- Memories of Nicholas Schaffner and The Beatles Forever - January 4, 2026

- Old Draft: Beatles Folk Memory 1970-1995 - December 8, 2025

- Lights are back on. - December 8, 2025

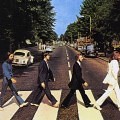

An outtake from Abbey Road (the cover, I mean)

Dullblogger Ed (come back Ed! we miss you!) shared a link this morning: Nik Cohn’s original review of Abbey Road for The New York Times. I always find hot-off-the-press reviews like this really interesting; for one thing, they give us a sense of how differently now-iconic bits of culture were seen at that time, which not only demonstrates how changeable things are—that there are pieces of work truly more in tune with a past or future than their time of creation—but also give us a clue as to how the texture of living in the past might’ve been genuinely different than it is today.

From our perch here in the unassailable present, we have an unflattering tendency to look down on the past. People then were just like us, we think, only maybe a little stupider; benighted, to be pitied, certainly impoverished without all the neato things that we in our wisdom have muscled into being and now consider necessities. But the reality of that moment was as complex as this moment, and past-living was just as full and challenging and rich. Somehow they managed without iPads, and Angry Birds…and so we might too. Reviews from the time can be glimpses of that truth, and turn the present into a choice, not a fait accompli.

Thumbs Down from Nik Cohn

Cohn doesn’t much like Abbey Road, which is of course surprising, and makes me think that the pre-punk 70s must’ve gone very hard for him. His reverence for 50s rock is referenced constantly—but ignores the pre-Pepper (shit, pre-Beatles) creative thinness and lack of emotional range of that genre, probably because he was a kid when it came out and he liked it so much he became a rock critic.

For example: winding himself up to praise the sound of Abbey Road, Cohn says ” the Beatles know as much about recording as anyone outside of Phil Spector”—but of course this was before several more decades without any appreciable effect on pop music (1972-present) revealed Spector to be simply an artifact of the early 60s. Phil Spector’s the music equivalent of the Brooklyn Dodgers, and like a lot of New York-generated culture, over time there turned out to be a lot less to him than we were led to believe. He clearly benefitted from the Youthquake, and being someone people like Tom Wolfe could understand (or think they did) and use as a symbol. John Lennon bought the hype, too, so I can’t be too hard on Nik Cohn.

But back to Cohn. here’s Cohn’s diss of “Come Together”:

“You Can’t Catch Me” is a very great song, after all, and lumbering it with the kind of “Look Ma, I’m Jesus” lyrics that Lennon unloads here is not a crime that I’d like to have on my conscience.”

But you’d rather live with thinking “You Can’t Catch Me” is a very great song? It’s not even Chuck Berry’s fifth-best song, and Chuck Berry (like Spector) turned into a nostalgia act the moment the Beatles touched down at JFK, which should’ve been obvious to anybody counting the crowd, much less listening to the music. But that is how differently Nik Cohn saw rock music in 1969, than we do today; and how different, perhaps, living in 1969 was from living today—”You Can’t Catch Me” was remarkable and “Come Together” wasn’t. Wow.

Cohn’s review also showed a moment where our greater knowledge of The Beatles story is an enriching thing—how the context we know now allows us to see them more clearly, more fairly. Bashing the lyrics on the album, Cohn singles this out for particular derision:

She came in through the bathroom window,

Protected by a silver spoon

But now she sucks her thumb and wanders

By the banks of her own lagoon.

Cohn thinks it a dollop of lyrical pap typical of the McCartney school, when in fact it was Paul simply describing something that happened to him (or someone). Because Cohn doesn’t trust McCartney to tell the simple truth, he looks for something else. That he doesn’t find it isn’t Paul McCartney’s fault.

At some important point Cohn simply stopped listening to Abbey Road and started building a case that it wasn’t as good as (cough) 50’s rock. He mis-attributes the vocal on “Oh Darling” to John, and dismisses it as “trying too hard”:

“‘Oh! Darling’ is more complex. Basically, it’s just a 1950’s ballad, the kind of thing that the Platters or the Penguins might have done. Lennon has always had a terrific voice, and here he halfway tears his lungs out. Just the same, it doesn’t sound right. Why not? Just because he tries too hard.

Oh! Darling—if only The Beatles had been The Platters or The Penguins, then they might’ve really amounted to something. Why did people listen to this man’s opinion about rock music? Why did this appear in The New York Times? Weren’t there other writers, y’know, paying better attention?

Here’s why:

As I read this review, I realized that Cohn’s blindspot—his belief that 50s rock was the be-all end-all template—wasn’t a bug, it was a feature. His not-getting-it was what The Times wanted in a rock reviewer—a British guy who loved Chuck Berry. Just as Ben Greenman’s review of McCartney’s “New” isn’t as much a review as the current New Yorker‘s position-paper on classic rock (boring, played out, un-hip, irrelevant to where Music Is Now), this review was the stance The Times wanted—perhaps had to take—towards the counterculture, circa 1969. The counterculture was too big for something like The Times to ignore, and still straightfacedly call itself “All the news that’s fit to print”—yet still too new and threatening to see clearly.

…But you know, as off-base as Cohn was, at the very end he shows more perception than he realized: “Really, the medley should have carried on throughout the whole album,” he writes, “and that might have been something marvelous.” Correct me if I’m wrong, commentariat, but wasn’t that what Paul and George Martin wanted to do? Ironically it was John Lennon—the group’s Nik Cohn, beginning a misguided trip-down-memory-lane that dulled his creative edge for the rest of his career—who put the kibosh on that plan. Which I agree could’ve been a fascinating experiment and one ultimately more innovative than Abbey Road became, as splendid as it is.

Thank you, Ed—what an interesting read!

Very interesting. And baffling. I can’t wrap my head around Cohn’s piece. He sounds like an amateur and the review feels slapdash. No mention of Something or Here Comes the Sun? Also, while dissing the record, it’s funny that he comes down on Come Together and Oh Darling instead of more deserving targets like Maxwell’s Silver Hammer and that interminable and misguided outro of She’s So Heavy, a couple very rare Beatles missteps.

Nik doesn’t recognize Paul’s voice on “Oh! Darling” but instead complains that John’s voice doesn’t sound right on the track. That would be like me writing a review of a Marx brothers film, and criticizing Chico’s harp solo.

Who was it that said “a critic is like a eunuch at a gang bang?”

Mike, you’re way off on Chuck Berry and Phil Spector. Just way off.

Chris, I don’t think there’s a single extraneous note in “She’s So Heavy.”

Sam, if critics are eunuchs, what does that make the fans?

Devin, I think you’re reading something different than what I wrote.

Berry and Spector most certainly did go into the shade after February, 1964, as did a lot of other people (every jazz musician, for example). Furthermore, neither Berry and Spector made any substantial contribution to pop music after 1972. Geniuses have second acts, that’s what makes them geniuses–“My Ding-A-Ling” and Spector’s dalliance with Lennon and Harrison are not major contributions, even to their own catalogs. Berry and Spector may be important parts of the schema Cohn created in the late 60s to explain/define pop music, but by 1969, it’s just indisputable that they were much less important in the world outside Cohn’s head. The map is not the territory, and with the benefit of 50 years of hindsight, we see that Cohn makes that mistake constantly throughout the review.

Post-Beatles, I think it’s absolutely fair to call both Spector and Berry nostalgia acts. Lennon hired Spector on what he’d done at least 10 years before, not some hot new LP. Berry’s late 60s-early 70s resurgence was pure nostalgia–viz “Hail Hail Rock and Roll”–and fits with a larger backward-looking cultural trend you can see in movies and comedy, as well.

To me, “You Can’t Catch Me” isn’t even the highpoint of Berry’s own catalog–“Maybellene,” “Johnny B. Goode,” “Memphis,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” and “Brown-Eyed Handsome Man” are all as good–and calling it a “very great song” sounds like a critic deciding to codify his taste for no good reason. Fifty years of pop music since shows us that it’s an overreach to say that, just like it’s overreaching to think of Phil Spector today as the giant some considered him to be in 1963, or even 1973, and that was the point of my post.

IMHO, both Spector and Berry were essential talents in the early development of rock and roll–but their reputations definitely benefitted greatly from being first. Fifty years on, Cohn’s review of Abbey Road sounds like a person with very strong, very idiosyncratic opinions downgrading the work of authentic geniuses because it doesn’t fit inside his schema. That’s shitty criticism because all it tells us about is Nik Cohn, and frankly, who cares?

Sam, if critics are eunuchs, what does that make the fans?

I would assume the fans are part of the gang bang party, if I understand the quote correctly. The artist and the fans are having fun, and the critic sits off to one side, taking notes.

I’m not sure if I completely agree with the quote. There are some critics I actually enjoy reading. Some of my favorite authors have written criticism. But I disagree with just about everything Nik had to say about Abbey Road. His review reminds me of Rex Reed’s review of Revolver. Just wrong and thick-headed.

I wish I still had a copy of Rex Reed’s review. It was reprinted in one of WFMU’s magazines, but since we moved I can’t remember where I stashed it. If it turns up, I’d love to share it.

Sam, I’d say the fans are voyeurs watching the sex–and getting some of the same visceral, sensual pleasure (albeit a different flavor) that the musician-copulators are experiencing. The point being that criticism is a fundamentally head-bound, distant exercise, secondary somehow to what is being critiqued.

In the right hands, I absolutely don’t agree with that; Devin’s stuff, for example. But I will say that being a critic is a distinct gift, quite rare, and one I don’t have myself. Whenever I write it, comedy criticism is a much less intense pleasure than actually writing comedy–and I can only assume that my readers feel the same way!

I remember starting Cohn’s “Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock” and giving up on it because it was so narrowly shaped by his view of what rock “should” be. It’s fascinating that rock music, which at its best is about freedom of expression and the idea that nothing should be off bounds, can breed this kind of fundamentalist criticism. But of course that says more about human nature in general than rock in particular.

However, I do think the high dudgeon in which old-school rock critics (Christgau, Marsh, et. al.) indulged periodically had a lot to do with needing to set Serious Commentary on Rock Music apart from mere fan talk. This was the big boys’ table, not a lot of screaming girls.

with needing to set Serious Commentary on Rock Music apart from mere fan talk

Yes, but that debatably important crusade shouldn’t excuse their need to control the discourse, which only hurts the artform they love.

To use an example in my own field: I LOVE Seventies comedy. It’s what first attracted me to the form, and I think it’s still the highest point of modern comedy. I don’t just prefer it; in my professional view, it’s demonstrably better (sharper, more wide-ranging, more intellectual, more open, more insightful) than what came before or what’s come after. The craft, talent, and times coalesced in a particularly fortuitous way.

But it’s a fool’s errand to try to convince a reader of that; if you don’t see WHY Richard Pryor is better than, say, Aziz Ansari (and no disrespect to him), I can’t help you. If you don’t see how things like Young Frankenstein and Animal House created the modern movie comedy (for better and worse), my saying that isn’t going to help. And so forth in TV (Monty Python) and print (National Lampoon; Hitchhiker’s Guide) and even radio.

Working out a lot of elaborate theories, and spending innumerable words explaining, defending, and (let’s be honest) bullying is not only useless, it’s also peculiar in its need to control what other people think. The best one can do–the only thing, really–is say, “I love this,” explain why, then leave. The critics you mention strike me as displaying a particularly male kind of obsession–a need by some adolescents to claim a bit of pop-cultural turf and dominate it intellectually, a habit that some retain long after adulthood should’ve evened them out. I don’t think this behavior is very good for either the people who do it, or the art they purport to “love.” So I try, not always successfully, to restrain those tendencies in myself and–as ever–find them especially distasteful in others.

TL;DR–Cohn’s obsessions make him a worse critic, not a better one, and make his genuine insights less persuasive. But it’s no coincidence that his view emerged when it did and was lionized, because it was a view of rock that unhip editors at unhip mainstream media outlets could agree with.

I’m reminded of my friend Dick, an editor at Time/Life for many years. He loved jazz, but even though he grew up within spitting distance of 52nd St during the be-bop era—incredibly exciting, incredibly important, and the stomping ground of genuine geniuses—he preferred dixieland, as did most of his set…many of whom dominated publishing and advertising from the 60s to the 80s. (Dick interviewed The Beatles, by the way.) Mainstream media outlets want a bounded culture working within a narrative that they create and can control, and hire people with similarly bounded tastes. Their business isn’t to reflect reality, but create a sellable version of it, and whether it’s Dick or Ben or Nik Cohn, criticism is a part of that. That doesn’t invalidate it, but it should inform your reading.

Mike, I absolutely agree that “the best one can do–the only thing, really–is say, “I love this,” explain why, then leave.” Hectoring people about why they shouldn’t like X or should prefer Y doesn’t work. Certainly the criticism, professional or amateur, that has enriched my appreciation of music falls into the category you describe: people being honestly enthusiastic about something and wanting to share it. Even when I don’t end up being able to share the enthusiasm, it opens a window for me, metaphorically speaking. There are some critics whose negative reviews I enjoy and find useful (George Starostin’s, for one), and they’re those who make a serious effort to meet each work on its own terms.

And gender matters enormously in the rock critical word (Devin’s recent review of the “Beatles v. Stones” book got at this). “Girliness” — anything that could be perceived as naively enthusiastic — is like kryptonite to the old rock-critical standard bearers. Precisely because loving rock music enough to write about it at length and attempt to make a living that way opened critics to the charge of being just fans, it was important for them to distance themselves from that charge. Thus I find a lot of the Jurassic period of rock criticism pretty unbearable for the load of pretension it carries.

Anyone interested in the complicated underpinnings of taste and critical reception in rock/pop music should read Carl Wilson’s “Celine Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste,” from the 33 1/3 book series. Dion’s not at all to my liking, but Wilson’s managed to write a book that explores the popularity of her music and the critical disdain for it in an illuminating way, and opens that out to look at the whole landscape of criticism. (And he does review the album itself, in a remarkably fair-minded way, IMO.)

…gender matters enormously in the rock critical world. “Girliness” — anything that could be perceived as naively enthusiastic — is like kryptonite to the old rock-critical standard bearers. Precisely because loving rock music enough to write about it at length and attempt to make a living that way opened critics to the charge of being just fans, it was important for them to distance themselves from that charge. Thus I find a lot of the Jurassic period of rock criticism pretty unbearable for the load of pretension it carries.

Which is why I always admired Lillian Roxon’s courage, for making her way in the late ’60s as a rock critic, and breaking through the boys’ club.

Must smart a bit to be Nik Cohn and eventually realise you trashed two of the greatest works in all of rock history, not to mention the irony in all the self-important posturing while accusing the Beatles of being self-important.

Or, as Nancy Carr puts it ably above: “It’s fascinating that rock music, which at its best is about freedom of expression and the idea that nothing should be off bounds, can breed this kind of fundamentalist criticism.”