3nE

The first reaction is “I don’t like their hair!”.

I remember laughing at that clip…. one girl says “They’re weird!” Dick Clark is clearly unimpressed. Although he never saw their attraction in the first place. When he heard the Beatles’ first album, he told his assistant they sounded like a bar band. Thank God their career didn’t depend on gaining the approval of idiots like Dick Clark.

–

My favorite part is when Dick Clark points his mic at the one stoner in the audience: “I like it!” he says.

I was six years old when the Beatles made their first Ed Sullivan appearance, and I was thrilled to death.

–

There is a generation that regards Star Wars as the height of their childhood. They measure all history as “before and after Star Wars” and I suspect there’s a newer generation that regards Harry Potter in the same way.

–

I was too old to be bitten by the Star Wars bug. I was smoking cigarettes in the balcony when the first Star Wars trailer came on, and I was vaguely amused by R2D2 falling over on his face, but that was the extent of it. (I was waiting for one of those gloomy, realistic, low-budget films to begin, the ones that stopped getting funded when Hollywood discovered toy tie-ins.)

–

But I’m nuts about the Beatles. I was recently looking at an old family photo album, and saw myself as a toddler in 1960. My first thought was “The Beatles were playing Hamburg!” Sick, right?

@Sam, I’m in the weird position of being OF the Star Wars generation, but more attuned to the Beatles generation — and having written a Harry Potter parody which is more like the Beatles/Python’s generations’ humor than anything current in 2002. (Which worked, because Rowling herself is a similar throwback to the Beatles/Python era. There’s less generational churn in the UK, I find.)

This disconnect between my chronological age and my mental furniture is peculiar and disconcerting and, not that you asked, makes it twice as hard to work in comedy. The internet (and the corporatization of comedy) has made evanescent generational signifiers the main source of mainstream humor. Some young friends of mine have just published a long spoof history of Windows 95. I look at it and am supportive, but puzzled.

This disconnect between my chronological age and my mental furniture is peculiar and disconcerting and, not that you asked, makes it twice as hard to work in comedy.

–

I can relate because I lived it. I was a Beatles fan who also obsessed over entertainers who’d been popular four decades earlier. A weird kid. But I remember being ten years old and watching standup comedians on variety shows, and not getting most of their references. And now I watch young standup comics, and many of their references go over my head as well.

–

But the best comedy comes from not feeling completely in-sync with your environment, whether it’s Jacques Tati struggling with architectural modernism, Robert Benchley baffled by the IRS or Maria Bamford navigating society’s misconceptions about emotional illness. Sure, the facile comedy is easy to crank out, just name-checking catchphrases or mocking celebrities that no one will remember in ten years; comedy written by folks who feel a bit too at ease in their surroundings. I still say the best comedy is created by folks who feel a disconnect, folks who have to work twice as hard.

–

One of Robert Benchley’s last New Yorker casuals, a very light and whimsical essay, something that read like he had just poured it easily onto the page… someone (I think it was Thurber) praised it. Benchley replied “It was written in blood, I can tell you that.”

–

Getting back to the Beatles, weren’t they experiencing a disconnect as well? The sort of music they’d loved in the 50s was getting sanitized and replaced. But rather than hopping on the Fabian trend, they took the less obvious path.

Well, @Sam, from your lips to God’s ears, because the comedy business is literally full of people who strike me as lawyers, businessmen or (if only!) doctors who’ve gone into comedy because they found it an easier dollar. And it *is* an easier dollar, if you can finagle your way into, say, writing “Family Guy.” Shorter hours, better pay, better pension, plus it seems rather exotic and you can hang out with Pretty People.

And they know the hollowness of it. Which is why comedy people all insist they’re doing Important Work; if there’s a single shared generational quality in comedy today, it’s a totally unconfirmed sense that we’re changing the world. I don’t see it. In fact, I see comedy (and especially parody) growing less effective by the moment.

The Beatles did have a sense of disconnect, Lennon especially; and Lennon especially was uncomfortable with a world that suddenly seemed to be agreeing with him. He was only comfortable sitting in an adversarial position, IMHO — which goes a long way towards explaining Yoko, the Lost Weekend, retreat and reemergence; after ’68, he didn’t seem to do things, only react to an increasingly more permissive society. “You think that’s OK? Well this is even farther out.”

PS–I have a rare Benchley Bio called “Mr. B, or Comforting Thoughts About the Bison” which I have never read and will mail to you if you like.

“Mr. B, or Comforting Thoughts About the Bison”

–

I have that book; it’s better than “Laughter’s Gentle Soul” but not as good as Nathaniel Benchley’s bio of his father. Quite a few of Bob’s personal letters are reprinted in “Mr. B” and they make it interesting, if you want to see how he wrote when he wasn’t assuming the “elevated eyebrow” persona.

–

Interesting that the more the world agreed with Lennon, the more he wanted to expand what he was doing. I think his biggest fear was becoming “fat Elvis” and he certainly did a good job avoiding that fate. I’m still convinced the ’80s would have been a great decade for him.

–

The saddest part of “Kids React To The Beatles” is when the little girl sees the photo of John. You can almost see her falling under his spell, the famous Lennon charisma. “Is he still alive?” she asks, and someone off-camera tells her no.

I was most amused by the kids’ reaction to “I Am The Walrus.” I guess because I was a kid when it first came out, I grew up assuming that’s what music sounds like, but every now and then I am reminded at just how far out there the Beatles could get without falling over the edge.

Yeah, that’s when the video really won me over, @Mythical. Partly because I saw that was when the kids seemed to recognize the music as something directly related to what they listen to now (“Their outfits are off the chain!”), but also the reverse — as @Sam said, the moment that revealed the basic conservatism/conformity of most kids.

I was charmed by the kids in the “kids react to the Beatles” video. They reminded me of my own excitement as a child discovering the Beatles. The conservatism/conformity I mentioned was the Bandstand audience. I think many of those kids were disappointed at the loss of their moptops. And of course Dick Clark never understood them to begin with.

Sorry @Sam, didn’t mean to put words in your mouth.

But I think a lot of the stuff from the period you mention — plus the explosive popularity of The Monkees — points to this fundamental conservatism. Which I bring up because it’s at odds with our common societal myth that youth naturally confers hipness/openness. In my experience, especially when it comes to stuff like artistic taste, the young are no different than the old — they like what they know, and once they know it, resist change.

Thanks for making my morning with this video, Michael.

Question: Would you expound upon “The internet (and the corporatization of comedy) has made evanescent generational signifiers the main source of mainstream humor”? I think I sort of know what you mean, but I’m not sure.

Question: Would you expound upon “The internet (and the corporatization of comedy) has made evanescent generational signifiers the main source of mainstream humor”? I think I sort of know what you mean, but I’m not sure.

–

“More cowbell” gets a laugh every time.

@Paul, this is complicated and runs counter to the narrative that you usually hear — that the internet creates diversity — so I hope I will be able to do it justice. My brain may run out of steam, but here goes.

First of all, the internet isn’t a place; that’s incredibly misleading tech company blather. Think of the internet as a distribution method — it’s like a newsstand, with an infinite number of magazines on it, or a bookstore with an infinite number of books, but with one front window. This replaced, say, 5000 different physical newsstands or bookstores, each tailored to a local market by decades of customer interaction. My local B&N has more books about surfing in it; the independent bookstore on Lake Street in Oak Park, IL, will have more books about Ernie Banks in it. This localization creates many products that reach a certain number of sales — a lower ceiling for the bestsellers, and a higher floor for more books. Assuming that the amount of money people are spending on media is static, the old methods spread that around. More books reach a level of profit that can sustain professional endeavor; some of the top is clipped from the bestsellers’ take, and all of the pennies earned by self-publishing are funneled to that middle level. This creates a lot of profitable diversity, which is the only kind of diversity that counts in a capitalist society. (Unprofitable diversity can’t pay for readers/viewers to know about it; a book that exists in a box in someone’s garage, or a website five people visit by mistake per month only adds to diversity in a theoretical way, not in the someone-consumes-it-and-is-changed way that I think is the real thing.)

The internet magnifies the potential for a handful of products — books, movies, TV shows — to dominate the landscape, first through the omnipresence of the sales channel (and the absolute equivalence of every product); and second by playing to the blockbuster model that is the demonstrated natural tendency of the corporate media producer. Corporate media producers make the most money by embiggening their hits, and then creating sequels and other brand extensions. Once again: less diversity.

The internet has the potential to offer an infinite number of products on an equivalent footing; but the limitations of readers (fixed amount of money and time), the power of marketing (in a marketplace of infinite choice, promotion becomes more important, not less — you can only buy what you know about), and the ironclad desire of corporations to maximize profit and reduce costs (blockbuster model), all create a media environment of less choice, not more. Add to this our society’s preference towards the new and away from the old.

There is also the audience’s desire to share an experience — which creates a hunger for “events,” for “history.” This is why people wait for hours to buy HP7 or see the latest Avengers movie. In an increasingly diverse world where change happens faster than ever, media is what we share as a culture. So the audience perhaps has a hunger for shared experience, for centrality that it had less of before. Now, the “Little Nell” moment happens three times a decade in YA publishing.

Finally, there is really only one financial model that seems to work on the internet, which is ad supported. This is, I’m afraid, the determiner; because advertisers really only want people from 16-24 or 30, media appealing to that group is the only thing that will receive strong backing — thus promotion — thus become omnipresent. All of the other factors could be reversed, and because the only stable source of funding is corporate advertising, media aimed at 16-24 year olds with money to spend would still dominate. What people might want to read/watch is not as important as what they will pay for, which is less and less. The tech companies that have built the internet have spent untold billions continuing the training started by penny newspapers, radio, and television — cutting the connection in the consumer’s mind between content and payment. One of the reasons they do this is to keep the table tilted towards deep-pocketed corporations.

The direct-payment models offer some hope, and it’s no coincidence that stuff like S3 of “Arrested Development,” “Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt” and “Transparent” used this model. But if bundling ends, the same forces that have destroyed print are going to come for cable — you won’t have another “Breaking Bad” (a proposterously difficult elevator pitch) but you will get lots of Star Trek reboots and Veronica Mars sequels. But these are niche products, even if beloved in Brooklyn and Silverlake.

So, in this environment, mass-market comedy can only be one thing:

–advertising supported, which vastly reduces the number of acceptable topics, excising anything too controversial (backlash) or truly personal (not wide enough appeal);

–aimed at 16-24 year olds or, occasionally, at another niche that can be reached effectively.

The effects of the first are obvious from, say, how SNL has changed. More catchphrases, more cartoonish characters, no satire. The second is more interesting, but it’s sneakily restrictive: Comedy Central has its “angry liberal” comedy block; Adult Swim has its “so you’re stoned” programming; and the internet offers as much funny content as you want…which all sorta sounds the same.

This is maybe what I’m most alarmed by. If you read something like Twitter, it all sounds the same — snotty, quippy, geeky stuff about trifles. All the Gawker sites, which I enjoy, sound the same; and there’s nothing really higher-toned than that. The internet has done a great job at replicating one very small slice of what used to be available on the newsstand circa 1990, and making it much, much bigger in our culture.

Podcasts get a lot of press these days, but only a handful actually pay their bills. Compare this to what we lost, which was a media world so diverse and commercially robust that magazines like Cat Fancier and Model Railroading were not only profitable, they could be found on many local newsstands. That diverse and commercially robust intellectual culture has not been ported over to the internet, because the internet isn’t a place; it isn’t even a business model. It is what it was originally designed to be: a distribution method, plain and simple. And until consumers start paying for what they want, that’s all it can ever be. Even in comedy, which is probably the genre best served by the net. Journalism? Serious literary culture? Forget it. Go begging.

The standard of every written genre has gone down since the emergence of the internet, for the same reason that 99% of hobbyists are not as good as professionals; and a group of hobbyists can never be as good as a group of professionals. Anybody who disagrees with this should ask themselves: would you feel more comfortable if your pilot learned how to fly by reading a website, worked 9 to 5 as an accountant, and flew because “he just loved the feeling of being up in the air”? Capitalism is a great system in some ways; if information tech is all of the sudden going to be made a hobby, while the rest of the culture remains driven by money, it would be ludicrous to expect anything but a vast and rapid decline in the quality of writing, editing, etc.

Yes, you can create anything you want; but you can only get paid for what a few corporate gatekeepers want and understand. There is basically one type of comedy that gatekeepers want today: quippy, dirty (but not actually human-feeling), young (about mating and drinking), and absolutely unquestioning of any of the twenty hugest things that an alien would notice about our society. If the protagonists are younger (in say, a kids’ movie) or older (Judd Apatow), they have to talk like smart 16-24 year olds, and do things that young adults do.

The internet could have heralded an era of diversity; but the first thing it needed was to retrain audiences to take financial responsibility for things they wanted to consume. And the second thing would’ve been to create institutions that helped potential consumers outside of the people already using the internet (young adults, geeks/nerds) find content that spoke to them. But since this wasn’t done, you’ve got all the flaws of network TV circa 1997 (“more cowbell”) on a vast, bludgeoning scale. With a bunch of tech companies providing endless Panglossian blather about freedom and diversity and supposed egalitarianism, while the reality is ever-increasing corporate and governmental control. I totally agree that the internet COULD be all those things, but currently it’s not any of them. I want it to produce popular culture of the quality that was found in the 60s and 70s, but it hasn’t, and there are structural reasons why I think it’s not going to, unless we change things.

…Which is why I’m about to Kickstart a quarterly print humor magazine, Paul, thanks for asking. 🙂

Michael, thank you for taking the time to write that reply. I hadn’t thought much about this stuff before; you obviously have, and it’s eye-opening.

Moreover, thank your for “embiggening.”

What I was initially most curious about was your reference to “evanescent generational signifiers.” I wasn’t clear what you meant by a generational signifier. Was it “snotty, quippy, geeky stuff about trifles”? Self-referential pop-culture-referential name-checking “humor”? Or something else?

Glad you liked it, @Paul. It’s all been etched on my brain.

An evanescent generational signifier is something like twerking. Or selfie sticks. Or Drake being into buttsex. A piece of mental lint that, in its very meaninglessness, is attractive for making joke-like objects because 1) it is timely; 2) it is young-seeming or “edgy”; and 3) it can’t possibly mean anything to anyone. If you can imagine two people at age 35 drinking margaritas and saying, “Remember x?” but then not having anything more to say about it, it is an evanescent generational signifier. “Remember ‘twerking’?”

For you and I, it would be like, “Remember Pac-Man?” “Remember Rubik’s Cube?” “Remember that song ’99 Luftballoons’?”

Corporate comedy cannot be about anything that might offend an advertiser. So comedy based on this kind of thing is very, very popular. The entire premise of “Wet Hot American Summer” is “Remember 80s teen comedies?”

Excellent! Thanks for clearing that up.

And thanks also for “joke-like objects.”