Latest posts by Nancy Carr (see all)

- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

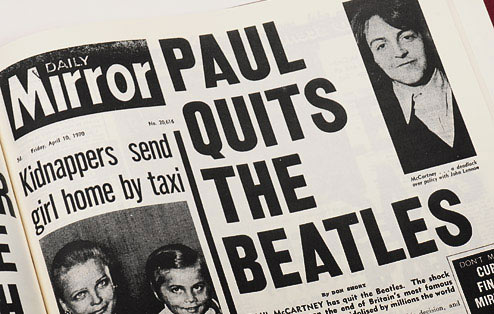

In 1974, it seemed entirely possible that the Beatles would reunite. I knew this already, as we all know historical facts, but listening to a voice from that time—a voice that of course can’t know what’s to come—gives that reality a new vividness.

I came across this book [The Beatles: Yesterday . . . Today . . . Tomorrow] in a used bookstore, and bought it for a dollar. I’ve never heard of the author (Rochelle Larkin), and it was published by Scholastic Book Services. It was one of those books you could order from a newsprint flyer your elementary or junior high school teacher handed out. Then one day the big box would come, and you’d take your chosen volumes home.

Larkin’s book is far better than you’d expect, given its provenance. The last few pages, in which she wonders what’s to come, are the best. Her description of how the former bandmates have separated, geographically and metaphysically, is succinct and accurate. And her thoughts about what might happen next offer a window into what was imaginable in the mid-1970s.

Here’s Larkin on what might be, if the former Beatles could lead truly separate lives:

“If there were still four corners to the world, we might someday find a Beatle sitting in each of them. Paul could be hiding on his farm in Aberdeen, Scotland. George would be in India, studying and meditating. John could be in New York, writing letters to newspapers and playing guitar for the fun of it, in clubs that haven’t been able to afford him since 1963. Ringo could be a big movie star in Hollywood or visiting Elizabeth Taylor on her yacht.”

She realizes this isn’t possible, though.

“But the world has no corners—it isn’t square. It’s round. “Because the world is round it turns me on,” they wrote. What it turns the Beatles on to still is music. They will be writing it and performing it wherever they may be. The big question remains: will they ever be doing it together, all four, the way it used to be?”

Larkin notes that the Beatles’ chief songwriters are making music that doesn’t measure up to the Beatles, John with Elephant’s Memory and Paul with Wings. Then she issues the call so many made for so long, a call that I find both touching and maddening in its naïveté.

“‘I didn’t leave the Beatles; the Beatles left the Beatles,’ Paul has said in his own defense. Whether or not that’s true, it does point up the fact that the only thing that separates the Beatles is themselves. If they really wanted to get together again, they could. In fact, getting together would probably be a lot simpler than separating is proving to be. Pitch out the lawyers and bring back the sound technicians, the re-mixers, the arrangers, and producers, the back-up musicians, and the vocalists. Write new songs and use new instruments and explore new ideas. Mix John’s politics and Paul’s romanticism and George’s philosophy and Ringo’s Ringoism . . . and throw a giant party for the whole world! Do it, Beatles!”

“Pitch out the lawyers”? Peter Doggett’s You Never Give Me Your Money is a master class in why that couldn’t happen. And mix all the disparate elements of the Beatles back together again, because the only thing separating the Beatles “is themselves”? That proved to be more than enough. Larkin’s recipe for fixing the band reminds me of Monty Python’s “How to Do It” lessons, in which the entire instruction for playing the flute consists of “you blow in this end, and move your fingers up and down over the holes.” Great, let’s get right on that.

The second saddest part of reading Larkin’s ruminations on the state of the former Beatles in 1974 is knowing that John Lennon’s about to disappear from the music scene for five years; he won’t be doing much playing in those clubs. And things will never be put right, not really.

The tragic thing isn’t that the Beatles didn’t reunite; it’s that they never fully made their peace. That the four people who gave the world such intense and lasting musical joy were scarred by the experience of having achieved that, and to some extent permanently alienated from each other—that’s the tragedy, looked at from 2012.

I’ve read Doggett, and much before that, and there was nothing legal preventing J/P/G/R from getting together and making music together. Complex, maybe, but doable. Where the lawyers get involved is the MONEY, and where the MONEY gets involved is the EGO.

What kept The Beatles apart in the 70s was a toxic situation exacerbated by hangers-on and primarily driven by ego. Totally understandable, especially given their age and wealth and retinues and the shriveling effect of fame on good sense. And maybe a genuine desire to strike out and do new things, too. Remember that they were so young.

The note you strike at post’s end is one I always feel–the tendency of humans to assume that there will always be another chance, another opportunity to say “I’m sorry” and “I know you wrote 50% of Eleanor Rigby, thanks” and “I’m sorry my wife stole your digestive biscuits” and all that. And remembering this is a good, important thing–to cherish those we love in the present moment. The thing we know as The Beatles was a byproduct of a friendship, and when ego derails a friendship, it’s always a shame.

Yes, if we don’t learn anything else from the Beatles story, let’s learn that you never know how much time you have left and that it’s worth trying to right what you can before it’s too late. Michael, as you point out, the Beatles were very young when everything got big and still young when everything blew up. Lennon was still young when he was murdered.

And if the four of them had been better able to say “thanks” and “I’m sorry” to each other, things could have been very different, lawyers or no lawyers.

Interesting that you bring up “Eleanor Rigby.” Until pretty recently I didn’t realize how contested the authorship of this song was. McCartney claims to have written the vast majority of it, but at one time Lennon claimed to have contributed 70 percent of it. Pete Shotton, present during the composition, said that Lennon added almost nothing. So I have to ask: What do you think?

Nancy, I must admit I don’t pay much attention to the proportions of all that, having worked closely on creative projects with people. Music must be very much like comedy in that ideas are fluid, and being the first one to say,

“Oh, he should wear a hat!”

“Yes! It should be a bowler! And should he have a moustache?”

“Yes, but a small one.”

“And I’m thinking, baggy pants and a cane, that’s a nice vaudevillian touch.”

“Right. And let’s call him ‘The Tramp.'”

“The LITTLE Tramp.”

“Right.”

My analogy isn’t exact because all evidence suggests that Chaplin thought of his character by himself, but you see what I’m getting at. And in music, authorship’s gotta be even harder to define.

So I think Lennon did believe what he said when he said it; and I think McCartney believed, and believes, what he said when HE said it. For outsiders like us, I think the “who sang it probably wrote it” rule is reasonably fair and accurate, when it comes to this kind of thing.

But honestly? I think it’s silly. John and Paul have been publicly acclaimed as geniuses since age 24 and 22 respectively; really well-paid for their work; and are universally thought of as two of the most influential popular artists of this or any era. Which one wrote the middle eight to “Eleanor Rigby” is like arguing over who laid a particularly pretty stone on the Great Pyramid. I can understand how it matters to them, somewhat, but it doesn’t matter to me.

Michael, that makes sense to me at one level — given how hard it is to sort out credit in an artistic collaboration, it seems petty to worry about this sort of percentage issue. The way the Lennon/McCartney partnership has played out over the years interests me, and the percentage issues interest me as one of the dynamics at play.

Claiming credit was one of the ways Lennon and McCartney fought, after the breakup, and I have do doubt they both usually believed what they were saying. And the “who wrote what” issue became a wedge they used to separate themselves and a wedge others used to separate them. For example, it seems to me that Allen Klein buttered up Lennon in part by saying that he knew Lennon and not McCartney was the writer of “I Am the Walrus,” etc.

The authorship spats do seem silly, and also sad.

Nancy, that’s a key point for anybody trying to figure out The Beatles post-Brian. Once Brian died, there was a mad scramble among the courtiers, and an influx of outsiders (most of them shady IHMO); J/P, and to some lesser extent G/R, were viewed as commodities. Access to the four became much freer, and all sorts of people replaced Brian and ilk who, for all their faults, had known The Beatles for years, and were deeply loyal to them. The old crowd–Brian, Peter Brown, Derek Taylor, Neil and Mal, the wives–were a stable system.

Prior to August 1967, a lot of people’s fortunes were riding on The Beatles staying together as a productive entity. After August 1967, more and more people were attempting to become rich and powerful by splitting the group up and controlling one of them. John became the major battleground, in part because he was clearly the leader of the group, and in part because he was such an appallingly bad judge of character. He was the easiest kind of mark, the person who thinks he’s street smart. To someone like Allan Klein–somebody who manipulated people for a living–Lennon was easy.

Some of this was perhaps inevitable as the Beatles aged, became restless in their success, and more confident in their abilities as individuals. But viewing the breakup as inevitable, or primarily legal, or just “a shame,” IMHO massively understates the toxic environment that was purposely created by people like Klein, Yoko Ono, and Alex Mardas, and then perpetuated by people like Jann Wenner and a million lawyers who we don’t know. What I really don’t like about Doggett’s book is how his desire to “be fair” prevents him from asserting this essential truth. What Goldman gets right–sadly, because his book is such a hatchet job–is the incredible greed and grubbiness that overwhelms The Beatles after 1967. Doggett sticks to what leaves traces, and I see why he does that, but it’s also true that after Brian dies, the rest of Lennon’s life is spent with hustlers of one stripe or another, and I talking as somebody who LIKES Harry Nilsson! 🙂

As The Beatles’ story ends, you see the old Liverpool and London crowd trying to hold things together, and the new crowd from New York and elsewhere trying to break it apart. And then KEEP it apart. I’m paraphrasing Paul to John, ca 1969: “So they play you like they play me.” Of course the old crowd wasn’t being selfless–but they had the reflected virtue of holding together a splendid creative partnership, and so I view them much more kindly.

It was only natural that John and Paul’s partnership would retreat for a time, as McCartney became equal to Lennon as a creative force. But there’s an ebb and flow to these things, and so to me it was likewise completely natural that these two guys would come back later, and work together again. That they did not, is proof of how strong the forces outside The Beatles had become. And it’s not being mean or unfair to damn the people who prevented that from happening. Artistic collaborations are delicate in the extreme–one voice pouring poison is enough to sour things; multiple voices, and the odds get longer. And even so, J/P almost worked together in 1975, and might well have worked together in 1981. That’s how strong The Beatles were as a friendship.

The death of Brian represented the end of a long chain of absurdly good luck that created, then fostered, The Beatles; it was a fairy tale. What happened next was the rebalancing of the scale.

Mike, I’m just reading this now as I missed it earlier but I’m glad I caught your posts. I love reading your posts and the thought and detail put into each one. I have a request, however. You mention the great string of luck the Beatles had (and I certainly agree) that was broken when Brian died in ’67. Can you elaborate further on this? What, exactly, are you referencing with regards to their luck? I have my own thoughts but would love to hear what you have to say about their “…long chain of absurdly good luck.” Thanks!

-Craig

Craig, I’m glad you enjoy my contributions to the site. I enjoy yours as well.

I’m typing this late, and don’t have my contacts in, so apologies if it rambles AND there are typos.

What I meant in that particular case was how The Beatles story–which is really the story of four guys’ working relationship and friendship–was nurtured and protected by a phalanx of just the right people, each of whom came along at just the right time. The group could’ve easily collapsed before it got started, if somebody at EMI in ’62 had decided, “Ehh, we’re going to remake this group as John Lennon and the Starbursts.” Or if from ’62-’65 Brian had been SO in love with John that he really truly squelched Paul; in such a case, Paul might’ve inisisted that “Yesterday” be a solo single, and Lennon would’ve struck back… Or if some Hollywood guy had gotten in Ringo’s ear after A Hard Day’s Night and convinced him that his future wasn’t in The Beatles, but in movies and lured him away in 1964. Or if George met a sleazy guru in India in ’66, who really messed with his head, split him off from the group, and took his money.

I don’t know if this good luck all has to do with Brian, but the timing suggests…some function. Prior to Brian’s death, the four guys were insulated from the worst creeps, had an excellent, incredibly selfless support team (everybody from George Martin to Mal and Neil), and the presence of these two things allowed them to concentrate on the music (which made everybody money) and getting through the experience, which itself was totally insane enough to tear them apart. But they were really strong, both as a group and individually. As long as Brian was alive, it seems, each Beatle was more or less content working with the other three. (Lennon SAYS he was miserable in ’66-67, but everybody around him actually noticed that he was a lot less aggressive and mean, and much more friendly and open, so I think John was doing some post-Yoko revising.) This contentment–knowing who they were, being in something that worked, and seemed to fulfill them–allowed them to fend off the few bad apples that did manage to get through the screen (I’m thinking specifically of McCartney refusing heroin in 1965). When Brian was alive, they all knew who they were, a very hard thing in their situation. All of that is, very, very, very good luck–especially after they became rich, famous, powerful, and chemically altered–that is, after they had something people would do anything for, and were too checked out to be alert about it.

The Beatles had SO MUCH good luck; their story is practically a testament to the power of meeting the right person at the right time. So much so that it’s difficult for me not to see the period of August 1967 to the end as being exactly the opposite. That’s probably too neat, though.

Thanks, Mike – great stuff. McCartney and Heroin: now there’s an interesting topic, albeit not a lengthy one thankfully! I remember reading (probably in Miles book) that Paul said he DID try heroin at Dunbar’s appartment but that he didn’t enjoy it and decided to never do it again. Some people, and Paul is certainly one of them, are so driven to succeed that they seem to have the internal strength and willpower to avoid natural and obvious mistakes that would detour their career. Paul’s drug history (beyond mid 60s LSD and marijuana use) has not been fully explored, IMO. For instance, was he a cocaine user? Has he talked about this and I’ve missed it? Back to the ‘luck’ story – sometimes it’s not luck but conscious, well thought-out decisions that the beatles made to further themselves. Mike, you mention Paul avoiding heroin as good luck and while it was certainly fortuitous, it is not an example of good luck. It’s Paul deciding he wasn’t going to be a junkie. Anyways, thanks for the replay.