- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

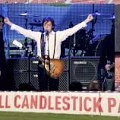

NANCY CARR • Who can open a sold-out arena show with two songs he worked on that were released nearly 50 years apart? That would be Paul McCartney, who started his August 14 Candlestick Park concert with “Eight Days A Week” (1964) and “Save Us” (2013). McCartney closed down Candlestick in a rain of firework sparks and confetti, after playing 40 songs that often had the crowd singing, clapping, and dancing along. At this point it can be easy to take his shows for granted: you know certain songs will be played, that Roman candles will be set off during “Live and Let Die,” that McCartney’s one, wryly announced “costume change” consists of taking off his jacket and rolling up his sleeves. But the quality of the music, his still-formidable performance chops, and most of all the energetic glee he takes in playing live, make a McCartney show an experience like nothing else.

At 72, McCartney well knows “I go back so far I’m in front of me.” How does he not only live with, but go on presenting himself as a public figure with, such a well-known and and often contested past? After seeing this show, I’m convinced he does it by performing the past. Doing so, he brings it into the present and acknowledges it as past. In every show, McCartney invokes yesterday and tries to work out how to live with it today.

McCartney’s Ever Present Past

These days his concert setlist includes many Beatles songs that the Beatles never did for an audience. It’s as if during those non-touring years he built up a head of performance steam that he’s still releasing. He played 16 Beatles songs released after the band stopped touring, including “Paperback Writer,” “All Together Now,” “Lovely Rita,” “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da” “Golden Slumbers,” “Carry That Weight,” and “The End.” He also highlighted which of his post-Beatles songs he did with Wings, even putting up the Wings hand sign a couple of times.

Throughout, McCartney was never still, switching from bass to guitar to piano and back, rocking on his Cuban-heeled boots while singing, even turning his back and shaking his butt for the camera. It’s a knowing performance that includes a sharp recognition of what people want to see, but he seems to offer it freely and without resentment. It’s what the audience wants, but hey, it appears to be what he wants too.

Just because the show was so good—McCartney in surprisingly fine voice, his playing and the band’s consistently excellent—I chafed at its limitations. I wished McCartney had drawn more on the last three decades of his solo work. Apart from “Here Today,” released in 1982, everything was from the sixties, the seventies, or his most recent two albums. I may be an outlier in this respect, but I’d have happily dropped a few of the Beatles tunes to hear McCartney do something like “My Brave Face,” “The Songs We Were Singing,” “Run Devil Run,” “Fine Line,” or “Ever Present Past.”

And I wanted him to tell more different stories, more different jokes, to be more unpredictable generally. Why stay with the same thing, when he must know—mustn’t he?—that the audience would go willingly with him.

Juggling Public Performance and Private Emotion

But McCartney won’t—or, I think more accurately, can’t—give us that kind of unpredictability. That he gave us two and a half hours of great music, while appearing to enjoy being there as much as anyone in the audience, will have to be enough. Increasingly I think that the elements of sameness are a form of protection, a way of staving off the past’s power when it might overwhelm him. Most obviously, the anecdotes about John Lennon and George Harrison seem to make it possible for McCartney to acknowledge their deaths in a way that feels safe in front of tens of thousands of people. He’s willing to open himself publicly, but only so far, and he’s determined in advance exactly how far that is. I think the parts of the show’s structure that don’t change make him feel secure enough to keep performing, because they reassure him that he’s not giving away too much of his private self.

Thus McCartney introduced “Here Today” as he always has, as a conversation between him and John Lennon “that we never got to have.” But the song itself sounded rawer emotionally than the recorded version, perhaps because of the limitations of McCartney’s aging voice. The entire audience was silent as we watched McCartney, standing alone on a raised platform that had a flowing waterfall projected on it, sing this song so clearly born from pain and regret. Trying to stand on moving water, I thought—that’s what being Paul McCartney, perennial ex-Beatle, must feel like sometimes. Whether you interpret that waterfall as the inexorable passage of time or as “water under the bridge,” standing on it renders instability visible. No wonder he feels he can’t let his guard down too far.

Thus McCartney introduced “Here Today” as he always has, as a conversation between him and John Lennon “that we never got to have.” But the song itself sounded rawer emotionally than the recorded version, perhaps because of the limitations of McCartney’s aging voice. The entire audience was silent as we watched McCartney, standing alone on a raised platform that had a flowing waterfall projected on it, sing this song so clearly born from pain and regret. Trying to stand on moving water, I thought—that’s what being Paul McCartney, perennial ex-Beatle, must feel like sometimes. Whether you interpret that waterfall as the inexorable passage of time or as “water under the bridge,” standing on it renders instability visible. No wonder he feels he can’t let his guard down too far.

McCartney’s secret

My favorite moment of the evening came during the second encore, when McCartney said he would do “the last song we played at Candlestick.” He proceeded to bust out “Long Tall Sally,” a daring move for a septuagenarian. As he sang fresh energy seemed to  crackle from him, and he looked lost in song, all guardedness forgotten. Behind him scenes from the Beatles’ 1966 Candlestick show were being projected. And as I looked simultaneously at an image of the young McCartney performing and at the veteran onstage, I felt the tumblers of a combination lock clicking into place, allowing the door to swing open and show us all McCartney’s secret: at the deepest possible level, deeper than the hype or the occasionally gratingly ingratiating public persona, lies a man forever enraptured by playing and sharing music. Now as then, he’s getting a genuine kick out of his gift and seeing people love what he does with it.

crackle from him, and he looked lost in song, all guardedness forgotten. Behind him scenes from the Beatles’ 1966 Candlestick show were being projected. And as I looked simultaneously at an image of the young McCartney performing and at the veteran onstage, I felt the tumblers of a combination lock clicking into place, allowing the door to swing open and show us all McCartney’s secret: at the deepest possible level, deeper than the hype or the occasionally gratingly ingratiating public persona, lies a man forever enraptured by playing and sharing music. Now as then, he’s getting a genuine kick out of his gift and seeing people love what he does with it.

I carried the memory of that moment away with me. It could not be tarnished even by the unbelievably tortuous journey out of the stadium and then the parking lot (if someone had set up the concert to show why the only reasonable thing to do with Candlestick Park was tear it down already, they would have proved their case many times over). It still seems unbelievable to me that I, just a few weeks old when the Beatles played Candlestick, got to see Paul McCartney shut the place down with such undimmed verve and joy.

Nancy, have you read “Man on the Run,” the recently published book of interviews with McCartney? The pages I read in the Amazon preview look really interesting. The interviewer is quite open about how difficult it is to break down PM’s resistance to spontaneity. He writes that while PM can be quite predictable in his non-answers, other times he will “kill himself laughing” as he chats on the phone while driving behind a tour bus in Los Angeles, or go off on a great swearing streak when asked about his “thumbs up, happy chappy” persona.

Ingrid, watch this space! Michael and I have both read it, and sent questions to Tom Doyle, hoping for an interview. But we, or at least one of us, may well end up reviewing it.

I agree with you about the “thumbs aloft” section of Doyle’s book: I got the feeling that McCartney not only hides behind that persona in public often, but that he hides from himself that that’s what he’s doing. More anon . . .

Contact made, questions sent…we’ll see what happens next!

Exclusive: Paul & Johnny Depp:

.

http://www.esquire.com/blogs/culture/premiere-paul-mccartney-early-days?click=feed

.

Earlier this summer Paul McCartney released a video for his song “Early Days” which featured him playing with a roomful of blues musicians and Johnny Depp.

Reading about it made me miss him so much. I have just seen him in concert too, for the first time. And I miss him! It was very much like you said. But he started the show singing “Magical Mistery Tour” which I think it was even better than “8 days a Week”. It was an invitation to roll up…And we all entered in a magical world. Another difference is he didn’t explain anything about “Here Today”. Only it was for John. And of course you didn’t have the chance to listen to him speaking in Portuguese. Delightfull. We Brazilians loved every second. Paul is indeed carrying the Beatles torch.

[…] on the Beatles, as well as on a wide range of other musicians and performers through the decades. I wrote about seeing Paul McCartney perform “Long Tall Sally” at Candlestick park back in 2014, and that […]