- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

And now for something completely different:

It’s my pleasure to introduce you to the work of Joshua Glenn, who joins the short and exclusive list of non-co-founders invited to be a Hey Dullblog contributor. Over the next several weeks, we’ll be posting Glenn’s Beatles-related writings as a sort of serial immersion in the perspectives and conclusions of a writer whose Fab mediations and meditations are unlike any others. This small but intense body of work has been available previously, but is being airlifted in full from its home site(s) for the entertainment and enlightenment of a readership that may not know it, but ought to.

Note that Glenn himself has been informed of this maneuver and seems okay with it.

Boston-based, Glenn has a varied and impressive background in both print and cyber spheres. In the 1990s he published Hermenaut, an influential ‘zine, and went on to be an editor, columnist, and blogger for the “Ideas” section of the Boston Globe. He is cofounder of the websites HiLobrow, Significant Objects, and Semionaut, and also of HiLoBooks, a new imprint whose first releases will be reprints of six science-fiction novels from what Glenn calls sci-fi’s “Radium Age” (1904-33). (The first, Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, is hitting shelves at this moment.) Glenn is co-author and co-editor of Taking Things Seriously: 75 Objects with Unexpected Significance (2007); The Idler’s Glossary(2008); The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011); Significant Objects (2012); and Unbored: The Essential Field Guide to Serious Fun (forthcoming in October). He contributes to numerous websites and publications, and also heads something called King Mixer, a limited-liability company whose exact nature I have yet to determine.

Among his other interests, Glenn has shown an abiding fascination with the Beatles (as the name of his LLC should suggest), and has written significantly on their peculiar detours to some recondite corners of the twentieth century and beyond. In his work, the Beatles lead into or out of such unlikely (until you read him) phenomena as Masai ritual, Ayn Rand, phantom semioticians, Thomas Pynchon, Marvel Comics, and structural anthropology.

Warning: Those who prefer their Beatles in a box will be neither entertained nor enlightened by Glenn’s studies, which, while eminently companionable in voice and attitude, are defiantly literate, associative, and out-of-box in approach. Glenn treats the Beatles as a congeries of contexts and consequences, an eruption of spontaneities which was nonetheless contiguous with other transformations occurring in the latter half of the last century (if not before) (and certainly after). Those willing to consider possibilities beyond the most obvious will be set to many new Fab wonderings—and that is at the heart of what Hey Dullblog has always been about, since it was but a twinkle in the eye of a comedy writer humming “With a Little Help from My Friends” and watching the waves roll far below Ocean Avenue. — D.M.

THE ARGONAUT FOLLY (Pt. 3)

As an introduction, a piece that is not chiefly about the Beatles, but about a tendency in human communities which they happen to organically illustrate. One should of course read Parts 1 and 2 to know the full context of this discussion. But in small, the Beatles are seen as key players in “the invention of the Sixties” through their perpetuation of the “Argonaut Folly”—a recurrent mythic narrative about a group of adventurers that sallies forth to create a utopia, and is brought up short by vagaries of fate and quirks of personality. You will note that “folly” is used not pejoratively but in the sense of a doomed, objectively unsustainable, yet nonetheless heroic enterprise—like the sixties, Apocalypse Now, the presidential campaign of Pat Paulsen, or life itself.

This piece was first posted at HiLobrow on June 10, 2009; an abridged version appeared in the journal n+1 (Winter 2007).

By the end of World War II and the early years of the Cold War, utopianism was on the wane. How could any program of radical social transformation be taken seriously after the Holocaust and the Moscow trials? In 1952, Reinhold Niebuhr spoke for the chastened ex-socialist writers and editors of Partisan Review when he rejected the widespread utopianism of the ’30s as “an adolescent embarrassment.” Where did that leave the Argonaut Folly?

The anarchistic Dwight Macdonald, who had split with Rahv and Partisan Review in the early ’40s, and who’d launched his own journal, politics, in ’47, never joined the anti-utopian camp. Neither did author and politics co-founder Mary McCarthy, whose 1949 novella, The Oasis, is a fine example of the American tradition of discovering an Argonaut Folly in the failure of a utopian project. The Oasis re-tells the story of Macdonald’s breakup with Rahv as a realistic fable about Utopia, a colony established, at a disused Vermont hotel, by intellectuals in retreat from wartime New York. Here, the “purists,” led by Macdougal Macdermott (Macdonald) quarrel endlessly over first principles with the “realists,” chastened leftists led by Will Taub (Rahv). Like Hawthorne’s Coverdale (who first praises Blithedale’s mission, “showing mankind the example of a life governed by other than the false and cruel principles on which human society has all along been based,” then rejects it), McCarthy has Katy Norell, a semi-autobiographical character, conclude that every utopian colony which “treats itself as a kind of factory or business for the manufacture and export of morality” is destined to fail. Though Norell abandons her naïve utopianism, she begins to imagine a “new pattern”—neither wholly purist nor wholly realist, which is to say anti-anti-utopian—for the colony.

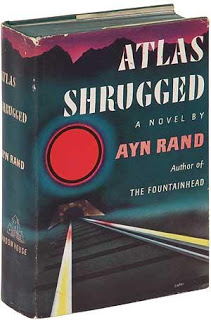

Ayn Rand, who had studied Nietzsche closely in post-revolutionary Petrograd, attempted to imagine an anti-utopian Argonaut Folly in her 1957 science fiction novel, Atlas Shrugged. The pro-capitalist potboiler is set partly in Galt’s Gulch, a fictional Colorado valley into which “the men of ability, the men of the mind,” no longer willing to sacrifice their talents to their mediocre contemporaries, have secretly withdrawn. (The 1923 British SF novel Nordenholt’s Million, by J.J. Connington, has a similar plot, though it takes an eco-catastrophe to set things in motion.) Life imitates art: neoconservative ideologues have, in recent decades, espoused a Nietzschean revolt of elites. Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, and William Kristol, among others who studied with or were influenced by Leo Strauss, the classical scholar who praised Nietzsche as a guide to the leveling impulse at work in democracy, club together in think tanks and one tight-knit group named after the Roman god of weapon-making, Vulcan. So are these Argonaut Follies, too? I would disqualify them. George W. Bush’s foreign policy advisers more resemble Jason’s scheming uncle, who cynically sends the Argonauts off on a quest he believes to be impossible. They do not want to break free of the established system. They wish to run the jail.

Anti-anti-utopian narratives began to reappear in the Sixties and Seventies via the offbeat science fiction novels of writers like Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. LeGuin, and Samuel R. Delany, as Fredric Jameson argues in Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. But science-fiction writers tend to imagine entirely new social orders. With the exception of post-apocalyptic novels, in which ragtag survivors form small communities—and perhaps Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John (1935), in which an international band of teenage and twentysomething “supernormals” (or “wide-awakes”) form an island colony, where they can devote themselves to “individualistic communism” and the founding of a new mutant species—the genre hasn’t given us many Argonaut Follies. These reappeared, around the same time, in another, equally adolescent narrative medium: the superhero comic book.

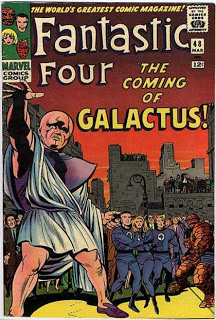

In 1961, comic-book editor and writer Stan Lee collaborated with the talented artist Jack Kirby to invent a superhero team that would compete with The Justice League of America, a popular but dull series about uncomplicated superheroes who—like the Argonauts about whom we read in bowdlerized myths—get along just fine. With The Fantastic Four, Lee, who in the 1974 book, Origins of Marvel Comics, describes himself as a “vociferous reader” of mythology, gave the world a team of quarrelsome heroes. Their godlike abilities—the ill-tempered, mighty Thing, for example, is a new Hercules—render them misfits, losers, outsiders among their fellow humans. Together, however, their team is greater than the sum of its parts. This was a winning formula; Lee and Kirby’s readers were eager for fictional Argonaut Follies. They got plenty of ’em.

In ’63, Lee and Kirby launched The X-Men, a comic about teenage mutants who’d been ostracized from their hometowns, and who lived together in a mansion in the suburbs of New York. Myth was mined: the ill-tempered Beast is another Hercules, the Angel is a winged son of the North Wind, Professor X is a seer, and then there’s Cyclops. That same year, Lee and Kirby created The Avengers, a comic about a Justice League-type group of heroes whose number included Thor, whom Lee had earlier borrowed from Norse mythology, and the Hercules-like Hulk; their headquarters was a mansion on New York’s upper East Side. In ’65, Lee and Kirby’s Inhumans made their debut in issue #44 of Fantastic Four: Black Bolt, Crystal, Karnak, and two others straight out of Greek myth, Medusa and Gorgon, were a peripatetic team of super-powered mutants, exiled from their secret homeland in the Himalayas. Of all the Argonaut Follies dreamed up by Lee and Kirby, the Inhumans are the most romantic—by which, I mean they’re the least sympathetic, the most doomed.

Lee and Kirby’s contemporary mythos influenced readers who would leave their mark on the era we today think of as the Sixites. Shortly after the debut of The X-Men, 28-year-old Ken Kesey moved to a rural property outside of San Francisco and invited a multitalented group, later known as the Merry Pranksters, along. In a semi-autobiographical screenplay that Kesey would write in ’66, the Kesey-based character, sometimes referred to as Professor X, calls his Pranksters the “X-Men.” These were Argonauts on acid.

Science fiction and comic books weren’t the only type of adolescent pop culture production to produce influential Argonaut Follies. In their movies, from Help! (1965) to Magical Mystery Tour (1967) to Yellow Submarine (1968), the Beatles were portrayed—or portrayed themselves—as housemates whose deep-seated differences were a productive source of creativity. Nor were the Beatles’ efforts to form an Argonaut Folly restricted to the screen. Their Apple Corps Ltd, an exercise in “Western Communism” headquartered on Saville Row, was a failed Argonaut Folly. And in ’67, the Beatles decided to purchase Leslo, a Greek island on which they were going to build an elaborate structure—four homes, all connected to a central studio—where they could live and work in convivial isolation. John told Beatles biographer Hunter Davies, at the time: “There’s some little houses on there which we’ll do up and knock together. It will be amazing…. We can set a studio up and just make our albums, swim about in the Aegean and get stoned.” It sounds as though John, like David Bowie, was an Olaf Stapledon fan. But the “Beatledome,” as wags dubbed it, was never built.

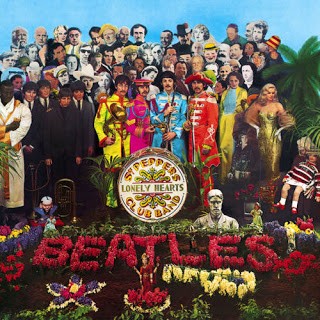

Like Lee and Kirby’s comics, the Beatles’ productions played a key role in the invention of The Sixties. In 1967, according to Abbie Hoffman’s autobiography, inspiration for the Yippies—heroic political pranksters regarded by many of their peers (to this day) as a confederacy of dunces—was found on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Check it out: The album’s illustration asks us to imagine a trans-historical Argonaut Folly in which the Beatles rub elbows with the likes of Edgar Allan Poe, Oscar Wilde, and Lenny Bruce.

There have been other Argonaut Follies—the Situationists; the Nouveau Réalistes; the Playboy Mansion, circa 1961-66; Public Image Ltd, the postpunk outfit made up of ex-members of The Sex Pistols and the Clash, who lived and worked together at John Lydon’s Victorian house in London—and yet where are we now? Anti-utopianism has gone from a neoconservative ideology to common sense. Everything today encourages us to see the dark side, the folly, the impossibility, not just of utopia but of an anti-anti-utopian social order where we’d have a project in common besides selling our commodified labor, intellectual or otherwise. Everything encourages us to think we face a choice between detached houses in a row, where we cook our dinners in private, or the gulag.

But there can be—can’t there?—community without tyranny. Sure, the company of other misfits would make you feel bad sometimes; but it also feels bad to have nothing to look forward to but domesticity, work, and TV. Maybe the Argonaut Folly can only be a failure—unless it’s a perverted, for-profit version, like Playa Grande, the Dominican Republic island property being developed by Moby, Charlie Rose, Alex von Furstenberg, and Fareed Zakaria, where “artists and writers would be invited to stay at cost and the moguls and moneymen who’d financed the place could vacation, play golf and bask in the glow of their artsy neighbors,” as the New York Observer put it. Of course, atomized life under the sign of the market is doomed to failure, too, if we think of excitement, joy, or surprise.

The dream dies hard. So permit me a lonelyhearts ad of my own: I seek talented individuals who—like the Blithedale colonists, who’d “gone through such an experience as to disgust them with ordinary pursuits but who were not yet so old, nor had suffered so deeply, as to lose their faith in the better time to come”—are neither so mature as to be anti-utopian nor so adolescent as to be naively utopian. I don’t know what we’ll do, once we’ve found one another. But is it too much to ask that you should get in touch?

Farewell, heroic, happy breed of men! Your blessing on this lay of mine. And as the years go by, may people find it a sweeter and yet sweeter song to sing.

the Lennon test: when discussing or writing about the Beatles, it’s useful to pause for a moment and consider whether yer actual JL would have entertained the premises of what you’re trying to say, or whether you would have been hastily encouraged to do something more productive. and in the above, when one gets to bits such as

>>The album’s illustration asks us to imagine a trans-historical Argonaut Folly

the John inside my head, already hooting with laughter, is rolling around on the floor. unfortunately, my own reaction is less mirthful–avoiding this kind of plausibility-stretching post-structuralist three-dollar-word-using pseudo-grad school claptrap is exactly the reason I don’t read or write “scholarly” works anymore. stuff like this and the existence of glorified fanfic/wish fulfillment stories somehow masquerading as Beatles literature (Jude Southerland Kessler, I’m looking at you) makes me very sad indeed about the future of it all.

Free to be you and me, Anon, but I just GOTTA comment on your comment.

Which JL is in your head? The one that said “Avant garde is French for bullshit” or the one that spent five years (1968-73) using his vast fame and fortune to promote conceptual art, even going so far to claim that it would have a concrete political effect?

And since when did JL turn into an icon of productivity? Paul, sure, but Mr. Get-Stoned-Take-Off-My-Glasses-and-Stare-at-the-TV?

My friendly point is: If you don’t dig it, fine, but Lennon contained multitudes. I think the one thing we could really say he’d think for sure was, “Anon, follow your own lights, not some media image of a person you never met. Trust yourself.”

I bow to NO MAN when it comes to disliking academic wankery–witness my annoyance with Yoko’s stuff–but I personally thought the idea expressed in your snip very germane. The cover of Pepper does ask the viewer to place The Beatles in the midst of a group of kindred spirits, creative and otherwise, all moving society to something new and better. That’s precisely WHY the LP grabbed people so much in 1967. It was the themesong of a movement, a culture; that’s how people experienced it then. People talked about driving from coast-to-coast and hearing it continuously on FM radio.

So there’s something to Glenn’s inclusion of it, Anon. Ain’t just BS.

Sorry you’re sad, Anon, but something tells me you’re taking it much more seriously than anyone else here.

I think this is very interesting and pertinent, especially for those of us who weren’t around/weren’t of age in the 60s. One reason the Beatles were so big as a cultural phenomenon was that they participated in the kind of utopian dreaming Glenn is tracing through multiple incarnations here.

The “Yellow Submarine” film couldn’t be more explicitly about the Beatles saving a utopian community from destructive forces. (Just as the Beatles themselves were falling apart, of course.)

This kind of dreaming is easy to mock (see the artwork for Zappa’s “We’re Only In It For The Money,” etc.) but the Beatles’ dream is still compelling because they really meant it. And they were more hurt than anyone else when it came apart.

Is there a band or bands today filling a comparable role? I’d be interested in hearing what people think about that.

Mike is better at the kind of broad-based analysis stab Nancy’s question asks for, but I don’t see any bands even thinking in the same terms as the Beatles and their acolytes did in the sixties. It’s a good question what utopia means to anyone now, and to what degree our private utopias include “others” — that is, people with vastly different backgrounds, views, politics, even LOOKS than our own.

The Beatles’ utopia (a very rough word for it) always included, if only implicitly, everyone, even the people who hated them. I spent a good part of “Magic Circles” trying to expound on the unprecedented inclusiveness of their quest, which amounted to a call for engagement and response on a massive scale, whatever form that might take.

Wait till you see Josh’s piece on “Yellow Submarine.”

Speaking of Zappa…I like some of his stuff a lot, but here’s the thing about cynicism: it feels like it’s always appropriate and will protect you from looking foolish; but because it denies the possibility of change, it’s usually proved wrong. So the cynic is just as foolish as the dreamer, and narrow besides.

Imagining something better is always an heroic act; and the reverse is true, too. The utopianism of the hippie movement was, to me, the best thing about it. Surely it’s what makes kids attracted to it today, and when the hippies lost their utopian vision, they became exactly what their enemies said they were. That’s why their enemies acted primarily to dishearten them; CHAOS and Cointelpro were psychological operations, designed to strip away a vision of anything better, and they operated on all fronts. Where the ops ended and mere anarchy took over is a judgment call, but the outlines are clear. Guess when Helms and Angleton started CHAOS? 1967. Guess not everybody thought The Beatles were “Only In It For The Money”…

When people like Zappa–or the Yippies–get frustrated and try to pass themselves off as hard-bitten realists, they invariably get fucked, because they run into people who truly ARE immoral, really don’t care about anything but money, really will exterminate the opposition. To look at the Fabs circa ’67 and see opportunists says more about Zappa than it does the Fabs; and explains why Zappa was, is, and always will be a minor figure. I like him and am glad he passed by–but his inability to break that fetter is significant. It’s not wrong to look at the Hippies and see that wolves can look like sheep; but to assume then that all sheep are actually wolves in disguise is lazy and the opposite of wise.

Zappa, like a lot of cynics, did a lot of ass-whistling about the burden placed upon him by others’ pleasures and pursuits. “Oh, hippies. Oh, disco ducks. Oh, plastic people. What am I going to do with you?”

But I never took his Beatles dig too hard, partly because I never saw it as mean-spirited, and partly because its critique (if you can call it that) of Beatle-exemplified hippieism was too vague and slick to stick. How does a parody of “Lucy in the Sky” imagery demonstrate the Beatles’ mercenary motives? And weren’t the Beatles well past the point where they had to worry about hustling fads to make money?

I think Zappa just used the Beatles as a convenient bullseye when his arrow was truly aimed at the velvety vapidities of hippie culture in general — its style less than its utopian impulse.

By the same token, what makes the Beatles’ utopianism of more than passing interest to me, given my tendency to look on the dark side of things, is the less-than-wholeheartedness of it. Virtually all of their post-Pepper psychedelia is weary, dark, absurd, on the verge of threatening. Though “All You Need is Love” b/w “Baby You’re a Rich Man” is a great single, it won’t take you far down the utopian road if you take the lyrics at face value. If you absorb the performances, though–John’s expressively subdued vocal and the comic bombast of the French national anthem on the former; the mocking falsetto and Mellotron demons of the latter–if you imagine a utopia with this as the soundtrack, it suddenly becomes not only a more fun but a more honest and inventive place than some mind-state of imaginary perfection, free of conflict, ambivalence, or contradictory human desire.

Even utopias gotta have a dark side, and in late ’67, the Beatles were living in it.

I can’t wait to read more pseudo-academic writing!

Maybe the author will tackle this weighty subject…

Paul McCartney and “Band on the Run”: An Argonaut Quest To Write A Song About An Argonaut Quest…

I think Josh is way ahead of you on that, J.R. Keep watching this space.

John No. 37 wasn’t against leftist critical theory, but it wasn’t his language. This is made clear in an interview with Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn in 1971. John tells the two eminent Marxist theorists that he wants to “write songs for the revolution.” I think that was the right choice. Similarly, Tariq Ali can’t lay claim to be one of the finest song writers of the 20th Century.

Anyway, here’s an Argonautic Magic Circle for ya:

Objectivist Ayn Rand had enormous influence on Steve Ditko (comic-book artist and co-creator of Spider-Man and Dr Strange).

Ken Kesey adored Dr Strange and Ditko’s work in general. In 1965 he publicised an early psychedelic ‘Happening’ as “A Tribute to Dr Strange” (a message easily decoded by the right sort of person.) It was a lot less risky than handing out flyers inviting people to an LSD Freak Out Party with trippy lights and weird music.

Kesey, along with Leary, were high-profile LSD evangelists. It’s unlikely that The Freaky Dentist would have spiked John’s drink if Kesey had remained obscure.

And then Paul and George also took some LSD, and they (mainly Paul) made a film that featured a bus that was both magical and mysterious.

SO: we’ve got us a Quasi-Argonautic Day Trip — a jolly holiday that had one foot in objectivist reality (The Mystery Coach Trip was a popular proletarian tradition in 1950s England) and the other foot in yellow-matter-custard, drawn by Ditko and spiked by Kesey’s influence on a somewhat irresponsible dentist.

Love it, greg.

I’ll try agin. Reading this makes my head hurt. Oh well, still loving Mike’s book at least. I love the different character traits you utilize and figuring out who you’re writing about before it becomes obvious. Great stuff.