- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

by Chris Dingman, guest Dullblogger

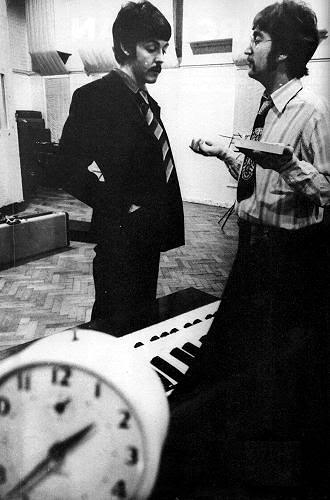

So many stars had to align for the Beatles to come blazing forth. Without a slew of key elements—the end of compulsory National Service in 1960, Hamburg, Brian Epstein, and George Martin, to name just a few—The Beatles as we know them might never have been. Of course the band needed to be those four guys, together resonating far beyond the sum of their parts. But the most essential element in The Beatles’ story was the Lennon-McCartney partnership. It was a connection that could only be forged from the dreams of youth, a marriage that was arguably deeper and more fertile than any conventional one. It was nurtured both by shared sorrow and shared visions of glory.

So many stars had to align for the Beatles to come blazing forth. Without a slew of key elements—the end of compulsory National Service in 1960, Hamburg, Brian Epstein, and George Martin, to name just a few—The Beatles as we know them might never have been. Of course the band needed to be those four guys, together resonating far beyond the sum of their parts. But the most essential element in The Beatles’ story was the Lennon-McCartney partnership. It was a connection that could only be forged from the dreams of youth, a marriage that was arguably deeper and more fertile than any conventional one. It was nurtured both by shared sorrow and shared visions of glory.

As I make my way through my third McCartney biography, Peter Carlin’s, I yet again find fascinating the symbiotic dance that in the early days drew out the powerful collusion of Lennon-McCartney. It may just be that this material on Paul is fresher in my mind, but I find myself leaning towards a view that McCartney provided more than his share of the dynamism that fueled the dynamic duo. Paul, alone of all the Beatles, had everything he needed to be a star—talent, drive, calculation, and charm.

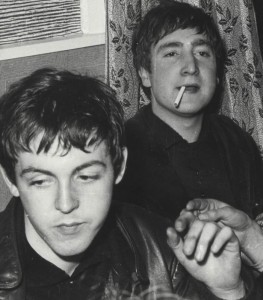

Before Paul joined the Quarrymen, they had been as much a gang as a band. Rock ‘n’ roll had electrified John, to be sure, and he had the raw talent, but he was impatient. He may have loved the idea of being Elvis more than the reality. John’s magnetic personality simply corralled his closest friends, regardless of their talent or even abiding interest, into a reasonable facsimile of a musical group and got them out there flailing about. John was the unquestioned leader. His personality required it. But it’s not as if this leader knew what he was doing. He didn’t have a plan beyond, “I’m John Lennon. Look at me!” He wasn’t exactly scouring Liverpool for the best musical talent. Someone else would have to do that for him.

Before Paul joined the Quarrymen, they had been as much a gang as a band. Rock ‘n’ roll had electrified John, to be sure, and he had the raw talent, but he was impatient. He may have loved the idea of being Elvis more than the reality. John’s magnetic personality simply corralled his closest friends, regardless of their talent or even abiding interest, into a reasonable facsimile of a musical group and got them out there flailing about. John was the unquestioned leader. His personality required it. But it’s not as if this leader knew what he was doing. He didn’t have a plan beyond, “I’m John Lennon. Look at me!” He wasn’t exactly scouring Liverpool for the best musical talent. Someone else would have to do that for him.

John may not have actively pursued assistance, but he always left openings for it. When the right person came along, he let them in through the little chinks in his armor. He instinctively knew he needed a partner, whether Paul, Stu, Cynthia or finally Yoko. Let the Bob Dylans go it alone—John needed help.

John’s invitation and Paul’s confidence

When it came to kicking his band up a level, Lennon’s immediate savior was his pal Ivan Vaughan. Bless that boy’s heart! It’s Ivan we have to thank for introducing Paul and John. (Vaughan’s death from Parkinson’s in 1993 moved Paul to turn to poetry for the first time since he was a boy. The poem “Ivan” appears in Paul’s book Blackbird Singing.) Vaughan took it upon himself to tell Paul about John and suggested they meet. John was wary at first, that day “backstage” at the Woolton fete. And even after Paul’s bravura performance of “Twenty Flight Rock,” John wasn’t sure about letting him in. He could be a threat.

John had the swagger and the snarl, but his glimpses of his own genius flickered wildly. Paul’s confidence was steady, foundational. (It never seems to have wavered over the Beatle years.) When Paul auditioned for John’s band it was not only his skill but his assurance that impressed the boys. Paul knew he was good. Without the steady blaze of Paul—like a home hearth for his partner—John would have died in the cold.

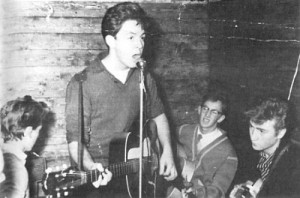

After Vaughan’s introduction, Paul was John’s newest—and greatest—savior. Things started changing. Paul brought professionalism and a kind of discipline to the band. He became the de facto musical director, showing John how to properly play guitar (John was using a banjo tuning), providing harmonies, and even showing drummer Colin Hanton what rhythms to play (thus speeding Hanton’s departure from the band). It was Paul who got George Harrison into the band too. Paul recognized George’s talent, but John at first rejected the guitarist as too young to look cool in a rock band. Paul had to gently persist. He made sure musical considerations trumped superficial ones. Paul would of course go on to make a good claim as the best bass player in rock. In The Beatles, he was also the best piano player and maybe even technically the best lead guitarist and drummer. He also had a heavenly sense of harmony and led the Beatles charge into musical experimentation. Paul just was music.

After Vaughan’s introduction, Paul was John’s newest—and greatest—savior. Things started changing. Paul brought professionalism and a kind of discipline to the band. He became the de facto musical director, showing John how to properly play guitar (John was using a banjo tuning), providing harmonies, and even showing drummer Colin Hanton what rhythms to play (thus speeding Hanton’s departure from the band). It was Paul who got George Harrison into the band too. Paul recognized George’s talent, but John at first rejected the guitarist as too young to look cool in a rock band. Paul had to gently persist. He made sure musical considerations trumped superficial ones. Paul would of course go on to make a good claim as the best bass player in rock. In The Beatles, he was also the best piano player and maybe even technically the best lead guitarist and drummer. He also had a heavenly sense of harmony and led the Beatles charge into musical experimentation. Paul just was music.

It’s to John’s credit that he could allow his ego to step back where musical matters were concerned and allow Paul to call the shots. And if John occasionally needed to metaphorically slap Paul around, well, Paul could accept that as part of the package. There was an unspoken understanding of how the ship would be co-captained. John’s role was more passive. He may have drunkenly shouted orders every now and then, but as long as everyone pretended to listen, they could all sleep it off and do things Paul’s way in the cold light of morning. We can imagine, for example, John making the obligatory snide remarks about wearing matching suits, and the other three snickering along, even as they were all being measured for a perfect fit.

Paul’s genius wasn’t the temper-tantrum-prone, self-destructive, moody type—making it all the more remarkable. It was matched with the charm of a diplomat. According to Carlin, Paul possessed this skill from his earliest years. As a schoolboy, he served as a sort of unofficial liaison between students and teachers, effortlessly keeping an irreverent foot among his peers and a respectful one among the faculty, never losing credibility with either group. He served the same function for The Beatles, softening their rough edges for the establishment, cannily flashing his cherubic smile, somehow managing to be both cheeky and polite, often simultaneously.

Paul’s genius wasn’t the temper-tantrum-prone, self-destructive, moody type—making it all the more remarkable. It was matched with the charm of a diplomat. According to Carlin, Paul possessed this skill from his earliest years. As a schoolboy, he served as a sort of unofficial liaison between students and teachers, effortlessly keeping an irreverent foot among his peers and a respectful one among the faculty, never losing credibility with either group. He served the same function for The Beatles, softening their rough edges for the establishment, cannily flashing his cherubic smile, somehow managing to be both cheeky and polite, often simultaneously.

Paul and John as each other’s alarm clocks

For all Paul’s reputation as the softy crafter of lovey-dovey pop ballads, he was in his own way as steely as John. They both had shells around them. John’s was just more dramatic and spiky. John could beat the shit out of someone but also open up like a child—all unruly impulse. Many have noted, though, that Paul’s shell was deployed craftily—and rarely came down. He could be the life of the party, earnestly asking after your welfare, oozing warmth and wit, but there was a way you were kept separate at the same time—some inner space you only got to if you were John, maybe, or Linda. There seems to have been more than a little of Machiavelli in Paul. We are told that at their first meeting with Brian Epstein, Paul arrived late on purpose, as a way to demonstrate power—and then pulled Epstein aside to inform his new manager that the band was all well and good but that no matter what, he, Paul McCartney, was going to be a star. (I don’t think that story, if true, necessarily means Paul didn’t care about his friends.)

John of course wanted to be a star too. He wanted to make it. But part of him also couldn’t be bothered. His genius and ambition were mixed with equal parts laziness and pride. The knocks John’s artistic soul had taken (unfit parents, the death of a father figure, then the death of his mother) left him right on the edge between self-destruction and success. The great blow of Paul’s early life, the loss of his own mother, may also have been the cause of his shell. But even in the early days, Paul put that steel to good use. He started playing the guitar—all the time, obsessively. And after glimpsing the promise of his partnership with John, he relentlessly pursued it. When John withdrew in the months following his mother’s death, it was Paul who kept at him, tactfully yet persistently refusing to let the music—his vision—die. Later, when John again backed away from the band in favor of art school and his new friend Stu Sutcliffe, Paul kept showing up, guitar in hand. He wasn’t letting this fellow-genius go. It was as if John would occasionally fall asleep, not care, and Paul would be there by the side of the bed, shaking his shoulder, “John! Wake up! Wake up!”

John of course wanted to be a star too. He wanted to make it. But part of him also couldn’t be bothered. His genius and ambition were mixed with equal parts laziness and pride. The knocks John’s artistic soul had taken (unfit parents, the death of a father figure, then the death of his mother) left him right on the edge between self-destruction and success. The great blow of Paul’s early life, the loss of his own mother, may also have been the cause of his shell. But even in the early days, Paul put that steel to good use. He started playing the guitar—all the time, obsessively. And after glimpsing the promise of his partnership with John, he relentlessly pursued it. When John withdrew in the months following his mother’s death, it was Paul who kept at him, tactfully yet persistently refusing to let the music—his vision—die. Later, when John again backed away from the band in favor of art school and his new friend Stu Sutcliffe, Paul kept showing up, guitar in hand. He wasn’t letting this fellow-genius go. It was as if John would occasionally fall asleep, not care, and Paul would be there by the side of the bed, shaking his shoulder, “John! Wake up! Wake up!”

But it’s not that simple. And this is why the partnership is so beautiful. John had woken Paul up too. Twice, actually. John’s role for Paul was not as the steady warmth of a hearth, but as a bolt of lightning that zapped him at just the right moments.

For even though Paul’s mum had died, even though Paul was obsessed with playing guitar, even though Paul had entertained scores of kids at summer camp and even thereby gained some female admirers—even though, in other words, Paul had all the makings of a driven, brilliant musician—he wasn’t headed in that direction before he met John. Paul wasn’t even thinking about forming a band it seems when Ivan invited him to meet John. He might have, had John not come along—who knows. But I think in most parallel universes in which Paul never met John, McCartney goes on to become a teacher. I don’t think there’s anything eccentric enough in his environment to knock him out of the default, work-a-day path most people around him were on. I don’t think there was anything that reflected back at Paul a vision of what he could be. Except for John.

The second time John woke Paul up was after they returned from their first trip to Hamburg. They’d been booted out, actually. They had defected to a rival club, goading their jealous ex-boss to tell the authorities that George was too young to be working (true) and moreover that John and Paul had tried to burn his bar down (false). The band trailed home haphazardly and went their separate ways. George even joined another band. Paul, at his father’s urging, got a job. It was some boring job but, being bright, Paul began working his way up in it. According to biographer Carlin, Paul was ready to accept this as his lot. His “bourgeois” upbringing (an insult that has dogged Paul throughout his career) had overcome his ambition. Until John showed up on the job site one day and said something to the effect of, “What the hell are you doing, mate? Let’s get the band back together. Let’s rock ‘n’ roll!” Paul jumped the fence and never looked back.

The second time John woke Paul up was after they returned from their first trip to Hamburg. They’d been booted out, actually. They had defected to a rival club, goading their jealous ex-boss to tell the authorities that George was too young to be working (true) and moreover that John and Paul had tried to burn his bar down (false). The band trailed home haphazardly and went their separate ways. George even joined another band. Paul, at his father’s urging, got a job. It was some boring job but, being bright, Paul began working his way up in it. According to biographer Carlin, Paul was ready to accept this as his lot. His “bourgeois” upbringing (an insult that has dogged Paul throughout his career) had overcome his ambition. Until John showed up on the job site one day and said something to the effect of, “What the hell are you doing, mate? Let’s get the band back together. Let’s rock ‘n’ roll!” Paul jumped the fence and never looked back.

Chris has written comedy, screenplays, comedy screenplays, poetry and pop songs. He blogs at nosuchthingasastraightline.wordpress.com, and has released three Crooked Roads CDs. You can listen free to his latest music here.

Me first huh? Well as I have said on Youtube, as talented (and brilliant) as Lennon was, there was no way that he was ever going to make it to Hamburg, or even out of Liverpool, let alone the world stage, some sort of Elvis/musician wannabe with his group of musically untalented, skiffle playing friends. John did not have the discipline, focus, drive for that.When Paul McCartney came along and joined John’s band, greatly influence John, and with John’s okay, began to instill discipline into their practice sessions, (rehearse before play, drink, party, “this is serious!”), one by one the band started to lose the dead weight, add raw talent “too young” George, drop skiffle, play rock n roll. Keep John focus on the prize, “Toppermost of the Poppermost!” Without McCartney, maybe just maybe, Lennon might would have become some sort of writer. But he would have needed focus, drive, ambition…so maybe not. I always thought that IF there was never a such thing as The Beatles, and IF any of them were to have ever made it as a solo star, I think it would have possibly been Paul, then Ringo. I’m talking really big IFs. IMHO.

Water Falls, we’re doing that crazy Dullblog thing where one of us starts writing a comment on a post and it turns into a post of its own, so Mike’s recent post is kind of gathering up comments on both.

Great post Chris. It think you captured what an enormous contribution Paul made to the group’s success. Leadership takes many forms; in addition to the great talent they each possessed, John’s leadership was based on the sheer drive of his social power, while Paul’s leadership was based on the ability to operationalize the vision. It was the perfect blend.

Thanks, @Karen! I agree they were both needed, but John was too lazy, self-destructive and unfocused to go anywhere on his own. Paul would have gone somewhere without John, just not to the toppermost of the poppermost.

You’re welcome. 🙂

…And that’s such an important part of the narrative, I think. By his own admission, John probably would have squandered his enormous talent and ended up in jail, or worse. He always boasted that he had the foresight to choose Paul as a partner, but I wonder if he realized just how much he owed him.

@Karen, I think knowing how much he owed Paul was the seed of John’s rage. The moment Yoko comes on the scene, John’s whole world becomes showing he doesn’t need, is better than, and would’ve been successful without, Paul. This is utterly foolish, which is why John had to work so hard putting it across.

I wouldn’t be surprised if, when things were breaking up, Paul actually reminded John of just how he’d been carrying him since Brian died. That would make John walk.

Good point, MG.

Paul and John needed each other, absolutely. You don’t have The Beatles without both. They catalyzed, collaborated, and competed with one another. John was brilliant, funny, quirky, and the central personality of the early Beatles. He was the leader of the band because of that personality and its heat. He was not the leader because of any vision or drive. He was fundamentally lazy. He only began writing songs, for example, at Paul’s urging. Once Paul got him going, he could see he had a gift and kept doing it, either on his own or with Paul. But he was most productive during the days of non-stop touring which provided a kind of structure for his life. He could write songs in the hotel room or on the bus—what else was he going to do after his other appetites had been satiated? If he walked outside, he’d be torn to pieces. After they stopped touring, his productivity fell off. At his suburban mansion, he drifted into a drugged-out haze, occasionally turning out masterpieces. It was up to Paul to keep him interested in songwriting or even The Beatles at all after the touring stopped. Paul was the one who drove out to the mansion to write with John. Paul kept his finger on the heartbeat of swinging London. Again, because John couldn’t be bothered; he did not have vision or drive—just undisciplined brilliance that needed others to hone and channel it. John needed George Martin and Paul to nurture and mold his songs into their fullness. On his own, he was lost.

Assuming that the post-Epstein state of affairs was always how the Beatles worked is not supported by the facts.

As this thread on SteveHoffman.tv reminds us, the work ethic of the early Beatles was nothing less than astounding. John Lennon could not have participated in this, much less led or co-led it, if he were fundamentally lazy. He can’t simultaneously be “the central personality of the early Beatles” and a layabout. Look at the Lennon-dominated lineup of “A Hard Day’s Night” — does this seem like the work of a guy who couldn’t be bothered?

Post-drugs, and post-Yoko, John’s pretty lazy. But John in 1960-66? Not lazy. The guy worked his ass off, as they all did. He had to.

What I’m trying to do in this thread is help us see BOTH guys more clearly. It doesn’t do any good to substitute the “John’s the genius” myth with a “John was a schlub who needed Paul to get him off the couch” one. In ’68? Sure — but in 1960-66? Just not so.

The contention here, though, is that the hard-working, ultra-productive John of the 62-66 period was a function of the supportive systems that were in place to make that happen–touring, Paul, George Martin, etc. Without them, would John have been so productive, alone in his room at Mimi’s?

Would he have been writing songs? Probably not. Would he have been writing poems and stories and plays and doing other things you don’t need a support team for? Very probably — because that’s what he was doing before the Beatles. Whereas Paul was planning to be a teacher.

Look, I admire Paul immensely. And nobody on the entire internet is more willing to examine John’s faults, in exhaustive detail. But young John should be given credit for who he was, just as older John should be somewhat mourned for who he became. Young Paul was much more cautious and circumspect, and that caution and circumspection may well have kept solo Paul from being more than a weekend musician like his father. Even as late as 1961, John had to kick Paul in the ass not to give up his dream of playing music professionally. That’s something a leader does, not a magic doodler.

This, I think, is a fairer way of looking at young John and Paul; young John wanted to be an artist of some sort, and his brain chemistry gave him drive and ideas to burn…for a time. John kindled Paul, whose brain chemistry made him start slower, catch up, and eventually surpass his partner. To suggest that Paul was Lennon’s equal before 1966 or so is, to me, Wennerism in reverse.

To add another layer to this, Paul’s primal form of artistic expression was and always has been, music, whereas John was more of a jack-of-all-trades who chose music over other forms of artistic expression. So where Paul was writing music and lyrics months before he met John, and John was writing poems months before he met Paul, both of them had already begun expressing themselves artistically prior to their introduction. Personally, I don’t see John as the catalyst for spurring Paul’s artistry — I believe his mother’s death and his own innate musical abilities did that — but rather as fanning the flames of something that had already ignited. Without John fanning those flames, perhaps Paul would have settled for a weekend-musician, but the desire to express them pre-dated John.

I also think its a bit simplistic to regard John’s ultimatum to Paul regarding the job at Massey and Coggins or the band as a demonstration of John’s leadership, or at least good leadership. The ultimate outcome benefited both John and Paul, (not to mention us fans) but suppose Paul had called John’s bluff? Decided he liked the idea of a steady job, moving up to management, and becoming a weekend musician like his dad? Writers like Philip Norman like to use this scenario to demonstrate just how much authority John had over Paul at this point in time, but no one seems to acknowledge the inverse; if Paul had chosen Massey and Coggins, and his dad, over John, and John had booted Paul out of the band, we probably never would have heard of Paul McCartney — but you can be damn sure we never would have heard of John Lennon and the Beatles, either.

Perhaps John issued the ultimatum with absolute certainty that Paul was going to choose the band, but if not, he’s certainly risking the band’s future (as well as his own) … why? Because he’s tired of Paul being late for a few Cavern lunch sessions? Not to mention how John twisted the whole scenario into a “Me or Jim” Sophie’s choice psychodrama, and ignored the reality of Paul’s working class situation (Paul needed the money) as opposed to his own, far more comfortable middle-class one. That doesn’t strike me as good leadership; that strikes me as impatience, insecurity and psychological issues teaming up to make John willing to cut off his nose to spite his face — something he will do later on, in 1968 and later.

Personally, I think everyone here has done an excellent job of examining the nuances of the situation, but “equals” might be a term that defeats us, because of how subjective it can appear to different people. I do find it interesting that, in the introduction to “Tune In,” Lewisohn labels John and Paul as “equals,” and doesn’t specify the time period he regards them as such, whether it is for the duration of “Tune In’s” time period, up to the end of 1962, or the whole of the Lennon/McCartney partnership. Having read “Tune In,” it is clear that Lewisohn demonstrates that John was the dominant personality and charismatic leader — as well as the Beatle all the others wanted to be closer to; the big guy in the chip shop. But Lewisohn also shows us how Paul’s superior musical skill elevated him above John in that regard and, however crucial John’s image was the Beatles were also a musical band. Paul wasn’t John’s equal in terms of hierarchy, whereas John wasn’t Paul’s musical equal. Both knew it, and implicitly accepted it, albeit with a few bumps in the road … but by 1967, Paul is widely viewed as the de-facto leader as well as the musical dominant, that decade long understanding they had collapsed.

@Ruth, cogent as always. I absolutely agree that Paul’s musical talent and interest pre-dated John Lennon; but for all the talk in the thread about Paul focusing John, the chronology suggests that the same could be said in reverse. Which is an interesting thought?

“but you can be damn sure we never would have heard of John Lennon and the Beatles, either.”

That seems rather harsh. Why do you have little faith in John Lennon, age 21? To me, the Lennon of that era seems utterly determined to become famous, and as we found out, he was plenty talented enough to do it. If you’re saying he wouldn’t have picked music, or changed the world, I’d agree with that. But to my eye — and I’ve worked with a LOT of talented writers and artists of that age — Lennon very likely would’ve made a reasonable-sized mark in writing and illustration. If he’d avoided the drink. It was well within his reach to become a Ralph Steadman, or perhaps even a Terry Gilliam-like illustrator-turned-filmmaker.

As a leader of creative teams for most of my life, I can tell you: good leadership is what moves the project forward — what gets the necessary result. In that instance, bullying worked with Paul; but it wouldn’t always work, and what worked with Paul was not what worked with George or Pete or Ringo. Post-Yoko, Lennon was a terrible leader, so bad I happen to think he was actively sabotaging the group. But in the early days? He got it done, and we have to give him that, especially because it’s not an accomplishment that can be found on a tape log.

“Why do you have little faith in John Lennon, age 21?”

—

Because before meeting Paul, John made little or no effort to pick people who would make his band better. John just formed a band from his friends and underlings, whether they had much musical talent or interest in music as a career or not. It was Paul’s arrival that spurred the band to become an actual BAND with people who not only had talent musically but commitment to the idea of being a band.

That seems to be a pretty high standard to hold any 17-year-old to. When he met Paul, he asked him to join the band; and he kept them in the band, no matter what. Conjecturing other musicians of his age in Liverpool who might’ve theoretically made the band better, and then finding John wanting for not making them Beatles as well… Doesn’t seem fair to me. Seems like you’re looking at John Lennon at 28 and giving him the same flaws at 17–as if nothing happened in the interim!

But I think, MG, that this is missing an essential point when we talk about the development of the Lennon/McCartney creative partnership.

It’s not really unfair to hold a 17 year old to that standard, because we can hold Paul to it quite easily, at an even younger age. Paul didn’t suggest George to John as a possible addition to the band because he was a mate, he suggested George because George could play the guitar. If one acknowledges Paul’s early contributions in this regard, which I think we should, the comparison to John is fair game.

But the beauty of this is that it’s not a criticism of John, because John chose Paul to make the band stronger. It’s the beginning of the helix, the first connections which laid the groundwork for their future partnership.

That’s an interesting point, Ksren, but it also illustrates where and how I feel this conversation keeps going off the rails.

Someone says that Lennon wasn’t a good leader because he wasn’t turning over every rock in Merseyside to find the best players — an opinion loaded with assumptions: that the best players make the best music; that finding and wooing said people would be possible; that a band so constructed would be better. Nobody who’s put together and managed a team of artists would say any of this; it’s not how good creative teams are constructed, nor how the best art is made. But whatever, we go off and chase that hare for a few comments.

Meanwhile the fact — that John grabbed Paul and did everything he could from 1957 to keep the guy happy and in the band (probably not easy, I can tell you from working with talented young artists), this fact is submerged in a bulldog-like determination to assign certain characteristics to John (lazy! Unfocused! Mentally unstable!) and others to Paul (workaholic! Professional! The true musician of the group!), behavior or facts to the contrary be damned.

Nobody’s arguing that these characteristics weren’t roughly accurate in the years we have a profusion of data for. But a lot of things suggest that the early years functioned differently, and I simply don’t get the resistance.

I mean, my gosh — when I have to actually defend the idea that John Lennon was the acknowledged leader of the early Beatles — there’s some distortion going on here. At best some simplifying.

The standard narrative is John formed the group, and John led the group, with Paul as his willing second-in-command, until the end of touring, when a combination of Lennon’s drug use, and Paul”s greater interest in and proficiency for, studio work, combined with the death of Brian Epstein, broke this stable arrangement. This has been confirmed by all parties, and fits snugly with what we in the public know as well. Any new narrative that diverges from this will require a lot of very persuasive evidence, and nobody’s providing it. George Martin saying that they were both geniuses? Of course they were both geniuses; but who’s applying basic technique to that source? In addition to Johns well-publicized insults, George Martin was always more simpatico with Paul, and even worked with him post-Beatles! (He was, in fact, working with him in the early 80s around the time Norman interviewed him.) George Martin is hardly an unbiased source when it comes to Paul, especially in the post-1980 period when Lennon’s reputation was inflated (and thus Martin’s was depressed).

These threads have been almost entirely based on the public personae of John and Paul — how each seems to be — which is why I keep wading in. If you want to believe John Lennon was “lazy” in the pre-pepper period, I can only point to the amount he produced. Likewise if you want to believe that Paul was always the grown-up studio musician professional, I can only remind you that he apparently stormed out of the Revolver sessions.

These guys changed, and grew, and their relationship was complex. And you better believe they acted differently with each other, behind closed doors, than what they showed the public. It’s always better to use what they did, not what they said later, as the key. I’d like to see more of that in this thread.

Just want to second this, Mike. I don’t think there’s any question that, early on, John was the one who inspired Paul to take the major risk of committing himself to the band and taking off for Hamburg. John had to pull Paul out of orbit, and Paul’s pretty well acknowledged that in interviews. If Paul hadn’t had the same basic ambitions that John did, he wouldn’t have responded to John’s invitation; but it was John’s desperation and force of personality that made the invitation so tempting. He was the one with the initial vision, and he deserves the credit for that.

Paul’s role in the band has been undervalued by many, but I agree that we shouldn’t swing so far the other way that we start undervaluing John’s role.

“Any new narrative that diverges from this will require a lot of very persuasive evidence, and nobody’s providing it. George Martin saying that they were both geniuses? Of course they were both geniuses; but who’s applying basic technique to that source?”

Someone has; it just won’t be published till Summer. You can take a sneak peak in Chapter Two, under “The Credibility of George Martin,” if you want to. 🙂 It largely agrees with many of the same arguments you made in your post, with some additional information.

I agree with your overall point that John was the leader, and exerted the height of his power pre-fame and, pointedly, pre-studio. But George Martin’s assessment of John and Paul as equal geniuses can co-exist with the acknowledgement of John’s preeminent place in the Beatles hierarchy, both pre-fame and until 1966. Using Martin’s assessments regarding John and Paul’s equality and necessity to the Beatles doesn’t contradict the accepted narrative that John was the leader in the early years, even though you could make a convincing case that Martin’s testimony favors Paul if, for no other reason, than Martin’s preference for Paul’s musicality. Of course, on balance, you could make the same argument that, due to his preference, Brian’s contemporaneous comments and actions might tilt favorably towards John.

“It’s always better to use what they did, not what they said later, as the key.”

On this, I wholeheartedly agree. Contemporaneous sources always outrank retrospective ones.

I am attempting to understand the Lennon-McCartney creative partnership using concepts of transactional leadership and by borrowing (shamelessly) from Shenk’s hypotheses about the nature and development of creative pairs. There is no inherent judgement in this, and it allows us, in my view, to go beyond the standard narrative and “public personae” of John and Paul.

I’m not challenging the idea that John was the early leader of the Beatles; I’m challenging the view that Paul was a wide-eyed, hero-worshipping sycophant whose only contribution in those early days was to show John how to play some chords. I believe, and the data shows, that Paul assumed a leadership role which complimented John’s and was, in my view at least, just as vital in the formation of their creative partnership. In order to talk about this, it’s necessary to pull the threads apart and see if we can’t re-weave them into a more accurate narrative.

To understand, for example, that John constructed a band based on friendship rather than talent is important because it enables us to see Paul’s contribution and (leadership) clearly. Similarly, to understand the precise nature of John’s leadership style is to understand the importance of charisma and motivation in the development of leaderful behaviour.

I can’t speak for everyone, but I think that the comments in this thread are an attempt to reconstruct the weave to more clearly identify the contributions Paul made to the Beatles’ early development. This necessarily involves dissecting John’s leadership behaviour, but with an objective eye and without judgement. I see this as advancing, rather than derailing, the conversation.

I’m challenging the view that Paul was a wide-eyed, hero-worshipping sycophant whose only contribution in those early days was to show John how to play some chords.

…and I’m impatient with that, because nobody believes that here. You’re arguing for something already long past proved: that Paul McCartney was also a genius, essential to the success of the Beatles, who helped the music and chemistry of the band in innumerable ways. What I’m arguing is that John Lennon changed, as a person and a Beatle, and that change is absolutely foundational to making any sense of the guy. And if one believes that he was less than the leader of the Beatles in the early years, one is lessening the fact of that deterioration — essentially pulling a Goldman, which isn’t any more accurate or helpful than believing the “Lennon Remembers” view of Paul.

I’d add that Paul looking up to John doesn’t equal his being a sycophant. He could stand up to John when he needed to and could work around him when he had to. But that he did genuinely look up to John seems clear to me. I see that as a strength of his, not a weakness.

“…and I’m impatient with that, because nobody believes that here. You’re arguing for something already long past proved: that Paul McCartney was also a genius.”

And I never said that people believe that here; I’m talking about public assumptions. And my discussion about Paul’s leadership has zero to do with trying to convince you or anyone else about Paul’s genius.

I don’t know how else to make myself clear so I best just leave this discussion.

Karen, I appreciate your emphasis on leadership styles in this thread; it’s given me a lot to think about re: Lennon and McCartney. In addition to differences of style, I think we’re also trying to unravel differences between perceived power and behind-the-scenes power. Very complicated, especially since the balance also changes over time.

In the broadest terms, Lennon as inspiring motivator and.McCartney as pragmatic actualizer make most sense to me. The band badly needed them both.

In the broadest terms, Lennon as inspiring motivator and.McCartney as pragmatic actualizer make most sense to me. The band badly needed them both.

Thanks Nancy–that’s the essence of what I was suggesting.

And it only took me 10 comments to get it! 🙂

Ha–we are a tenacious bunch here at HD! 🙂

Because sometimes thinking too much WORKS!

Aw, don’t Karen. What you’re saying is much more interesting than what I’m saying. I’ll be the one who leaves everybody alone. 🙂

Ok. I had a beer and I’m back in my happy place. (Got one for you as well, MG. 🙂 )

It’s hard to fine-tune our understanding of the Lennon/McCartney partnership because we have 50 years of, as Ruth so aptly termed, ‘orthodoxy’ to slog through. If we want to do a good job, I think this requires us to re-examine old information in a new way. And if we follow the empirical data, I think we can only do justice to the Lennon/McCartney legacy.

(Got one for you as well, MG. 🙂 )

Beer? I remember beer fondly. Surveying my life, I note that my vices have shrunken to a pitiful few. But those I can indulge in, I attempt with great verve. 🙂

“I’m challenging the view that Paul was a wide-eyed, hero-worshipping sycophant whose only contribution in those early days was to show John how to play some chords.”

He was pretty, too; Karen. 🙂 Both Jonathan Cott and Philip Norman argue that one of Paul’s major contributions to the band, both before and after fame, were his looks.

Ha–so true. I should have said pretty hero-worshipping sycophant. And contrary to what the biographers wish us to believe, it seems that it was Pete Best rather than Paul who was considered eye candy back in the day (“mean, moody, and significant”, I think was the phrase). It was even suggested (by biographers, of course) that Best was sacked because the others were jealous of all the female attention he was getting.

wasnt it ‘mean, moody, and magnificent ‘? 🙂

Damn auto correct anyway. 🙂

I’d argue that both of them focused each other; particularly in the beginning. It must have been almost like a lightening bolt, when they realized what they had found in the other one; how often do you stumble across a fellow genius at a churchyard fete?

Where the issue gets sticky would be matters of proportion, which are impossible to determine. I find Pau’s instinctive musical bent as opposed to John’s more generally artistic bent crucial; both Stu and Yoko appealed to John for a variety of reasons, including offering non-musical ways of artistic expression. John loved rock and roll and the rock and roll image, but it did not become his primary form of artistic expression until he met Paul. it’s partially because of Paul, and the Lennon/McCartney partnership that music continues to be his primary method, until Yoko, when he delves further into other areas; perhaps part of her appeal was their ability to experiment in areas beyond music.

My harshness was directed more at Philip Norman, and others who, as I mentioned, present one side of John’s ultimatum without considering the potential consequences — writers who use it to illustrate John’s dominance, but fail to note how, if it had backfired, and Paul had called John’s bluff, they probably wouldn’t have been writing a biography of John Lennon in the first place.

Your take on John’s potential, minus Paul, is simply more optimistic than mine, given John’s psychological issues and addictive issues. Didn’t John himself argue that without the Beatles, he probably would have turned out like his father?

“good leadership is what moves the project forward — what gets the necessary result.”

Even at the risk of blowing the whole edifice up? I’d argue that the intentions of the leader are important as well, and a cost-benefit analysis. If John’s obsessive driving goal was to get to the toppermost of the poppermost, — if that was what all his leadership was intended to achieve — than issuing Paul (whom he unquestioningly needed get to the top) a “do it my way or get out” ultimatum over Paul’s occasional tardiness to a couple Cavern lunch sessions is killing a fly with a hammer and potentially breaking the table underneath. John’s bullying leadership in this instance could have destroyed everything John wanted to achieve; IMO, the downside outweighs the desired result so overwhelmingly the risk was simply not worth it, and the leadership demonstrated was poor. There are nuances, of course, but given John’s psychological issues, particularly regarding Paul’s relationship with Jim, how much of John’s ultimatum was due to his genuine desire to reach the top, and how much was prompted by his own insecurity, jealousy, and impatience?

Ruth, my optimism regarding the young Lennon comes from my experience working with many bright and talented artists of that age. I’m a pretty good judge of 21-year-old horseflesh. But of course it’s just conjecture.

Regarding the ultimatum: John Lennon was there, I wasn’t. It was his band, not mine. He knew Paul McCartney in 1961, I didn’t. All we can say for sure is, the gambit worked, brilliantly. Paul was cemented to the Beatles forever. If it’s not how you would’ve done it, or I would’ve done it, it doesn’t really matter, and criticizing its style seems to be looking for demerits, to no great purpose. But that’s of course what we do here. 🙂

One other thing that can’t be underestimated. While Paul had the musicality, the professionalism, the drive to make the band about more than just a vehicle for John to hang out with friends, I do think Paul absolutely needed John for 2 key reasons: (1) John was cool from the beginning; Paul wasn’t. (2) Paul needed John’s arrogance. Paul was confident and competitive and driven but easily crushed by a bad performance or by criticism. John wasn’t. John was convinced, as Ray Davies once said, that “everyone else was shit.” I think John’s arrogance helped push Paul past his failures/insecurities while Paul’s perfectionism and ambition helped push John past settling for mediocre musicianship.

—

I’m not sure either would have made it out of Liverpool without the other.

Maybe so, Drew. That makes sense. But you know, in 1964 John Lennon wasn’t arrogant–he was fucking right. Everybody else was shit, compared to his band.He could see what other people could not see, and that is a form of genius.

“He was fucking right.”

—

Actually he wasn’t. He was lucky and there were any number of moments when things could have gone the other way.

—

He was one member of one band, among dozens of bands in Liverpool at the time. If Lewisohn’s book showed us anything, it was how much the Beatles’ early success was just dumb luck. Not fate. Not even talent. It could have gone the other way for them any number of times and the individual Beatles themselves actually gave up (each of them, except George) at different times.

—

John’s arrogance in 1960 and 61 was based on pure ego — and not on any foresight or discernible genius of the band at that moment in time. In fact, lots of folks thought the Beatles were shit then, and on the weak side of the various bands then playing in Liverpool. A whole lot of serendipity happened to get them to Brian’s attention and then to get them to EMI’s attention. It wasn’t ordained. And it wasn’t because “everyone else was shit.” Their success was a complicated mix of ambition, drive, arrogance, and plain old luck.

@Drew, here’s what I said:

“in 1964 John Lennon wasn’t arrogant–he was fucking right. Everybody else was shit, compared to his band.”

Lennon’s irrational excessive self-belief — which is a necessary trait if you’re looking to change the world — was proved correct in 1964. If we’re going to slam him for being irascible, impolitic, immature, unpleasant (all things we do around here ad nauseam), we also have to recognize that his self-belief proved accurate to a degree unmatched in the history of popular music. Dismissing it as arrogance or mania pathologizes Lennon’s genius.

And while we praise Paul’s gifts (which we also do ad nauseam), we also should acknowledge that he did not have John’s irrational excessive self-belief, which was necessary for the Beatles to happen, and happen as big.

Paul’s a natural second banana; he’s said as much himself. He’s Woz to Lennon’s Jobs. No shame in this, it’s just how the guy is wired, but it meant that he needed a boss for a decade, before he fully came into his talent. Sometimes that boss was Lennon; other times, Brian; other times, George Martin. But ignoring this part of how Paul works, simply because Lennon was a jerk often admired by jerks, or because we find people like Paul more admirable — it doesn’t help us understand anything.

Michael: I haven’t been slamming John. All I’ve been arguing is that the leadership of the band was shared from 62 on. It’s you who insist on portraying John as the sole leader until 66, and ignoring or dismissing evidence to the contrary.

—

You’ve turned Paul into a caricature every bit as limiting and unhelpful as the one you’re accusing people here (I’m not sure who) of turning John into.

—

Paul loved having a partner. He didn’t love having a boss. In fact, it’s pretty well documented that Paul hated bosses. And in his own way he resisted the boss at every turn — from his Dad, to John, to Brian Epstein, and even George Martin. Paul has a long history of resisting what people told him to do and going his own way. I can think of countless examples.

—

In fact, both John and Paul were massively confident and massively insecure. It’s just that their great confidence was in different realms, as was their insecurity. Whatever Paul said about being comfortable as playing second in command, the reality was: (1) He wanted to be front and center every bit as much as John did and (2) Paul was leading the band in many ways behind the scenes. That doesn’t take anything away from John’s leadership; I’m talking about two different forms of leadership and both were essential to the mix.

Drew, I’m sorry if you feel I’ve been caricaturing Paul. This is not my intention.

It is been my experience that in every creative partnership, and I have been in many of them personally, there is a leader and a follower. Each are essential; and these labels are not absolute–they don’t apply in every situation. But they do hold true in a general sense.

In this conversation, people misunderstand the label “follower” to mean lesser than, or subservient to. It is not. The reality is much more complicated than that, much more fluid; and the complex interplay can’t really be known by people outside the partnership.

There are two people who knew how John and Paul worked together, really, and one of them is dead. And both of them have massive egos. The best we can do is guess, sympathetically, and my sympathetic guess is that John ran the show in the early years. Your mileage may vary.

Please don’t hit me if I again quote Shenk, but–power is not absolute. Each member in a creative pair must be able to lead AND follow.

John and Paul could do both, in turn, and to their great credit.

Karen, I’m wondering if you should interview Shenk. If we could get that to happen I think it would be amazing.

Wow. That WOULD be amazing! What an opportunity.

I’ll work on that. Start assembling questions.

You can’t see this, but I’m doing a wild happy dance. 🙂

Of course, Karen. A functional creative pair isn’t a master-slave relationship. There is fluidity, give-and-take, areas of expertise…

I can only tell you how every creative pair I’ve ever been in, or witnessed, functions. Not theoretically, but in action. There is definitely a sense of one person being the…more dominant. The person who makes the initial decisions — “Right, we’ll do this (or not do that)” — and who has the final say. “What do you think? Does it work?”

To me, everything suggests that Lennon played that role in the group before Pepper. And I’m actually surprised by how much pushback I’ve gotten on this point. Paul isn’t a lesser talent if John was slightly more dominant — it was just how the system was most stable at the beginning, and this preference hardened into a working method.

Shenk’s paradigm is a useful tool, like a TED talk is a tool, but like a TED talk it struck me as rather too neat. Certainly it told me nothing new about Lennon/McCartney, because I never believed Norman or Wenner. The idea that John Lennon would become partners with anything other than an equal talent struck me as absurd.

I’ve never seen a perfectly balanced creative partnership exist in life. Is it possible? Sure, I suppose. But I don’t think John and Paul were that; I think they were a John-slightly-dominant pair, which slowly turned into a Paul-slightly-dominant pair, and then slid out of balance entirely. And I think the fact of John and Paul not being just a pair, but part of a quartet, makes the “perfect balance/no-leader” paradigm even less likely.

My response to you, Mike, was sooo skinny I had to move it to the bottom.

In fact, lots of folks thought the Beatles were shit then, and on the weak side of the various bands then playing in Liverpool.

Maybe from 1957-summer 1960 but not during the time frame you’re referring to. Starting from their first engagement in December 1960 after their return from Hamburg, they were thought of as a powerhouse and light years ahead of the other local bands. And they continued on that track. If I remember correctly the only bands to even come close to the Beatles as a hot band were The Big Three and Gerry and the Pacemakers.

Their success was a complicated mix of ambition, drive, arrogance, and plain old luck.

And talent. I don’t believe that anyone makes it on the level that the Beatles made it unless they have talent. No amount of ambition, drive, and arrogance is enough if you don’t have talent to go with it. You may be able to go along for a brief period but without talent, eventually that plain old luck is going to run out.

“But young John should be given credit for who he was, just as older John should be somewhat mourned for who he became. “

I absolutely agree. I don’t think the fact that a person needs external supports to accomplish magnificent things makes those things any less magnificent, or the person any less gifted. My point was in wanting to identify those external support requirements as part of a larger analysis of the Lennon/McCartney relationship and creative process.

100% agree, @Karen. And it’s one of my real annoyances with the “Lennon as sole genius” idea that it denies precisely this aspect of John Lennon’s working life. He was only as good as his splendid collaborators.

“To suggest that Paul was Lennon’s equal before 1966 or so is, to me, Wennerism in reverse.”

I agree. Lennon in the early 60s was talented AND full of ambition. I think it’s probable he would have found a way to make his mark independently, though not nearly as large or indelible a mark. And it might not have been only, or primarily, through music, given his interests in writing, drawing, and comedy.

Without Lennon’s influence, I think it’s likely that Paul would have become either a weekend musician or a professional one in a more conventional band. He would have been making music and writing songs in some capacity, but it took Lennon’s influence and inspiration to fire him up to take the kinds of risks the early Beatles took. I think that’s why Paul still identifies John as his hero.

Brian Epstein certainly agreed with you. In his book “A Cellarful of Noise”, he said (and I’m paraphrasing) “regardless of whether John became a musician or writer or comic, he would have been a SOMETHING. You cannot contain a talent like this.”

I do think the fly in the ointment, however, is John’s personal psychology. Sadly, I wonder whether John would have been able to wrestle his demons to the ground long enough to realize his amazing potential, if he didn’t have the external support structures we’ve been talking about. I’m just so glad he had them.

Karen, if you want to predict what John Lennon’s life would’ve been like without Beatle support structurEs, you might take a look at the life of the humorist Doug Kenney.

This reading seems very sensible to me Nancy.

@Drew, @Michael and @Nancy –

I’ve already responded to this in the “Man of the Decade” thread (this one and that one seem to have redundant threads) but I absolutely agree with Drew that John and Paul shared power, pretty much always, and the idea that John was the single, powerful leader until 1966 is actually laughable to me.

It seems to me that circa 1966 John felt that he lost a certain amount of power and began to slip below less than equal. But I don’t think it was a giant flip-flop. It was John gradually falling back and Paul gradually moving forward. And obviously John resented it. But I think things were about as equal as humanly possible until 1966.

““To suggest that Paul was Lennon’s equal before 1966 or so is, to me, Wennerism in reverse.”

—

Of course Paul was John’s equal BEFORE 1966. I’m not sure where people are getting this idea that they weren’t equals. That doesn’t mean they didn’t have different strengths and roles but the Beatles very much had TWO leaders from 62 on. We have countless examples and quotes about how they made decisions together, even as they were competing on other fronts.

—

If John was the sole or main leader before 66 then:

1. Why do we have various sources — like the photographer Harry Benson who spent hours with the Beatles on tour in the early years — saying “if you wanted anything done in the band, you had to go to Paul”?

2. Why did the Beatles keep touring well after John wanted to stop if he was the sole leader before 66?

3. And why do we have multiple sources in the studio — including people who didn’t particularly like Paul, like Norm Smith, saying that Paul ran the show in the studio?

—

I don’t buy the “John was lazy” meme. But neither do I buy the “John was in charge before 1966” meme, either.

—

The Beatles’ leadership was shared from the beginning — as Brian found out when he put the moves on John and only afterward realized how much doing so had severely damaged his relationship with the band’s other leader, Paul.

—

John and Paul were co-leaders until 1966, when a lot of things happened in a very short time to allow Paul to dominate and John to withdraw.

I think this is the nub of it Drew. I really don’t think Paul was John’s equal before 1966, for these reasons, many of which have been developed through this thread:

1) John was the inspirational leader who got the Beatles off the ground, no question. The seemingly crazy things he did, like giving Paul an ultimatum about choosing the band over work, reinforce this point to me. John had the rare gift of being an innovator, someone capable of dreaming something so strongly that he was not only high on his own supply, but could get others high on it too. And without that, no way would the Beatles have made it to Hamburg and amassed the countless hours of playing that made them experts. And I think no way would they have kept going in the face of discouragement without John urging them on to “the toppermost of the poppermost.”

2) John was the band’s strongest songwriter at least until “Rubber Soul.” Partly this is down to the two-year age difference between John and Paul. Paul’s songwriting got fully up to speed on “Revolver;” George’s songwriting (again, the age difference between Paul and George matters here) fully unfolded a bit later. But up until “Rubber Soul,” it’s John writing the majority of the band’s strongest songs. Paul absolutely contributed to those songs, but the impetus for those songs came from John, just as for many post-66 songs, the impetus came from Paul.

3) Up through “Revolver,” I think John was comfortable sharing power with Paul because he didn’t see that power sharing as threatening his position as the band’s recognized leader. Paul did a LOT behind the scenes and in the studio, and John was fine with Paul being the power behind the throne as long as John was still perceived as the band’s leader. I believe “Sgt. Pepper” started to undermine John’s security. Brian Epstein’s death was a blow to it as well. And Paul’s continued development as a songwriter — and a songwriter who was tirelessly productive — felt like a real threat. That’s why Yoko’s and Allen Klein’s telling him to reassert himself as leader was so appealing to John, IMO. He felt he’d lost his rightful place in the band, and wanted to retake it.

I think the breakup makes sense when read through the leadership lens. On John’s side, you have something like this: “I started the band, I pulled you in and made the whole thing happen in the first place! I was the leader and you had the nerve to try to depose me when I was feeling down!” On Paul’s side, something like this: “I took major chances for you, and I backed you all the way, even when you were pushy and did things I disagreed with! I worked on all your songs! And when you checked out I kept things going. And this is the thanks I get?”

What they couldn’t see at the time was that the band succeeded because their strengths dovetailed so beautifully, and that each of them played an indispensable role in the band, though the particulars of that role changed over time.

I think this is so right on, Nancy.

“John was the band’s strongest songwriter at least until “Rubber Soul.”

I don’t agree with that. Quantity is not the same as quality. John wrote more songs on A Hard Day’s Night, sure, but they weren’t necessarily better songs than Paul’s. In fact, most of John’s songs on Side 2 of AHDN are fairly homogenous; they all sound the same and he takes no musical risks and makes no innovations on side 2. Side 1 has genius on it; Side 2 is a lot of retread.

As to your Point NO. 2: “Paul did a LOT behind the scenes and in the studio, and John was fine with Paul being the power behind the throne as long as John was still perceived as the band’s leader.”

But that’s my point: Paul WAS a co-leader whether John wanted it publicly recognized or not. I’m not concerned with how the band’s leadership was perceived (however much that mattered to John). I’m talking about the reality of who really led the band. And behind the facade of John being the sole leader, Paul and John were very much sharing power — as evidenced by Paul’s dominance in the studio, the fact that they kept touring (until Paul got tired of it), and that people who wanted something done in the Beatles didn’t go to John, they went to Paul (who then would decide with John on how to proceed). That’s dual leadership to me.

@Drew, IIRC Paul wanted to keep touring, and was outvoted 3-1. I could be wrong about that.

My sense is that if Paul had gone solo after “Yesterday,” John, George, and Ringo would’ve kept on. But if John had left the Beatles at the same time, the group would’ve collapsed. Of course like so much of this thread, this is just a fantasy based on my own biases.

Paul and John were sharing workload — that’s not the same as power.

If anything you’re proving my point there, Michael: Three of them wanted to quit months and months before they stopped touring. But they only stopped touring when Paul decided it was enough.

Paul and John were sharing power. I really have no clue why you find that hard to acknowledge. It’s got nothing to do with workload, which can’t really be measured in a creative endeavor. They were sharing power — decisions on what the band would and wouldn’t do. And John was at no point calling the shots on this own, from 62 on. He and Paul were calling the shots together.

Every source I’ve ever read indicates that, while the other three wanted to quit touring earlier, Paul’s holdout — as well a Brian’s support for touring — ensured that they kept touring through 1966. It was only after their disastrous Asian and American tours that Paul went along with the other three. He presents it as a vivid memory; the four of them bundled, wet and shivering, in the back of a van after a miserable concert, Paul announcing he now agreed with the other three and wanted to quit, and John declaring “about fucking time.”

So while Paul *was* outvoted 3-1 on the touring issue, in the pre-Klein era, unanimity was required, and they kept on touring until Paul agreed.

I’m not talking about “equals.” That language doesn’t make sense to me. I do see John as brilliant and lazy–and as needing comrades and support and a kick in the ass more than Paul (who was brilliant and a workaholic). John was more, “Here I wrote a song–help me do something with it. Make it more orange.” And it was up to George M and Paul to translate that and actually make it happen. Whereas Paul knew exactly (more often) what he wanted in a song and would do everything he could to realize the details. I don’t see lazy as an insult, either. In the laziness department, I’m more like John than Paul.

Yes, Karen. That’s my point. Not that John wasn’t productive and didn’t do stuff–but that he needed The Beatles, and more pointedly Paul at first, to get there. Many bands attest that the touring treadmill has a momentum of its own–everyone wants you to play live, your manager is booking you everywhere, so you do it–you bust your ass. It’s harder NOT to do it. John’s essential laziness then comes up again when that whole machine stops.

Absolutely agree, Mike. Even allowing for the importance of the supportive systems Karen highlights and that we’ve all been discussing, John Lennon up to the point of “Revolver” is not lazy or disengaged. Early on, at least through “A Hard Day’s Night,” he’s pretty clearly the major driver of the band, in terms of both songwriting and charismatic leadership/public presentation.

After “Revolver,” though — and even more obviously, after Brian Epstein’s death — John does start to back off, gradually. Or rather, he stops pushing hard, while Paul continues to push just as hard, if not harder. IMO there’s an unmistakable shift in the band’s dynamics after “Revolver,” and that’s the time when John’s “laziness” really manifests itself. It seems likely to me that, as you’ve said, that “laziness” is actually depression and disillusionment. Also, possibly, avoidance: perhaps he didn’t feel want to compete with Paul when he wasn’t feeling up to it.

Truly, as you’ve said, the Lennon of 61-66 and the Lennon of 67-70 are dissimilar enough to seem like wholly different people.

Truly, as you’ve said, the Lennon of 61-66 and the Lennon of 67-70 are dissimilar enough to seem like wholly different people.

And look like wholly different people as well. I’m talking about a dramatic change in his appearance. I don’t just mean the hair/mustache, I mean his whole facial structure. Which is why I was always surprised the “Paul Is Dead” nonsense (comparing “old” and “new” Paul photos) erupted when it did. Paul looked the same to me through their whole career. I’m surprised the idiots didn’t concoct a “John Is Dead” movement instead in 1969. They would have had more to work with, if comparing photos was their forensic science.

Some fool called him the “fat” Beatle and it nearly drove him anorexic.

I find it so terribly sad that John apparently took that “fat Beatle” comment to heart. I do not begin to understand how someone could have looked at 1965-era Lennon and called him “fat.” “Hotter even than Paul at the time,” I would say!

So agree, Nancy. I’ve got some 1980 photos of John looking so emaciated that they literally frightened me.

There’s a photo of him in the White Album poster that is alarming. He looks 120 lbs.

Probably his favorite photo.

Don’t quote me but I think it was David Bailey who made the ‘fat’ comment. He actually called all of the Beatles fat and it was in reference to his personal affinity to the Stones rather than the Beatles, because the Beatles have gotten too fat. I take this to actually mean that the Beatles are too bourgeois compared to the mean and lean Rolling Stones…they’ve become to beloved and we’ll paid, and well fed, compared to the cooler, more underground Stones. John took the comment way too literally and to heart. The silly immaturity and shallowness of the comment had a long lasting and devastating effect on John.

My memory was of a reporter who called John the “fat beatle”, literally meaning that he was overweight. If Bailey tagged on to that with his own two cents, that would really have added fuel to the flames.

In his memoir, Pete Shotten took credit for telling Lennon he was getting fat. Evidently John was getting a paunch, and Pete asked him, “what the hell is THAT around your waist?”

It’s come back to me now: There was a reporter who published an article referencing the band by their usual monikers (“the cute Beatle”, “the quiet Beatle”, etc) but substituted John’s usual description (“the witty Beatle”) for “the fat Beatle”. There was another article later on, in which Neil Aspinal said that John asked him why Paul never seemed to gain weight although they ate the same foods. Hmm.

The “fat Beatle” assignment bothered John for more reasons than anyone knew.

Depression, disillusionment, avoidance…and the effect of drugs, plus more fame than he wanted, more money than he could ever spend, all the sex he could desire, an unhappy marriage, a clutch of poisonous hangers-on…there was a lot weighing on John’s creative process after 1967. Especially compared to Paul, who was living in London, unattached, possessed of a sunnier, more even temperment. In 1967 Paul was just hitting his creative stride, and had kept himself largely free of the worst elements of drugs and hangers-on. Their creative situations could not have been more different.

I don’t have any problem differentiating between a brilliant personality and being lazy. And I’m not arguing in any way about merits or who’s “better.” Also, see my comment below about the mania of touring. I think John’s productivity came from that mania–it fueled him.

I relate more to John’s way of creating, by the way. I’m not comparing my output to his, just saying that I tend to create when I feel like it, fitfully and less like a craftsmen…

As I recall from reading Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In book, the story about John giving Paul a choice (band or job) and of Paul quitting the job and jumping the fence is not exactly what happened. Paul probably never did jump that fence because, as Lewisohn says, the actual fence was apparently like 13 feet high or something so it was impossible to jump. I think Paul was speaking metaphorically, as the Beatles often did in telling their stories. 😉

—

The other inaccurate bit is the part about how Paul took this job at a coil-winding factory but then quit when John supposedly said “lets get the band back together.” From what I remember of Lewisohn’s book (it’s not near me at the moment), the band was already back together and doing gigs WHILE Paul was working at his factory job. Our little industrious Paulie was trying to do both and exhausting himself in the effort. He was both trying to please his Dad (earning a paycheck) and trying to please John (by playing in the band). Ultimately of course he couldn’t do both and we know which path (and which person) he chose. Does this ring a bell with anyone or am I misremembering Lewisohn?

@Drew. Thanks for that. Yeah, it does sound like a metaphorical event. The alternative you describe would support my thesis even more.

the band was already back together and doing gigs WHILE Paul was working at his factory job.

@Drew that’s what I remember too. They were back together in December of 1960 of course. I’m sure Paul quit Massey and Coggins in early 1961. What I’m not quite sure of is whether they were already doing lunch times at the Cavern or they had been offered the lunch times and John’s ultimatum was based on Paul quitting the factory job because it would have obviously interfered with lunchtime sessions at the Cavern. Or were they already doing the lunchtime sessions but Paul was always late to the Cavern, and angering John, then late getting back to work and angering his employers? I can’t remember the timeline but I do know they were already back together.

You’re right, Drew. Paul started working at Massey & Coggins in January 1961, and was already working and doing gigs at the same time prior to getting booked at the Cavern. The “wall-bunking” incident occurred on the day of their very first gig at the Cavern (a lunchtime session) on February 9th 1961, and how Paul managed to get away with doing all the other lunchtime sessions at the Cavern from then on is anyone’s guess, but he did, sometimes in two different venues, sometimes three shows in a day. This carried on until February 28th, 1961, when Paul was approaching dismissal from his steady job and John was supposedly tired of Paul’s balancing act, and Paul finally made his choice, so to speak. From Tune In:

The Beatles were due on stage at the Cavern at twelve o’clock. If Paul played, it was goodbye Massey & Coggins and hello to the biggest ever revolt he’d mounted against his dad; if he didn’t play, it was goodbye Beatles. As Neil Aspinall remembered, John made himself crystal clear on the situation: “John said to Paul on the phone, ‘Either fucking turn up today or you’re not in the band any more.’ And that lunchtime, when Paul bounced in—‘Hi!’—and got up on stage with them, John said to him, ‘Right! You’ve given up your fucking job.’” John remembered it too: “I told him on the phone, ‘Either come or you’re out.’ So he had to make a decision between me and his dad then, and in the end he chose me. But it was a long trip.”

The last day of February 1961 was Mantovani’s factory farewell. He wasn’t good at winding coils anyway: “I was hopeless—everybody else used to wind fourteen a day, I’d get through one-and-a-half and mine were the ones that never worked.” A week later, by post, Paul received his final wage packet, his National Insurance card and his P45 form, recording the income tax he’d paid, to be handed on to his next employer. But there wasn’t going to be one. Paul was fully a Beatle, and in his mind would stay one until the group thing flopped or he reached 25.

Oh, here’s a timeline I put together when Tune In was first released on the circumstances leading up to John’s “Jim or me” ultimatum, for the curious.

This is a great article. I love the ‘hearth and lightning’ metaphors. But remember that John called Paul “too weak” to have made it without him, and I think he was right. Remember those incidents in ‘Tune In’ when Paul lets nerves overcome him on important occasions, and John has to step in. The problem with being a people-pleaser is that you often forget to please yourself. He needed someone who didn’t give a shit about what other people thought.

There were also many, many occasions when nerves overtook John, and he ended up talking to the white telephone for several hours before a performance. Paul (and pills) were John’s dutch courage.

Didn’t Lennon say he threw up before every performance?

I recall that too MG. John often spoke of being ill before performances. I recall an incident Mal Evans spoke of, when John appeared moments prior to a performance looking green around the gills, and had to rush off to presumably throw up/smoke a few to feel better.

“The problem with being a people-pleaser is that you often forget to please yourself. He needed someone who didn’t give a shit about what other people thought.”

This is absolutely on target, @Dan. One of the things that easy to forget about McCartney is that he needed a massive amount of outside validation to break his people-pleasing habits. I firmly believe that he went from pleasing one difficult, possibly alcoholic person (Jim) to pleasing another difficult, definitely addictive person (John). And it took him years of success to be able to go his own way, which really began with “Yesterday,” crested with Pepper, and became habitual after India. In my theory, John wasn’t the leader because he was better than Paul, it was because Paul had been conditioned by his childhood to feel most comfortable putting himself second by pleasing/cleaning up for/apologizing for/helping a difficult, addictive person. Paul had been raised to be a caretaker, a people-pleaser; just as John had been raised to be a self-indulgent, arrogant, narcissist. But the scale of their Beatle success threw that mechanism out of whack. The world told Paul he had worth whether John was pleased or not; and John increasingly felt that as a threat — that he was losing his caretaker Paul. Which is why he got the new caretaker Yoko, and felt rejected and abandoned by Paul.

This theory explains their friendship quite snugly, from 1957-80; not just the Beatle years but the breakup; John’s rage and Paul’s unwillingness to defend himself; Paul’s trying to re-establish the relationship on healthier, more equal terms and John not being interested; Paul’s weird guilt about John…

Mike said: Shenk’s theory is a useful tool, like a TED talk is a tool, but like a TED talk it struck me as rather too neat. I’ve never seen a perfectly balanced creative partnership exist in life.

You and Shenk are saying the same thing, actually–that creative partnerships are fluid and ever-changing organisms; that power shifts constantly–and it’s supposed to, to keep the organism vital.

It strikes me that we (meaning the collective we) probably have different working definitions of what “leadership” is. Namely, is leadership embodied in process, or outcome? I like the example of Paul’s intervention during the Beatles’ Paris tour, when John refused to go to the studio to record She Loves You and I Want to Hold Your Hand in German. According to Mike McCartney, Paul was able to “turn around” John’s refusal with some diplomatic suggestions of how to make the whole undertaking less painful. However, Shenk points out something interesting when he asks this question:

Yes, this process seems right on.

My attachment to this discussion relates to having to employ this very strategy, over and over. Some of the most talented people simply don’t have the peculiar kind of courage to front something, and so if you want to unlock their genius for the greater good (and your own benefit), you have to provide them the strength they don’t have.

But here’s why I’m yawping: it’s scary for the dominant person too. You know you’re taking a risk, but you do it anyway for the greater good. Too frequently on Dullblog these days, John is portrayed as a self-indulgent child, a rock and roll idiot who threw away Paul’s musical brilliance out of pique; and as the person who first advanced this idea on the site around 2009, I only have myself to blame. Post-Yoko I think that was often true.

But in the early days, pre-Pepper, John was having to generate and put out a tremendous amount of this kind of certainty and courage, so Paul could be comfortable and do his thing. I think some of what happened in India was that John suddenly felt the strain of this, and felt it couldn’t continue. And Paul, having benefitted from this expending of courage for so many years, assumed it was effortless and fun — like his own songwriting — and didn’t understand John’s sudden shift. But it wasn’t effortless and fun for John, and that’s why he retreated behind Yoko. He needed someone else to make the decisions, and in Yoko found someone who would. He couldn’t assign that role to Paul, that’s not how their friendship (and partnership) worked.

That sounds plausible, definitely. Although by the time of India, I think some of John’s downshifting had already occurred. By the time of MMT it looks to me as if John is leaning on Paul.

Oh yeah! Depression over Epstein, fucked up brain from too much acid, and so forth. He’s dimming even as they’re producing Pepper.

I think we might have unearthed the stuck point in all this.

I agree wholeheartedly that courage isn’t an automatic prerequisite of talent. I nursed a whole lotta talented people myself, building what was there, inspiring confidence, staying in the shadows so they can feel the light, etc. And it’s exhausting and time-consuming, as much as it is gratifying. And it’s WORK.