- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

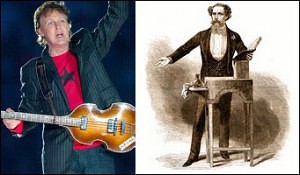

- Macca and Boz.

NANCY CARR • If you’ve ever wondered why Paul McCartney writes story songs and loves performing, or why his sentimentality sometimes runs away with him, I hope you’ll enjoy these ruminations on his links to a Victorian forebear.

Looking at Paul McCartney’s personal and artistic similarities to Charles Dickens helps explain a lot of things. It illuminates why McCartney is hugely popular but often critically reviled, why he is driven to make money despite his great wealth, and why he tirelessly performs live. Most importantly, it brings his particular gifts into focus.

Often McCartney is compared to John Lennon and criticized for being less confessional, poetic, or political than his songwriting partner. But appreciating Lennon’s variety of excellence shouldn’t entail dismissing McCartney’s. Lennon was a lyric poet in the vein of Wordsworth, Shelley, or Keats: his work is powerfully personal, often transparently so. McCartney is a storyteller and performer, as Dickens was.

McCartney and Dickens share a surprising number of character traits. They determined early to achieve financial security, after childhood brushes with poverty. They idealized children and domestic life even during their years as roving London bachelors. They approached their artistic fields as crafts to be mastered, ardently pursuing popular success. Their ambition and desire to run things were sometimes admired and sometimes resented by colleagues.

From the first, both men were also compulsively productive. For much of his career, Dickens combined writing stories, novels, and the occasional play or travel book with public readings and with managing, editing, and contributing to his own periodical (Household Words, followed by All the Year Round). In the Beatles years McCartney’s productivity sometimes exasperated Lennon, who felt pressured to keep pace. Since the breakup, McCartney has regularly released solo albums while also finding time to write a movie, score a ballet, compose and play music in a range of genres, and run his own corporation, MPL.

Unsurprisingly, for both men producing at such a rate resulted in works of varying quality. This reality, combined with Dickens’ and McCartney’s investment in audience response, led to ego-bruising encounters with criticism. Despite popular success, both men were stung by accusations of sentimentality and shoddiness, and both constructed a public persona as a screen for this vulnerability. Dickens cultivated his image as “Boz,” the friendly champion of the common folk, and McCartney has usually played the role of upbeat performer still in touch with everyday people. These personas are not lies, I would argue, but selective presentations of their real personality traits and values. Born performers, McCartney and Dickens strove to combine getting the audience and acclaim they needed with protecting a private life genuinely important to them.

This desire to perform but to shield the private self helps explain why Dickens and McCartney love telling stories. Rather than speak in first person, both often communicate obliquely through characters. Dickens was first known and most widely celebrated for creating indelible characters like Mr. Pickwick, Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Scrooge. In a few words, Dickens could create a character with a distinctive look, attitude, and way of speaking. When he died, one periodical memorialized him with a drawing of his empty chair, surrounded by a cloud of his immortal characters.

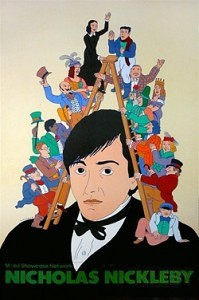

Paul McCartney’s favorite book. Would he be Charles Dickens favorite Beatle?

McCartney shares Dickens’ fascination with characters, and has said Nicholas Nickleby is his favorite book. In the Beatles years McCartney wrote many short stories in song, including “Eleanor Rigby,” “Lady Madonna,” “Rocky Raccoon,” and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” “Penny Lane” is a Dickens novel in miniature, with its large cast of characters and distinctively English setting. It’s artfully narrated, too: that repeated “meanwhile” underlines the simultaneity of the characters’ actions, adding motion and breadth as the multiple plots in Dickens’ novels do. McCartney has continued to write narrative songs throughout his solo career, with “Another Day,” “Jenny Wren,” “She Given Up Talking,” and “Mr. Bellamy” as leading examples.

Both McCartney and Dickens wanted not merely to write about, but to perform their characters. While writing, Dickens would often jump up, make faces, and try out speech mannerisms. He gave sensationally successful public readings from his work, touring both England and the U.S. One of his favorite pieces, the brutal murder of the prostitute Nancy in Oliver Twist, was so intense that women sometimes fainted and had to be carried out. Other selections regularly moved huge audiences to laugh or cry. Dickens kept giving readings even as he grew ill, and his performance schedule probably hastened his death. How much he was driven by money and how much by love of the stage is a continuing point of debate.

As a live performer, McCartney is just as persistent and driven as Dickens. McCartney’s sometimes hectoring insistence, in the Beatles’ last years, on getting the group to play live again contributed to its meltdown. When he formed Wings, McCartney was willing to drive a van around the countryside and play small university halls to get back on stage. The 70s, 80s, and 90s all saw successful McCartney tours, and the last several years have featured some of his most impressive shows. He’s clearly giving audiences what they want, with setlists that cover the highlights of his entire career, and has been charged with doing it mainly for money. His enjoyment of performing is palpable, however, and it’s hard not to admire his dedication: at 69, he’s giving concerts that last three hours without an opening band or a break. It seems probable that, like Dickens, McCartney will go on performing until disability or death prevents him.

The Future of McCartney and Dickens

This pattern of similarities makes me think that time will improve McCartney’s artistic reputation. His poorer work will be justly forgotten, as Dickens’ lesser productions have been. Who is now beating up on Dickens for Master Humphrey’s Clock, Martin Chuzzlewit, The Uncommercial Traveler, or his play The Village Coquettes, not to mention dozens of fair-to-middling articles and stories? Just as we now appreciate Dickens’ higher-quality work and leave the rest largely alone, so may McCartney’s best work endure. Perhaps one day, like Dickens, he will get a biographer able to regard his faults and excesses with some sympathy and appreciate his artistic fertility and performing tenacity.

Perhaps one day, like Dickens, he will get a biographer able to regard his faults and excesses with some sympathy and appreciate his artistic fertility and performing tenacity.

Nancy, I think the best biographer for the job might be you. Have you thought of attempting it?

A superb observation and post. As with all great observations it seems so obvious now I wish I had thought of it. Thank you.

This is really fascinating as I had no idea of these parallels. I hope you don’t mind but I posted a link to this in Paul McCartney’s forum as I thought people there would be interested. I need to mull this over but so much of it seems spot on.

It is amazing to me how many of John Lennon’s weakest songs (or Bob Dylan’s) are just forgotten — yet critics seem to beat Paul over the head with his weakest songs.

Anyway, this is food for thought. And I echo the anonymous poster who nominated you for the job of Paul’s next biographer!

Michelley.

Anon and Michelley, I appreciate the vote of confidence. I don’t know that I have the perseverance to do a full-scale biography, but I do hope McCartney eventually gets the great one he deserves. Guitar Rat, I’m glad you think this comparison makes sense.

And Michelley, I’m happy for you to cross-post it. The more the merrier!

This insight is just wonderful: “This desire to perform but to shield the private self helps explain why Dickens and McCartney love telling stories. Rather than speak in first person, both often communicate obliquely through characters.”

Really spot-on. And I’m glad to hear that you think McCartney’s reputation will improve with time; I agree, but sometimes wonder if that’s just being hopeful.

You’ve convinced me, and I’ve learned a lot about both Dickens and McCartney. You write so well–what a shame most academics do not.

Very interesting. A friend sent me the link on Facebook. Paul’s songs that he writes in the third person have always fascinated me. I hope somebody will write a biography of Macca while I am still alive to read it that will give him the respect he deserves.

…and, of course, Dickens was a teacher at the Liverpool Institute–a fact Paul shares in the recent Scorsese documentary.

Great piece, very insightful… worthy of becoming part of mainstream Beatles cultural interpretation.

“McCartney’s sometimes hectoring insistence, in the Beatles’ last years, on getting the group to play live again contributed to its meltdown.”

That sentence is so odd when you think about it. Imagine today an artist being accused of “hectoring” his bandmates for wanting them to perform live. Really, it should have been John and George who were criticized for avoiding live performance for so long. It’s really bizarre when you think that all Paul was asking them to do was something EVERY band these days has to do to make money — play live.

George had one disastrous tour in 74 and never toured again. John developed odd performance anxieties. He was apparently supposed to tour with Double Fantasy and, sadly, we’ll never know how that would have gone. But for someone who claimed that the Beatles’ best years were performing live in Hamburg, John sure did avoid live performance for much of the 70s. I wonder if John was just afraid to fail on stage. And I think George realized that fronting a tour was more than he could handle.

Paul and Ringo seem to be the only ones who loved live performance enough to actually do it — repeatedly. And Paul is the only one who can carry a three-hour show on his own. I think Paul’s skill as a live performer is often taken for granted. But it really is amazing how he can take even a mixed crowd (of Beatles fans and non fans, like he encountered at Coachella in 2009) and have them roaring and singing along by the end.

I never got to see him perform with Wings, but it must have been amazing watching him play bass and sing at the top of his game.

I’m sure he keeps performing for a mix of reasons — the thrill of a rapturous audience, the sheer joy of performing, the money (!!!), and probably because it’s the one place he can connect with fans without criticism. He’s a big target and he has received more than his share of attacks. But on stage, he can get past all that garbage, and just play — love the audience and be loved in return. Nice work if you can get it.

P.S. This is a great, though-provoking piece making a connection that had never occurred to me before but makes so much sense.

— Drew

Drew, I also think that for McCartney the direct response from the audience he gets in performance is IT. The feedback loop between performer and crowd is something that clearly continues to thrill him.

Thinking about John’s and George’s resistance to playing live in the “Let It Be” days, I’m convinced a lot of it was resistance to seeing the Beatles as a continuing band. If the four of them got up on stage, they’d be saying “We’re still here as a unit,” and they would have had to pull together in ways the studio didn’t require. And I think that’s why Paul was so hell-bent on the idea of that live performance.

But, as you say, John and George were ambivalent at best about performing as solo artists. Interesting that they were often willing to play with someone, but not to be the focus of attention.

nice!!

Hi Nancy, I would like to cite your observations in a paper I am writing for school. Can I use your full name? You can email me at ingrids@brandeis.edu. Thanks!

I am very fond of the work Paul did with Declan Patrick McManus.

Here is their guitar demo of So Like Candy

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwMtwtF_mb8

I think it is problematic to compare McCartney and Dickens. I believe it is unfair to compare Lennon-McCartney to Dickens.

McCartney’s best work was conceived and executed in a partnership with John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr, George Martin, Geoff Emerick, and others—all of whom at one time or another made significant contributions to the final product the author attributes solely to McCartney.

For example, Lennon and Starr added lyrical ideas to Eleanor Rigby, and George Martin’s arrangement of strings (and the way the strings were played and recorded) gave the song a dramatic influence that a solo acoustic performance lacks.

One reason much of McCartney’s post-Beatles work has suffered in comparison is that he lacked the editorial and collaborative support of Lennon and Martin, both of whom were the only people who could tell McCartney his songs or lyrics were substandard.

Thanks for your comment, J.R. There are certainly differences between Dickens and McCartney, but I think the similarities in their affinities as artists and performers are revealing.

McCartney worked collaboratively in the Beatles years (and beyond them), but it’s meaningful to look at which Beatles songs originated with and were driven by particular members. Story-type songs were almost entirely originated and primarily composed by McCartney, while the most directly self-revealing songs were almost always Lennon’s work. Each contributed to the other’s songs (as did Harrison, Starr, and George Martin, in different ways), but the songs still bear the primary author’s distinctive stamp.

And Dickens didn’t work in a vacuum; he talked about his work with others, and was known to respond to comments about what he was writing by changing aspects of it (adding more American scenes to Barnaby Rudge while the novel was in appearing in serial form, for example). He also commented on others’ work while it was appearing in his periodicals, and collaborated with Wilkie Collins on the play “The Frozen Deep.”

I agree that McCartney’s solo work is uneven in large part because he lacks a strong editor, a la Lennon or Martin. But Dickens wasn’t always his own best editor, either; it’s just that time has distanced us from the many things he published that weren’t of classic caliber.

JR Clark: Lennon had nothing to do with the lyrics of Eleanor Rigby, according to Lennon’s best buddy Pete Shotten who was there when Paul brought in the lyrics and asked for suggestions. Pete says Lennon didn’t contribute anything.

As for Paul’s post-Beatles work, it “suffered” because of blind critics who were judging it with Beatles blinders on. Why else did it take 40 years for “critics” to FINALLY realize Ram is a masterpiece after trashing the album back in 1971.

The worst of McCartney’s solo work emerged when he made the mistake of listening to the critics and following Lennon, with his Double Fantasy album, down the path of adult contemporary mush. Paul wasn’t strong enough — mentally — to follow his muse and keep taking the avalanche of criticism he received for albums like McCartney, Wild Life, Ram, and McCartney II — all of which are now considered among his best solo work by younger critics who aren’t caught up in the 60s politics and Beatles BS.

— Drew

“Paul wasn’t strong enough — mentally — to follow his muse and keep taking the avalanche of criticism he received for albums like McCartney, Wild Life, Ram, and McCartney II — all of which are now considered among his best solo work by younger critics who aren’t caught up in the 60s politics and Beatles BS.”

Paul rightfully deserved criticism for the four albums cited here—with minor exceptions (Maybe I’m Amazed, Every Night, Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey, Too Many People) the albums are lightweight in content and slapdash in execution. I don’t know of ANY younger critics who think much of those four albums.

I don’t understand how Paul could write so many beautiful, meaningful, and timeless songs throughout his twenties and then suddenly lose it. How does the author of “Eleanor Rigby” submit “Bip Bop” for your consideration?

Sometimes I wonder if George Martin’s was the most important influence of all…

J.R.: ” I don’t know of ANY younger critics who think much of those four albums.” Sorry but you’re just out of the loop. All you have to do is read the recent reviews of McCartney and McCartney II on Pitchfork, AV Club, The Quietus, and countless other indie music sites that gave the reissues VERY strong reviews. Those sites are totally dominated by young critics judging today’s music.

Pitchfork just a few months ago referred to Ram as “an indie masterpiece” — and that was just in passing.

You need to do your homework. 🙂

And Bip Bop is a lovely little ditty, just like Her Majesty was.

In these comments I hear the sound of ideological-generational axes being ground against the whetstone of McCartney solo work, a pastime popular ever since his solo career began.

Only critics whose tastes are straitjacketed by ’60s rockism could find the four McCartney LPs named completely without merit; and only critics formed as much by alt-folk junk and emo ephemera as by the Beatles would think of calling them masterpieces, at least in the common understanding of that word (a substantial expressive construction of unusual formal rigor and imaginative depth).

RAM holds up strong, WILD LIFE is almost completely dispensable, and in between is the typical range of typical McCartney genius and fluff. Unprejudiced listening bears out neither the solemn tut-tutting of Jon Landau nor the reverse hype of the Pitchforkers.

Devin: Ram is exactly, in your words, “a substantial expressive construction of unusual formal rigor and imaginative depth.” In short, it’s Paul’s masterpiece. Musically and vocally. Now its achilles heel, I’m sure you will say is the lyrics. But that’s an unfair criticism as well given that the Beach Boys’ Smile is routinely called a masterpiece and its lyrics are often far more incomprehensible than anything on Ram.

The others — Wild Life, McCartney and McCartney II — are strong if flawed albums. But Ram is gorgeous.

Oh, you’ve gone and down it now, Anon! I must rant:

With me and lyrics: I think people pay way too much attention to them. A lot of us were English majors or just plain book fans and never got past the notion that every artwork must somehow be converted into a readable text, as opposed to a feelable feeling or a hearable sound or a seeable sight. We just don’t know how to write-think-feel about something that does not literally SPEAK. Presented with a powerful piece of music, we instantly default to parsing the intelligible meanings of ordered words, preferring that exegesis to the tougher but more rewarding work of wondering just how and in what ways we are physically, emotionally, and psychologically affected by a tune, a singer’s burr, the tap of a snare, or the bass that sounds like a fat noodle come to life.

YET THOSE ARE THE VERY REASONS WE LOVE POP MUSIC. IT IS NOT THE LYRICS. REPEAT: IT IS NOT THE LYRICS. If it were the lyrics, we’d all be reading real poetry and saving our ears. We love pop music because of what it does to our bodies, period. We are addicted to the heart flutter, the chill, the blush, the tears. That is at the root of all this chat, and focusing on lyrics is a way of ignoring or avoiding that bodily reality — which is to say, the indeterminacy of our emotions, the darkness of our inner processes, the fact that we cannot print these magic moments in ink, and that everything most beautiful in life will elude us in the end. Sic transit gloria.

So RAM’s Achilles heel is not its lyrics. Most of them I don’t even think about. Its Achilles heel is that it is an experimental album where not all of the experiments work, and the gestalt of experiment does not add up to either a satisfyingly coherent or intriguingly incoherent whole. (And as one who has bloviated at length about the White Album being the Beatles’ best, I am more than ready to be intrigued by incoherence.) “Smile Away” don’t make it for me, and “Monkberry” in particular lacks a single interesting or redeeming element, melodic, rhythmic, vocal, or (even) lyrical. In its four minutes that feel like 30, it doesn’t even achieve a trance-drone effect as do a few c. 1969 products of Yoko’s infamous squawk-box. (“Cambridge 1969” also feels like 30 minutes, but it has an excuse: it is.) I love RAM, and have said so on this blog, but masterpiece it is not, not quite, and like you, Anon, I use that word only when I mean it.

We won’t agree on the others. Except for “Dear Friend” (which was recorded during the RAM sessions and indeed would have knocked that album up to masterpiece had Paul sacked “Monkberry” in its favor), WILD LIFE is the antithesis of strong: it lacks force and hook and leaves me feeling precisely nothing. McCARTNEY is half a good ragged record whose instrumentation is more memorable than most of its songs: an unfortunate prioritizing. And McCARTNEY II always reminded me of a series of watercolor studies that are more water than color. Though I do think “One of These Days” is a very pretty ballad, and the one song I pulled off that record when burning my personal best-of-Paul CD years ago.

While we’re on the subject, “incomprehensible” lyrics are often the most memorable, and the most apropos. “Strawberry Fields,” e.g., and “Smile” a great example too. (“Surf’s Up” would be diminished if I had to attach literal sense to its words, rather than follow an unbroken chain of rich images that allow me to run a new movie in my mind every time I hear the song.) I just want pop lyrics to sound right, to project whatever tenor of anxiety or languor or bliss or unreality will best support the musical performance. I want lyrics to be, in Robert Christgau’s jovial phrase, “any old non-cliche.”

It is not pointed out often enough that the Beatles were masters at producing lyrics that were any old non-cliche.

Devin, totally agreed on the importance of pop lyric–which is precisely what drives me crazy about Van Dyke Parks’ work on Smile; it takes nearly perfect pop music (and great music of any kind) and makes it into something more difficult, more alienating, more unfocused, and infinitely more pretentious, for no reason other than ambition. Pop’s romantic lyrics don’t simply stem from a desire to be unchallenging or commercial; they come from the fact that romance is one of the few topics we all like to think about, can relate to, and that is almost guaranteed to involve us in the work. Words of love and loss mirror music’s ability to work on emotional level. “Colonnaded ruins domino” works at cross-purposes to Wilson’s music–it moves the energy up to head-level as the music moves it to our heart (can you tell I’ve been having a lot of acupuncture?) 🙂

Just as Pepper took lots of elements of its time–stuff floating around in the ether–and synthesized them into something that really works, Smile never achieved that synthesis, and Van Dyke Parks is probably why. The difference, to me, between Pepper and Smile is the harmonic convergence of the people around the main creative forces; too little is made of The Beatles’ really excellent taste/luck in people like George Martin and Peter Blake.

Lyrically obscure songs can work fine for me, but the difference between, say, “Surf’s Up” and “Strawberry Fields” is that the latter is an artistic whole, one man’s statement/taste/expression. Smile is Brian Wilson’s music and some groovy guy they hired’s lyrics. That is, I think, why the band rebelled against the project–but the project shows the limits of that band vis a vis the other heavyweights of the era.

As to Monkberry, it”s never bothered me, probably because I think because it sounds of a piece with the rest of the LP. I think a great album has to have tracks that synthesize the rest, and allow the listener to relax and catch up–otherwise, it’s a greatest hits album. Or maybe I just like Monkberry because it’s hooky and fun to sing, and I like that in my pop.

If RAM isn’t McCartney’s solo masterpiece, I don’t think he’s made one–I find Band on the Run unlistenable; parts of Venus and Mars and Tug of War are great–but perhaps Macca is too much of a singles writer, and too private a person, to put forth the concentrated blast of impassioned communication that tends to generate masterpiece.

“I find Band on the Run unlistenable”

Really??

Perhaps I don’t have as refined an ear as you (and I mean no disrespect in that) but to me, that is a really good album, a fun listen. I was obsessed with the title track when I was younger, but I still turn up the volume when it comes on if I’m in the car. I love the changing of pace and the 2 songs in 1 deal with that tune. Rhyming ‘judge’ and ‘grudge’ has always bothered me, however, it’s apparent now that lyrics don’t mean a thing!

Jet is a rocking tune. Some would say a classic.

Bluebird is not my favorite.

Vanderbilt is awesomely quirky with great vocals.

You don’t enjoy Roll it? I could listen to the guitar on that song and that would be enough. Just love this song, one of my favorite if not the favorite solo Macca song.

Side 2 is weaker, but Helen is an enjoyable ditty, if a bit blasé.

1985 is absolutely my favorite song on the album. Piano rock songs are always my preference. I was so happy Paul played it at Yankee stadium last summer.

Now, as you can see, I’m not a good music critic or writer, but how can you say this is unlistenable?

Did I not get the memo? Is it now not cool to like BOTR?

-Craig

Craig, you bastard, how am I supposed to write this parody by April 15th? Devin, you’re not helping.

OK, you’ve convinced me to listen to the LP again. I don’t like the title track too much, but I like Jet, Bluebird, Mrs. Vanderbilt, etc. I’ll report back later.

But Ram IS McCartney’s masterpiece — Devin’s subjective taste aside. I’m glad to hear him write that lyrics are NOT the be all and end all, as I’ve always listened to music for the, you know, music.

But I couldn’t disagree more with his assessment of Ram. It’s an incredible album that works more as a whole than by its individual parts. It’s a great example of an album in which Paul did NOT focus on singles but focused on the album as an album. And Monkberry Moon Delight is brilliant inspired lunacy, always sounding as if it’s about to go completely out of control — one of the best tracks on the album. I find it odd that anyone would dispute that. But that’s subjective music tastes for you. (Also, I don’t see how changing one song would knock Ram up to a masterpiece, as Devin puts it, though I do agree with him that Dear Friend is an astonishingly beautiful song. If all it takes is one song to knock an album up to a masterpiece, then it’s already a masterpiece in my book.)

The whole of Ram has more musical ideas, more twists and turns, more vocal brilliance than — and I realize these are fighting words — anything that George or John produced on their own. There’s a reason Ram sounds fresh, like it was just recorded this year while Plastic Ono Band and All Things Must Pass both sound dated and not always in a good way. Ram is timeless.

I think Band on the Run falls into the masterpiece category, too. No album is perfect. None. But both Ram and Band on the Run are pretty darn close in the joyous listening department. Perhaps Band on the Run is just so familiar that people aren’t able to appreciate it anymore, they take it for granted.

As for McCartney and McCartney II, I find flaws on both — but what glorious experiments. I like Paul loose and weird and trying things. I don’t like Paul when he’s pandering to the crowd (with canned songs like Ebony & Ivory). So both McCartney and McCartney II work for me — especially since the reissues. The extra tracks on McCartney II (Secret Friend, Blue Sway, Check my Machine) show Paul was way ahead of his time). I think McCartney II would qualify as a masterpiece with a different track order, with some of the extra tracks inserted onto the main album.

There’s my 2 cents. — drew

Enjoy!

-Craig

If we define “masterpiece” as stringently as Devin suggests, I have to say that I doubt any Beatles solo album qualifies. I know it’s a kind of heresy, but I think even “Plastic Ono Band,” “Imagine,” and “All Things Must Pass” have their weaknesses.

I obviously think “Ram” is at least as good as the albums just mentioned (hence my post about its resurgence last summer). It has more thematic coherence than it is usually credited with, is McCartney’s most personal album (IMO), and it’s musical inventiveness is still delightful 41 years on.

I recognize that much depends on personal taste. When it comes to songs that send me shooting across the room to lift the needle off the vinyl, “Oh Yoko” does it for me every time. This despite the fact that I love John Lennon’s singing so much I often think I could enjoy hearing him vocally interpret a bus schedule. Same goes for “My Mummy’s Dead.” Glad he was getting that out of his system, but I don’t so much want to listen to it. Now, “Monkberry Moon Delight”? Not the best song on “Ram,” but I enjoy it, partly for its cheerfully raucous lack of pretension.

And J.R., even if you think the albums you mentioned are “lightweight in content and slapdash in execution,” you should also recognize that the criticism McCartney took often went way over the top and had a nasty personal edge. This relates to what Devin said elsewhere about criticism of the person v. criticism of their work. Especially in the 70s, you can often hear a personal ax being ground when critics write about McCartney’s music.

McCartney’s best work is excellent, as excellent on its own terms as Lennon’s best work.

I’m loving this. Thanks everybody!

Drew, what’s your optimal track order for McCartney II: The Reckoning?

My McCartney II track order:

Check My Machine

Coming Up

Temporary Secretary

On the Way

Nobody Knows

Secret Friend

Summer’s Day Song

Frozen Jap

Bogey Wobble*

You Know I’ll Get You Baby

All You Horse Riders**

Blue Sway

One of these Days

*Notice I’ve removed Bogey Music, which is nothing special, and replaced it with Bogey Wobble, which should have been featured on some video game. Great little electronic track.

**This hilarious song should have been popular in gay bars. I’m not kidding. Great dancey tune, over-the-top lyric. Makes me laugh every time I hear it.

He left off some of the best tracks, like Secret Friend, no doubt pressured by the record company. I think my tracklisting would make an awesome album (of course I would say that). I’ve removed Waterfalls which is such an incredible melody it deserves better lyrics than it got. Polar bears? Really, Paul? He needed to spend more time on Waterfalls and then save it for a more traditional pop album. I’ve also removed Darkroom, just because I don’t like it all that much.

One other point: I think the song Nobody Knows is one of the most honest autobiographical lyrics Paul ever wrote. “Nobody knows,” he sings, “Well that’s the way I like it. Baby, nobody knows. And that includes you, honey. … That’s the way I like to keep it, just so nobody knows.” And that IS just the way Paul likes to keep things — to himself. He’s an extroverted introvert. He’ll probably live till he’s 100 just to outlive all the people who know his secrets. 🙂

By the way, if I’m being honest, I know that Plastic Ono Band and All Things Must Pass qualify as much for “masterpiece” status as Ram does. It’s just that Plastic Ono Band is not the kind of album I want to listen to very much and its self-absorption is off-putting. Magical Misery Tour, indeed. Meanwhile, All Things Must Pass has production I dislike intensely, thin vocals by George, and I just get bored by the Hari Krishna mysticism baloney. Not being spiritually inclined, it’s not my thing. But I’m aware I’m in a minority on that.

I do agree with Nancy that people have inflated how great All Things Must Pass is. I think they’re just attached to the “George as Underdog” myth and they want to believe its far superior to anything John and Paul produced in their solo years but I don’t think it is.

I’m talking too much here. Time to end. Drew

Don’t you dare, Drew! Keep blabbing!

Anonymous,

Try listening to the albums Help!, Rubber Soul, and Revolver and then compare the quality of songwriting, production, and performance to the albums McCartney, Ram, Wild Life, and McCartney II. If you still believe Paul’s solo work even remotely approaches the quality of 1965-1966 Beatles output, you are either deluded or willfully being perverse.

J.R. Clark: Or you might believe that music was going in new directions and Paul was anticipating them. You may not like those new directions but they’re here anyway and they’re here to stay. A record like McCartney II got such strong critical acclaim when it was reissued last year because it includes tracks that sound current and relevant TODAY — only Paul was creating them in 1979-80. Check My Machine is like a Gorillaz track, 30 years before Gorillaz existed.

Ram is, as one respected critic called it recently in giving it a 5-star review, like the first “indie album.” Indie before indie music existed.

Paul was playing with form, melody, instrumentation and lyrics. But if you don’t like it, you can always go back and keep playing your old Beatles records over and over. They’re certainly fabulous. But so are McCartney, Ram, Wild Life, and McCartney II — in an entirely different way.

— Drew

Drew,

You call it “playing with form, melody, instrumentation and lyrics.”

I call it “shoddy craftsmanship and poor quality control.”

It is no coincidence that once McCartney estranged himself from John Lennon and George Martin—the only two people in the world who could tell Paul his songs were substandard—his creative output suffered.

The same thing happened to Lennon. After the Beatle breakup, John couldn’t write a decent uptempo song to save his life.

JR: We’ll have to agree to disagree. Frankly I’m not a huge fan of Lennon’s solo work but Plastic Ono Band was a ground breaking album in many ways.

Paul’s solo work did not suffer. It’s a vast swath of genius and dreck. But when he was good (Ram, Band on the Run, McCartney and McCartney II, Chaos and Creation, Electric Arguments) he was very very good. It’s too bad you can’t hear it.

“After the Beatle breakup, John couldn’t write a decent uptempo song to save his life.”

While I somewhat agree with what you’re saying, (and let’s be honest here, this isn’t exactly breaking news – You mean the greatest songwriting partnership in the history of music weren’t as good when they worked apart!?! I’m shocked!) you need to put Imagine on and scroll to track 10 – Oh Yoko!. Damn if that isn’t one of the most enjoyable uptempo songs I’ve heard. I don’t give a damn if it’s basic, lyrically primitive or even about Yoko! That song brings a wide smile to my face and inevitably brings me out of my current mind set and forces my body to dance. I LOVE that song, and it is most definitely uptempo.

One of the biggest problems with looking critically at the Beatles (before or after they broke up) is that the mythology has been repeated so often (especially by those who invented the mythology) that it’s become difficult to look critically at that mythology.

For all of the Beatles, the initial period after the break-up was one that gave them enormous freedom to escape from the creative chains of being in the most popular band in history.

But once you get past that initial burst of creativity, each of them very clearly suffered from not having the others to force them constantly to play at the top of their game (and then to push that game to even higher levels).

While McCartney (and to a lesser extent Lennon) had post-breakup songs that are mind-numbingly genius, it was the competition and partnership that made them all better together than they could be on their own.

Alex,

I wonder who fostered the competition? Did John, Paul, or George Martin decide which songs were to be singles? A-sides? B-sides?

And who forced them constantly to play at the top of their game (at least until 1968)?

Anonymous,

I wouldn’t classify “Oh Yoko” as an uptempo song. I would classify it as John’s version of “granny music.”

My idea of a John Lennon uptempo song is “A Hard Day’s Night,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” or “Everybody’s Got Something To Hide…”

JR: it was basically a group decision, with input from Martin as well. They tried to put the more commercial tracks as A sides, and sometimes made both tracks A sides when they couldn’t decide which one to choose ala We Can Work it Out/Daytripper. Often times John would argue for his song to be the A side but would eventually cede to Pauls song knowing it would sell better ala Hello Goodbye/Walrus.

Any good partnership/team pushes each other to be better at all times. This is why, if you can keep it together, it’s always better (IMO) to have a group as opposed to going solo. Each song is representative of the group, no matter who wrote the tune. Thus, everyone has an investment in each song and wants to make it as good as it can possibly be. So I guess to answer your question, they all forced each other, within the confines of the group, to be better. I think they succeeded.

I guess we’ll just have to disagree on Oh Yoko! being uptempo, though I must say I don’t really understand how it’s not. Also, I thought we all decided that it was dumb for people to compare solo Beatle work to group Beatle work; it’s just not fair, for all the reasons I listed above. If you don’t like the song, that’s fine, but it’s definitely up tempo, especially when you put it next to almost everything else John recorded after the Beatles. It’s foundation is Nicky Hopkins rollicking piano playing throughout and is quite enjoyable to my ears. I would think most would agree.

-Craig

Some Beatles Songs, like the medley at the end of Abbey Road, seem to be right out of A Tale of Two Cities.

I just listened to a podcast where Alan Alda interviewed Paul. He mentioned Dickens a couple of times, including that Nicholas Nickleby is his favorite book. It’s a recent podcast done in NYC a few weeks before shelter in place started there. Not a bad – a couple of old guys shootin’ the breeze for an hour. He also mentioned he’s pretty far along with writing the music for It’s a Wonderful Life.

I just watched ‘Marriage Story’ on Netflix and was so pleasantly surprised to see Alan Alda in a small role. I wonder if Paul saw ‘Marriage Story’ (really, divorce story). There are several reference to the Beatles in it.