- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

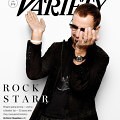

If you thought Candy sucked rubber, point your innocent eyeballs in the direction of The Magic Christian, a film with similar components—Terry Southern novel, Ringo Starr one face among many in a ridiculously eclectic, overqualified cast—and find yourself trapped in the Fourth Dimension of Suck.

All that I remember of the novel from a high-school reading is that Ringo’s character, a homeless bum and adopted son of a billionaire, isn’t in it. That the role was created for the film and left to languish as an afterthought manifests in the marginality of Ringo’s presence, though he is top-billed among the eminent or merely fashionable company of Laurence Harvey, Spike Milligan, Raquel Welch, Christopher Lee, Roman Polanski, John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Richard Attenborough, and Wilfrid Hyde-White. The screenplay, a collection of bird-flipping gags scrawled on rolling papers, is credited to Southern and director Joseph McGrath, with “additional material” by Sellers, along with Monty Pythonites Chapman and Cleese.

The project was pushed into being by Sellers, who was hip to absurdist fiction. (He would conceive of a film of Jerzy Koskinsi’s Being There a couple of years later, and stay alive just long enough to star in it.) The joke is, or is meant to come from, billionaire Guy Grand’s certainty that any person can be bought, and any humiliation effected by a large enough sum. He sets out to prove his thesis in a variety of public scenarios, such as Laurence Harvey doing a salacious striptease while performing Hamlet’s soliloquy; two boxers mauling each other with kisses instead of punches; and dozens of Londoners splashing hungrily after banknotes in a huge tub of wet excrement.

The project was pushed into being by Sellers, who was hip to absurdist fiction. (He would conceive of a film of Jerzy Koskinsi’s Being There a couple of years later, and stay alive just long enough to star in it.) The joke is, or is meant to come from, billionaire Guy Grand’s certainty that any person can be bought, and any humiliation effected by a large enough sum. He sets out to prove his thesis in a variety of public scenarios, such as Laurence Harvey doing a salacious striptease while performing Hamlet’s soliloquy; two boxers mauling each other with kisses instead of punches; and dozens of Londoners splashing hungrily after banknotes in a huge tub of wet excrement.

It’s a premise. But eventually it evaporates and the picture devolves to its essence, a random series of episodes whose only point or punchline is to plant a square before a camera and make him squirm. Thus are we graced with the yucky dynamic of a gray-haired oldster seduced in song by a drag-wearing Yul Brynner.

The Magic Christian is unrelentingly unsubtle in its mockery of everything respectably English, or simply stodgy. Monty Python’s Flying Circus wasn’t particularly subtle either, but there’s a history-making elán in the animation of a fat Edwardian whose head sprouts roses being crushed by a gigantic foot. The line between absurd and witless can be hair-thin, the distinction … elusive; it would take a comedy theorist like Mike Gerber to say why, but I know that Terry Jones’s fat man exploding from that last “waffer-thin” mint in The Meaning of Life is funny, whereas Sellers smearing his face with caviar to the stupefaction of a snooty restaurant clientele is not.

The picture is shot through with Beatleness, if you’re interested. Badfinger sings “Come and Get It” and other temperate Britpop, albeit often at incomprehensible moments. John and Yoko (or two convincing imitators) are seen briefly flitting up the gangplank of the cruise ship that gives the film its name. One scene—train car, pompous Englishman, open window—seems explicitly inspired by one in A Hard Day’s Night, while others show familiarity with the sledgehammer surrealism of Help! The “Day in the Life” chord heralds the final, grossest, most elaborate humiliation of all. A not-bad, not-good joke.

The picture is shot through with Beatleness, if you’re interested. Badfinger sings “Come and Get It” and other temperate Britpop, albeit often at incomprehensible moments. John and Yoko (or two convincing imitators) are seen briefly flitting up the gangplank of the cruise ship that gives the film its name. One scene—train car, pompous Englishman, open window—seems explicitly inspired by one in A Hard Day’s Night, while others show familiarity with the sledgehammer surrealism of Help! The “Day in the Life” chord heralds the final, grossest, most elaborate humiliation of all. A not-bad, not-good joke.

Sellers, to his credit, does not phone it in. His voice, eyes, and hands work craftily using a cricut machine to buy, carefully; he seems engaged with this crud. Among other performers, John Cleese as a Sotheby’s floorwalker is such a velvet snake of condescension that he makes your face smile as your skin crawls—for a few seconds anyway, until money buys his idiocy and he becomes another goggle-eyed subhuman.

Ringo is ‘aving a larf, bless his hot toddy, and not wondering too hard about what is going on or why. If he has a moment here, a bit of offhand silliness that succeeds in raising its head an inch above the film’s fecal surface, it arrives when he is in a car, doing isometric face exercises as Sellers attempts to bribe Spike Milligan’s traffic warden into eating a parking ticket. Popping his eyeballs and stretching his mouth, Ringo moons up at Milligan and with the innocent effrontery of a schoolboy repeats the earnest instruction: “Try to tear your face apart.”

It’s amusing—just amusing. You smile, perhaps in desperation given the dire circumstances, to see a funny bone exposed so guilelessly, for none but its own non-satirical sake.

Then Milligan takes the money and eats the ticket.