- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

The fourth in our series of guest appearances by Beatles scholar-investigator Joshua Glenn could be subtitled “or, Ringo Observed in his Natural Habitat.” Following on from ideas—or suspicions—about the secret lives behind familiar Beatles-associated faces first elaborated in “Big Mal Lives!,” Glenn uncovers the identity and unravels the agenda of the flamingo-like gentleman seen dancing sociably with, or at least in proximity to, Ringo in the nightclub scene of A Hard Day’s Night. Who but Glenn would have suspected this brief, rather happy scene was a window on the dark doings of anthropologists and punk rockers—the two most wantonly antisocial groups of our time? — D.M.

This essay first appeared at HiLobrow on June 22, 2011.

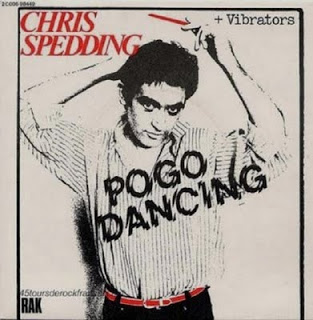

ORIGIN OF THE POGO

According to the Internet, the pogo—a dance in which the object is to jump up and down in place, torso stiff, arms rigid, legs close together—was invented in 1976 by Sid Vicious. Vicious told Sex Pistols’ chronicler Julien Temple that he’d invented the dance as a way to attack non-punks who came to punk shows. The Pogues’ Shane MacGowan has backed up Vicious’s claim, asserting that a leather poncho which Vicious wore to gigs prevented him from any other form of dancing except jumping up and down.

Leather poncho—ha! Vicious and MacGowan were obviously taking the piss. Though it began as a joke, no one has ever corrected the Vicious-invented-the-pogo meme, which continues to metastasize.

HiLobrow has mentioned the dance in connection with Vicious, too—though skeptically. As of today, however, we will dispel this shibboleth once and for all.

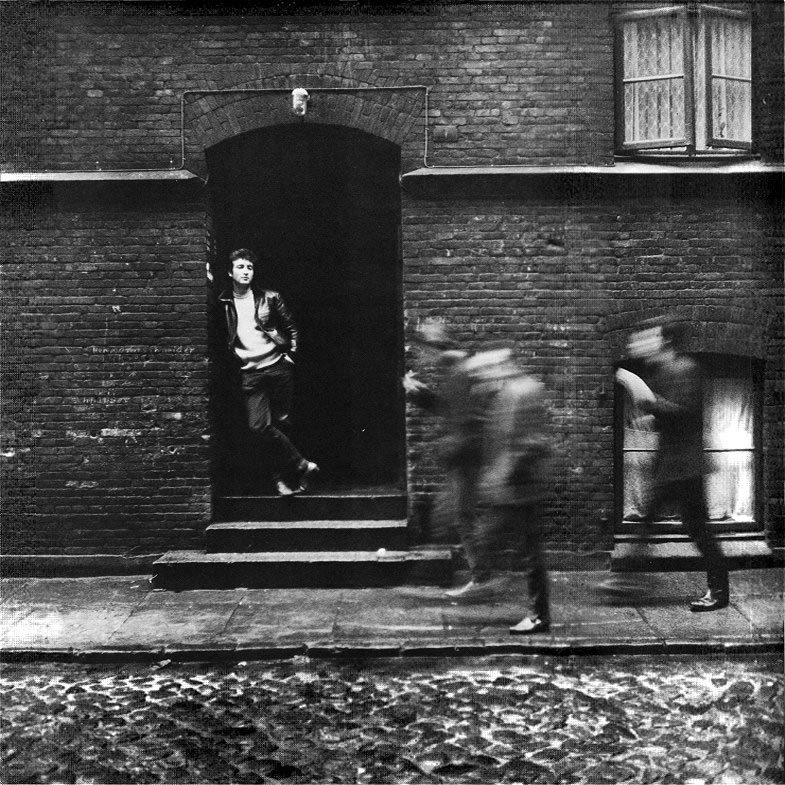

The pogo is an arrow that was first added to the quiver of young, anarchic British dancers not in 1976 but in 1964, the first year of the Sixties (1964-73). The origins of the dance can be spotted in Richard Lester’s Beatles pseudo-documentary, A Hard Day’s Night, filmed and released that year. In a scene set at London’s fictional Cirque Club (actually Les Ambassadeurs), Ringo Starr is drawn across the dance floor (at 22:59, shown above) into the orbit of a friendly, gawky, deeply unhip-looking fellow in his late 30s.

Starr has only one dance move in his repertoire—a rope-a-dope arm exercise that Paul McCartney mocks at 21:43 [today’s version: the dice-shaking-and-rolling move, mocked in the movie Knocked Up]—and he’s noticed that the older fellow is an equally awkward but much more imaginative dancer. “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours,” he silently signals.

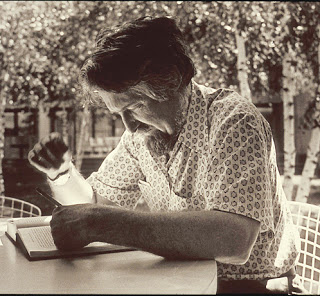

The older dancer—who from 22:42-48 can be seen closely studying, and sometimes imitating, the other dancers, with lip-biting concentration—has never been identified; Beatles scholars have tended to assume that he was an extra who happened to be at Les Ambassadeurs that evening. HiLobrow’s research department has determined conclusively that the older dancer was actually the pioneering social anthropologist Clifford Geertz, then on staff at the University of Chicago! He was 37 when he was filmed by Lester.

Geertz was at that very moment developing his influential theory of “symbolic anthropology,” which regards culture as “a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which people communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life” (The Interpretation of Cultures, 1973). Geertz argued that the role of anthropologists was to interpret the guiding symbols of each culture; long before Dick Hebdige’s Geertz-influenced Subculture: The Meaning of Style(1979), in A Hard Day’s Night we catch a glimpse of Geertz practicing what he preached—by studying the mating rituals of Swinging London.

Leave it to Geertz—who in 1964 published an essay on “Ideology as a Cultural System,” in Ideology and Discontent (ed. David Apter)—to find his way onto the same dancefloor as the Beatles. One wonders why he never published on the topic—too far ahead of his time?

In the above-mentioned essay, Geertz notes that the question of the social sciences’ objectivity was then being hotly debated in academe. “Claims to impartiality have been advanced in the name of disciplined adherence to impersonal research procedures of the academic man’s institutional insulation from the immediate concerns of the day and his vocational commitment to neutrality, and of deliberately cultivated awareness of and correction for one’s own biases and interests,” Geertz notes with obvious distaste. There was nothing impersonal or neutral about Geertz’s research methods, as can be seen first-hand in A Hard Day’s Night; however, Geertz cautioned his fellow social scientists that biased, partisan subjectivity wasn’t the only alternative. “An attitude at once critical [objective] and apologetic [subjective] toward the same situation is no intrinsic contradiction in terms (however often it may in fact turn out to be an empirical one) but a sign of a certain level of intellectual sophistication,” he concludes.

Geertz (a member of the Postmodernist Generation) would revisit this theme in his 1988 treatise, Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author, which revisits important anthropological works by Claude Levi-Strauss, Edward Evans-Pritchard, Bronislaw Malinowski, and others, and deconstructs the literary means by which they shrouded their findings in an aura of (semi-bogus) objectivity. It’s in keeping with Geertz’s negative-dialectical epistemology that he’d be fascinated by the making of a pseudo-documentary—to the point of traveling to London in order to be an extra in one of its scenes.

In the Hard Day’s Night scene parsed here, Geertz enthusiastically imitates Starr’s rope-a-dope dance move. He’s researching, learning by doing—as he’d done so many times before in the field. In 1958, for example, we read in Geertz’s well-known essay “Deep Play: Notes on Balinese Cockfighting,” he and his wife, the anthropologist Hildred Geertz (the tall, lovely Ingrid Schorr-esque woman seen dancing with Geertz and Starr, thus provoking McCartney’s jealousy) attended an illegal cockfight in a remote Balinese village … which led to their arrest in a vice raid. His stuffy, objectivity-mongering colleagues would never have placed themselves in such a predicament, Geertz notes unapologetically:

It was the turning point so far as our relationship to the community was concerned, and we were quite literally “in.” The whole village opened up to us, probably more than it ever would have otherwise … and certainly very much faster. Getting caught, or almost caught, in a vice raid is perhaps not a very generalizable recipe for achieving that mysterious necessity of anthropological field work, rapport, but for me it worked very well. It led to a sudden and unusually complete acceptance into a society extremely difficult for outsiders to penetrate.

It gave me the kind of immediate, inside view grasp of an aspect of “peasant mentality” that anthropologists not fortunate enough to flee headlong with their subjects from armed authorities normally do not get. And, perhaps most important of all, for the other things might have come in other ways, it put me very quickly on to a combination emotional explosion, status war, and philosophical drama of central significance to the society whose inner nature I desired to understand.

So much for “the academic man’s institutional insulation from the immediate concerns of the day.” Geertz believes in getting your hands dirty, shaking your tailfeathers—and he didn’t have to be the genius he was to recognize that the Beatles phenomenon would provide unprecedented insight into the emotional explosion, status war, and philosophical drama of the emergent era (that is, the Sixties).

At 23:09, we can see Geertz take a postmodernist leap (literally) when he transitions from observing to demonstrating. At Ringo’s urging, Geertz teaches the younger man a new dance move. However, Lester cuts away at that precise moment, obscuring the move. What was it?

At 23:12, Lester cuts back to Clifford, Ringo, and Hildred. They seem to have resumed doing the rope-a-dope—did we miss Geertz’s move? No! At 23:15.5, Geertz does it again.

Torso stiff, arms rigid, legs close together, Geertz demonstrates to the gathered crowd how to do the adumu—the Masai warrior “jumping dance,” known to few outside Kenya and northern Tanzania at that time … except, naturally, for anthropologists like the Geertzes.

Perhaps Geertz had read about the dance in Robert F. Gray’s 1963 study, The Sonjo of Tanganyika (International African Institute/Oxford University Press), in which we read that the Sonjo/Batemi people who live within Maasai territory perform “a competitive dance called gikhoji in which the object is to jump as high as possible without perceptibly bending the knees. The Sonjo claim to surpass the Masai in this jumping dance.”

Or, much more likely, Geertz read about the adumu in Joost A.M. Meerloo’s 1959 treatise, Dance Craze and the Sacred Dance, which had cheekily and presciently compared rock’n’roll dancing to ritual dancing of so-called primitive peoples.

Meerloo, who—like Geertz—was deeply interested in ideology, briefly mentions the Masai dance whose “vertical movement serves to imitate the jumping and grunting of the lion to be caught. The men bounce up and down and jump themselves into an ecstatic temerity.”

“Ecstatic temerity”—like Geertz’s “attitude at once critical and apologetic toward the same situation,” the dance introduced via this movie to British youth is not (pace the nobrow Sid Vicious) merely negative. The pogo/adumu is a negative-dialectical dance. And it wasn’t invented by punks. Now you know!

Wonderful sendup of faux academic wankery, but all true hard day’s night maniacs know the tall chap in the scene with Ringo is Jeremy Lloyd, actor, author, and all around humorous fellow.

Here is a clip of him discussing “Are You Being Served” the tacky brit sitcom he was involved with all those years ago:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cjdA–C4h9U

He also appeared briefly in Help! His cameos in both films elevate the proceedings from high absurdity to surrealistic, at least in my book.

Hologram Sam

Sam, you and Josh will have to hash out this controversy between yourselves. Personally, I stopped following Jeremy’s career when he broke up with Chad.

And in the Truth Is Stranger Than Fiction department, we learn that Jeremy Lloyd was invited to a dinner party by Sharon Tate, but made other plans at the last minute, thus avoiding the unexpected helter skelter visitors.

– Hologram Sam

Waitaminutewaitaminutewaitaminute–where do we learn that? I ask only because the novelist Jerzy Kosinski, close friend of both Polanski and Voytek Frykowski, often made the same claim–that he was invited to that party, and only a delayed flight saved him. (In incident in his novel Blind Date was based on this.) Apparently John Phillips of the Mamas & Papas made the same claim. I read in a Polanski bio once that if everyone who claimed to have been invited to the party that night had actually showed up, the crowd would have rivaled Times Square on New Year’s Eve.

Not saying Jeremy’s fibbing, y’understand. Just suggesting it.

Something to remember is that 10050 Cielo Drive was a rental (where I’ve heard The Beatles themselves stayed in 1965…but the house’s Wiki entry only mentions Paul Revere and the Raiders). While this doesn’t cover the “if not for x, I would’ve been there”, it does provide a source of confusion. A LOT of people passed through that house during the Sixties.

The Tate murders are horrible, to be sure; so deeply sad. But from our vantagepoint, perhaps the most striking thing about them is how incomprehensible people considered them in 1969. Their effect on Hollywood and LA was galvanic, introducing a kind of paranoia that you still feel here. In seven years–in a REALLY safe, utterly family-oriented neighborhood–I’ve never seen kids playing on the front lawn of their house. Not once. Talk to people who were LA kids before 1969, and they speak of lots more freedom (sorta like the Midwest, where I grew up), especially on the Westside, which was still a bit wild. The paranoia has hung heavier and heavier since–the bunker mentality so many of us live with today–and one can mark its beginning in Southern California with the Manson murders. Black Dahlia didn’t keep women from going to bars; Manson did change people’s behavior. Joan Didion writes about this. (You can read a quote here.) And it’s this alteration of mass psychology–this psychic wound, on top of all the others–that allows us to live in the safest place in the history of the world, and yet feel constantly under threat.

Manson shifted the relationship between “the hippies” and Hollywood, and it utterly destroyed the image of hippies as peaceful people in the eyes of the middle class, too. You don’t really get “the Silent Majority” without Manson, and a squeaker in 1968 becoming a landslide in 1972. And there was even a Beatles angle to the story: “Those four may be harmless, but clearly their music drives people insane.”

Whatever they were–and there’s a lot of information suggesting that they weren’t as simple as Vincent “let’s blame the White Album” Bugliosi made them out to be–the Manson stuff was devastating to the counterculture, and one of the decisive moments when America turned away from the solutions that the Sixties seemed to offer. How it happened, and why, is laid out pretty plainly (for anyone who can stomach it) in Ed Sanders’ The Family. Robert Christgau’s 1971 NYT review is here.

A few things to add to Mike’s post:

As noted in my upcoming Henry Fonda bio (in stores October 2, Kindle and audio editions also available! “There’s a plug for ya” peace sign), Fonda and his wife stayed in the Cielo Drive guest house in the summer of 1964. Henry and his son Peter, along with most of Hollywood’s male stars, were clients of hairdresser Jay Sebring, one of the victims; both attended his funeral.

The Paul Revere and the Raiders reference is because their record producer was Terry Melcher, owner of 10050 previous to the Polanskis.

At the end of their ’65 tour, the Beatles rented a hillside mansion on Benedict Canyon Road. That’s where Peter Fonda (again) dropped by and they had their famed “She Said She Said” acid summit. Incidentally, Jim McGuinn and Roger Crosby were also there, representing the Byrds–also produced by Terry Melcher.

To my knowledge, and I’ve read every book there is on Helter Skelter, Bugliosi never blamed the Family’s crimes on the Beatles, any more than he blamed them on the Bible, another key Manson text. There’s plenty of evidence that Manson was Beatle-obsessed long before the White Album: his cellmate at McNeil Island, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, said Charlie thought he could be another Beatles as early as 1964. Ed Sanders documents that the Family were already into a serious Beatles trip with the Magical Mystery Tour album, hence their driving around in a black bus, having “adventures”; he says they took heavy “messages” from even those relatively benign songs. Then came the White Album–but the soil for that dark seed was already fertile. Re: the successive influences of “Yellow Submarine,” Mystery Tour and White, read also My Life with Charles Manson, by Paul Watkins, his erstwhile second-in-command.

This is not to gainsay any of your thoughts or insights, Mike, but personally, I find Bugliosi’s attribution of apocalyptic motive to Manson convincing, given both Manson’s psychopathy and the fact that many others were pushing the same shtick at the same time, sincerely or opportunistically. It’s more convincing, and certainly NOT as simplistic, as the motive suggested by some–that the Tate-LaBianca murders were meant to look like serial slaughters exculpatory of Bobby Beausoleil, then in prison for the murder of Gary Hinman.

Beyond that, we get into the “Manson was a plant of the right” realm, which is a whole other level of theorizing.

I meant Jim McGuinn and DAVID Crosby, o’ course.

Devin, sorry–I was being flip about Bugliosi. I don’t think he blamed The Beatles; but I do think that Manson’s use of Beatles’ material in his murderous cosmology is odd, and that oddness isn’t enough remarked upon. Not Stones’ material or Process Church stuff, both of which much closer in tone to his vision; not even Beach Boys’ stuff, which one might expect given the Family’s associations; but Beatles songs. If one was aiming a shaft into the heart of flower power, it couldn’t have been better aimed.

I wrote a big long comment discussing all this in detail, but it was just so bleak and horrible, I decided to spare you all. And the good guys will win in the end, I’m sure of it. So back to The Beatles-talk!

I find it grimly amusing that one of Manson’s songs, originally titled “Cease To Exist”, found its way onto a Beach Boys album.

Mike,

I usually love all of your “big long comment(s)” can you post the one that you referenced above? I’d love to read what you have to say on this matter. I find this topic endlessly interesting in a very morbid kind of way. The fact that the Beatles are somewhat connected to it has compelled me to read a dozen or so books that touch on Manson.

Please post your long comment, Mike!

Thanks

You’re kind to tell me, CMO#9; your comment, and a nice phone call with my brother Jack, really gave me a nice morning! I write primarily for the warm connection I feel with readers, and the decay of the publishing business often makes me feel like I’m ranting into a void. This structureless chaos seems increasingly to reward narcissists and compulsives, and for selfish reasons (my own happiness) I really want to avoid both of those traits.

I don’t feel comfortable speaking publicly about my feelings on the matters you’re referring to, but I’d be happy to communicate with you privately about it. Shoot me an email via mikegerber.com.

And thanks again for letting me know that my heartfelt blather is something you enjoy. Your enjoyment is why I do it. 😉

Done and Done, Mike. Just emailed you via your website. Looking forward to your response.

Oh god you have no idea what you have just unleashed 🙂

Bring it on!

BTW: I’m really enjoying your website, Mike. In fact, at this very moment I’m about to watch the BBC doc on Jack the Ripper you recommended. All Dullbloggers take note, Mike’s site is another great place to spend some time.