- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

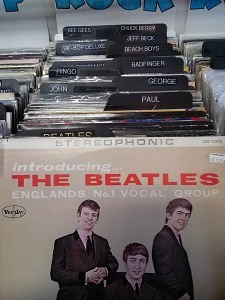

NANCY CARR * The Beatles broke up over 40 years ago, but in the public’s mind they could never really stop being Beatles. The desperate efforts of all the band’s members (well, except Ringo) in the 1970s to escape its gravitational pull were doomed. If you want to see this reality in action today, check out the displays in a nearby record store—assuming you’re near one that’s survived. There’s a good chance that everything Beatles related will be shelved together.

One of my favorite local shops, Oak Park Records, is owned by Alan Heffelfinger, who’s particularly knowledgeable about music (he worked for EMI distribution before opening his store, and writes and plays music himself). So a few days ago I asked him something I’d been wondering, Beatles freak and record geek that I am, for some time: in his bins, why do solo records by Paul, John, George and Ringo follow the Beatles section?

John: “I can’t believe we’re STILL STUCK TOGETHER!”

Ringo: “It’s not so bad, really.”

George: “Hey, at least Paul’s not hogging the spotlight in this picture.”

“Not a lot of people come in looking specifically for a John or Paul album,” Alan said. “They’ll come in thinking ‘I’m going to look at the Beatles stuff, and at some solo stuff.’ It’s really a matter of convenience. Being in the Beatles defined them. It’s like Elijah Wood playing Frodo in the Lord of the Rings movies, or Henry Winkler playing the Fonz. It doesn’t matter what else they do, they’ll always be known for those roles. No matter what John, Paul, George, or Ringo did, they were always one of the Beatles.”

In other words, John’s insistence that he didn’t believe in the Beatles, Paul’s inclusion of the infamous copulating-beetles picture on the back of “Ram,” and George’s insistence that the Beatles experience was a bummer weren’t enough to keep them apart in (what remains of) the music-buying crowd.

“The Beatles” as a black hole with a extensive event horizon

This tendency of “The Beatles” as a category to pull its former members back in extends well beyond them. Often the “John Lennon” section includes Yoko Ono, Julian Lennon, and Sean Lennon. I’ve seen it rope in Harry Nilsson’s Pussy Cats (which Lennon produced), and David Peel’s Bring Back the Beatles. The “Paul McCartney” section virtually always includes the Fireman and all manifestations of Wings, along with an occasional Mike McGear or Denny Laine solo album. As for the “George Harrison” section, I’ve seen it include Ravi Shankar, The Concert for Bangladesh, the album Goddess of Fortune, and sometimes The Traveling Wilburys.

And that’s not even getting into all the “Beatles-related” albums that can show up in the bin: the Hollyridge Strings’ myriad cover albums, Beatlemania exploitation records like the Buggs’ Beetle Beat and Murray the K’s The Fifth Beatle Gives You Their Favorite Golden Gassers.

I suspect that most shop owners, if asked about the reasons for this lumping together, would give an answer like Alan’s: the Beatles are such a big draw that if you’re a musician who gets close to them, you’ll be defined by that association, at least commercially.

You can sell the Beatles’ work all of the time, the solo work some of the time

When I asked Alan how sales of Beatles records compare to what they were ten years ago, he said “They’ve always sold like crazy.” He added that while the vinyl reissues are popular, especially among kids just getting into the Beatles, “the collectors want the originals. Even the 1980s issues are becoming more popular. We’re celebrating 50 years of the Beatles, so a lot of people would rather have something that reflects that time than something new.”

The Beatles new albums that sell most readily are (no surprises here) Abbey Road, Rubber Soul, Revolver, and Sgt. Pepper’s.

The solo work doesn’t sell nearly as much. Alan said McCartney’s work probably sells the most in this category, but that may be because there’s more on offer. That’s also the reason for the un-iconic “Paul, John, George, and Ringo” order of the solo work. “Since Paul has the biggest solo catalog, he’s first because it looks better to have more records after the Beatles section.”

But the solo album Alan gets the most requests for is All Things Must Pass. Plastic Ono Band, Imagine, and Band on the Run are all fairly reliable movers. Interest in Ram has picked up in the past few years, as that album has gotten more critical attention. Alan remarked rather sadly that “Ringo doesn’t sell, but the Ringo album is one of the best Beatles solo records. It’s really an all-star cast.”

Picking favorites in the solo catalog

The solo album Alan listens to most is All Things Must Pass. “I enjoy most of George’s stuff, except for Gone Troppo. For John, I love Mind Games and Walls and Bridges, maybe because I’ve heard them less. I think of stuff like “Freda People (Bring on the Lucie)”—there’s a lot of good songs that didn’t get much attention.

“I listened to Wings Over America a lot as a kid—partly it was just fascinating to be able to fold the sleeve out and have three records plus posters! But it’s also musically cool. I still enjoy it. With Paul, my enjoyment of him has gone up over the years. My daughters [ages 10 and 8] love him, so I’ve been listening to him a lot. Even something like Press to Play I’ll listen to and think ‘Man, why are people dogging on this album? Half these songs are good!’ Paul’s kind of like the new Gershwin: he writes classic songs. Some of them are cheesy, but they’re damn good songs.”

Leaving the store, I look again at the Beatles section and wonder what John, Paul, George and Ringo would say about being shelfmates for eternity. At least Paul and Ringo have had time to broker a peace with the band’s legacy; Paul, in particular, clearly relishes doing live performances of Beatles songs that were purely studio creations. I’d like to think that even John and George would see this bin-sharing situation less as an aggravation and more as a testament to just how enduring their work with their bandmates has proven.

Great post, Nancy. I used to buy records here constantly during the 80s; I remember when it opened. It’s where I bought “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” (or maybe that was Gramophone Records on Clark St) and the 12″ of “Blue Monday”. After the glut of post-Barrett, post-BBC Beatles stuff died down in the mid-80s, my listening went like this: First I’d hear it on WXRT’s “Rock Over London”; then if I heard it at Medusa’s club, I’d buy it used at Second Hand Tunes. That was a GREAT strip of stores; I spent several afternoons a week in a used bookstore on the corner of OP Ave and South Blvd.

What do you think of Val’s Halla? (Full disclosure: I went to high school in Oak Park, and 85% of my family still lives there.) Val’s never had bootlegs, which was what I craved–though I think I did buy some comedy records there. She was an incredible grouch, but you couldn’t beat that tiny little store right by the El for ambiance. Never been to the new location.

My local vinyl shop–Record Surplus on Santa Monica and Centenela–racks ’em this way, too. I can’t remember a record store doing it differently. I feel it must be said: none of the solo Beatles had enough cultural impact to emerge from the shadows of their own past–while the 60s are epitomized by Beatles music, the ’70s really aren’t by Beatles solo tunes. (With the obvious exception of Double Fantasy as “the end of an era”.) The dominant context of solo Beatles work comes from its place in the continuing story of the Beatles, not on its own impact on the culture. And before you say that this was inevitable–that they had to run out of steam sometime and let others carry the flag– remember that the Beatles’ last record is one of their most impactful. As of 1969-70 there was no indication that they weren’t still at the pinnacle of their profession, and still driving the culture (often in weird ways–witness “Paul is Dead”).

I think if you’d given Lennon a crystal ball and shown him in 1968-69 what the 70s would hold for each of them, I think he would’ve found a way to stay a Beatle. His actions during the breakup are that of a man who assumes that he’ll have a solo career of the same magnitude as he’d had–and it was clear by ’72, if not earlier, that this was not going to happen. I think a lot of John’s Double Fantasy-era disdain for “the business” and “teenyboppers” is ill-hidden resentment over being lumped in with people like Paul Simon (and rightly so). “Go jack off to the Rolling Wings” is an acknowledgment that he hadn’t ruled the charts for a decade, and no longer had any idea how to do that. And his pre-assassination positioning of Yoko and himself as rock for people who’ve grown up–once again, see Paul Simon–is as much about market positioning as creative content.

Paul’s 70s career was the biggest of all of them, and plenty big, but not nearly as big as any of the large acts going then. Measured against Zep, Bowie, Elton, KISS, Queen, The Eagles–after ’73 or so, good solo Beatles were well-respected sellers, in an age of absolute Monsters of Rock. What the Beatles did by breaking up was splinter a HUGE following into several smaller, but still substantial, fanbases. And I’d argue that the vacuum created by the Beatles’ breakup was filled by lots of groups of much lesser talent; and that this is where much of the cultural malaise of the 70s came from. You see it in comedy ten years later.

Michael, the store changed from Second Hand Tunes when Alan bought it in November 2004. (The last Second Hand Tunes location, in Evanston, closed a few months ago.) He’s improved the stock (IMO) and also moved the focus more to vinyl than CDs. I’ve gotten some great recommendations from him; one of the most recent was Paul Pena, who wrote “Jet Airliner.” His “New Train” album was only recently released, though it was recorded back in the 70s, and it’s excellent.

In addition to Alan’s shop, I regularly hit up Old School Records in Forest Park, Dusty Groove in Wicker Park, and the Jazz Record Mart and Reckless Records in the Loop (which I think of as “Reckless Spending,” in my case). We’re spoiled with record stores in the Chicago area, compared to too much of the rest of the country.

I also wonder what Lennon would have done in the late 60s if he’d been able to see what the post-Beatles years would bring. Whenever I read interviews with him I get the feeling that he’s talking partly to convince himself, so I never quite buy his insistence that he didn’t regret the breakup. Similarly, he’s so adamant about how happy he is with Yoko that it makes me suspicious. When people are really that delighted with someone/something, they don’t have to keep reiterating that they are, in my experience.

One of my favorite solo Beatles lines is Paul’s “I go back so far / I’m in front of me” (from “The World Tonight,” on “Flaming Pie”). That’s the inescapable reality, for all four of them.

It’s the same in Germany (and Austria, or at least the one 2nd hand music store I’ve been to in Vienna) – although shop owners’ knowledge concerning albums George produced may not be quite as encyclopedic here.

This being The Official Year of George (and Ringo), is there perhaps any way of implementing some sort of concerted action to get stores to highlight “Extra Texture” as a “lost” masterwork? It could become the new “Ram”! There could be online petitions to have it re-released in a variety of Super (“Extra”) Deluxe Editions (which would include “You” as done by Ronnie Spector and a 20-minute “work in progress” section on “The Answer’s At the End”)! And once that’s been accomplished, we’d move on to “Ringo’s Rotogravure”! 🙂

The biggest solo seller is (still?) All Things Must Pass, I luv that, because it puts the work of George solo artist in clear perspective. ATMP is both a critical and a commercial succes, and that is cool. Honoring the work of George is still not easily triggered. Recently we hade the congrats posting to George’s whatever and we fans ended up discussing the psychological infouence of The BEATLES and how greaking up was a hard thing to…

Just taking a look at the solo Beatles’ platinum selling albums and yes George has the best-selling album in All Things Must Pass. It’s gone platinum 6 times. However, George only has one other album that went platinum (one time) and it’s Cloud Nine.

Paul, by contrast, is a platinum juggernaut. His best selling-album is Band on the Run, which went platinum 3 times. But his solo debut, McCartney, went platinum 2 times. And two of his greatest hits albums (All the Best and Wingspan) went platinum 2 times, and so did his live album, Back in the U.S. In addition, here are the following albums of his that went platinum once: Ram, Venus and Mars, Wings Over America, Wings at the Speed of Sound, London Town, Back to the Egg, Tug of War, Pipes of Peace, and Wings Greatest.

WOW.

I think the tendency of casual George fans is to think his best album is All Things Must Pass and that’s all you need, and I tend to agree with that. But Paul fans, casual or obsessive, are split over which is his best album. I would say it’s Ram but others say Band on the Run and still others would pick many of his others.

How did John do on the platinum front?

John’s best selling album is one of his mushiest (IMO) and not his best work by far. Double Fantasy is 3 times platinum. Imagine is 2 times platinum. John’s sales while he was alive were modest (by Beatles standards; it’s no wonder he resented Paul’s 70s success so much). John’s 1982 greatest hits, The John Lennon Collection, is 3 times platinum. His 1997 greatest hits, Lennon Legend, went platinum once. This is why people, with dark humor, say that death is a good career move.

George wrote one massively popular and highly acclaimed album in his life, which is sweet. But don’t people realize that most of those songs were helped by John and Paul? He was writing that album with the beatles, probably hoping to get most of those songs on Abbey Road or Let it Be. Should it surprise anyone that after he left John and Paul’s orbit he never again came anywhere close to the success he had with ATMP? Not me. I’m sure I’m generalizing a bit bc j/p didn’t help every song, but you get my point. They were around just long enough to sprinkle some of their magic-genius-dust onto ATMP and then Poof! they were gone and so was George’s ability to write a coherent and successful album.

Ahem. I’ve said it before (incl. upthread) and I’ll say it again: “Extra Texture (Read All About It)” is a momentous record and, to say the least, significantly more listenable than the stuff Paul and John were peddling around that time (I guess it’s predictable to single out “Magneto and Titanium Man” for ridicule, but there you go). “The Answer’s At the End”, “You”, “World of Stone”, “Grey Cloudy Lies” etc. wipe the floor with “Rock Show” (which I still kind of like), “Call Me Back Again”, “Spirits of Ancient Egypt” and, of course, that covers album John felt he had to make. Its only un-amazing feature is that it’s not a double album. Rant over!

Are you kidding? The only thing good about Extra Texture (Read All About It) is that OHNOTHIMAGEN stopped going on and on about Krishna in his song lyrics.

George called Extra Texture the worst of all his albums: “a grubby album … The production left a lot to be desired as did my performance.” (quote cited from Alan Clayson biography of George Harrison, p. 348)

Hi! No, I’m not kidding. Why would I be? Artists are hardly ever the best judges of their own work – that’s why every singer/group ever goes on and on about their current albums being “totally the best thing I/we’ve ever done”, and why I try not to listen too intently to that sort of stuff, or to care about chart “performance”. I’m sure George thought that putting out “ET” sounding like that was a good idea at the time or he wouldn’t have done it, so why the revisionism?

I agree, however, that one of the reasons why “ET” is so great is the complete absence of Krishnababble, which makes big chunks of “LITMW” unlistenable to me. In fact, I think that the albums George put out just before and after “ET” are mostly boring, while “ET” stands out like a sparkly lighthouse in a sea of grub. Yes, it’s “smooth”, synthy soft rock, but I’d rather have that any day than songs co-written with Ronnie Wood, Cole Porter cover versions, or “Try Some Buy Some”.

Guys, I must admit that I’ve never listened to Extra Texture as an album, only heard the songs. But I’m listening to it, and liking it.

In general I try not to hold a solo Beatle’s obsessions against him–and frankly I think that the absence of any similar repeating ideas in McCartney and Starr’s 70s work is why it often feels lightweight (and why Paul got slagged so relentlessly). George and John seemed to use their solo work exclusively to express themselves as individuals (cool), while Paul and Ringo were solely performers (uncool); but of course it’s the mix of the two that makes the Beatles stuff so much more fascinating. For example, I probably prefer Tug of War over Venus and Mars simply because I actually hear Paul’s life in “Here Today,” whereas “Rockshow”…after “Sgt. Pepper” and “MMT,” it’s just another McCartney opener. It’s like watching Michael Jordan practice; neat, but he’s better in an actual game.

I can mostly listen past the Hindu spirituality in George’s stuff when necessary, and mostly the same for John’s Yoko obsession. The difference being that George’s God-stuff can usually be universalized without much problem, whereas that’s much more difficult to do once one has really read about John and Yoko’s relationship. Or maybe it’s just that I have more tolerance for the concepts of Hinduism than the concepts of Yoko Ono! 🙂

As to George’s opinion of ET, be sure to factor in that he was at a personal and professional nadir at the time. I’m sure listening to it brought up all sorts of unpleasant memories and probably even physical sensations for him. If music is evocative for us fans, think of how much more so it must be if you’ve written, arranged, played on and sung a song.

Magneto and Titanium is a GREAT song. No offense but you’ve got be a little humorless about music not to appreciate what a great song it is. It’s FUN. Nothing wrong with that. And yes, George H was right: Extra Texture is awful.

And Michael: I’m sorry but if you seriously think Paul doesn’t express himself as an individual in his solo work then you can’t be listening very carefully. His work is filled with personal songs. I thought Ram alone made that pretty clear. I find that people don’t take Paul seriously lyric wise because they choose not to, not because he’s not being confessional and revealing. He is but you’re just not expecting him to be so you don’t listen to his songs for that.

@Drew, one of the reasons I like RAM by far the most of all McCartney solo work is that the personal content is much closer to the surface. And I love songs like “Dear Friend,” which is lovely AND gives me some sense of the person behind it. Hell, I even love Paul’s huge hits–“Another Day,” “Silly Love Songs,” “Listen to What the Man Said,” “With a Little Luck,” “Coming Up”–I’m not bashing the guy. But all of those songs, fit completely within the persona that Paul had staked out for himself from 1963 on. They are Old Showbiz, and that’s OK. But just like say, Cole Porter, if craft’s what you’re selling, only your very best will survive and be remembered. If on the other hand, your songs are the record of your life, as John’s were, they can be remembered as great songs AND/OR your life story.

As stated on this site ad infinitum, McCartney’s stance towards his audience is more distant, more guarded, more coded than either Lennon’s or Harrison’s was. It’s probably the same for his Beatles work, too–but as with Lennon and Harrison, once he’s on his own, quirks become flaws. When those flaws are compensated for–when Lennon bares his soul AND provides enough fully fledged musical ideas; when Harrison isn’t producing too much and supplementing his own work with talented sidemen; and when McCartney actually has something he wants to communicate via all his songcraft and melody–then the solo stuff is worth paying attention to. “Magneto and Titanium Man” is a perfect example of this, @Drew–sure it’s a fun song, but in a world full of great songs, even great McCartney songs, why spend even a second on that? If you like it, great. To me, it’s minor–and to me, most Beatles solo work is so incredibly minor compared to their work together that often the flaws are all I hear.

Paul has some great solo work, and some that is cringeworthy. His diehards can’t accept that. They think even his unreleased (for a reason) songs are masterpieces and Splies Like Us has redeeming qualities. His misfires aren’t garbage; they are “fun”. It’s also hilarious when Paul fans accuse John of being mushy and sentimental on Double Fantasy. Yeah, it’s because he’s dead that people like his greatest hits compilations.