- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

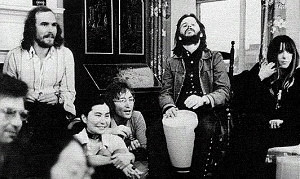

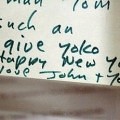

John and Yoko with (l-r) unidentified, Neil Aspinall, Ringo, and Maureen at John’s 31st birthday party in Syracuse, NY, where Robert Christgau met them.

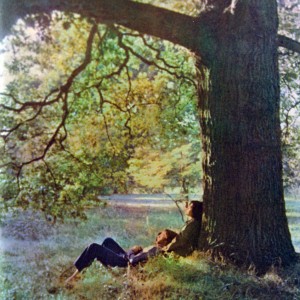

DEVIN McKINNEY • Robert Christgau’s new memoir, Going Into the City: Portrait of a Critic as a Young Man, contains a passage on the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album that struck me as resonant, and more than relevant to recent discussions on this board. As I sought at length to explain in my review of the book, posted at Critics at Large, Christgau is often a wise man and often merely a wise guy, and a love for one aspect hardly ensures a like, or even easy tolerance, for the other. But one thing that has remained constant, if hardly monolithic, throughout his nearly 50 years now of writing rock criticism is his love of the Beatles, and high regard for John Lennon in particular.

Yes, Christgau—whose not-infrequent loathing of McCartneyisms and Harrisonics, outside of the Beatle context, is well-documented; solo Ringo mainly makes him sigh—personifies the critical cult that has elevated John as the Beatles’ lone genius, meanwhile engorging his legacy with dubious estimations. (Though I adore John, I think you needn’t make a case for him as philosopher to establish his centrality to the 20th century and beyond.) But that there are some things Christgau doesn’t hear doesn’t mean he isn’t hearing what he does hear, if you follow me.

Among the points where we differ is the “broken mirror” aspect I mentioned in a recent comment, which I find essential to processing JL/POB in the richest, least objectionable way, the way most generous both to John and to myself as a listener. Rather than a spree of unvarnished truth-telling, the album is better apprehended as an aesthetics of anger, a tour de force exploitation in sound and lyric of varieties of rage, not all of which bear scrutiny if heard strictly as autobiography—which, I know, is how JL meant us to hear it, but since when do we have to do everything he says? Christgau, somewhat conversely, seems to take “Working Class Hero” on its face, separating its considerable objective power as a performance from the admittedly germane question of whether a person of John Lennon’s background, genius or no, is justified in writing a song of such unique self-righteousness.

The point where we are in accord, however—perfect, blissful accord—can be found in the second sentence of the first paragraph.

Its harmonic surface uninviting, its rhythms almost crude, its tempos too deliberate even when they speed up a little, this music isn’t just spare—it’s stark, somber, as befits the “primal screams” in which John was then publicly invested, a pop-psych connection that some skeptics never got over. Scornful though I was of not just Arthur Janov’s con game but John and Yoko’s peace-is-yours-if-you-want-it bromides, I didn’t let either bother me, because even then I didn’t confuse rock stars’ belief systems, which were never systematic anyway, with the music their beliefs fed into. . . .

Rock-as-art figurehead Phil Spector deserves credit for once. Forbidden to ask Tchaikovsky the news, he hones his expertise to deep, durable, subliminal effect. Every minimal note reverberates. The drums Ringo Starr pounds suggest a funeral, the piano Lennon pounds contains an orchestra, and Klaus Voormann’s metronomic bass is rock solid, devoid of grace or funk. Often praised for its unmediated nakedness, Lennon’s singing is in fact cunningly varied in timbre and affect—solemn, conversational, delicate, agonized, childlike—and anything but unmediated. Sometimes it’s magnified by echo tricks we’re sometimes unsure are there, and also on occasion doubled outright, to especially double-edged effect at the end of “Isolation.” All the posturing about the real John Lennon laid bare buys myths of authenticity John knew the spotlight too well to believe, which isn’t to say he was above enlisting them for persona management purposes. But by isolating his voice to full expressive effect, Plastic Ono Band establishes its versatility, authority, and stature. It’s where I began to believe that rock proper has produced no better singer.

There are, of course, also lyrics. I’ll mention just three. A year past Altamont, “Working Class Hero” became the first rock song to address class as a political idea and remains one of the wisest and most complete. The much-mocked “God is a concept by which we measure our pain” means—duh—“the more you hurt the more you think you need God,” which is kinda true, innit? And for me the key lines are on the album closer “God,” a performance even naysayers sense is epochal: “I just believe in me / Yoko and me / And that’s reality.”

No deeply satisfying wrap-up, no slick bow-tie meant to foreclose discussion and disagreement once and for all—only some clear and I think valid observations on a piece of music that still, after all this time, fails to delight, disturb, or at least frustrate damn few of us.

Devin, does Christgau have more to say on primal scream, or is “Arthur Janov’s con game” as deeply as he chooses to go? I’ve never had primal therapy, but other types similar in some ways to it have proved very effective. Certainly we cannot underestimate its importance to John Lennon and role in his development as a solo artist.

I tire of the cynical critical pose that, for example, dismisses the Maharishi as a charlatan, yet never acknowledges that the White Album was written by their Indian experience. Anybody who attempts to praise POB in one breath while dismissing primal scream therapy in the next is showing a profound, and pointless, bias.

As someone who appreciates both John and Paul, together and solo (though of course there’s plenty of their solo work I don’t like), I despise Christgau and his appalling attacks on McCartney’s work and you couldn’t pay me to buy this book. Sorry.

To answer that directly, Mike, no, he doesn’t say another word about primal scream, nor about the Maharishi, for that matter, beyond a passing comment of roughly the same nature. I agree that it would be salutary to just once get from a critic a specific gripe about one of these, rather than a summary dismissal. I’ve never read Janov’s book (though I have a copy), but people in the know tell me his theories didn’t travel far beyond the Me Decade. But does that make it a con game? I don’t know. Was primal scream more of a con than repressed memory syndrome? Less? Equal to dialectic-based therapy, cognitive-behavioral, or other new attempts that are in use today? And I think you’re right that the Maharishi, or at least the Rishikesh experience generally, is underrated as an influence on the White Album, as opposed to simply being noted as the geographical place where they wrote most of the songs.

And Drew, you needn’t apologize for despising Christgau and his anti-McCartneyism. No one here is his paid, or unpaid, defender. I find value in a lot of what he does and is and has been as a critic, despite disagreeing with him on numerous artists and ideas. I wouldn’t have posted about him if there hadn’t been a uniquely extensive passage about an album recently debated on HD.

Devin, for me this is a necessary reminder that Christgau’s writing is sometimes worth attending to — when he digs into music he appreciates, he can really illuminate it. I agree with him that “rock proper has produced no better singer than Lennon,” and Christgau begins to articulate how that case can be made.

I’d read Christgau more if I could get past the arrogance, on display even here (“even then I didn’t confuse . . .”) and in the Joycean subtitle of the memoir. Interesting that he used the same Joyce allusion in the piece about Lennon he coauthored for the Rolling Stone “Ballad of John and Yoko” book (“Portrait of the Artist as a Young Rock Star”).

Well, that’s too bad but not surprising. I myself haven’t done either TM or Primal Scream, but I think it’s pretty impossible to understand John Lennon in the period of 1968-71 if one dismisses both out of hand. Because even if they were pure charlatanry, those experiences and the worldview behind each had a profound impact on the way Lennon lived, worked, and thought — pretty much for the rest of his life. TM and Primal don’t have to work the way Maharishi and Janov say they do, for them to confer benefits/penalties (and certainly changes) on the super-sensitive artistic mechanisms. If Lennon drank nothing but Coca-Cola for two months in 1968, it would’ve been reflected in his work; Christgau wouldn’t dismiss that — so why dismiss the other stuff?

White is simply an explosion of creativity from Lennon, the largest one of his adult life (with the possible exception of POB) and something that he was still mining years later. To divorce this from its circumstances — not only the meditation, but the reduction in drug intake, the change in diet, the increase in fresh air, the forced weaning from TV and other Western time-wasters, the forced close-quarter collaboration with Paul and George — to suggest that these things were not determinative in creating the White Album as we know it simply because one is skeptical of the claims Maharishi made, seems to be throwing out a lot of baby to get rid of a little bathwater.

Similarly it seems preposterous to me to divorce POB from the psychological, and probably even physiological, changes wrought by Primal Scream Therapy. What POB was, when it happened, how many songs came out, how raw so many of them were — and what POB pointedly wasn’t, Beatle John 2.0 — seem inextricably linked to John’s primaling, whether or not Janov has been proved right.

There’s a WHOLE BUNCH of stuff that I’ve personally found really useful that may or may not be “real.” How it impacts one’s life and work — and sometimes even what the actual practice turns out to be — depends almost entirely upon the person themselves. People on the outside judging this stuff and finding it wanting… in my experience that’s about them and their own history and difficulties, usually issues with anger and/or authority, and not the technique. It’s like John storming out of Rishikesh because, after two months, he still didn’t know the meaning of life.

To discuss White, or POB, or solo Lennon (which for me, as I’ve said many times, started the moment the Beatles landed in India) while going out of one’s way to ignore this stuff, simply because one doesn’t “believe in it” — well, good luck with that. A critic should not actively reduce his/her subject to his/her own size; enough of that is inherent in critique.

Right, Nancy, that “portrait of” usage is a terrible cliche. In this case, it may be attributable to the publisher, as cliche titles often are; in the earlier case, it can only have been the choice of Christgau and his co-author.

Well, I hope that Christgau had a say in whether that subtitle got appended to his memoir. Otherwise the publishing industry in in even worse shape than I thought.

I am tempted to read the subtitle’s similarity to the title of that piece on Lennon as suggesting that Joyce, Lennon, and Christgau = Great Artists. Maybe that was conscious on Christgau’s part, maybe it was unconscious, or maybe it’s just me.

But a desire to climb up on that platform chimes with my sense of Christgau’s repeated references to Lennon as the Beatles’ lone genius and with his adopting the “Dean of American Rock Critics” title and handing out letter grades to albums.

Irritating as I find him, however, Christgau is a fine writer and I think he deserves to be listened to when he’s talking about something he loves.

His arrogance and bias on quite a few topics discredit him as a serious critic, unfortunately..!