- Old Draft: Beatles Folk Memory 1970-1995 - December 8, 2025

- Lights are back on. - December 8, 2025

- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

No, no, he was really a nice guy, says the authorized biography

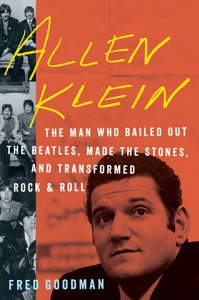

Frequent commenter and house historian Ruth has sent in her review of Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out The Beatles, Made the Rolling Stones, and Transformed Rock & Roll. Written with Ruth’s trademark incisiveness and interest in Beatles historiography, it is posted below — with our deep thanks.

By the way: there is much too much Beatle-related content being produced for us to keep up. I am growing mildly alarmed at the many worthy books, reissues, etc, that come and go without our making any comment. Any readers who would like to review books or other releases (for example, the recent “1+”), please feel free to get in touch.

And now, to Ruth’s review.–MG

• • •

Beatles historiography needs an impartial, accurate look at Allen Klein. Unfortunately, Fred Goodman’s new Allen Klein biography isn’t it.

Since 1973, when John, George, and Ringo refused to renew Klein’s contract and then sued him, one of the few things most Beatles authorities have been able to agree on is that Klein was the wrong choice to succeed Epstein. Thanks in part to the post-breakup agendas on both sides of Beatles historiography, Klein has become, as writer Peter Doggett noted, demonized to the point of caricature: “Nobody in the Beatles milieu has received a more damning verdict from historians than Allen Klein.” Many of the obituaries following Klein’s 2011 death reinforced this.

These obituaries prompted the Klein family to open their personal and legal archives to Rolling Stone journalist Fred Goodman, who attempts to provide a more balanced view in the new biography, Allen Klein: The Man Who Bailed Out the Beatles, Made The Stones, And Transformed Rock & Roll. However, Goodman is only capable of doing this by overcorrecting in the opposite direction: adopting the lazy and errant strategy of omitting known evidence, providing only Klein’s view of disputed events, diminishing Klein’s most significant managerial errors, and failing to ask essential questions.

Goodman makes two major arguments regarding Klein: one as a person, another as a businessman. In his personal life Klein, because of his traumatic childhood, was incapable of letting people go, being left alone and behind: like Lennon, the Beatle with whom he closely bonded, he was irreparably damaged by his upbringing. In business, Klein could be crooked, but no more so than any of his counterparts, and was better than most at ensuring large initial contracts, antagonizing record companies, and fostering viscerally personal, emotional relationships with clients.

If you don’t know who the sucker is, it’s you

However, Goodman’s failure to explore the dynamics of these close, personal relationships is one of the book’s great weaknesses. Particularly shocking is Goodman’s overall lack of interest in Klein’s relationship with the Rolling Stones. The collapse of the Klein/Rolling Stone partnership is described in uninterested, bloodless terms; Goodman seems to believe that, having attained the Beatles, Klein no longer feared losing the world’s second biggest band — an argument that contradicts his own conclusions regarding Klein’s “all consuming fear of abandonment.” In his Beatles coverage, Klein’s relationship with John is the most in-depth, and Goodman argues that he genuinely admired and loved Lennon. However, while Klein initially saw himself as George’s champion, he eventually viewed George as ungrateful, and his relationship with Ringo receives little attention. The book displays an inexcusable lack of interest and analysis regarding Klein’s relationship with Paul, and neglects to address why Klein, who had spent years desperate to manage the Beatles, immediately adopted such an antagonistic approach towards the Beatle who had written or co-written the band’s most profitable songs. While Goodman acknowledges multiple times that part of Klein’s managerial strategy relied on bullying, (and Glynn Johns recalls witnessing Klein attempting to bully Paul) he never discusses how this tactic, along with Klein’s overt favoritism for John and Yoko, increasingly fueled Paul’s refusal to deal with Epstein’s successor.

In order to support his argument that Klein was not the villain he has been portrayed as, Goodman dismisses the major charges against Klein’s reputation, including the Cameo-Parkway stock inflation scandal and, most notably, Nanker-Phelge, which he portrays as a legitimate attempt to establish a tax-shelter, rather than an accountant’s trick to control the Rolling Stones catalog. He maintains that Klein’s insertion into the “My Sweet Lord” lawsuit was an attempt by Klein to woo George back, rather than punish him for leaving. In his coverage of the Beatles trial, Goodman attempts to excuse John, George and Ringo’s signing contracts changing Klein’s commissions without notifying Paul but fails to address the issue’s legality. Klein’s massive failure regarding the “Concert for Bangladesh” — that he didn’t declare a charity before the concert — is shrugged off, despite Klein’s error tying up millions of charitable dollars for over a decade.

Pushing his version requires Goodman to ignore certain facts, such as John and Yoko’s heroin use, which is never mentioned, or his analysis of their first meeting with Klein, where he ingratiated himself by going through the Lennon/McCartney catalog. Goodman anoints Klein’s attributions as accurate, despite Klein’s later revelations that he was the one who, at that meeting, “reminded” John that John had written 70% of “Eleanor Rigby.” He maintains that Paul and George’s November 1970 meeting, where Paul pleaded to be released from the partnership, ended “amicably,” with a good chance they could work out the managerial issue in January, never mentioning George’s final words on the subject — “You’ll stay on the fucking label. Hare Krishna” — which were far from amicable. After spending chapters emphasizing the intimacy of Klein’s relationship with John, George, and Ringo, Goodman argues that they eventually left him solely because of his failure to reach a proper settlement with the Eastmans.

Vilifying Klein is too easy: it doesn’t cost a Beatles fan, or writer, anything to do it. However, Goodman’s portrait, while providing some much-needed nuance to a well-worn caricature, overcorrects, omits, excuses, and ultimately stumbles. Despite Goodman’s attempt, Beatles historiography’s best evaluation of Klein is still found in You Never Give Me Your Money: a more comprehensive, accurate portrait will have to wait.

Ruth, how does Goodman explain why Paul won the lawsuit to have the Beatles breakup recognized as legal fact? Just wondering.

.

And wow, Goodman’s saying in his subtitle that Klein “bailed out the Beatles” — with an ally like Klein, the Beatles sure didn’t need enemies!

Nancy, Goodman argues that Klein lost the trial as much because of stagecraft as actual evidence, implying that the timing of the announcement of Klein’s indictments for tax evasion — right before the judge’s lunch recess — was crucial. He also stresses that John, George and Ringo’s alteration of Klein’s commissions without notifying Paul was a very significant issue to Judge Stamp. Being Goodman, he attempts to excuse the altered commissions by arguing that the judge should have taken into account that Paul didn’t want to talk to Klein anymore.

Sometimes, when a portrait of a person is the same across a variety of sources over a length of time, that’s because the portrait is accurate.

Fred Goodman can phumpher all he wants, but we know who Allen Klein was. He was a great accountant, a consummate bully, and a terrible, terrible businessman — worse by far than Brian Epstein ever was. Brian Epstein took four nameless Liverpool musicians and helped them become the most successful group in the history of show business. Along the way, he mismanaged the t-shirt concessions. But Seltaeb is a disaster only because everything else was a triumph on an unimaginable scale. Which Epstein helped create in innumerable ways — not least making sure those twin tigers, John and Paul, were both well-fed and taken care of. This is Management 101.

Klein, on the other hand, not only hastened the breakup of the group, he did much to make it irreparable. What does it say about Klein that his biggest clients kept leaving his management? Why did people who were (it seems) benefitting from his genius for forensic accounting (which is a skill, for sure), want to get the hell away from him? They all said he was a crook. So Fred Goodman, armed with Klein’s own files, is attempting to convince us otherwise? The guy had one trick — going over the accounts, and bullying big corporations — but every other aspect of his “management” seems to have been disastrously poor. Not because he wasn’t smooth or well-bred, but because he killed the goddamn golden goose! So he came up with the idea of turning “Get Back” into “Let It Be.” Better that he’d kept Paul happy and making Beatle records for one more year, two more years, five more years! Look at what John, Paul, George, and Ringo created from 1970-73; the amount of money Klein cost himself, simply by disrespecting Paul at every turn, and being an asshole towards the Eastmans, has to be in the $100s of millions. And why? Because John, in his junkie paranoia and shitty self-image, wanted to stick it to Paul. Insane.

Allen Klein’s actions are simply not those of a manager wanting to keep the Beatles together, so the question that must be asked is this: did Klein believe that he could make more money being the manager of John, George and Ringo separately — plus the manager of whatever entity they might form without Paul? There is a certain business cunning to this, even though it turned out to be utterly wrongheaded. It fits with his behavior, and his take-the-money-and-run style with his clients.

Rather than bending over backwards to rehabilitate Allen Klein, Beatles fans (and historians) need to start judging the man on the effects of his moves. Yes, he squeezed more money out of EMI, but what good is that if you split the group? The Beatles were, and probably are, the most profitable franchise in the history of popular culture. A merely competent manager would’ve done anything — anything — to keep them together and putting out music as The Beatles. Only a fundamentally unethical person who was too clever by half would attempt to control them by (mis)identifying the leader, and feeding his neuroses; and not for nothing was Klein’s greatest supporter that other person who attempted to control the Beatles via John, Yoko Ono.

You don’t control the Beatles; Brian realized that. You enable them to do what they do, and reap the benefits. That’s how everybody makes the most money, and in the end, that’s what being a good businessman is about. Right? Right.

Very well put, Michael. But I think that plea of insanity — or at least stupendous incompetence — must be leveled at all of them, Paul included. How could any of them think that they could make the magic without the other three? I think George either hated being a Beatle or hated himself (only a handful of songs are not sanctimonious homilies), and once he had a fucking castle (better publishing contract), he just didn’t care any more. Ringo genuinely wanted everybody to be friends. John had his Iago always at his ear.

But Paul — Paul just plain loved being a Beatle, it was his energy, his vitality. How could he not have gotten the message to quit telling them what to do in the studio? Yes, his nitpicking made the records better, sometimes incomparably — when John came in with Come Together it was a Chuck Berry tune. Paul slowed it down, made it swampy, created the sine qua non bass riff, and basically told Ringo how to drum it — but his perfectionism about the group was useless WITHOUT THE GROUP!

They really do seem, the four of them, like the stereotype of the ridiculously reserved Englishman. The three of them couldn’t sit John down and tell him “that’s it, enough, no women in the studio”. The other three of them couldn’t go to Paul and say “look man, your perfectionism is driving us crazy. You’re on probation for the next album.”

They are a Greek tragedy — we see it coming from a mile away, we see them ignoring it, from pride, or stupidity, or vainglory, or some other character flaw, until finally, as we knew it would at the beginning, it destroys them.

Greek tragedy is right, Sir HF. Have you read Doggett’s “You Never Give Me Your Money” and Gilmore’s “Why the Beatles Broke Up” in Rolling Stone? Those two accounts are the most fair-minded and comprehensive, IMO.

.

I think the tragedy is that John, Paul, and George stayed stuck in their respective dysfunctions, and that no one close to them was apparently able to help them slow down and rethink things. For example, I think Paul kept being pushy and perfectionistic because that’s how managed stress and uncertainty. John kept being passive-aggressive and latched on to Yoko and Allen Klein because that’s how he dealt with his deep insecurity and anger. And George was venting frustration with Paul and John that had been simmering for years.

.

I think Gilmore does the best job of analyzing why Paul finally lost it and went public with the breakup, despite his love for the band.

And herein lied the obvious role Brian Epstein played. We probably will never know the full extent of how much Brian assuaged egos, facilitated agreements, provided a sounding board for hurt feelings.

Gilmore’s a friend of a friend, if his book ever appears I’ll see if we can get him to come on and answer questions.

“Better that he’d kept Paul happy and making Beatle records for one more year, two more years, five more years!”

This, to me, was the book’s greatest failure: Goodman’s refusal to discuss or analyze Paul’s relationship with Klein. He blithely accepts the accepted wisdom that, because of Paul’s ties to the Eastman’s, the two were mortal enemies from day one. He never addresses the massive errors Klein made in his bullying approach to Paul, his terrible treatment of the Eastman’s, his overt preferences for John and Yoko, or any of those issues. Paul had already demonstrated that he would work hard for a manager — Brian — who favored John. But Klein’s initial approach regarding Paul is simply inexcusable. From the beginning to the end, Klein ‘handled’ McCartney in a way that seems as if he *wanted* to antagonize and alienate one of the two top-tier Beatles, the member who had written or co-written their best-selling and most profitable songs. And no one — not Goodman, not Doggett, not Gilmore — has ever asked “Why?”

If we assume that Klein was motivated by his own managerial and financial self-interest, his actions make no sense. Klein was capable of being charming, warm, funny, and encouraging trust, but we have no evidence — none — that he ever attempted any sort of charm offensive with Paul. Instead, we have accounts of Klein insulting Paul’s in-laws in front of Paul’s face, attempting to bully Paul into signing a contract — an event which Glyn John’s described as “very disturbing to witness,” and laughing when Paul threatened to sue. We have Klein — who is still predicting, in 1971, that Paul will “come back” in two years after he has extracted himself from the Eastman’s — bragging about helping John write “How Do You Sleep” in that same interview. You have Klein sponsoring Yoko’s art exhibits with Apple’s money and stroking John’s ego and declaring that “John had written most of the stuff” under the Lennon/McCartney catalog and referring to Paul as “the reluctant virgin” for refusing to blindly accept Klein’s financial decisions and refusing to take his calls, and yet when Paul quits and then sues, its evidently a complete and utter shock to Klein. Either Klein massively miscalculated Paul’s character and willingness to be bullied, or he simply didn’t care that his relationship with McCartney was abysmal.

“Allen Klein’s actions are simply not those of a manager wanting to keep the Beatles together,”

There are only a few reasons I can come up with for why Klein immediately adopted such an antagonistic approach to Paul. First, Klein knew, with the Eastman’s looking over his financial shoulder, that he’d never be able to pull a Nanker-Phelge on the Beatles. Lining his pockets wouldn’t work unless he discredited the Eastman’s, and discrediting the Eastman’s to John, George and Ringo included discrediting Paul.

Second, Klein believed he had Paul legally trapped in the Beatles contract, and genuinely didn’t care much about how abysmal their business and personal relations were with each other.

Third: Klein simply didn’t like Paul. Klein does complain in his 1971 Playboy interview that, despite attempts, he never got close to Paul, and I think there might be an element of truth to that: Paul was always the most reserved Beatle with outsiders. Everyone says that within an hour of meeting you, Klein could figure out your greatest desires and deepest fears, and played on that to establish a personal connection with you. Perhaps Klein simply couldn’t read Paul. Much of Klein’s managerial strategy seemed to hinge on that intense, personal connection between manager and client, and Klein did manage that with John, George and Ringo. He utterly failed with Paul.

Fourth, Klein wasn’t flattering John at their first meeting: he genuinely believed that “John had written most of the stuff” under the Lennon/McCartney credit. If Klein went into the Beatles believing that Paul was significantly less important to the Beatles than John was, that Paul was “replaceable,” his entire attitude towards Paul makes a lot more sense.

Fifth: Klein painted himself into a corner with his initial approach to John and Yoko by so clearly identifying himself in *their* corner. Backtracking on that — trying to bring Paul into the fold, publicly flattering Paul as he did John, attempting to establish better relations with Paul’s in-laws — would have weakened a major part of his initial appeal for J&Y: he was supposed to be their champion.

@Ruth, surely your suggestions are part of the picture, but there’s no need to go into psychology to figure out why Klein didn’t work harder to keep the Beatles together. He made the sound business calculation that, over the short term, more commissionable units would be sold by three of them working separately under his management, than by the group. This is pretty S.O.P. in the media/entertainment business.

And for a year, he wasn’t wrong. The aggregate 1970-71 sales of All Things Must Pass, John Lennon: Plastic Ono Band, Sentimental Journey, Imagine, and Beaucoups of Blues are very likely to be more than another Beatles album would’ve been — even one as successful as Abbey Road (five million in the first six months).

Looked at this way — from a simple short-term dollars and sense perspective, without foreknowledge of the 70s — suddenly it’s clear that a breakup was in Klein’s best interests, regardless of the best interests of his clients, or the world of music. This strip-mining approach is common — the Beatles would’ve encountered it with any manager that wasn’t emotionally attached to them as an entity, and after Brian, nobody would’ve been. Stigwood might’ve done the same thing. That Klein wasn’t smart enough to see that the Beatles were a multi-decade goldmine… well, not everybody can be as good a businessman as Brian Epstein.

I beat this drum, because it’s really a blindspot in Beatles history. Epstein’s name has been blackened by journalists and historians, applying simplistic and naive thinking. It’s one thing to say, “The Beatles were phenomenally lucky to get a man who cared about them deeply as their manager”, which every writer says, before talking about lost lunchbox royalties. It’s quite another thing to really acknowledge that, under someone like Klein, Beatlemania would’ve never happened in the first place, for lots of reasons. The Beatles’ commercial success was built upon the bedrock of visionary management, and later griping about Seltaeb — from Lennon especially — is merely about his greed, and a fantasy of being able to knock off work in June ’65.

But that’s not what would’ve happened, had Brian — that “lovely theatrical guy” — not been running things. What would’ve happened was a split in 1963 — “We gotta capitalize on ‘She Loves You,’ John!” — and three years later, “Ladies and gentlemen, introducing ‘Long John and the Longjohns,’ with their #17 hit, ‘Please Help Me Girl’!”

And three years after that, not the Bed-In, but the Boom-Boom Room in lovely Las Vegas.

Oh, and while I’m thinking of it: the “Brian-as-incompetent” meme is a not-too-subtle feminization of Brian.

Brian is gay, therefore feminine, therefore bad at hard things like business, and good at soft things like picking out the right suits.

More straight, white, cisgendered, patriarchal bullshit, if you ask me. Now, if you’ll excuse me, there’s a strange knock at my door… 🙂

“He made the sound business calculation that, over the short term, more commissionable units would be sold by three of them working separately under his management, than by the group. This is pretty S.O.P. in the media/entertainment business.”

That would explain a lot … but what about Klein’s loss of prestige? There are countless interviews, both retrospective and contemporaneous, that reveal how much Klein obsessed over getting the Beatles, and that the reason was they were the biggest show on earth. If Klein splits the band, severing McCartney from it in the process, he’s no longer the manager of The Beatles, a position he’d coveted for years.

@Ruth, this is kinda what I’m getting at with all this: don’t believe what people like Klein say. Believe what they do. He lies, manipulates, spins — this is why he’s good at his job. Looking to him to tell you what he’s really thinking is guaranteed to mislead.

Any kind of prestige Allen Klein wanted, could be bought. And once he had signed John/George/Ringo, he had all the prestige that position offered. Staying in the job offers diminishing psychological returns — as long as they are The Beatles. Obviously Allen Klein was obsessed with getting the Beatles — as I’m sure he wanted to get the Stones before them. But he wasn’t obsessed with keeping the Beatles, clearly — just as he wasn’t obsessed with keeping the Stones. Maybe he wanted to put his mark on the Beatles by making a McCartney-less group even bigger. Imagine how that would play with John. Or maybe not — I just don’t think the guy was thinking much beyond his own base desires. He’s certainly not thinking long-term.

Earlier in these comments someone talked about how Brian would referee between John and Paul. When Klein comes on the scene, he does everything he can to curry John’s favor, and nothing much to curry Paul’s. Either he’s not interested in keeping Paul happy, or he’s an idiot, and I think it’s clear he’s not an idiot.

Great review, Ruth. Thanks for writing it and for reading that crap of a book in the first place. The title alone is galling. In what alternate universe, devoid of historical fact, does the author think that will fly?

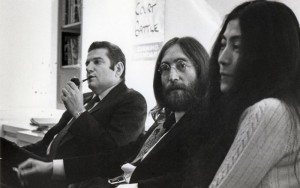

The picture of John with Yoko and Klein says it all: he was — holy God — John Lennon! But deep down, he was still the not-badhearted but gullible boy yearning desperately for a mother. My son lost his mom, my wife, in 2012, when he was 11, and I worry that he’ll fall for a woman who won’t respect him. I’ve thought a lot about it, and John Lennon seems to be a patient which simple Freudian analysis could actually cure.

But back to Klein. It’s the same story. Lennon was an artist, but that didn’t make him smart. His interviews reveal him to be dedicated to many half-baked, hare-brained notions, like “vegetarians don’t get cancer” and “Yoko and I should make records together.” Lewisohn’s bio makes it clear that even after Paul and George had decided they’d been screwed royally by the smooth and genial Dick James, Lennon was always happy to see him enter the studio. Ditto the Maharishi — I suppose that even a fellow as unsubtle as Ringo saw through the giggles; it was not only his stomach that wanted him to leave. But Lennon seemed oblivious.

It was because of, not in spite of, the fact that Allen Klein made it sound like it would be so easy to get them out of financial trouble, that Lennon was drawn to him.

It’s that naivety, together with little glimmers of humanity — how Lennon would invite people waiting outside his gates to talk with him in the garden, for hours, regularly — which make me think that, if you divorce him from his Beatledom, he might have been a decent guy. But he wanted so much to be controlled — his behavior with Sean showed that he could certainly love his children, which makes it one of Yoko’s greatest evils that she turned him against the son not her own.

I guess what I’m saying is, whatever the problem, it’s Yoko’s fault. A failed “concept artist” took the most successful popular musician in history, by a long way, and made him think his work was shit. By comparison, it’s nothing to make him hand the keys to Klein.

Cato the Elder was reported to finish every declaration he ever made to the Senate, whatever the topic with the words “this is my opinion. It is also my opinion that Carthage must be destroyed.” I can’t discuss the Beatles after Hey Bulldog without it turning into a diatribe against Yoko. Yoko Ono delenda est.

“I guess what I’m saying is, whatever the problem, it’s Yoko’s fault. A failed “concept artist” took the most successful popular musician in history, by a long way, and made him think his work was shit. By comparison, it’s nothing to make him hand the keys to Klein.”

That is the crux of it, IMO. And Klein knew how to get next to John: flatter Yoko and appeal to her ego. That was a pattern repeated over and over again until John’s death. How tragic.

Brian Epstein disliked conflict while Klein seemed to thrive on it.

.

If Klein truly believed John was the real creative force (and wasn’t just kissing John’s ass by saying so) is it possible he envisioned himself “managing” John George Ringo and [insert a Ronnie Wood/Mick Taylor-type replacement]?

.

Most HeyDullBloggers agree all four lads were not replaceable. But did Klein think that way? As a manager, I can imagine him growling “nobody’s irreplaceable, baby!” He saw Brian Jones fade away. Maybe Klein thought Paul would bow out and leave him in control of a new and “better” Beatles? (Klein: “Hey John, we can get Klaus on bass and the kids won’t know the difference!”)

This makes a lot of sense to me, @Sam.

But now I can’t get Long John and the Longjohns’ #17 hit, ‘Please Help Me Girl’!” out of my head…

.

“I love when you hold me so tight

Whisper in my ear:

Let’s you and him fight

Wooooh!

.

Please help me girl

I turned down Brian

And went with Klein

Let’s you and him fight

Wooooh!”

Chords, please, Mr. Innes

It makes a lot of sense … but it would require wilful blindness on Klein’s part. Brian Jones was no Paul McCartney: at the bare minimum, he couldn’t write songs.

One thing Goodman emphasizes is how obsessed Klein was with getting the Beatles: years before he was introduced to them, he would spend days and days doing nothing but discussing ways to get his foot in the door. He read every interview they gave, including the Authorized Biography, quizzed the Rolling Stones about them, and assiduously researched every piece of information he could find. That’s how he knew what pitch to take with John in the first place — to cater to John’s ego and declare his belief in John’s leadership.

All the evidence available to Klein at the time should have given him the exact opposite impression of “Paul as replaceable”: Paul was the one who had been writing most of the band’s singles since 1966; Paul had written their biggest number one and the majority of their billboard hits; Paul was the one with the closest working relationship with George Martin. There are numerous sources that argue that Paul was the most popular overall Beatle during the official narrative. How Klein could look at that evidence and even begin to believe that McCartney was replaceable baffles the mind.

How Klein could look at that evidence and even begin to believe that McCartney was replaceable baffles the mind.

Only if you’re keeping it The Beatles, @Ruth. And as long as Klein was managing the Beatles, he would have to share the spotlight with the ghost of Brian Epstein. Allowing them to split, making more money from John/George/Ringo all being solo artists, and then managing whatever supergroup Lennon could put together (remember this was the time of Blind Faith, etc), and arranging Stones/Zep-like mega-tours…You can see the logic. “It’ll be much bigger than the Cow Palace in nineteen-fucking-sixty-five, John! Screw Paul if he can’t see that!”

This scenario seems a lot more likely than Allen Klein being stupid — stupidly antagonizing Paul for no direct benefit; stupidly assuming that Paul wouldn’t sue; stupidly thinking that his own shady dealings wouldn’t prejudice the judge; stupidly thinking that he was so charming to keep the wool pulled over John, George and Ringo’s eyes even as all this was going on.

I think Klein had a plan. A so-smart-it’s-stupid plan. He’s the kind of guy that always does.

Ruth thanks so much for the review and all of you wonderful commenters. I’m enjoying every word. But Ruth one thing confuses me. You say Klein was not flattering John when he said John wrote all the stuff, that Klein actually believed it. Then you say that he had been watching the Beatles for years,reading every interview, and most likely keeping track of who wrote what and surely seeing that Paul was eventually writing their hits. So how could he be so well read on the group as you say, but think John wrote all the stuff. Forgive me someone already explained it and I missed it. I am reading this with one eye on the clock because I have to go to a wake.

“You say Klein was not flattering John when he said John wrote all the stuff, that Klein actually believed it. Then you say that he had been watching the Beatles for years,reading every interview, and most likely keeping track of who wrote what and surely seeing that Paul was eventually writing their hits. So how could he be so well read on the group as you say, but think John wrote all the stuff.”

Sorry I wasn’t clearer, linda. My theory that Klein wasn’t flattering John at their first meeting — that he actually believed “John had written most of the stuff” — is speculation, not fact. Its based off of Klein’s 1971 Playboy interview, where he declares that John wrote most of the Lennon/McCartney catalog and reveals that he was the one who ‘reminded’ John, at that first meeting, that John had written most of “Eleanor Rigby.”

Either Klein knew otherwise and was flattering John to get on his good side, or he honestly believed that was true. If he believed it, his rotten treatment of Paul makes a great deal more sense, given that he would have viewed a vastly inferior Paul as replaceable … but given the massive amount of research Klein had done on the Beatles, it seems incomprehensible that Klein genuinely believed this. So both theories contradict each other.

Well to me given that Klein certainly did know otherwise, it seems he was probably trying to flatter John in the interview. I don’t see how he could have actually believed that unless he was delusional. I think he just knew how to manipulate John by flattering him. I mean, where on earth would he have gotten the idea that John wrote 70% of Eleanor Rigby? He just made it up because he picked up on the competitive tension between Lennon and McCartney and he knew exactly how to manipulate that using one of their biggest hits. Or did he perhaps think that Paul was merely some sort of figurehead and John was actually the brains behind every song and Paul simply took the credit for some of them?

Hi everyone

—

Couple of things.

—

I went to a talk given by Mark Lewisohn in London last night – Tune In has been published in paperback, so he’s been doing the rounds. He said two things that he’d just discovered, one of which really made him sit up and pay attention. One was that Epstein and Klein definitely met in 1965, the other was that the Beatles came “within a hair’s breadth” (I always thought the phrase was “hare’s breadth” but Google tells me I’m wrong) of meeting Klein in 1965. He said it never happened, and he’s either holding on to more info for volume 2 or he genuinely doesn’t know any more yet. But it was a real surprise to him.

—

I think it’s more than possible that Klein genuinely wanted the Beatles – as Lewisohn said, he’d wanted them since 1965 – in a genuine but totally naive way, thinking only in his twisted business terms, and then when he finally got them, realised things might be falling apart, didn’t have the psychological makeup to be Brian Epstein (again, quoting Lewisohn from last night, they needed a manager who wasn’t going to tell them what to do, but was going to just let them be them be Beatles, presenting real options to them and guiding them gently, as both he and George Martin did so fantastically) – and thus, seeing dissent and tension, moved towards plan B, described above so well: make as much money now from solo Beatles, cos this Beatles thing is over.

—

The second thing is about this “You’ll stay on the fucking label, Hare Krishna” quote. It comes from Paul, but the one thing that always comes across to me, right from Paul’s childhood, is that he needs to defend himself by making other people look like the bad guys. He uses half-quotes, or he tells you what he wanted to say and makes out that he actually said it, or like here, he doesn’t give you any context. Or he starts the story half way through when he assigns blame.

—

With a quote such as this, we MUST ask “Is that it? Did nothing lead up to this point? Does it mean exactly what Paul wants us to think it means?” What I’m saying is, knowing George’s propensity towards sarcasm, isn’t it possible to imagine that he wasn’t being shitty but was playing with Paul? Like, “You’ll stay on the label forever and ever and ever”, like “Haha Paul, things may have got better between us [if my memory is correct, relationships were a lot better right around this time] but we are going to be bound together til the end of time *wink*”.

—

Given the description of the meeting as amicable, I don’t think it necessarily follows that George was being nasty to Paul. Paul has a real ability to make out that people did and said bad things to him – witness how he was really late for a gig with Epstein as manager early on, leaving them to wait outside’ they passed a message that they were going into town for a drink and would come back – and when he saw that they hadn’t waited for him, he refused to play the first gig. His version of the story is that “they couldn’t be bothered to wait for me, so why should I do anything for them” ignored the fact that he was late in the first place without notice and was being awkward. That’s typical of how he operates: if you start the story half way through, then yep it’s the others’ fault. So that’s the story he tells.

—

When Paul is the only witness, I think we have to carefully think through what he might NOT be telling us. In this case, the “fucking label” comment flies in the face of what else we know about this specific period. It has never made sense to me, and so I ask “what might have happened in the 2 minutes before this, to make George be so nasty?” Until I have an answer for that, I’m not going to being George was being nasty OR nice, because I simply don’t have enough evidence to go on.

—

I think it’s a crying shame that Paul has never changed this aspect of himself – Lewisohn said last night that even right up til now, if you tell Paul not to do something, he’ll go right ahead and do it. It means the most vocal witness is the most unreliable one. With John, you couldn’t trust what he said from month to month, but you could piece enough together to make a truth. With Paul, I always have to run it through what I call my “Insecurity/Passive-Aggression Filter” – I used to be very much like Paul as a kid, and I can *feel* that covering up, that twisting of the story, that goes through every anecdote he tells.

—

As a character, John is the most fascinating Beatle. But I find Paul far more interesting psychologically. He’s never been studied the way John has. It’s vital though – understanding what lies behind Paul’s perfectionism, his unwillingness to bend, his desire to have everything done his way (he was right about George’s guitar idea for Hey Jude being awful though – it changes the whole song, makes it terrible), his willingness to feel *so* superior, he will drive his band into the ground to get Maxwell’s Silver Hammer recorded. He’s much more complex than John even, in my view, because he completely hides his emotions and you have to work out what he *isn’t* saying before you can understand what he tells you.

” . . . the one thing that always comes across to me, right from Paul’s childhood, is that he needs to defend himself by making other people look like the bad guys. He uses half-quotes, or he tells you what he wanted to say and makes out that he actually said it, or like here, he doesn’t give you any context. Or he starts the story half way through when he assigns blame.”

.

evilpants, I agree that Paul often does this — but I don’t see much difference between what you describe Paul doing here and what John frequently did in interviews. John explained “How Do You Sleep?” by pointing to Paul’s digs at him on “Ram,” but didn’t acknowledge the extremely negative things he’d been saying publicly about Paul before “Ram.” John complained about George not talking about him in his autobiography, but didn’t acknowledge that the way he’d treated George might have contributed to that decision. John complained about the way the other Beatles treated Yoko, but didn’t acknowledge his unfairness in foisting her continual presence and feedback on them in the studio the way he did. And so on. I think Lennon and McCartney are more alike than they are different in their need to spin the story — but John’s emotional rawness reads as sincerity, while Paul’s insecurity reads as passive-aggression. I don’t think we can trust what EITHER of them says to be the whole truth.

.

“I think it’s a crying shame that Paul has never changed this aspect of himself – Lewisohn said last night that even right up til now, if you tell Paul not to do something, he’ll go right ahead and do it.”

.

Now this I can agree with, although given how hard it is for non-famous people to do that kind of work on themselves, how hard must it be for spectacularly well-known ones who are often the target of others’ disdain and anger? Post-1980, Paul really got put through the public shredder — and that followed his getting blamed for the band’s breakup. It’s not surprising to me, although it’s depressing, that he’s held on to his defense mechanisms. And I think the same kind of thing is true of Yoko: she could probably be much happier if she let go of her need to constantly control her public narrative, but she’s taken enough abuse that it’s hard to see that happening.

“The second thing is about this “You’ll stay on the fucking label, Hare Krishna” quote. With a quote such as this, we MUST ask “Is that it? Did nothing lead up to this point? Does it mean exactly what Paul wants us to think it means?”

—

I agree that more context regarding this quote and the entirety of the Harrison/McCartney conversation would be extremely valuable, and with much of your analysis regarding Paul’s selective memory — although, as Nancy notes, both John and George were also guilty of highly selective memory as well.

—

My issue with the absence of the “You’ll Stay on the Fucking Label” quote in Goodman’s work wasn’t so much the lack of context (no one really offers insight into the rest of the conversation, not even Doggett) but that Goodman doesn’t even acknowledge that Paul claims George said it. He claims the meeting was amicable while omitting primary source evidence arguing that it was anything *but* amicable, a pattern of omission that he commits at various other instances in the book in order to further his thesis.

—

Even if you’re right and George did it mean it in a joking/sarcastic/non-cruel way, and that Paul is only providing half the story, its clear that, by MYFN, that’s not how Paul regarded it: he saw it as George putting his foot on Paul’s throat. If Goodman’s work is supposed to be accurate and/or credible, he can’t offer an interpretation — the meeting was amicable, with a good chance that all four Beatles could meet in January and resolve the massive Klein fissure — while ignoring the only primary source evidence we have — which directly contradicts his interpretation — by arguing that George said something vicious. He can evaluate it, as you did, by mentioning George’s well known-tendency towards sarcasm, or by examining the state of Paul and George’s relationship at the time, but methodologically he can’t ignore it, which is exactly what he does.

—-

Its also worth noting that, while Paul is the only source we have for this quote, he said it several times while George was still alive and capable of refuting Paul’s statements: I know its in MYFN, and it might even be in Anthology. But George never disputed Paul’s words or offered more information regarding that particular meeting. I desperately wish someone had taken notes and/or recorded it, though.

“It comes from Paul, but the one thing that always comes across to me, right from Paul’s childhood, is that he needs to defend himself by making other people look like the bad guys.”

*

I don’t see how this is particular to Paul. Every human being does this to some extent — including all of the Beatles.

*

Attributing this quality only to Paul is yet another example in the long history of making Paul the villain of the piece. And this comment that “the most vocal witness is also the most unreliable” is nonsense. Sorry but it is. Paul is no more or less biased or unreliable than John.

“He will drive his band into the ground to get Maxwell’s Silver Hammer recorded.”

*

This comment seems extremely unfair, too. George Harrison did more than 100 takes on that middling song, Not Guilty. Isn’t that an example of someone being willing to drive his band into the ground to get Not Guilty recorded? And of course, it never even ended up on a Beatles album. Paul wasn’t the only one obsessed about getting his songs just right. George was, too. And the only reason John wasn’t was because he didn’t have the patience for endless takes.

*

I just think we need to be careful before ascribing all of these negative qualities to Paul alone.

I’ll go you one better, Drew — I think being absolutely focused on making the final product as great as it can be, is exactly what makes a genius.

One of the many ways that Paul gets unfair treatment in regards to John is the idea that genius is effortless — what one is — rather than what one does. Do people criticize Frank Lloyd Wright for doing architectural plans? When it comes time to build the building, should he just let the builders finish the last 10% “as they feel”?

The other Beatles benefitted from Paul’s perfectionism on all of their tracks. And it’s telling that this wasn’t an issue in 1966. It’s only in 1969, when Lennon’s on the nod and not-so-subtly hates the group (and is pouring poison into George’s ear — that what “I did everything you said” was about), that Paul’s perfectionism suddenly becomes a problem.

Paul’s probably hell to work with, and for (if you’re recording one of his songs). But by ’69, he’d more than earned the right to get things done the way he wanted.

Agreed, Michael. What’s especially bizarre is that — in fact — the band took only THREE sessions to record Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. It wasn’t a long time or a lot of takes. So the others didn’t like the song? So what. I can think of far worse jobs in life than to have to record for 2 or 3 days on a song you don’t like. Cry me a river.

*

The reaction to the song is totally blown out of proportion — the way all sorts of things get blown out of proportion just because it’s the Beatles. For most bands, this minor track would be something people who go “well I don’t much like it” and forget about it. With the Beatles, it becomes a stick with which to beat Paul with — over and over for 50 years — for all sorts of imagined sins.

Disliking Paul — or at least parroting John’s best-known jabs — is a way for some fans to show that they have taste as good as John Lennon’s. It’s a way to be more Catholic than the Pope.

Also: take numbers aren’t full takes, right.

Michael – if you have the time and energy, please could you add empty paragraph lines in my comment? Thanks! I forgot that this WordPress theme strips them out. I offered to help a few months back – ill health has prevented me from doing much, but I’d still like to help with a couple of blog problems, the spacing being one of them. It’s actually a problem with the theme you’ve got, and you need a few lines of code added (or removed) – it’s a clean job, we just need to find where the code strips out the spaces and remove it, or add some code to read and preserve space. The downside is, they don’t sell this theme anymore so I can’t get it and check the source code. I did look for it back in September. I might contact the theme author, because I’d be willing to bet their themes are all based around the same core code.

Tony, let’s talk about this further. I’m sorry you were not feeling well, and hope you are totally healed. I have my own experiences with that.

Maybe we should just update the theme…?