- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

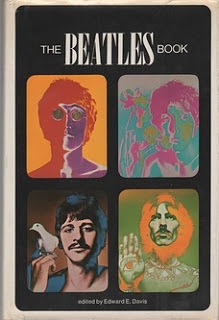

NANCY CARR * William F. Buckley really hated the Beatles’ music. I’d known this in a general way, but hadn’t read his diatribes against them before encountering them in The Beatles Book, a 1968 anthology of critical writing about the band edited by Edward E. Davis. (Finding books like this makes me feel justified in spending what is probably way too much time in used bookstores.)

Buckley’s 1964 National Review article on the Beatles was entitled “Yeah, Yeah, Yeah, They Stink.” He piles on the adjectives in an effort to convey his absolute loathing of their sound:

“Let me say it, as evidence of my final measure of devotion to the truth: The Beatles are not merely awful, I would consider it sacrilegious to say anything less than that they are godawful. They are so unbelievably horrible, so appalling unmusical, so dogmatically insensitive to the magic of the art they qualify as crowned heads of anti-music, even as the imposter popes went down in history as “anti-popes.” It helps a little bit to know that no one thinks they are more of a joke than the Beatles themselves, and one is relieved in supposing that they go to bed at night laughing at their utterly inexplicable success, if solemn at the thought that they must inhabit a world that features themselves.”

As someone who practically goes into anaphylactic shock when exposed to the Beatles’ music, Buckley struggles to understand how that music has become so popular. He describes a taste for the Beatles as as “a lamentable and organic imbalance,” and speculates about how it has developed:

“If our children can listen avariciously to the Beatles, it must be because through our genes we transmitted to them a tendency to some disorder of the kind. What was our sin? Was it our devotion to Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Ella Fitzgerald? How could that be? We worshiped at the shrine of Purity. What then, gods and goddesses, was our sin, the harvest we are now reaping? We may not know what it was, even as Oedipus did not know during all those years the reason why he was cursed.”

This is at least a little tongue-in-check, with its hint that being an avid Sinatra, Garland, or Fitzgerald hardly qualifies as worshipping at the shrine of Purity. The reference to Oedipus’ curse is consciously over the top. But the inability to understand a liking for the Beatles’ music—the inability to hear the Beatles’ music AS music—is absolute and unironic.

Then, in 1966, Buckley wrote about Lennon’s comment that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” Buckley’s response is actually more rational than that of many who wrote about the comment:

“Reaction to his statement appeared to be based on the assumption that Mr. Lennon was comparing not the relative popularity of himself and Jesus, but their related virtues. And this is, of course, to miscomprehend what Mr. Lennon said, which was certainly untactful and indubitably accurate . . . . Mr. Lennon’s rather course ejaculation was to be sure the plain truth, hardly shocking to students of the Bible, who know the relative attractions of Mammon over God.”

That’s fair enough, and bracingly said.

Much as Buckley hated the Beatles’ music, in 1968 he did acknowledge that “even if the Beatles are hard to listen to, there is an exuberance there that is quite unmatched anywhere else in the world.”

I’m dumbfounded by Buckley’s insistence that the Beatles are unmusical, but I’m grateful for the historical perspective it affords. His reaction is a reminder of how revolutionary the Beatles sounded even in 1964, when they were singing “Please Please Me,” “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

Here’s a link to a Wall Street Journal piece on people who hated the Beatles. Buckley, of course, makes an appearance.

Yet another reason to loathe William F. Buckley. I hold him in particular disdain because I know so many people of precisely that background (wealthy, Eastern Yale grads from the 1950s) who were/are decent, thoughtful, politically flexible and genuinely compassionate. Buckley was none of these things, a small character who dressed up his fear with preppy totems, Latinate words and a ridiculous accent of his own invention. His obit in the Yale Alumni Magazine made me nauseous; it was a catalogue of all the foolish, mean things he said and did, invariably playing to people’s narrow tribalism and sense of threat–chirpily counterbalanced by tales of his personal politeness. A bully who writes thank you notes is still a bully.

But politeness is something, I guess. Someone once called Newt Gingrich “what stupid people think smart people are like,” and that goes double for Buckley. The stylistic differences between Buckley and Gingrich nicely sum up the changes (I’d say decay) in our public culture between 1960 and today.

That Buckley could not hear The Beatles as music speaks volumes; why should that bit of reality escape his peculiar neurosis? Buckley knew The Beatles were the enemy from the moment he saw them, and he was right.

The fact that he was unable to articulate his criticism properly and resorted to diatribe speaks volumes about his motivation and understanding.

Sometimes it’s affirming to find certain individuals in the opposite camp to yourself.

As you say, Nancy, it reminds me again that “She Loves You” was revolutionary, which is easy to forget. (For me.). As I read the diatribe, I kept thinking, “Could the Beatles have sounded that different to Buckley from Elvis or the Crickets?” And I realized (was reminded) that, yes, they did. Their sound was grittier and/or their voices less polished than most pop acts that came before them. And they presented it all with those shit-eating grins that seem to have haunted Buckley’s nightmares. His negativity reminded me of some of the reasons I love their early act. Thanks, Bill!

Don’t forget that Buckley was a current-events commentator, and a current-events commentator’s primary job is to fill empty space with words. I will dare to suggest that Buckley’s judgement of the Beatles was insincere: that he was feigning outrage in order to complete a column. In 1964, it was thinkable that the Beatles would soon disappear without a trace, and a diatribe against them would subsequently seem an act of exceptional insight rather than total lack of imagination. I don’t dispute Michael Gerber’s characterization of Buckley’s faults; I just think that in this instance, Buckley consciously chose to adopt a pose of indignity to write a humorous and, he believed, prescient column. As it turned out, he bet on the wrong horse.

@Mudarra, while I see your point as far as it goes, I think you’re missing something essential about Buckley and ilk by calling him a “current-events commentator.” WFB did not merely wish to comment, he meant to drive and shape events. When he said The Beatles stank, he wanted people not to listen to them, and characterized them harshly to underscore the point. But making them hustlers laughing all the way to the bank reflects Buckley’s morals, not theirs. This is what I meant by a small character.

As Buckley seemed to mellow with age–or realize that American rightwingers were increasingly insane–it became common to assign a certain avuncularity to him. This is too convenient. In the Sixties, WFB was in full crusader mode; and it’s precisely that true-believer blindness that made him misjudge The Beatles so badly. Not that he ever lost a wink of sleep over it; Buckley was only interested in The Beatles insofar as he could use them to polemicize. Perhaps he was only interested in anything to the precise degree it helped or hindered his peculiar desire to “correct” modern life. The Beatles HAD to stink because WFB saw them as on the other side of the class-and-culture war he was waging, not because he had column inches to fill. Then he uses Lennon’s Christ comment to underline the moral decay of the modern age, presumably fixed by everyone listening to Bach, going to Mass, and installing a governing aristocracy.

Such desires are adolescent even when they are harmless, and in Buckley’s case they were not, because he did everything he could to make his obsessions our reality. (Always a bad idea.) In WFB’s case it’s hubristic AND ignorant: one needn’t read very much history to discover that full or even partial realization of Buckley’s fetishes would not lead to us to Utopia.

I don’t deny the guy had a certain wit and charm; and I actually share many of his affections. But he made an entire career out of appealing to the paranoid wing of American conservatism; if he eventually realized the error of this–as when he eventually realized that Martin Luther King et al were the good guys, or that American military adventurism is a terrible idea–it’s only fair to remember that there were a lot of people on the RIGHT side of that from the beginning. (The Beatles, for one.)

To the degree Buckley and his magazine can claim some paternity for the modern American Right, he has much to answer for. William F could’ve had his son’s career, hurt no one and amused many–while putting forth certain political opinions. But he chose to shape events, and thus must be judged by sterner standards.

Good points, Michael. You’re right, Buckley was something more insidious, and his hatred of the Beatles reflected a deep, activist (not in a good way) agenda.

I was eleven years old when the Beatles hit, and listening to their music was like having joy forced into my brain through my ears. But my parents, who were rational, decent people, were indifferent to them. So I think that the capacity to respond to new types of music may be a gift of youth, which then fades over time. I’m an old man now, but somewhere in my thirties I lost interest in listening to the radio, because there was nothing there in the new popular musicians to attract me.

So I’m sure that, while Buckley didn’t like the Beatles, his professed loathing for them was a pose. Buckley was a pompous phoney. There was a novel called The Little Drummer Girl by John LeCarre, and Buckley wrote a review of it. Anyone who has read the book will notice that Buckley had only read the first chapter, and then cribbed the substance of his review from other reviews. The reason this is obvious is that a character introduced in the first chapter is revealed in the second chapter to have been using a false name in the first chapter, but Buckley’s review refers to the character by the false name instead of the real one, because he hadn’t read enough of the book to learn the character’s real name.

Gore Vidal, who famously debated Buckley, remarked on Buckley’s lazy refusal to research any question. He just got the general gist of an issue and padded it out with orotund prose. That was his style. So back to his review of the Beatles, it is my guess that he hadn’t really listened to the Beatles for more than a few minutes, and was just making a big show of how much he disliked them as a kind of cultural posturing. That was Buckley, who had no real integrity as anyone might recognize that term.

In reading Buckley, it is impossible to sort out his real opinions from the ones he is just pretending to hold for the sake of whatever argument he wants to make. For example, Buckley claimed to be a believing Christian. It is impossible for an educated man to actually believe the the Christian Gospels are literally true, and that Jesus of Nazareth rose from the dead. People who say they believe this (hello, C.S. Lewis and G.K. Chesterton) are just having us on. Christian belief for most professed Christians is just a cultural marker, and people use it to announce their membership in that particular club. Everybody did this in the fifties, but virtually nobody tries that on today. When was the last time you heard a public figure (who was not a rap musician with an I.Q. of 85) announce a belief in Jesus Christ?

So Buckley was a poseur. He probably didn’t care about the Beatles, but he understood that it was a badge of honour in his circle to despise them, so he just cooked up one of his little, show-off goon squawks decrying them. I really don’t see Buckley listening to popular radio, and he probably would have considered it beneath him to watch the Sullivan Show. He just didn’t know anything more about the Beatles than he’d read in Time Magazine.

а

Wow, calling them “unmusical” is a bit harsh! I have to admit that when I first heard the Beatles, all I heard was their early work, and I wasn’t very impressed. They sounded like every other band of that time period, to me. It was their later work (Rubber Soul, and especially Revolver, and on) that really impressed me. That being said, I would never call the Beatles “unmusical”–for a band that can produce catchy tunes and decent melodies, how is that even possible? Part of me wants to think Buckley was being a bit sarcastic. How can anybody be that upset over a band? I can’t say I know much about Buckley, but his response seems a bit over-the-top, to me.

I think Buckley was afraid of what the Beatles represented: a powerful youth culture that was arrayed against the kind of conservatism he championed. He saw which way the wind was blowing, and he didn’t like it. Also, to people used to the likes of Pat Boone, the Beatles may well have sounded “unmusical” because their style was so unfamiliar. Consider that Ed Sullivan apparently referred to some of Buddy Holly’s music as “raucous.”

The Beatles represented a lot of very threatening things to conservatives who, then as now, were over the top in their rhetoric. I would be inclined to take Buckley, a person who cared about language, at his word.