- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

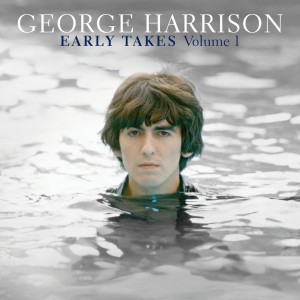

DEVIN McKINNEY • Note: These are not new impressions, but ones jotted down in May 2012, the day Early Takes: Volume 1 came in the mail, and embellished more recently.

DEVIN McKINNEY • Note: These are not new impressions, but ones jotted down in May 2012, the day Early Takes: Volume 1 came in the mail, and embellished more recently.

George, in a photo taken in a Bahamian pool during the filming of Help!, holds his head above the water’s crystal surface, his face the perfect expression of the solemn young seeker braving the eddies and tidepools of the material world: a Siddhartha for the ‘60s. The image is rich, quiet, suggestive, like George at his best.

It’s beautiful wrapping on a gift that isn’t quite there. Olivia Harrison, Giles Martin, and whomever else was involved have made this a tender little release, but behind the front cover Early Takes: Volume 1 holds little in the way of context, data, or style. It needs more imagination, in all aspects of its presentation—titling, annotation, programming. Modest to a fault, the album is barely over a half-hour long, with a number of songs which, due to their tentative, exploratory nature, do not resolve in worked-out endings but simply stumble to stopping points before dissolving behind giggles and talk. There’s no sense that the selections have been sequenced in a particular order for ebb and flow, startling starts or dramatic culminations. Granted, it’s a collection of demos, sketches, and, indeed, “early takes”; but those who assembled it were hardly obliged to make the album sound like an early take of itself.

It’s to my surprise, I will say, that few of the tracks are among those which have been commonly available on bootlegs for well over a decade—chiefly, but not only, Beware of ABKCO! and Songs for Patti, both released in 1994 on the Strawberry label. Nor are most of these tracks found even on the five-disc The Art of Dying: The Complete All Things Must Pass Demos, Sessions and Remixes. But astonishingly for a collection devoted to a man who spent so much of his life in the proud community of session players, the liner offers no information on accompanying musicians or recording dates. That’s all given, no doubt, with the deluxe DVD, but it’s a real skimp not to provide it here: I paid my $12—give me the names.

Track by track:

1. “My Sweet Lord.” Previously unheard by me, this is listed as a demo, though an engineer slates it “Take 1,” and George’s ill-tuned acoustic guitar is accompanied by drums, presumably Ringo’s, and bass, presumably Klaus Voormann’s. The run-through is ragged, sketchy, the merest shadow of the resultant glory.

2. “Run of the Mill (Demo).” Again slated as Take 1. George solos on acoustic. This is the same demo that’s found on ABKCO! and Patti.

3. “I’d Have You Any Time [sic] (Early Take).” Such a gorgeous song. This full-band version of the Harrison-Dylan composition, very similar to the released take, features some bum notes from Clapton, but it has a charging, forceful quality on the refrain that the LP version lacks. Includes a count-in, for what it’s worth. (A lot: I love count-ins.)

4. “Mama You’ve Been on My Mind (Demo).” Another previously unheard outtake. George’s execution of one of Bob Dylan’s most affecting early ballads is expectedly sweet, with some haunting instrument (what instrument?) tootling in the background. Sounding quite finished for a demo, it could have been released commercially—though clearly it would have violated the Wagnerian gestalt of All Things Must Pass.

5. “Let it Be Me (Demo).” Another pretty, unbootlegged cover version, this time of the Everlys, with some trademark Harrison guitar flourishes. (Who is the harmony vocalist? George O’Hara Smith? Drat the lack of info!) This too sounds well beyond the demo stage. Note that Dylan included a terrible version of the same song on his Self-Portrait album, released back at the beginning of 1970.

6. “Woman Don’t You Cry for Me (Early Take).” The Dylan theme continues; clearly George, unlike John, believes in Zimmerman. This is a 1963-reminiscent folkie thing whose chief pleasures are a nice acrobatic vocal and some tricky folk guitar—we don’t often hear George working out on acoustic this way. Someone pops a Jew’s harp to the rear. (Who?!?)

7. “Awaiting on You All (Early Take).” A small-band fuzz-funk version of the enjoyably bombastic, traffic-jam album version. [Mis]announced by George as “Awaiting for You All.” Previously unheard.

8. “Behind That Locked Door (Demo).” George flies solo, until a steel guitar (Pete Drake?) unexpectedly steals in for a lovely liquid interlude, to lift yet another of these “early takes” past demo status. Refreshing, and quite lovely in its simplicity; might be superior to the album version. Previously unheard.

9. “All Things Must Pass (Demo).” Acoustic guitar, bass, drums, and a little dull. Lacking the focused, fixated quality of the one-man, one-guitar Anthology 3 demo, it stutters to a premature close.

10. “The Light That Lighted the World (Demo).” Prettily done, but a weak closer. The only song to come from Living in the Material World, and probably meant as a teaser-pointer to Volume 2.

In all, Early Takes: Volume 1 is a fine collection that rates with the better All Things-era bootlegs. The preponderance of unbooted material lends it value and novelty, but the complete presentation, as noted, is lacking in almost every department. From a bootlegger, such deficiencies would be excusable; from intimates and insiders with unfettered access to the Harrison vaults, they are unaccountable.

Perhaps this is a kind of placeholder release, designed, in the fashion of operating systems or refrigerators, to be superseded somewhere down the line—perhaps by a time-spanning, multi-volume outtakes collection loaded with the meat and potatoes of information and the garnish of graphic design. But if that’s the plan, it’s a foolish one. Each segment of a staggered release ought to wear its own colors, have its own personality, be a satisfying immersion in its own piece of time. Each of the Beatles Anthology CD installments was awesome on its own, while still fitting into a clear overall design. Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series—whose Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (1969–1971), released last August, included a number of Dylan-Harrison collaborations from the Early Takes era—is a model of how such releases should be done; yet another is Neil Young’s mammoth ongoing Archives series.

But on second thought, forget the “placeholder” theory. I think the more likely, and even more perplexing, explanation is that no one in the Harrison orbit saw Early Takes: Volume 1 as a particularly important release—that it was felt to be, at best, an appendage to the Living in the Material World documentary, with cultural muscle for both coming courtesy of Martin Scorsese and HBO, more than George himself. But the man and his songs deserved better than this near-nonentity of a collection, which is, after all—aside from the bonus track-rich thirtieth-anniversary edition of All Things Must Pass—the first official issue of unheard Harrison material.

Postscript: Which, as of January 1, 2014, it remains. Where’s Volume 2? Google is so far mum on the subject.

@Devin, you’ve convinced me to get this disc–I listen to my digipak “Beware of ABKCO!” all the time, but this release got lost in the publicity wash of the Scorsese doc. I am easily distracted, even on favorite topics.

What I love about the cover is that George appears to be standing in the pool fully clothed—very much his sense of humor.

The bare presentation of this brings to mind a point I thought of last night: one of the reasons that George isn’t as fascinating (or at least talked about) as John and Paul is that, unlike John and Paul, he simply wasn’t as generous to his fans. Not with his time, or his material, or his neuroses, or anything. To colleagues and friends he seems to have been uncommonly generous—but to admiring strangers, he was dismissive to disdainful. This isn’t just a tendency, it’s a strategy designed to keep one’s identity firm in the face of lots of unreality.

I suspect that the interface with the estate quickly became bounded by “what George would’ve wanted”—but George wouldn’t have wanted any of it. So perhaps that’s how one gets a nice, short, mostly new, but curiously underdocumented collection.

As I’m sure you know, the cover pic of George is from when they were filming the scene in Help where they all dive into water fully clothed and iirc, emerge in a swimming pool. It was filmed using the pool at the Hotel Balmoral (?) Where they were staying in the Bahamas. I’ve seen many pics of them filming in this pool, and from what I can gather it looks like George may have been having an argument with Paul. That might explain why George looks so angry in this particular photo.

I didn’t remember that, @Linda–it’s been a while since I’ve watched Help! (Though given George’s interest in Hinduism AND comedy, that film is certainly key to the rest of his life. Who could’ve imagined?)

One of my big turn-offs with respect to George was how dismissive he was toward The Beatles and their fans. I remember a quote of his where he described his image as a Beatle as “a shirt I once wore”.

I always found it odd that George so disliked the Sgt Pepper/MMT music John and Paul wrote, yet George’s BFF was Jeff Lynne, who made a hell of a career out of mashing up the best bits of Pepper and MMT and regurgitating it to the 1970s record buying public.

he described his image as a Beatle as “a shirt I once wore”.

I think that’s a perfectly fair and fitting (ha!) way of looking at it. It was ten years of his life, and he didn’t care to be forever defined by it. I don’t see any disparagement of the Beatles’ artistry in there, which he did sometimes seem to do, and yes that does make my eyes roll a bit. But I think it distressed him the most to have the image of “Beatle George” continue to define him to the world as a person (he seemed to blow hot and cold about people regarding his Beatle music as his best and definitive work; that’s a whole other ball of wax).

John didn’t like it either, though he was of course more proactive about shattering the image and building a new one in its place (all the while expecting to retain the deference afforded him by virtue of his Beatlehood).

Paul seems to mind remaining “Beatle Paul” not at all; for him I think it’s the same concept as the “Elvis sending his car on tour” thing, about which he’s frequently enthused. Like, “By all means! Send out the Beatle Doll Voodoo Straw Man! Let ’em beat that up instead of me!”

Then someone should have reminded George that the main reason he could shag groupies and buy flash cars was because of “a shirt I wore once”.

George, god bless him, overrated his own work and his own abilities. Were it not for Lennon/McCartney, Geoff Lynn or Tom Petty et. al. dear George would still be singing plagiarized versions of others’ hit songs.

@Mike, I’m not sure I agree that “George wouldn’t have wanted any of it.” When it came to music, he wasn’t stingy, and when it came to the unreleased stuff, he did oversee and to all evidence endorse the All Things Must Pass anniversary edition, which was quite an elaborate production. There are different kinds of generosity, and when it comes to celebrities “giving of themselves,” there can be a fine-to-invisible line between paying back the love of their fans and feeding their own narcissism.

George may not have been generous with his psyche, but he was always generous with his work. Except for the layoff of five years or so preceding Cloud Nine, he never stopped producing, even when he was fucked up and uninspired, even when his sales plummeted and his reviews stank and everyone had written him off; even when he was nearly stabbed to death by, guess who, a “fan.” He was working on Brainwashed, his best album since All Things, up to the moment his cancer made it impossible to go on. And all the way through, he was producing films, recording soundtrack one-shots, playing tribute concerts and charity concerts, sessioning on others’ records, making three albums and loose tracks with the Wilburys, etc. Plus tending his gardens and his family in the privacy he’d more than earned. He didn’t owe any of us more than he gave, and he was perfectly okay with that even when we weren’t.

@J.R., their differing attitudes to fame is another way the Beatles are so perfectly unique yet complementary. Quite obviously, George was conflicted about fame in a way that none of the others really were. Ringo seemed to accept it rather blithely, rather gracefully. John was in classic love-hate with the audience, clutching it desperately close and then telling it to fuck off and fend for itself. Paul’s whole attitude was, and remains, “Come right in, here’s a cup of tea, let’s chat, just don’t try to probe me too deeply.”

George, I’d like to imagine (because I don’t know, any more than any of us knows), was serene in feeling that, as a musician, he wanted to present himself publicly as a musician, not as a politician or an all-around entertainer or a party animal, roles that the other three Beatles played throughout the ’70s and ’80s. And it’s worth bearing in mind that John Lennon went much farther than George ever did in dismissing not just the Beatles, their music, and their fans, but the entire generation that elevated them and the singular historical importance of it all. Meanwhile there are plenty of quotes you can find from George where he says entirely the opposite. It’s who you want to be annoyed by, and when.

On Brainwashed, almost at the point of dying, George sang “Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”: “I don’t want you / But I hate to lose you … I forgive you / ‘Cause I can’t forget you … “ It breaks my heart when I hear that, because I know he’s singing to his fans–to me.

@Karen, if you’re going to plagiarize, you should at least improve on your source. “He’s So Fine” is adorable, but “My Sweet Lord” is a bell-ringer.

On Brainwashed, almost at the point of dying, George sang “Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”: “I don’t want you / But I hate to lose you … I forgive you / ‘Cause I can’t forget you … “ It breaks my heart when I hear that, because I know he’s singing to his fans–to me.

Oh Devin, me too. It’s such a beautiful cover and so perfect and I just love it. (I admit my one-track fannish mind also hears it as a possible message to Paul).

Except for the layoff of five years or so preceding Cloud Nine, he never stopped producing, even when he was fucked up and uninspired, even when his sales plummeted and his reviews stank and everyone had written him off; even when he was nearly stabbed to death by, guess who, a “fan.” He was working on Brainwashed, his best album since All Things, up to the moment his cancer made it impossible to go on.

Good points all. He was generous with his work. Was he generous in his feelings toward the people who bought said work? That I’m not sure of. Perhaps the inherent problem of the “reveal yourself on command” format of interviews applies just as much to George as to Paul. Obviously it’s easier to go to Grouchy-Quippy-Land in that situation than to bubble over with heartfelt warmth toward strangers. Both extremes may have been equally present in George’s private mind and heart, but obviously the former offers the path of least resistance while talking into microphones.

“Ungenerous” may not be exactly the right word @Devin; what I’m trying to acknowledge is a kind of anger, a kind of vituperativeness, a kind of sourness, that George regularly expressed towards the public, his public, which he cultivated on purpose by becoming a rockstar. Personally George seems very generous; and certainly he was professionally generous. But in Buddhism there is something called “the ‘pinch’ of generosity.” Here’s a quote from Gelek Rinpoche, a Tibetan lama:

Was giving ukeleles to friends or $250,000 to Bangladesh something that ‘pinched’ him? Apparently not. Interacting with fans did, and he showed that endlessly. We all can come up with examples. I’m not saying he didn’t have a right to how he felt–it was how he felt–and nobody can blame George for wearying of megastardom, or feeling the physical threat, especially after Mark David Chapman. But George can come off as actually disdainful, like we were all fools for caring about music at all, or being interested in him as a person. As if only yogis, and his particular favorite yogis, are worth our attention. But as an Indian friend of mine once said, “In India, we’re very skeptical about spiritual teachers. They’re all over the place; we understand they’re just people, with human failings. Westerners, they fall for the act; we take the good, and leave the rest.” George was a Beatlemaniac for yogis; he might say it was for Krishna, but I’d dispute him on that. George was a hero-worshipper, and even though Paramahansa Yogananda, Swami Vivekananda and A.C. Bhaktivedanta might be better people to emulate than John Lennon or Bob Dylan, George’s irritation with us for worshipping him was rooted in his own suspicion that he had this flaw in spades.

I can’t help but note that the Beatles who expressed the most disdain towards Beatles fans, John and George, were the two that suffered violence at the hands of fans. John and George understood that what happened with the Beatles was a specie of religious experience, but were driven by their personalities to throw cold water on that in a particularly ungentle way. For this lack of gentleness, one was burned at the stake, and the other almost. Totally appalling, but totally predictable; that’s how the human animal acts.

Lennon’s attitude towards the fans was different than George’s, more like a king addressing his unruly subjects, by a person who always wanted to be King and accepted the tradeoffs. George, on the other hand, seemed to resent the scale of Beatledom so intensely–even though (let’s be honest) he could’ve gotten off that train at any time. If the mania was so sickening to him–if he was so tired of being an excuse for others to go mad–why not say to the others, “Listen, I’m not touring in ’65.” Brian Wilson did it. Or why not ditch out before Pepper?

My issue with George isn’t that being a Beatle didn’t have a massive downside–it did, and any reader of this site knows it–but how he seemed determined to blame others for his own choices. He couldn’t seem to wean himself off the perks of mega-stardom (money, access, drugs, groupies), all of which he knew were powerful illusions retarding his spiritual growth. Still, the biggest block to his growth wasn’t indulging in cocaine or sleeping with naughty ladies, but projecting his own self-hate over this stuff onto others.

I’m convinced that self-hate is a large reason why his pounding the drum for Krishna fell on largely deaf ears. A student of the Zen teacher Thich Nhat Nanh once told me a story. “I asked Thay (TNN’s nickname), ‘When do you know when someone’s ready for ordination as a teacher?’ and he said, ‘When they’re happy.'” George may have been happier than most, but his obvious anger and unhappiness towards strangers who had nothing but affection and appreciation for him, ate up a lot of his credibility. You and I are not responsible for George Harrison’s karma, and him getting angry at his fans for being fans is as silly as a kid getting angry at clouds for raining. I understand why he did, but it was useless, self-defeating, and pure Maya. “If things were only as I wish them to be, all would be well…” All IS well. The kid climbing over George’s garden wall is as much a part of creation as the garden he so cherished.

My issue with George isn’t that being a Beatle didn’t have a massive downside–it did, and any reader of this site knows it–but how he seemed determined to blame others for his own choices. He couldn’t seem to wean himself off the perks of mega-stardom (money, access, drugs, groupies), all of which he knew were powerful illusions retarding his spiritual growth. Still, the biggest block to his growth wasn’t indulging in cocaine or sleeping with people, but projecting his own self-hate over this stuff onto others.

I totally agree, @Michael. As I said elsewhere, it’s possible this impression we have is distorted, or unbalanced, due to the looking glass of fame through which we’re viewing him. But working with what we have, that is what I see, too.

Your thoughts have made me wonder if part of this resentment and critical attitude toward his fans, came from an awareness that most of those fans weren’t as messily embroiled in the material world as he was. Perhaps merely out of lack of access, sure — but as you say, George could have limited his access to it, too. Maybe the average person doesn’t spend as much time as George did pondering ethereal truths, but most people don’t really have time to do so. But they still work hard, try to do their best, try to do what’s right, and love their families and friends deeply. None of that is particularly glamorous, but it has great spiritual value, too, not least because it’s rooted in action, rather than pondering. That’s not to say I don’t value meditation/prayer/reflection, because I do, very much.

I used to think this contradiction in George was the result of blind, well, hypocrisy. Now I wonder if it was a conscious (to some degree) projection of self-contempt onto others. Maybe even some form of envy. (I’m not sure whether I feel that’s better or worse?) And I further wonder if this attitude of George’s might also partly explain his seeming resentment of Paul down through the years (though obviously there were very legitimate causes for resentment mixed in there too, not to mention love). To our knowledge, Paul’s never been one for the sort of spiritualism that George practiced… but he was faithful to his wife. And he’s rarely appeared to be ostentatious with his wealth — for heaven’s sake, he lived in a two-bedroom house with four kids until 1982. Then he moved into a 5-bedroom house. You know?

In fact (and as I type this it sounds so massively presumptuous that I must state immediately that the following is the rankest of speculation), maybe George would have had an easier time giving up “material things” like sex with groupies if he had traded “I want to be an enlightened being” for “I don’t want to hurt my wife” as a motivator. Perhaps he would have called the latter a mere “earthly” motivation, but it might well have served him better. (This is a very good example of why I often have big problems with the more ascetic tenets of various religions/philosophies.) I have never seen a source for this, so it might well be bunk, but floating out there is a “quote” from Olivia that she “felt as replaceable as the furniture” to George. That’s very sad.

@Annie, what I perceive in George is resentment that fame/money/power allowed him to indulge himself in ways that so-called normal people cannot. Could you resist your wildest material dreams? I’m not sure I could, even as a middle-aged man with a rapidly cooling will-to-power. With all the Beatles, there is a removal of any limitations after about 1963, and this is a very strange and unhealthy place to live. Lennon was right on when he called them “emperors,” and Suetonius is probably as good a guide to what it was like to be a Beatle as Anthology.

For this reason, I find it unlikely–not impossible, but unlikely–that Paul was absolutely, utterly, 100% faithful to Linda. One does not go from “hunting the female hordes” to being a one-woman man like that; or maybe one can, and he did. Who knows, and I don’t care. The salient thing about Paul and Linda was that they absolutely loved each other, and were in a committed partnership until Linda died. Who knows what rules Paul and Linda’s marriage had–the important thing is that they both seemed to abide to them happily.

As George did not…much to Olivia’s chagrin it seems. So was George a hypocrite? I wouldn’t call him that; I would say more that he was attempting to be the best person he could be, and sometimes failed. There is a concept which you may have run across called “spiritual bypassing”, which is “the use of spiritual practices and beliefs to avoid dealing with our painful feelings, unresolved wounds, and developmental needs.” That’s the theory; in practice it is writing, “You’ll stay on the fucking label. Hare Krishna.” Eventually George’s spirituality seemed to mellow and deepen, and I find that version–the private version–more authentic than the early years. Remember that a practice takes a lifetime, and George was only 58 when he died.

Another, perhaps even more useful tool for understanding George is Chogyam Trungpa’s “Spiritual materialism”:

Laying all this at George’s feet may seem like pretty heavy criticism, but we should look at it with appropriate compassion. Human beings do these kinds of things, and George would’ve had to have been some kind of superman to turn from Beatle to sadhu in a single bound. Chongyam Trungpa himself was, in addition to being a great Buddhist teacher, an alcoholic. We shouldn’t overemphasize the fact that George fell into these traps, nor should we airbrush George’s flaws so that he’s more of what we think a “spiritual person” should be. His striving towards more knowledge, more wisdom, more “perfection” was absolutely real and absolutely laudable, and has encouraged innumerable people to do the same. This is an unalloyed good. George’s striving, his infidelity, his scorn for fans–his compassion towards Bangladesh, his appetite for cocaine–all these must be viewed as part of a larger, very strange picture, and I am never dissatisfied when my default setting towards these guys is compassion. Hell, I wasn’t George; who am I to judge?

A final point, just from personal experience: I know it seems strange, but well-defined and diligent meditative practices, especially under the tutelage of a teacher (as George did them), are extremely earthly, extremely strenuous activities. They are the opposite of pondering or woolgathering or windy supposition. This is why spiritual bypass is so appealing (“I’m doing all this goddamn work, so I must be a better person than people who aren’t”) and why spiritual materialism is so seductive (“This has to be leading to something!”).

Sorry if this is unclear or I lost the thread; I’m tired.

@Michael: I absolutely agree that sustained spiritual practice can be intensely demanding, and I’m sure George took on that challenge with sincerity and dedication — and that much good came of it, for him and for others.

But I still draw a distinction between that and day-to-day, mundane, messy, earth-bound toil, pain, and pleasure — and I’m leery of philosophies that privilege the former over the latter, that regard the body as something that must ultimately be “transcended” by the spirit. For my money, the two are symbiotic, yoked partners; the one feeds and strengthens the other; symbol and symbolized (each equally real) harmonizing to create peace and wisdom (I say this coming from a spiritual philosophy that defines the soul as body+spirit, if that helps clarify my perspective). Does any of this soapboxing apply to George? I don’t know, really. But it seems relevant, to me.

I sense that George’s own struggles with material-materialism led him to throw the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak. In my experience, an overemphasis on the spiritual (at the expense of physical), can lead to greater, more dangerous pride and selfishness than the reverse — at least for some people. And I think George mistook for a badge of spirituality his feelings of alienation from “the world” (and by extension the people in it, especially his fans). That bothers me. He had every right to feel that alienation, of course; fame clearly hurt him very much. But nurturing a sense of separateness can lead to a sense of specialness, and finally to one of superiority. I worry that in his worst moments George looked with disdain upon the “materialist” strivings of others — others who had none of the material security he enjoyed and who for all he knew were, in their own ways, just as engaged in self-improvement as he was, thank you very much.

So I’m not so much into transcendence over the body. Transcendence over the ego is an entirely different and entirely crucial matter. (And I appreciate the passages from Chogyam Trungpa that you posted; they offer insights of a new and different flavor for me.) But that ego thing is so damn hard. A wilderness, all roads out of which are fraught with mirages and trapdoors and rabbit holes that send you in circles or suck you in and spit you out ten paces behind where you were to begin with.

You make a good point about Paul — it’s very possible that his sexual fidelity was (and/or is) less than 100% — though like you, I was trying to speak to how George’s spiritual materialism (can you tell I love that phrase?) may have fed his disdain/pride/whatever more than his weakness for earthly pleasures. My point was more about… how some “good ol’ fashioned”/mundane/lowly motivators (duty, labor, responsibility, even tradition) might have served him better in accomplishing some of his spiritual goals than an explicit focus on those spiritual goals (BEING good; BEING spiritual; BEING enlightened) did. Does any of this make sense? Some variation on “putting the cart before the horse”? Or the old “you can only get what you want when you stop obsessing about it” conundrum?

“Hypocrisy”: you are right; that is probably too strong a word. I am just trying to explore the nature of these contradictions in George, and how they functioned within him; did he lack self-awareness in this area, or was he aware on some level — possibly in a way that fed his resentment? And absolutely: compassion is instructive, proper, and comforting when dealing with these men and their extraordinary experiences. As Devin said: exploring them as whole people, the good and the bad, is an act of respect — exploring their personal failings not to condemn, but to understand.

Devin, while I appreciate your sentiment toward George, I don’t agree. I give George all the credit in the world for All Things Must Pass and the Concert For Bangladesh. Unfortunately, after 1971 George was only generous with his work because HandMade, Friar Park, FPSHOT, and George’s other properties around the world were super-expensive to maintain and continually required a constant infusion of cash. George would never have participated in the Anthology if he hadn’t been strapped for cash, and in some scenes he seemed to grudgingly interact with Paul and Ringo.

I can understand why George held resentments toward John and Paul. They treated him like a kid. However, George also brought that kind of treatment on himself when he tried to break into the caste-within-a-caste that was Lennon and McCartney. I recently read a 1964 NME article in which a reporter documented George interrupting an interview between the reporter and John. “What are you talking about?” George asked. “None of yer business,” John replied as he took a cigarette out of George’s front pocket. Later in the article, George tried the same thing with Paul when the reporter asked Paul about his mindset when he set about to write a rocker. “I was just thinking,” George interrupted, “what about [Little Richard song] Bama Lama Bama Loo?” “Shut up, George,” Paul responded. “You just write daft songs. As I was saying, I liken writing a rocker to painting an abstract…”

I don’t see that last anecdote as George “bringing that kind of treatment on himself.” I see it as Paul being a total dick.

And interrupting an interview with some lame comment wasn’t?

Well, it’s hard to say without actually hearing it. The Beatles often interrupted or spoke over each other, butted in to make jokes, etc. That’s just how talking works. Paul insulting George personally is different and just plain mean, IMO (though maybe it would come off more as a joke in the audio, but it would still be a be a mean joke).

@Annie I have to agree. Even without hearing the audio no matter how you think about it Paul comes across here, as just your average bully. I have often wondered what George’s constant complaints and his general disgruntled attitude toward Paul really was about. As far as I could tell the only thing on record seemed to point to John bullying George, not Paul. Even that scene in Let it Be didn’t cut it for me. I could never understand why people always pointed to that scene between Paul and George as an example of Paul “upsetting” George or “giving him a hard time”. I thought, “That’s what you call giving someone a hard time? This is the behavior that George is thinking of when he attacks Paul in interviews? You’ve got to be kidding…” I thought John’s behavior toward George which was actually caught on tape, was a lot nastier. However George was always attacking Paul while John seemed to get a pass. Well after reading this little exchange, I think I finally get it. I wonder how many times over the years did Paul talk this way to George? Times when it wasn’t recorded on a journalist’s tape recorder. I would bet there were many more incidents. I’m beginning to see now, why George was always gunning after Paul. There is also an angry accusation from Paul to George that has been floating around for years. While they were recording Tell Me Why, George apparently makes some sort of “mistake” during a take and Paul can be heard angrily berating him. I thought maybe that was an isolated incident but perhaps not?

Is there any way you could share the article this anecdote is from? I’ve been searching for it for ages now, but I can’t find any mention of it outside of here on dullblog. It’d be much appreciated, thanks.

@Linda A:

Yes, I’ve no doubt Paul can be snappish and nasty — especially when his frustrated-perfectionist dander is up. I think Paul in his own way is as moody as John, and for just as legitimate chemical/developmental reasons (despite the conventional wisdom that John’s moods were the vicissitudes of genius while Paul’s were the tantrums of a diva bitch or whatever). And there’s really no excuse for Paul running George down like that, basically out of nowhere. One Beatle insider (Ken Scott? One of the Tonys? I forget) reported walking into a session and being “appalled” by the way Paul was bossing George around. He didn’t give any details, so it’s a little hard to judge, but I have no doubt George frequently took a lot of demoralizing treatment.

And George may have resented snappish bossiness from Paul more than John’s cruelty and dominance because, well, as George put it, John was the “sort of guy you’d march behind into war.” He was a natural object of hero worship, so people probably felt he had a right to that mantle of authority which, despite his insecurities, he wore quite effortlessly. That is very appealing and persuasive. OTOH Paul’s bossiness is more of the anxious, self-conscious, passive-aggressive variety, which is much less attractive and much less motivating.

Perhaps George respected John more on an artistic level, too.

And I still stand by my comment that George might have felt freer to criticize Paul because he knew it wouldn’t burn bridges between them, whereas John had proved that when sufficiently angered, he could get very Ahab in his need to hurt and humiliate. Not to mention that he ultimately did cut George off over something petty, so if that’s what George was thinking, he was right. I often wonder if Paul took the brunt of George’s combined resentment of him and John — in much the same way George seemed to take out his John-problems on Yoko. I saw it summed up brilliantly by a commenter on another board: “Somebody else was always going to be on the business end of George’s John-rage.”

All that said, I think Paul and George were closer, even during the Get Back sessions, than is generally recognized. I don’t know that this is true, but I have heard from trustworthy sources that George used to call Paul up for long talks into the wee hours about what a mess they were in, and that Paul was also the first Beatle George told about his mother’s cancer diagnosis.

@Annie I couldn’t agree more. Paul is definitely as moody as John. I have never seen him as the chirpy chappy he has long been thought of. That’s his image. I also think Paul’s temper could be as vicious as John’s. I find it interesting that Bob Wooler told Mark Lewisohn in an interview, that Lennon and McCartney reminded him of the cold blooded killers, Leopold and Lolbe. I was shocked to read that, and I wondered if Wooler wasn’t using hindsight (after the 21st Birthday beating incident) with that comparison. I still wonder why he chose that comparison. He didn’t seem to elaborate on his reasons. But I took note that he was not only referring to John, but both Paul and John. Anyway regarding your comments above, there was definitely an interesting dynamic going on, and a fixed hierarchy that fueled the dynamic between the three front men. Yes indeed Paul and George may have felt more comfortable to criticize and be mean and petty to each other. And yes I do believe they were much closer to each other than the common myths would have you believe. I think the Paul and George relationship is one of the most interesting because there were so many layers . It’s way more interesting to me than John and George.

@Linda A:

I agree Paul can have a bad temper. Some of his worst moments are quite chilling, in fact — the nasty postcards sent to Derek Taylor (and his wife!) in the summer of ’68 come to mind. And I don’t at all like how he apparently tends toward a YOU OWE EVERYTHING TO ME attitude when fighting with people under his authority or receiving his support. And yes, the “Leopold and Lolbe” quote is eyebrow-raising. :/

That said, I can’t agree with this: I also think Paul’s temper could be as vicious as John’s. I think Paul can be mean in a snappish way (as in the “you only write daft songs” line), fierce and ruthless in pursuit of something he wants (the perfect take, legal success, privacy), and irascible when in pain. But he’s never struck me as someone who actually enjoyed hurting and humiliating people just for the fun of it.

“I often wonder if Paul took the brunt of George’s combined resentment of him and John — in much the same way George seemed to take out his John-problems on Yoko. I saw it summed up brilliantly by a commenter on another board: “Somebody else was always going to be on the business end of George’s John-rage.””

I think that’s very astute, Annie. And I wonder, too, how much of Paul’s bossing George around was fueled by Paul’s frustrations/anger with John. Paul and George were safer targets for each other when either was angry with John, I think. And they were the two who were really jockeying for position within the Beatles pack, with John being the clear leader and Ringo the clear follower. This is reminding me of the comments on the Lewisohn thread about the way the pack-bullying shifted from George to Paul during the Hamburg stints — another indication that they occupied the same basic “tier” in the Beatles hierarchy.

And the thing about that, @Annie and @Nancy, is how the second-place jockeying was bound to get much, much more intense once Lennon had abdicated, after May 1968. It suddenly wasn’t just about internal band politics, it was for the future existence of the group. Who was going to hold down the fort until John came back to his senses? (Which he would’ve done and eventually, I believe, did–only problem was that by that time they were in a lawsuit.) This “hold down the fort” mentality is how you get John and Paul doing “The Ballad of John and Yoko” as a duo, and the three of them doing “I, Me, Mine”–the goal was just to keep a steady stream of music coming out until John came around.

After May ’68, John was already pissed off–for reasons only he knew, or maybe didn’t even know himself–and so there was a lot more pressure for Paul and George to turn on each other. Add to this George’s increasing fecundity (and quality) as a songwriter, and all the oft-stated issues–Paul being “bossy,” George wanting (and deserving) more cuts on the albums–become inevitable and unsolvable. But to me these things are as much about John as they are about Paul vs. George. What they should’ve done–what John should’ve insisted upon, as the leader of the group–was cutting John and Paul’s lesser work, however they defined that, in favor of George’s best. But that was impossible, due to John’s H-fueled paranoia, and that Yoko was constantly whispering to John that he was a genius and the others were hurting her feelings, and so forth. This made John get even touchier and even more territorial, even though the rest of the group was bending over backwards to accommodate John. The fact is, at no point during the Beatles did Paul, George and Ringo make John do anything he didn’t want to do. And yet John still left the group–and this is why I’ve always thought that the breakup was primarily an artifact of John’s inner life, not externally caused. And it was certainly not Paul trying to take over the group.

As John turned up the heat past boiling, George acted one way–“I’ll go with you, John; you’re the important thing.” Paul took a different tack–“I’ll go with the band; the band and the songs are the important things.” In the end, Paul was more right than George, first because had it not been for the lawsuit, it’s likely that Klein would’ve done to the Beatles what he did to the Stones–the songs, and the band’s legacy, were under threat; and furthermore, even though George supported John to the hilt in every major band decision after May ’68 (Klein, not touring, Spector), and played on lots of John’s solo work, John still ended up finding some reason to hate George and cut him off by 1972. George sacrificed the Beatles, and his friendship with Paul, to save his friendship with John. But he got neither, because the problem was between John’s ears.

@Michael:

even though George supported John to the hilt in every major band decision after May ’68 (Klein, not touring, Spector), and played on lots of John’s solo work, John still ended up finding some reason to hate George and cut him off by 1972. George sacrificed the Beatles, and his friendship with Paul, to save his friendship with John. But he got neither, because the problem was between John’s ears.

Well said. Specifically, George even supported John through the “HDYS” war-on-Paul, and even after that John went off to Playboy (or whatever) making disparaging comments about George — including a pronouncement that Paul was more intellectually sophisticated than George. Sheesh! No wonder George went kaboom with that “I did EVERYTHING you asked me to! But you were NEVER there for me!” meltdown.

“I did EVERYTHING you asked me to! But you were NEVER there for me!”

Here’s the whole incident, transcribed from May Pang’s book, and I give George huge credit for that blowup. As I read, I realized that John was reaching out to George in 1974-75, during the Dark Horse tour, when John wanted to be a musician (and, I believe, a Beatle) once again. Of course George would resent that, and see that at least some of it was John’s running back to his old friends because Yoko was no longer in the picture.

All three of them had been treated terribly by John since they returned from India—and I say this assuming that at least some of the oft-repeated chestnuts regarding Yoko were true (George’s “bad vibes,” Paul’s nasty little “hot shit” note). Even if it was time to move on, JohnandYoko were the love affair of the 20th Century, and so forth, you don’t treat your friends like John treated Paul, George and Ringo, and expect them to be there for you afterwards. You don’t even treat co-workers like John treated the other Beatles. I suspect it all could’ve been healed by a sincere, heartfelt apology, but it’s clear that John Lennon didn’t DO those. You can chalk it up to Liverpudlian macho, but it just seems like classic immaturity to me.

Particularly as I’ve gotten older, I’ve always felt the “Lost Weekend” story was utter bullshit, the same kind of revisionist narrative that John spun so compulsively whenever Yoko was in his life. That’s the whole reason behind “Lennon Remembers,” for example; and for as much truth as there is in what he says, I also hear an insecure husband making an insecure wife happy. If you listen to John’s music from the later part of the Lost Weekend, it’s his best work since Plastic Ono Band; he’s charting again, with his own stuff and with Elton and Bowie–in other words, he’s doing what he loved to do and did so well, not just drinking and drugging himself to death. Whether or not they would’ve ever been JohnandMay, it’s clear May Pang isn’t just a groupie. He’s reconnecting with Julian, something he should’ve done years before. And if you hear him give interviews or guest DJing at WNEW, Lennon’s loose, funny, not pushing some Concept of the Moment, recognizably the guy he was from 1963-67. John may well have been kicked out in 1973, spent a lot of time drinking and drugging in 73-74, but by 1975 his star was ascending again…Then before the year is out, Yoko appears and he suddenly wants to retire from the business altogether, and drops all his friends for the second time, including Paul, who he was going to write with during the Venus and Mars sessions.

Does this feel like true love vanquishing all? Not to me it doesn’t. We all knew people in high school who fell in love, HARD, and for as long as they were in that relationship, treated everybody else like crap. Then, after it blew up (as it had to), they’d come back, sheepish and apologetic. That’s what I think was going on during the so-called “Lost Weekend”: John humiliated, finding himself in a bind, then quietly reaching out to his three closest friends–apologizing but not apologizing. Ringo he had always stayed friends with, because they demanded little of each other; George never took John back (and that’s why John was so hurt over I, Me, Mine–it showed the public George thought John was a shit); and Paul took John back, only to have the same thing happen to him that happened in 1969. John simply wasn’t strong enough to be married AND have his own friends. Which was a real shame, not just for Beatlepeople, but for John.

@Michael: What do you make, then, of Paul taking a message to John from Yoko, laying out how he’d need to win her back? Some people see it as a practical move on Paul’s part, like, “I’ll help Yoko out and then if John does go back to her she’ll owe me and won’t keep me away from him.”

@Nancy:

Agreed that George and Paul took out some of their John-frustrations on each other. John had a remarkable knack for pitting his friends against each other.

Going back to Linda A’s comment about Paul’s treatment of George: People often look askance at George’s continued public snarking at Paul, especially since Paul didn’t (or very rarely did) snark back. I wonder if that was because Paul knew only too well why George had some residual bitterness. Of course you could say that maybe George should have got it out of his system by the time they were both middle-aged. But the Beatles years were the formative of their relationship, and of course there were business tensions that dragged on for decades…

This is a long reply to both Annie and Michael (you’re forewarned)!

Annie, on the question of why Paul evidently took a message from Yoko to John: I suspect it was a mix of the practical (hoping some gratitude from John/Yoko would enable him to have more access to John) and the idealistic/romantic (believing that John loved Yoko and that they should work it out). Paul’s got a reputation as always focusing on the main chance, but I think he’s also a crazy romantic, as his no-pre-nup marriage to Heather Mills attests. I think there’s also evidence that Paul felt badly about the way he treated Yoko in the last days of the Beatles; if I’m remembering correctly, in an interview John says something like “now Paul’s sorry, but it’s too late.” Which says a lot about John’s willingness to hold a grudge, IMO.

I don’t think it’s entirely fair to say that “John had a remarkable knack for pitting his friends against each other”: Paul and George both chose to curry his favor, and John clearly enjoyed being the Alpha dog in the pack, but I don’t know how intentionally he set the two at each other.

I’m sure George’s bitterness toward Paul was founded to some degree on real ill-treatment. I still find his continual snarking at Paul to smack of jealousy and immaturity, though.

And Michael, I completely agree that “the breakup was primarily an artifact of John’s inner life, not externally caused.” And the turmoil that resulted from John’s checking out of his role in the band absolutely seems to have driven the Paul v. George battle to more painfully destructive levels.

One last thought: In his last set of interviews, I believe John said that Paul and Yoko were the only two people he had chosen to be “full artistic partners” with, and that that “wasn’t bad picking.” That had to hurt George (and comfort Paul a bit for “HDYS” and John’s slagging him off in interviews after the breakup). It seems John could only fully respect people who would stand up to him and be willing to take that almost to the point of no return. There’s no question that John was furious at Paul for quitting the band (the “he didn’t quit, I sacked him” line shows just how furious he was), and later for suing. But I think he also had some respect for Paul’s strength of will (and maybe also belatedly realized that Paul had been right about Allen Klein). George’s loyalty to John in the late 60s/early 70s not only brought him nothing, but may even him cost him some respect from John.

I could write a whole post (and I might) about John’s decision to go back to Yoko in the mid 70s. Here I’ll just point out that May Pang wasn’t strong enough to partner John for long: only two people were, by his own account. That both Paul and Yoko have reputations as tough business dealers and demanding bosses isn’t accidental.

@Nancy wrote:

Annie, on the question of why Paul evidently took a message from Yoko to John: I suspect it was a mix of the practical…and the idealistic/romantic

This seems right to me.

“now Paul’s sorry, but it’s too late.” Which says a lot about John’s willingness to hold a grudge, IMO.

@Nancy, does that sound like John, or does that sound like Yoko? Is undying animosity between John and Paul (and John and George, too) sound like something John wanted, or something Yoko wanted?

John and Paul were, by both men’s admission, brothers. They’d “called each other every name in the book.” And yet Paul’s treatment of Yoko from 1968-70 totally destroyed that bond? For every “Jap tart” anecdote there’s a “two saints” one. Paul accepted Yoko’s presence in the studio remarkably easily; he even gave interviews ca Abbey Road basically giving the union his blessing–and this is from a guy who apparently liked Cyn just fine, was loving to Julian, etc. So to any normal standard, was Paul horribly demeaning and disrespectful to Yoko from May ’68 to ’70? Not from what we know, here on the outside.

Similarly, the real wedge between John and George seems to have been John’s refusal to play for Bangladesh; initially John agreed, then un-agreed after it was clear that the invitation was just for him, and not for Yoko as well. But Yoko wasn’t a pop star, nor had she worked with George for 12 years. Did Bob Dylan refuse because Sarah wasn’t invited? “I’ll never forgive George for not inviting my wife, Mrs. Leon Russell, who plays excellent sea chanteys on the theremin.”

I could write a whole post (and I might) about John’s decision to go back to Yoko in the mid 70s. Here I’ll just point out that May Pang wasn’t strong enough to partner John for long: only two people were, by his own account. That both Paul and Yoko have reputations as tough business dealers and demanding bosses isn’t accidental.

I’ll be interested to read that post, @Nancy. An initial thought: “strong enough” is a very very weird way to look at marriage. The reality is, John didn’t need a minder, and he didn’t need a mommy. He survived—actually thrived—between the period 1958-62—between Julia’s death and his marriage to Cynthia. And he basically conquered the world (’62-68) while in a marriage which he treated with the utmost casualness. It’s only after Yoko arrives that this idea he was flawed or self-destructive or a little baby comes into play, and we must step back and ask, “Where the hell did he get that idea, and why did it stick in the face of all this evidence to the contrary? What changed, and why?”

Getting back to George, I think it was his not buying of this idea—none of the Beatles really bought it—that made a friendship with John increasingly impossible.

@Nancy:

I don’t think it’s entirely fair to say that “John had a remarkable knack for pitting his friends against each other”: Paul and George both chose to curry his favor, and John clearly enjoyed being the Alpha dog in the pack, but I don’t know how intentionally he set the two at each other.

Yeah, it may not have been a conscious thing; maybe that’s the only way John knew how to operate, and soothe the void within. But too many members of John’s “entourage” ended up at odds, so eager were they to curry his favor (and/or not “set him off”) for me to think it’s just coincidental tensions between the entourage-ees. Lewisohn states examples of it over and over again: Stu/Paul, Stu/George, Exis/Paul, George/Paul, I think Shotton/Somebody, too (?), etc. And he notes that “Once again, John sat back and watched it happen.” It’s a classic dysfunctional family dynamic. I think John was very good at manipulation.

and the idealistic/romantic (believing that John loved Yoko and that they should work it out). Paul’s got a reputation as always focusing on the main chance, but I think he’s also a crazy romantic

I agree that was probably part of it. Haha, I’ve seen him described elsewhere as “psychotically romantic” (we can put that in the Paulexicon along with “pathologically positive”). And his description of her coming round to Cavendish as “this diminutive sad figure in black” would support your take. Yoko’s impression is that Paul did it because he wanted to “save John” from his LW self-destruction (which might just be Yoko-spin, but whatever) — this was, of course, at the time when she confirmed that the event had taken place, despite her initial denial that it had not, and that it was just something Paul “needed to believe.” Presumably she originally denied it because it clashed with the “John was constantly begging to come home” story.

Eeek, um, anyway, to get back to George (I’m sorry, I’m doing it again!), Yoko actually visited him too in this bid for help getting John back, as is revealed by the rather insufferable Al Aronowitz in this article (http://www.blacklistedjournalist.com/column62.html), which has lots of info/observations on George that might make good fodder for discussion here.

Relevant portion: “Once I was there when Yoko Ono showed up. This was during that lull in her marriage when she sent John off to tryst with May Pang. As I recall, Yoko spent an entire day at Friar Park lamenting to George and to Pattie about how much she missed John.”