- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Here’s a welcome sign that Paul McCartney’s solo work is being looked at with new and appreciative eyes: Luca Perasi’s Paul McCartney: Recording Sessions (1969-2013) catalogs all Paul’s solo recording sessions in detail. Well, the first 44 years of his post-Beatles career, anyway.

Among the book’s revelations is just how often McCartney recorded songs he didn’t release for years, or in some cases didn’t release at all. In the course of his researches, Perasi interviewed over seventy people who have worked with Paul over the years, and the perspectives they give on the man and his work are invaluable. Better still, Perasi doesn’t let his obvious affection for McCartney’s solo music keep him from acknowledging its low points. Paul McCartney: Recording Sessions (1969-2013) strikes a good balance between fandom and criticism, and lets the facts play the leading role. This is a book well worth a spot on any Macca-centric bookshelf.

Dullblog’s own Nancy Carr interviewed Perasi via email last week. You can read her questions, and the author’s answers, below.

• • •

HD: In your introduction, you say that the advice Mozart’s father gave him—to write something “short, easy, and popular [because] what is slight can still be great if it’s written in a natural, flowing, and easy style”—captures the essence of Paul McCartney’s music. Can you say more about this? Does it makes sense to compare McCartney to Mozart?

A pop portrait of the people’s Mozart

That sentence from Mozart’s father struck me because he uses the words “short, easy, and popular.” Let’s start with “short”: the pop song format is clearly “short,” since the typical song is around three minutes. “Easy”: certainly McCartney’s music is easy, in the sense that his melodies are instantly recognizable and memorable. The third word is a key one: “popular.” Paul McCartney is the master of popular music.

“Popular” can mean successful, and surely he’s the most successful hit-maker in music history. But “popular” also means a music that has its roots in popular culture and which is juxtaposed to “classical,” as a form of music which requires training to compose.

I think Paul McCartney has elevated popular music to the rank of classical music. He has blended classical and pop musical styles like no other and shows us that, after all, there’s no reason to think of music as “high” or “low.” In his century, Mozart was an artist very like McCartney. He wrote tunes and melodies, and the goal was success. His melodies have endured for centuries simply because they are great. In the same way, I think some of Paul’s songs will be looked at as classics within the next 50-70 years.

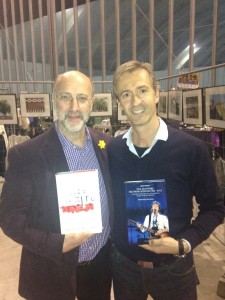

Mark Lewisohn and Luca Perasi display the fruits of their extensive researches at the 27th BeatlesDay in Mons, Belgium (10/11/14).

HD: You did extensive research for this book. What discoveries did you make?

Many people I interviewed for the book had a lot of share — they opened the door to a lot of unknown things. I wanted to discover the exact order of the recordings, and this was not an easy task. Gaps remain, but this is the first book, for instance, that puts the song “I Lie Around” in its right context (the RAM sessions, in the autumn of 1970). For decades everybody thought the track was taped during the Red Rose Speedway sessions, in 1972.

Another discovery was the participation of percussionist Ray Cooper during the recording of “Live and Let Die.”

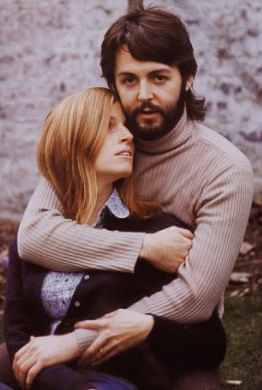

You talk about Linda’s consistent role as McCartney’s “muse.” How do you see her as his inspiration over the years? What do you think enabled him to keep composing music after her death?

Linda represented everything for Paul as a man, and therefore for him as a composer of songs. She was the inspiration behind “Maybe I’m Amazed,” “My Love,” and “Warm and Beautiful,” to name but a few. Her support was essential during the difficult times of the Beatles’ breakup, as we all know, and McCartney acknowledged this.

Linda represented everything for Paul as a man, and therefore for him as a composer of songs. She was the inspiration behind “Maybe I’m Amazed,” “My Love,” and “Warm and Beautiful,” to name but a few. Her support was essential during the difficult times of the Beatles’ breakup, as we all know, and McCartney acknowledged this.

They were so tight. Losing Linda was a nightmare for Paul and I found it extremely touching, and scary too, when he said he was not sure he would be able to survive the pain. Then you open again to life — this is the only thing you can do in these situations. Music is Paul’s work, and you cannot give up doing what you love, regardless of your troubles. You go through your pain and one day you feel better. One day you think that your wife is looking at you from above and she wants you to be happy. That’s all, I think.

HD: Describing McCartney’s denial that “Let Me Roll It” is a conscious imitation of Lennon’s solo style, you say McCartney is either “reluctant to look backward or maybe a skillful dissembler.”

If we browse through McCartney’s interviews over the years, we see that he often changes his stories about a song’s origins or meanings. This has been described as “re-writing history,” but there are a number of things to take into consideration. Human memory can easily fail, and it’s difficult to catalog all the events of your life and the facts about all your songs. For example, he has said two things about the song “Jet”: in 1974 he said it was inspired by a Labrador puppy, which sounded perfectly true, as he explained in detail the story of this puppy. In 2010 he said it was about a pony.

On the other hand, I have the impression that he likes to muddy the waters, for some reason. He adds some mystery to his own legend.

HD: You quote from a number of reviews of McCartney’s work, some of them quite savage (like Rolling Stone predictably calling Back to the Egg a “grab bag of dreck”). What do you think has enabled McCartney to keep going, despite often intense criticism?

Someone said that the difference between successful people and those who fail is that the successful people simply did not give up. Paul’s lesson is: never give up. Despite being a big fan of his solo work, I don’t think everything he did was fantastic or flawless, but [these missteps] are part of everyone’s professional life. Criticism is the other side of the coin when you’re a rock star.

Today, many people think that McCartney has such mythical status that he never faced harsh reviews, which is not true, of course. Quoting period reviews is an important part of the history of his career, and can help us understand what was going on at the time.

HD: You describe the recording sequence of the Fireman’s “Rushes” album, but don’t say much about it. What do you think of it?

Rushes (1998)

Unfortunately, there’s not so much material available about the recording of Rushes, which was the first thing Paul worked on after the death of Linda. The album was recorded only by Paul and Youth and is an experimental work. I like this album, although it is mainly instrumental. The sound textures are interesting and have an ethereal feel, very mysterious and fascinating. I rank it among one of his best experimental works.

HD: You note that people were on the lookout for McCartney to refer to his divorce from Heather Mills on Memory Almost Full — but that he’d already dealt with that relationship on Chaos and Creation in the Backyard without people noticing. Why do you think that went unnoticed?

Very likely, problems with Heather were surfacing not too long after the marriage, probably around late 2004 or early 2005. Paul’s statement about the breakup was made on May 16th, 2006, and we can imagine a time of misunderstanding and problems for the couple. The Chaos and Creation in the Backyard sessions took place during the most difficult period of their relationship, and many songs are quite gloomy, something that is not so typical of McCartney’s style. The whole album is wrapped in a dark mood.

While the lyrics are don’t refer specifically to anyone, songs like “Riding to Vanity Fair,” “At the Mercy,” and “Anyway” express anxiety, delusion, and sadness. McCartney always says he hasn’t someone particular in mind when he writes, but music is the most important means of communication for Paul, and everything in the songs has a meaning — if only perhaps on a subconscious level. It’s too simplistic to see the words as games or casual things. If you’re playing with words, your mind is choosing the words to play with. You choose some words and not others. Most songs on Memory Almost Full were recorded after the separation, and the general feeling of the album is more upbeat. I can see a reference to Mills in “Gratitude,” but McCartney has denied it.

HD: Looking at McCartney’s recent work (Electric Arguments, Kisses on the Bottom, and New), do you see him changing or remaining the same? Does his most recent work stand up to his older work?

McCartney’s essence as an artist is always to change. He is a multifaceted talent: he can cross genres of music like no other. Ballads, vaudeville, reggae, rock, pop, children’s music, soundtracks, big band, orchestral and classical stuff, experimental sounds… I like this aspect of his music.

I must admit I’m not a fan of Kisses on the Bottom however, mainly because it’s an album of covers and McCartney’s strength is as a composer. As a performer of other artists’ material, he’s great when he does rock ‘n’ roll, but McCartney will be remembered in music history for his songwriting skills.

Electric Arguments is a fine album, and I appreciate the fact that the songs are very simple. New is difficult to asses, as it’s so . . . new! Paul admitted last year that he finds it difficult to write songs after 3,000 compositions, and if I’m honest, I think the songwriting on this album is less inspired. The production helps the album sound fresh, but when you emphasize production, you start losing the performance and the real quality of the songs.

I would be curious to hear the New songs in their demo form to better judge the material. The album got good reviews, but I don’t think it makes sense to say that his recent songs are as inspired as the old songs. It’s not true and it can’t be true. After the Beatles, McCartney’s best output is between 1969 and 1973: he was really on fire. “Maybe I’m Amazed,” “My Love,” “Band on the Run,” and “Live and Let Die” (four songs that are still in his live setlist) were all composed between 1969 and 1973.

Everyone has different tastes, and for this reason I inserted only some of my opinions in the book, and gave the leading role to the facts. Personally I consider his early works to be the best: RAM holds first place, with McCartney, Band on the Run, and London Town following. More recent classic albums, in my opinion, are Tug of War and Chaos and Creation in the Backyard.

HD: You call “Maybe I’m Amazed” the “most remarkable song” of McCartney’s solo career. Give us his ten most remarkable solo songs.

I warn you, I could change my mind tomorrow! But I’ll try:

- “Maybe I’m Amazed”: emotional, touching, powerful, raging, with a hair-raising vocal performance. Paul himself is the first to say that “Maybe I’m Amazed” is his most remarkable song, and he stated that he would like to be remembered for this song. I find it touching and powerful: it’s the power that comes when you’re in love.

- “Band on the Run”: a fine example of Paul’s ability as an arranger. He combines catchy pop and hard rock, drawing on varied instrumentation (acoustic guitars, Moog, distorted electric guitar parts, a simple but effective bass part, a big orchestra).

- “Live and Let Die”: a theatrical song. A three-part track, built in such a clever way: it captures the essence of the Bond movie.

- “Another Day”: McCartney in a melancholy mood. Very acute observation of the day-to-day life and struggles of ordinary, lonely people.

- “The Back Seat of My Car”: gorgeous melody and a track combining different registers and parts. It blends influences from Brian Wilson and classical music.

- “Wanderlust”: a rare example of McCartney showing his weakness in the lyrics. Musically, it proves how he masters the rules of harmony, with a brilliant countermelody.

- “Here Today”: another touching song. He deals with the subject of death in a light manner that makes this song a classic.

- “No More Lonely Nights”: one of the best examples of McCartney’s melodic style. It flows so naturally and Gilmour’s guitar adds something special.

- “Little Lamb Dragonfly”: another three-part track in the style of the Beatles’ medleys. Paul deals with his innermost feelings with a gorgeous tune. Gentle, deep and dramatic, this is a song equaled by few in his career.

- “Uncle Albert / Admiral Halsey”: here, Paul blends together countless parts. The “Uncle Albert” part is my favorite, but the whole track is an encyclopedia of styles and musical languages.

Honorable mentions:

- “Somedays”: another gem, this one in the vein of “For No One.” It features a great 18th-century style orchestral arrangement. Touching lyrics, and a memorable vocal performance, nailed in one take.

- “Put It There”: a gentle acoustic song with a light, nostalgic tone. Paul reaches a high level when he puts something personal into his songs, I would like him to do it more often.

HD: What songs do you think McCartney should never have recorded or released?

Tough question. Generally I accept all of his projects, good or bad, but I think he shouldn’t have released Give My Regards to Broad Street. I find the movie quite fun, but I admit that it’s a bit pretentious. The soundtrack is fine, but for the first time in his solo career, Paul turned back to the Beatles consistently. I think this album marks a point where he starts to leave the rock scene as a current artist and begins to look at the past with a nostalgic eye. And I don’t think Kisses on the Bottom is an album he needed to do. His singing is a bit uncomfortable and weak. The whole project sounds insincere to me — unlike, say, Ringo’s Sentimental Journey.

HD: You acknowledge that McCartney has difficulty judging his own work. Why do you think that is?

Judging our own work is difficult, and Paul is no exception. I think it depends on time passing by. For example, look at what he said over the years about the McCartney II album. Back in 1980, he said “synthesizers are amazing things. Instead of spending hours scoring string sections, you can just sit down at this machine and get a very similar sound immediately.” Then, in 1986, he changed his mind: “Listening to it again, I might have done something different: synthesizers are cold and thin, they don’t sound like real instruments sometimes.”

Then, about Venus and Mars, he said at the time that he considered the album stronger than Band on the Run—something he wouldn’t dare to repeat today. He seems a little bit unsure about the quality of his work. We also have to consider the fact that when he releases albums, he’s doing promotion and can’t say of his latest work, “Well folks, it’s not so great, don’t buy it!”

HD: What do you think of the band McCartney tours with, and sometimes records with (Abe Laboriel, Jr., Wix Wickens, Rusty Anderson, and Brian Ray)?

Paul and the boys.

I think they are great as a backing band for live gigs, more than as musicians who can help in the studio from a creative point of view. If we look carefully at the credits for the four albums they were involved in–(Driving Rain [2001], Chaos and Creation in the Backyard [2005], Memory Almost Full [2007], and New [2013])–we’ll find that the only one where their input was really important was Driving Rain. On that album the whole group (except for Wickens; Gabe Dixon was on keyboards), adds their sound to the songs. They appear on only one song on Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, so we can hardly call that a band album.

A similar situation applies to Memory Almost Full. The official credits say the band played on half of it (the tracks were recorded in 2004 at Abbey Road) — but further research shows that McCartney himself re-recorded many parts. Brian Ray said in an interview that his bass parts on this album were later replaced by Paul’s own playing. In some cases McCartney wiped the original backing track, replacing the band’s contribution with is own instrumental parts (e.g. “Feet in the Clouds”).

On New, band members appear on 7 out of 14 songs, and the album has only a couple of tracks on which the whole band performs. I don’t think this band ever developed an original sound, as Wings did. The albums are McCartney albums, with a McCartney sound; end of story. The band works like clockwork on stage, but then they are trying to stay as close as possible to the original, and they don’t need to add any special or different flavor to the songs. McCartney is not Dylan; he does not want to change a single note with respect to the original recordings.

His band members are conscious of their role. It’s not one of giving creative input. But it seems that they have developed a great relationship with Paul and with each other: that’s why they’ve been playing together for twelve years.

HD: You quote some musicians who have worked with McCartney as saying that he doesn’t collaborate; he wants things his own way. Do you think this is true? Do you see his attitude toward collaboration, or his ability to collaborate, changing over time?

Let’s put it this way: Paul McCartney is a genius and has a strong personality. It can be difficult to work with him. He can be very easy, but at times he can have a very different attitude. After over 70 exclusive interviews with his collaborators, I can see that there are two important aspects that never changed over the years.

First, his difference in attitude depends on the role of his collaborators. If he hires, let’s say, a very technical guitarist, it’s very unlikely McCartney would tell him what to do. Let’s remember that McCartney is mainly a composer: as a bassist, guitarist, drummer, and pianist he has fantastic skills, but he’s definitely not a virtuoso. If he hires a guitar virtuoso, there’s no way he’d tell the guitarist what to play. He trusts these musicians. He has to.

When he collaborates with someone who’s classically trained (e.g. a flutist or a cello player for a solo), he likes to challenge him. In this case, his attitude is “You read music, now try to improvise.” He’s asking a classical musician to act more like a jazz player. That’s an interesting way to bring out the best from people. If McCartney works with an arranger, he may suggest modifications and variations, and he’s very interested to hear the sound of an orchestral arrangement. To him the “feeling” may be more important than a perfect performance.

The role of the producer is most difficult; there are many examples in the book of fights and arguments between McCartney and his producers: Hugh Padgham does not have great memories of his collaboration with Paul during the Press to Play album. Even Phil Ramone left the sessions with him back in 1987, because he was not sharing the same approach to the songs. Producer Steve Lipson had a strong argument in the studio with Paul. Nigel Godrich and Paul had a couple of tense moments during the Chaos and Creation in the Backyard sessions (2003-2005).

The aspect of co-writing is somewhat puzzling, if we look back at McCartney’s solo career. After Lennon, he co-wrote songs mainly with three musicians: Denny Laine, Eric Stewart, and Elvis Costello, the last being the only successful example, in my opinion. Denny is a fine musician but is not as prolific a songwriter, as he says himself. The McCartney/Laine collaboration is limited to only eight songs in ten years, with “Mull of Kintyre” being the only hit they wrote together.

In 1985, McCartney wrote the majority of the songs on Press to Play with 10CC’s guitarist and composer, Eric Stewart. Paul admired his work and Eric was a huge Beatles fan. I think this is one of the main reasons this collaboration failed. When two people write songs together, the one thing to do is to be sincere. If a song is not good, you need to say that it’s not good. Otherwise, the collaboration cannot work. Eric admitted that he wasn’t strong enough to tell Paul “No, I’m sorry, this isn’t good.”

Elvis Costello is another story. He definitely told Paul if something was “crap.” I think they came up with some strong material, like “My Brave Face,” “This Day is Done,” or “So Like Candy,” but they could have done more. At a certain point, they disagreed about the production of the songs, and the collaboration fell apart. It would have been very interesting to see a complete album by McCartney and Costello, like Elvis did with Burt Bacharach.

It’s also important to remember that personal feelings often determine whether a collaboration works or not. Everyone has experienced this at one time or another.

HD: How do you think McCartney and his solo work will be judged fifty years from now? Which of his solo works do you think people will still be listening to

McCartney’s solo work has been overlooked and underrated for decades. But that has been partly due to Paul’s mistakes. Starting with the “Paul McCartney World Tour” in 1989-90, the Beatles’ legacy has become more and more important to him. The current setlist limits the solo material to some 1970s hits and the usual four or five songs from the new album. Apart from “Here Today,” there’s not a single song in the set from the 1980s on. But his solo work attracted legions of fans who would pay hundreds of dollars to see him perform Wings tracks live.

Back in 2007, Bob Dylan said “I’m in awe of McCartney,” and he wasn’t referring only to his Beatles years. How can you be in awe of someone if you think he’s done nothing good for forty years? In 2005 Bono told McCartney that all the young bands played Wings songs. In 1999, Bruce Springsteen praised “Silly Love Songs,” and a couple of years ago Elvis Costello chose “Getting Closer” (from the Wings album “Back to the Egg”) as one of his favorite McCartney songs. Things have changed over the years, and we will witness how this material will stand the test of time. Not like the Beatles, but I’m convinced it could be looked at with more interest and reevaluated.

The first important step seems to me to be the release, on November 17th of this year, of the tribute album The Art of McCartney. It features artists like Bob Dylan, Brian Wilson, and Billy Joel. It will present a selection of McCartney’s songs, including Paul’s solo material, and this gives me the feeling that these songs are finally being considered and appreciated. There are a lot of anthem-like songs written by Paul that you can hear at the stadium, during football matches: “Mull of Kintyre” comes to mind. Pop songs like “Goodnight Tonight,” “Coming Up,” or “Ebony and Ivory” are classics.

The first important step seems to me to be the release, on November 17th of this year, of the tribute album The Art of McCartney. It features artists like Bob Dylan, Brian Wilson, and Billy Joel. It will present a selection of McCartney’s songs, including Paul’s solo material, and this gives me the feeling that these songs are finally being considered and appreciated. There are a lot of anthem-like songs written by Paul that you can hear at the stadium, during football matches: “Mull of Kintyre” comes to mind. Pop songs like “Goodnight Tonight,” “Coming Up,” or “Ebony and Ivory” are classics.

Of McCartney’s albums, RAM has acquired a sort of mythical status among some indie musicians during recent years. Band on the Run is still selling. Tug of War contains at least five superb songs. Flowers in the Dirt is a little pop masterpiece.

McCartney’s melodies are timeless and will be reinterpreted by everyone in the decades to come. The catchy songs are the ones that will be remembered — everybody likes to hum a melody in the morning, or when they’re in the car or during a shower. Once Paul said it was a great moment when he heard the milkman whistling “From Me To You.” I think he’s right. This is popular music: music that comes from common people, and returns common people through its success.

• • •

Thx, an informative interview.

I stil wonder why Beatles fans have the artistic work ( in this case of Paul) validated by ‘good’ or ‘not good’ or ‘interesting’or any predictions about future appreciation, by any individual, even it’s the author of a book? Validating a piece of art, even if it’s in the realm of popular music deserves more detail and arguments to inform us.

Macca is coming out loud of the speakers now: Flowers in the Dirt.

Linda wrote the middle part of “Live And Let Die” (“what does it matter to ya, when you got a job to do…” etc.) Her songwriting contributions often go overlooked.

In other news, Stan M. Jay recently died. He owned the Mandolin Bros. musical instrument store on Staten Island. In his ny times obituary, there is a brief description of his experiences with Paul and George:

Paul McCartney did not come personally but sent an assistant to have his Hofner 500/1 violin bass repaired. It was one of two Hofners he had played since the Beatles’ early days. The other had been stolen in 1968, so his assistant was apparently under orders to be vigilant. During the two days of repairs, the assistant watched over the work by day, took the guitar back to his hotel overnight and returned with it the next morning.

“Never took his eyes off it,” Mrs. Jay recalled. “High-strung fellow.”

Mr. McCartney’s testimonial appeared in Bass Player magazine some years later. “My bass never played in tune,” he was quoted as saying, “but I brought it to Mandolin Brothers and they set it straight.”

His fellow Beatle, George Harrison, walked into the store unannounced one afternoon in 1990 and went on a 40-minute shopping spree, buying a very expensive ukulele and a bundle of other things, as Mr. Jay remembered it.

As his wife recalled, “I was just about to take the kids to see ‘Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles,’ ” the movie, “when Stan calls — ‘George Harrison just walked in, get over here,’ ” she said in an interview on Friday. Someone had to watch the store. “Oh, the kids were so disappointed,” she said.

@Sam, that’s my favorite part of the song. Really perfect.

Re: Mandolin Bros. — next time email stuff like that to me, so I can get it up as a post. Happy to.

Great to know about this book, Michael. Thanks!

This interview is fascinating Nancy thanks! I was sorry to come to the end of it. He makes so many interesting points. His comment at the beginning referring to McCartney “elevating pop music to the level of classical” and bridging that gap between so called high and ‘low’ music is the same thing that was said about the Beatles in that excellent ‘Howard Goodall Twentieth Century Greats’ video that Michael posted.

I’m waiting for this book to come out on kindle or for the price to come down. I’ve had my eye on it for a while but it’s a little too pricey at the moment. Do you know anything about it being available on kindle any time soon?

Linda, I asked Luca and he said “an e-book is planned, but no date is available at the moment.”

Linda,

.

We are now about fifty years passed the introduction of The Beatles in America and the year before that they had released already more than thirty songs and performed far more songs on British radio and television. Elitist reviewers were able to comment on their music in musical (not musical as on Broadway) terms and jargon. Even today authors refer to these comments as if that was an important recognition of the quality of Beatles’ music by worthwhile elite music experts that normally dealt with ‘classical’ music.

.

Of course it was not. What do we really know? Is it really a matter of elevated appreciation if a book author suggests McCartney bridged classical music and pop music?

.

Charlie Gillet once suggested in ‘The sound of the City’ the Beatles were “… apparently ready to try any style known to man, contemporary, eastern, 19th century vaudeville… It seemed McCartney would be happy seeing how many different things he could do well… Whatever The Beatles did or drew attention to, inspired a legion of followers.”

.

Jann Wenner wrote in 1968, reviewing the white album:

“one of the ideas of the LP is to contain every part of extant Western music through the all-embracing medium of rock and roll…

“Sgt. Pepper’s applied the concept of the symphony to rock and roll, adding an incredible (and soon overused) dimension to rock and roll. Nothing could have been more ambitious than the current release: The Beatles in the history and synthesis of Western music.

“…the Beatles can safely afford to be eclectic, deliberately borrowing and accepting any outside influences or idea or emotion, because their own musical ability and personal / spiritual / artistic identity is so strong that they make it uniquely theirs, and uniquely the Beatles. They are so good that they not only expand the idiom, but they are also able to penetrate it and take it further.

“…Part of the phenomenal talent of the Beatles is their ability to compose music that by itself carries the same message and mood as the lyrics. The lyrics and the music not only say the same thing, but are also perfectly complementary. This comes also with the realization that rock and roll is music, not literature, and that the music is the most important aspect of it.”

.

It is this quality of their art that makes it equal to the best music from the centuries that went before and that probably includes the best, including ‘classical’ music.

.

Let’s continue to read Wenner:

“…Part of the success of the Beatles is their ability to make everything they do understandable and acceptable to all listeners. One needn’t have an expert acquaintance to dig what they are doing and what they are saying…

““Honey Pie” is … one of those perfect Paul McCartney evocations of a whole musical era, understanding the essence so finely, that it could be as good as the original. Lovin’ the rhymes: crazy-lazy, tragic-magic, frantic-Atlantic. He not only is able to re-create such moods and eras with his melody, his words, his arrangements, instrumentations, but also with his voice. He is equally expert in all these areas.

“He (Paul) uses every available musical device and cliché available, melodies, instrumentations, arrangements, harmonies, everything, and he does something entirely professional. … neither Paul’s near-genius ability with notes nor John’s rock and rolling edge of honesty are sine qua non for the Beatles. The taste and sense of rightness in their music, to choose the perfect musical setting, the absolutely right instrument, are just as important.”

.

It is already a long time ago that not just The Beatles were acknowledged as creative very skilled musicians… What’s new Now? The time that the best of popular art is considered ‘merely’ low art, is long long long gone gone gone.

.

We still have a problem of not really understanding or having agreement of what constitutes art – or a piece of art. Of course we look at art with the perception that it is a distinct item, a thing, a painting, a piece of music, an opera, there should be at least a beginning and an end to it. A drawing John can be art, but are album cover designs art? Is the stage design of U2’s Zooropa tour art, I think it is high ART.

.

However is it relevant? I wonder why, what is it about that need for acknowledgement? Is it the Calimero syndrome or the desire of Beatles’ fans to feel acknowledged in the quality of their judgment of art? We are not just in love with a boys band and their music – their must be more to it.

.

I dunno what credibility Luca Perasi has that adds importance, plausability and probability to his statements about art and classical music, and Paul having build bridges between pop and classical music.

.

The questions, hesitation and suspicion I have with this old fashioned ‘high’ vs ‘low’ art competition comes partly from having lived thru the seventies and the pop art in my house, today and having read ‘Revolt Into Style’ by George Melly. Really the matter is really not a relevant issue.

.

.

Now maybe we can approach the problem from the other side, what. Is classical music, and is Mozart the pinnacle, is Mozart today or in the past essentially classical music? For one, I prefer modern ’classical’ music from Berg, Weber, Olivier Messiaen, Sofia Goebaidulina, Henryk Gorecki, Mauricio Kagel, Galina Oestvolskaja, Claude Vivier, Klaas de Vries, Gyorgy Ligeti, Stockhausen and Louis Andriessen. Even better still, is the ‘real thing’: to go to concerts where music from living composers is performed.

.

What is classical music? Below a few paragraphs from an article that just appeared on line at the New Yorker, which explains where and when the concept of ‘classical music’ and the way we listen to it today originated from.

.

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/10/20/deus-ex-musica

.

Beginning of quote…

“Beethoven is a singularity in the history of art—a phenomenon of dazzling and disconcerting force. He not only left his mark on all subsequent composers but also molded entire institutions. The professional orchestra arose, in large measure, as a vehicle for the incessant performance of Beethoven’s symphonies. The art of conducting emerged in his wake. The modern piano bears the imprint of his demand for a more resonant and flexible instrument. Recording technology evolved with Beethoven in mind: the first commercial 33⅓ r.p.m. LP, in 1931, contained the Fifth Symphony, and the duration of first-generation compact disks was fixed at seventy-five minutes so that the Ninth Symphony could unfurl without interruption.

.

After Beethoven, the concert hall came to be seen not as a venue for diverse, meandering entertainments but as an austere memorial to artistic majesty. Listening underwent a fundamental change. To follow Beethoven’s dense, driving narratives, one had to lean forward and pay close attention. The musicians’ platform became the stage of an invisible drama, the temple of a sonic revelation. Above all, Beethoven shaped the identity of what came to be known as classical music.

.

In the course of the nineteenth century, dead composers began to crowd out the living on concert programs, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center. As the scholar William Weber has established, this fetishizing of the past can be tracked with mathematical precision, as a rising line on a graph: in Leipzig, the percentage of works by deceased composers went from eleven per cent in 1782 to seventy-six per cent in 1870. Weber sees an 1807 Leipzig performance of Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the titanic, turbulent “Eroica,” as a turning point: the work was brought back a week later, “by demand,” taking a place of honor at the end of the program. Likewise, a critic wrote of the Second Symphony, “It demands to be played again, and yet again, by even the most accomplished orchestra.” More than anything, it was the mesmerizing intricacy of Beethoven’s constructions—his way of building large structures from the obsessive development of curt motifs—that made the repertory culture of classical music possible.”

End of quote.

.

Not Haydn, nor Bach let alone Mozart created the concept of classical music that today finds it pinnacle in the Dutch Concertgebouw and Vienna’s Konzerthaus and the symphony orchestra’s performing romantic music, called ‘classical music’.

.

Just for some closure, is the comparison of Macca’s music with that of Mozart a compliment?

.

“I wish I could hear the beauty of Mozart’s music as new and strange, but it often seems to be hidden from me by a veil of familiarity which I lack the musical insight to penetrate. In the world I have lived in, Mozart’s music has been taken for granted, smoothed out through constant repetition, skilfully packaged as a cultural commodity, casually churned out at ‘Mostly Mozart’ marathons in New York and London, reduced to background music for the annual passeggiata of the Euronouveaux riches at the Salzburg Festival. Performances of Mozart are now rites rather than occasions for discovery. It is incumbent on us to say we love Mozart.”

http://www.lrb.co.uk/v17/n24/nicholas-spice/music-lessons

.

Sorry for my not so native english, I’m from Europe.

Part of the phenomenal talent of the Beatles is their ability to compose music that by itself carries the same message and mood as the lyrics. The lyrics and the music not only say the same thing, but are also perfectly complementary. This comes also with the realization that rock and roll is music, not literature, and that the music is the most important aspect of it.”

@Rob your English is fine no apology needed and the above comment is the Beatles in a nut shell. I’ve always wondered why so many people don’t understand that pop music is not literature, even great pop music with great lyrics. The music is the important part. It’s not a poem, it’s a piece of music.

Thanks for the Wenner quotes. They are new to me and very interesting.

@Nancy, Thank you for checking on the kindle book. I hope it comes out soon, or I might break down and just spring for bound version.

The Jann Wenner quotes are from his review of the White album, I found it among many other reviews of the double album on the website ‘The White Album project’ – http://www.thewhitealbumproject.com/reviews/rolling-stone/

B.t.w. I was not surprised by Wenner’s nasty remarks about people who did not have an understanding of The Beatles’ music he endorses, quite a narcisist way to go. It is sad to see him provide a comment to the album that shows he has a way with words but is more fan-like than substantial. It reminds me off his correctional move towards Greil Marcus when the latter had a dismissive review of McCartney’s first solo album in 1970.

Rob, Jann Wenner actually pressured Greil Marcus to make the review of McCartney’s first solo album more negative. Marcus was records review editor for the magazine at the time, and in an interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books he explained what happened:

You can read the interview here.

And Hey Dullblog comments on it here.

Wenner’s a Beatles fan, but when the band broke up he sided with Lennon. The magazine’s review of “Ram,” written by Jon Landau, has become infamous over the years for its savagery.

I don’t think humans will ever agree on how to define or evaluate art, any more than we’ll agree about the meaning of life. But it’s through discussion that we come to a better understanding of what we think and of why others see things differently. Sometimes we may even change our minds–that’s my experience, anyway.

@Nancy, I’m sure I said this in the comments, but that’s actually an example of really BAD editing — the owner and boss of a publication allowing his personal taste to put forward an agenda under someone else’s name (Langdon’s and/or Marcus’). That Greil Marcus STILL doesn’t see this makes me deeply skeptical of him, both as a journalist and a writer.