- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

When Victoria, a regular commenter here on Dullblog, asked if she could write up a review of John Green’s out-of-print book Dakota Days, I immediately said “yes!” I remember reading it as deep background for my comic novel Life After Death for Beginners, and finding its glimpses into soothsaying and John and Yoko fascinating and maddening in equal measure. Here are her thoughts. Enjoy.—MG

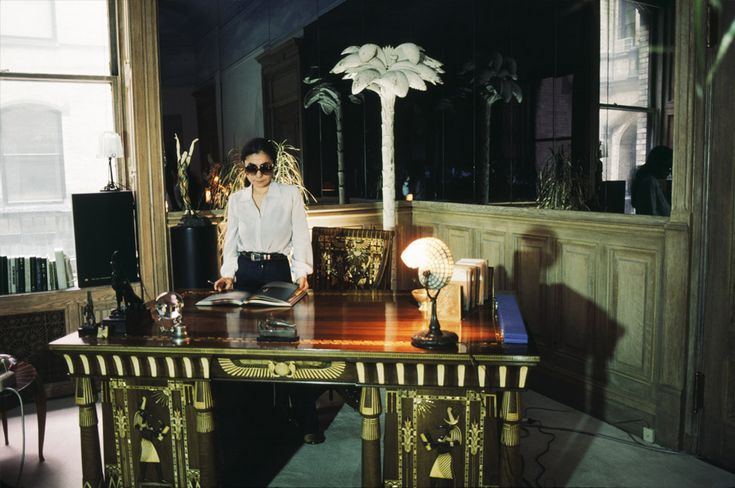

The Dakota, a Renaissance Revival building constructed in the 1880s, is well-known as a glamorous and sought after residence, and as the site of supernatural happenings in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. Beatles fans know it, however, as John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s residence from 1973 onward, and the backdrop to the probably most contested period in Lennon-Ono history.

The Dakota, a Renaissance Revival building constructed in the 1880s, is well-known as a glamorous and sought after residence, and as the site of supernatural happenings in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. Beatles fans know it, however, as John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s residence from 1973 onward, and the backdrop to the probably most contested period in Lennon-Ono history.

Some time ago I read Peter Doggett’s You Never Give Me Your Money: The Battle for the Soul of The Beatles (2009), a readable and magisterial book that deals primarily with the Beatles dissolution and aftermath. In it, Doggett remarks, “Authorised and unauthorised accounts of Lennon’s life in the late 1970s vary so widely that both are unbelievable,” going on to contrast the Lennon-Onos’ 1980 interview talking points—John as happy house-husband, focused on child-rearing and baking bread—with reports from other sources that depict John as creatively, emotionally, and spiritually deadened. Indeed, in her excellent 2016 book The Beatles and the Historians: An Analysis of Writings About the Fab Four, past Dullblog commenter Erin Torkelson Weber describes the competing narratives around Lennon’s last years as forming “another of the great unresolved debates in Beatles historiography.”

This debate—certainly ongoing here on Dullblog—piqued my interest to seek out Dakota Days, one of the counter-narrative publications, and the first of the three (!) John-centric memoirs published in 1983—the others being May Pang and Henry Edwards’ Loving John, and Pete Shotton and Nicholas Schaffer’s John Lennon: In My Life. Fred Seaman’s Living with Lennon, due to be published in January 1984, eventually appeared in 1991 as The Last Days of John Lennon.

Dakota Days is the memoir of the Lennon-Onos’ chief tarot reader John Green. The book opens with Green’s first meeting with John Lennon: freshly returned from his ‘Lost Weekend,’ a panicked Yoko has called Green in to read for him. However, John Lennon did not meet John Green that day, but rather… Charlie Swan. The reason for the alias? Yoko first claims that John would be jealous that he and Green have the same name, but the real reason is that Green had previously used his tarot reading skills in order to locate Lennon at his hotel at Disneyland in Florida in late 1974—incidentally, this was where and when John signed the papers to legally dissolve the Beatles—an act of supernatural detective work that Lennon didn’t kindly take to, and Yoko had assured John that she’d gotten rid of that psychic. Therefore, at Lennon and Green’s first face-to-face meeting, John Green became Charlie Swan. John apparently never knew the real name of the man he called Charles, or ‘the Oracle.’

In Green’s account, Yoko is a difficult and exhausting blend of imperiousness and extreme anxiety; she calls him at all hours of the day and night, asking him to reading on every aspect of a topic. If even half of what Green says about the demands Yoko placed on him is true, he certainly earned his paycheck. She comes across as more overwhelmed than wicked, detached and distressed by turns, always intensely concerned about John. Green doesn’t pass judgment on her directly, but it’s overall an unflattering portrayal, and his decision to include certain details—Yoko’s tendency to refer to employees or staff as servants, the fact that she apparently smoked through her pregnancy—hardly implies that he thought well of her.

For his part, John is a man of changeable moods, variously upbeat and morose, cruel and accepting, jocular and serious, insightful and vacant. He has intense preoccupations—finding the Spear of Destiny, researching Celtic history, following the coverage of Paul’s Japanese incarceration (“not that I care, you understand”)—but not a lot of focus, and a tendency towards self-absorption and torpor. Wrestling with the loss of his muse (for which he openly admits the house-husband narrative was a cover story cooked up, in fact, with Green’s aid), John clearly needed more social and creative outlets in this period of his life. In Green’s description, John spent virtually all of 1978 ensconced in his bedroom watching television on mute and chain-smoking joints, though he’s on the upswing in 1979 and 1980, with the Bermuda trip as an important turning point. Via Green, we see John indulge in long and rambling narratives encompassing everything from his views on friendship (tending toward the nihilistic and transactional), his identity crisis (there is an evocative description of himself as a series of ghostly forms that he peels off himself and places around his room), his relationship with Yoko (complicated), his relationship with his sons (complicated), to his attitude toward Paul (complicated).

Through Green’s eyes and ears, we witness Yoko mostly fretting and planning. Of the things she’s reported to have said in Dakota Days, the part that has probably gotten the most attention is when she talks about Paul. Green quotes her as saying:

It’s a pity, really. I like Paul! I think of him as a friend. John is the one who doesn’t like Paul. Paul was always the cute one and John was jealous of that. When I first met Paul I was attracted to him. […] That’s why I was getting close to John, so I would be near Paul if he wanted to make a move. […] I think that he [Paul] was always a little interested because of the way he looked at me.

The fact that she approached Paul before John is, by now, widely known—and who knows, maybe in his swinging bachelor man-about-the-London-avant-garde-scene phase Paul did once give her the gladeye—but the whole thing really comes off as wishful thinking. Green reads the cards and diplomatically tells her: “He seems to have gotten over his infatuation with you”. There’s also a bunch of rivalry toward Paul and Linda (just why were the Lennon-Onos so weird about Paul and Linda’s marriage?) As always, Green relays these conversations without passing personal judgment.

As portrayed in Dakota Days, the Lennon-Ono’s own marriage is a strange dynamic indeed: there are moments of warmth, unity and thoughtfulness, and even a Druid remarriage ceremony, but also underlying dysfunction, a strong sense of tug-of-war sometimes turned cold war. There is an obvious element of selection bias here—at times when things are going well, people don’t need as much advice or validation from the mystical consultants in their life; nor does peaceful coexistence make for good copy—but even so, this does not seem to have been a stable or emotionally mature partnership. In the Estate/Goldman debate, John Green comes firmly down on the Goldman side (more about that later).

As described above, Yoko comes off poorly in Dakota Days. At the same time, John often seems like a nightmare partner. Something that I think a lot of discussions about John and Yoko and their relationship underrate is just how difficult it must have been to be in a relationship with someone as intense as John, who, by many accounts, had an almost bottomless need to be validated and entertained. Green flat-out says as much at a couple of points:

John openly resented his wife’s growing interest in a subject other than himself, no matter how closely related to him that subject was, and expressed his feelings with stinging hostility.

[…]

John did have a long-established pattern of early support followed by sudden withdrawal. What he required above all was Yoko’s undivided attention. So long as her ideas kept her focused on him, he would support them. But as soon as she started off on her own, John would withdraw his energy, knowing that this would force her back to him. This pattern extended to everything from travel plans to her musical career.

In light of this, a lot of Yoko’s own behaviour makes more sense: it’s really no surprise that she often seems to have dealt with things by disengaging and/or focusing on things that she did have control over, such as their business affairs, planning elaborate visits to Japan, sending people off on auspicious directional trips, or, indeed, buying an Egyptian mummy who she believed to be the reincarnation of herself. Overall, these two badly needed a therapist who specialised in helping couples develop healthy communication and conflict resolution skills.

After chapters of Lennon-Ono marriage drama and Apple machinations, things kick into gear in the most enjoyable chapter in the book, where Yoko, Green, and Yoko’s art dealer friend ‘Dan G’ (Sam Green) go to Cartagena, Colombia, to meet a witch. Now this is the kind of story you want from a psychic adviser’s memoir! We have John Green and Lena (here named ‘Nora’) using their knowledge of toad magic to size each other up, with Green noting for the reader’s benefit that he doesn’t specialise in amphibian philtres. Sure! There are many mystical rituals, culminating in a candlelit, sulphur-infused ceremony in which a dove is sacrificed and a contract is signed in its blood—and at the last moment, Yoko loses her nerve and implores Green to do the signing! He makes her squirm with the knowledge that he didn’t sign his own name to this particular Faustian bargain. Just great stuff.

After chapters of Lennon-Ono marriage drama and Apple machinations, things kick into gear in the most enjoyable chapter in the book, where Yoko, Green, and Yoko’s art dealer friend ‘Dan G’ (Sam Green) go to Cartagena, Colombia, to meet a witch. Now this is the kind of story you want from a psychic adviser’s memoir! We have John Green and Lena (here named ‘Nora’) using their knowledge of toad magic to size each other up, with Green noting for the reader’s benefit that he doesn’t specialise in amphibian philtres. Sure! There are many mystical rituals, culminating in a candlelit, sulphur-infused ceremony in which a dove is sacrificed and a contract is signed in its blood—and at the last moment, Yoko loses her nerve and implores Green to do the signing! He makes her squirm with the knowledge that he didn’t sign his own name to this particular Faustian bargain. Just great stuff.

However, bruja-hunting in Colombia aside, Dakota Days contains a lot less occult hijinks that I was hoping for from the memoir of a professional tarot reader/psychic. If you changed all the references to tarot readings with references to business meetings or on-call marriage therapy, the book would change relatively little. It does, of course, benefit Green to portray himself as a canny adviser rather than a man of mystical practices and black magic arts, given the obvious credibility hit his account would take from leaning too heavily on the latter, but it’s still a bit of a let-down.

It’s a truism to say that fortune tellers, mediums, and people of that ilk are really in the business of reading people: Dakota Days is essentially a book-length masterclass in this, and openly so. We see Green repeatedly use his readings to reframe a situation, provide reassurance, or deliver sensible advice; at one point, Green directly states that his main role in John and Yoko’s life is to play marriage counsellor and business advisor. Green does seem to have put a lot of work into their business affairs; there are whole chapters about dealing with ‘the Apples’, buying dairy cows (apparently a surprisingly lucrative investment!), investing in real estate, acquiring Egyptian relics as investments.

To a modern Beatles fan, it may seem bizarre that a random tarot reader had such sway in John and Yoko’s lives and dealings, but it’s not so surprising when you consider that this was the 1970s, an era of drug abundance and occult cachet, and the kind of people John and Yoko were. John and Yoko both harboured suspicions of conventional professionals, with some justification; Yoko’s mistrust in doctors is not unreasonable when you consider the fact that she was forcibly committed to a mental institution as a young woman, for example, and John had been subject to a lot of questionable business decisions in the Beatles era. In addition, Yoko was clearly strongly influenced by traditional Japanese cultural beliefs. One of Yoko’s key consultants was ‘directionologist’ Takashi Yoshikawa (called ‘Mr K—’ in Dakota Days), an expert in katatagae, a Japanese system in which the directions taken during a journey possess important meaning and value. As with other people in the Lennon-Ono orbit, Green at one point went on a round-the-world trip calculated for its auspicious direction. Another of their card readers was Frank Andrews, who darkly proclaimed to Yoko: “Your husband sleeps in blood.”

To a modern Beatles fan, it may seem bizarre that a random tarot reader had such sway in John and Yoko’s lives and dealings, but it’s not so surprising when you consider that this was the 1970s, an era of drug abundance and occult cachet, and the kind of people John and Yoko were. John and Yoko both harboured suspicions of conventional professionals, with some justification; Yoko’s mistrust in doctors is not unreasonable when you consider the fact that she was forcibly committed to a mental institution as a young woman, for example, and John had been subject to a lot of questionable business decisions in the Beatles era. In addition, Yoko was clearly strongly influenced by traditional Japanese cultural beliefs. One of Yoko’s key consultants was ‘directionologist’ Takashi Yoshikawa (called ‘Mr K—’ in Dakota Days), an expert in katatagae, a Japanese system in which the directions taken during a journey possess important meaning and value. As with other people in the Lennon-Ono orbit, Green at one point went on a round-the-world trip calculated for its auspicious direction. Another of their card readers was Frank Andrews, who darkly proclaimed to Yoko: “Your husband sleeps in blood.”

For his part, John had a classic looking-for-the-one-true-answer personality—serially infatuated with the Maharishi, Janov, Ono herself—with its shadow twin of inevitable disillusionment. They were intelligent but also credulous, talented but superstitious, impractical people who had enough money to insulate them from the usual consequences of such impracticality. I hate to use the word ‘mark’, but perhaps it would have been more surprising if John and Yoko hadn’t had a coterie of spiritual advisers.

You could easily come away from Dakota Days assuming our narrator was simply a guy on the make, but Green did in fact have genuine occult bona fides (of which more later). Still, even just on a storytelling level, imagine how much more entertaining this book could have been if it, say, used a different tarot card as a motif for each chapter, or had been structured in seven parts matching Green’s seven tasks?

Speaking of storytelling, one of the weaknesses of Dakota Days is Green’s copious use of dialogue. He defends this, saying he has a good memory and that working with the Lennon-Onos was memorable, and also disclaimers that some conversations are reconstructions. However, his use of dialogue is truly excessive: in many chapters, it forms the majority of the text. While some quoted lines have an believably Lennonesque ring to them—“long time no seer”, “Little Mystic Sunshine”, “Capitol punishment”—there is no way that even the least critical reader can swallow this much dialogue as being anything close to accurate remembrance.

There are, of course, a number of ways in which Green’s book seems self-serving. Green meets John Lennon, superstar, and immediately establishes a rapport with him; Green’s advice is always sound (and things go badly when his advice is not followed); Green is always able to say things just so; not long before John dies, he visits Green’s apartment for the first time ever and delivers a kind of summary speech. I can believe that Green got on with John and that he gave John and Yoko some decent advice—frankly, that wouldn’t have been difficult—but there’s a lot that I suspect he played up.

It’s also interesting to consider what Green left out. To his credit, he’s frank about the fact that he’s not telling the whole story and has omitted certain details for privacy reasons, but also that his position only provided a certain view onto the Lennon-Onos’ lives. He writes in the introduction:

One of John’s favorite references was to the story of the six blind Hindus describing an elephant. One would hold the ear and say that the elephant was like a leaf. Another would press against the side and say, “No, no, the elephant is like a wall.” Each in turn touched a different part of the elephant and assumed that that part was the whole. So do we all when we attempt to describe the truth.

[…]

I do not claim here that this book is the whole story of John’s last years, for that would be false. This is the part of the story that I saw and shared, day by day, year by year.

John Green himself emerges as something of a cipher. Dakota Days is so tightly scoped to Green’s association with the Lennon-Onos that we learn very little about the man himself. The only real personal details that I picked up are that he was a large man in both stature (6’7”) and bulk, that he was divorced, and that he’d studied art education and child psychology. We also know from the book’s copyright page that he was born in 1947, making him late twenties to early thirties during his association with the Lennon-Onos.

Cross-checking against other sources is invaluable here, particularly Albert Goldman’s notorious Lennon biography The Lives of John Lennon (1988), for which Green and his circle were all interviewed; Goldman filled no less than six folders related to John Green. Although Goldman’s biography has numerous and well-documented issues, the research he conducted was and is highly regarded; if you can sift through Goldman’s lurid brand of editorializing and backtrack through the muck to triangulate what his sources are actually saying, there is useful information to be gleaned from his book.

According to Goldman, Green discovered his psychic powers when studying art education at the State University at New Paltz (NY). He then married a classmate and taught for a year before moving to NYC and working at Financial World magazine, before becoming the protegé of Joseph “Joey” Lukach, a renowned witch with links to Santería. In 1974, following the breakup of his marriage, Green was living with a woman named Wendy Wolosoff (who now practices as a healer). Goldman also mentions at various points that Green had a disciple, other clients, and also managed a New Wave singer called Mande Dahl. (Dahl is still around; there’s even a photo of her from 1981 captioned “John and Yoko’s” on her website.)

We also get more details on certain things that Green skims over in his book: how Green and Yoko first met (she needed an exorcist for her haunted apartment), the Florida detection (Green’s self-proclaimed “neat trick” here carried out with a distinct lack of mystic arts), and finally the Green-Yoko split. Yet another justification for the name of Charlie Swan is offered. In exactly the kind of ominous portent that Dakota Days could really have used more of, Goldman reports,

The name has a numerological significance, but its basic meaning is metaphorical. As John Green explained to his friend Jeffrey Hunter, “The swan is a symbol of hypocrisy. Though it appears to be pure white, when you lift up its feathers and examine the skin, you see that underneath it is all black.”

One Goldman-reported episode unsurprisingly omitted from Dakota Days is the painting scam that the two Greens, Sam and John, pulled on Yoko. The details can be found (and judged) in Goldman, but briefly: the two plotted together to sell her a painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir where the Greens inflated the price and pocketed the difference—a plan which worked, although John Green’s girlfriend broke up with him over such unethical behaviour. Instant karma, baby. But as far as Yoko was concerned, the two Greens had never met before they all went to Cartagena together. In his book, John Green portrays Sam Green as something of a wheeler-dealer: that may be accurate, but there’s an element of disingenuity there. Dakota Days also makes no mention of how Yoko eventually kicked John Green out his residence in the Lennon-Onos’ Broome Street apartment.

What happened to John Green after his time in Lennonland? He was briefly based in Virginia in 1983, as detailed in this Medium article by a woman who knew him in that period, after which he moved to LA. The comment section of a 2010 book review of Dakota Days gives more possible information about him: if those commenters are to be believed, Green also spent time in Washington DC, had family ties to Santería, and was displeased with his book’s title and the fact the manuscript was extensively trimmed. Green is apparently now deceased. I haven’t been able to find any interviews with him, and there are no known photographs of him. Curiously, it doesn’t seem like Green did much promo for Dakota Days; in the comments of the book review linked, a woman identifying herself as Green’s widow says that he turned down interview requests after the book’s publication. Decades later, “Charlie Swan”—perhaps appropriately—remains a shadowy figure, with a legacy within Beatledom that is decidedly mixed.

It’s hard to fully size up Dakota Days. Green is telling a story that is believable in its broad strokes, but there are some clear shortcomings and self-serving elements to it too, along with flat-out incorrect details. Cross-checking with other sources simultaneously bolsters and diminishes Green’s credibility: these stories are broadly substantiated, but we can also see that Green is sometimes selective in his telling of events. We should weight his testimony appropriately, while also valuing the insights that we can glean from his close position to the Lennon-Onos in the Dakota years.

Given that it was Peter Doggett who sparked my interest in the topic to begin with, I was excited to see that he was publishing a book about John’s Dakota years; only to be dismayed by its cancellation for undisclosed reasons. Here’s hoping that Doggett’s manuscript eventually sees light, and we get some clarity on this period in John and Yoko’s life.

Dakota Days is long out of print, but can be borrowed from the Internet Archive here.

Thanks for giving me the chance to publish my musings, Michael!

I didn’t get into it above, but one thing Green doesn’t talk about is drugs – there’s just the reference to John spliffing up during his 1978 ‘lockdown’. But I’d be surprised if pot was the only thing in the mix. (I’ve heard that later Yoko admitted to having a heroin relapse in 1979 or 1980? Haven’t looked up the source for that though).

Anyway, I think that their behaviour makes more sense if you consider that they were in ~altered states of mind~ at times. e.g. Yoko saying all that stuff about Paul (if, indeed, it actually happened) makes more sense as drugged-out rambling.

Very curious about what other Dullbloggers made of Green’s memoir! (As well as my take on it 🙂

– Victoria (formerly posting as Kristina)

You’re very welcome, @Victoria!

While I’m here, I want to say a few things about the cultural context of “Charlie Swan.” It was EXCEEDINGLY COMMON for people to have their Tarot read in that late countercultural era; palm reading, I Ching throwing, etc, was as much a part of a certain cultural milieu as macrame and brown rice. Part of this was the hippies’ identification with the occult–rejecting the mainstream Judeo-Christianity most of them had been born into; and part of it is the higher-than-usual incidence of such behavior by celebrities. Becoming rich and famous overnight is a very odd, extraordinary experience, and those to whom it happens often look far afield to make sense of it. Occult beliefs can supply answers to “why me?” “who should I trust?” and “what next?” in a way that conventional religions largely do not. An astrological chart, for example, is a beautiful way to retcon. The Lennons consulted oracles for the same reason that Pompey the Great did.

So it’s not so surprising that–like Nancy Reagan–the Lennons consulted an astrologer. It’s not even so surprising that they hunted for relics and such. One must do something with all that money, and is an amulet really that much different than a fad diet doctor or Arthur Janov? It is actually more surprising that they did not allow such stuff to utterly rule their lives, as Peter Sellers did. Sellers became somewhat paralyzed by all the signs and symbols and, though they were jetting here and there, the Lennons did not. It would’ve been interesting to watch if, in subsequent years, Lennon and Ono would’ve reigned it all in, or whether they would’ve taken more and more directional trips, employed more and more advisers, until they really were living in an alternate reality. Only as the occult became less mainstream than it had been since 1965 would we have been able to separate their attitudes and proclivities from their contemporaries’.

Of course, in Yoko’s case, we don’t have to guess. We know she reigned it in after John was killed. Which, given the circumstances of his death, is strange to say the least. Almost like she never really believed in it at all, but knew he did and used it to manipulate him.

That’s an interesting bit of filigree to the story, @Elizabeth — I will also say that there was a lot less of that stuff, at least openly, in the 80s.

Hmmmm I don’t think so personally. We’re talking years of: seeking constant advice from people like John Green and Takashi Yoshikawa (not to mention the other psychics); doing effortful things like going/sending people on bizarre directional trips, buying a mummy, and going to Colombia to meet a witch; being so into this stuff that every source from this time talks about it.

If subsequently she dropped this stuff, there are obvious reasons why that might be the case. e.g.: culture generally moving on from these kind of practices; her entering a new phase of life after John’s death; her now being in a relationship with Sam Havadtoy (who we don’t know that much about, but there’s no sign he was into this kind of thing). Also, people just go through phases, especially in turbulent times of their lives, that later they move on from. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

‘Erin Torkelson Weber describes the competing narratives around Lennon’s last years as forming “another of the great unresolved debates in Beatles historiography.”’

When we speak of competitive narratives, it’s really only the estate sponsored ones which dissent. The books by Green, Pang, Seaman, Goldman, Giuliano, Rosen, etc paint more or less the same picture with only varying degrees of emphasis and gravity. There are gaps, of course, in all the broad strokes, opening up endless space for motivation, interpretation, and analysis of what was actually going on and why, but the main gist -drugs, apathy, creative oblivion, depression, neurosis, a co-dependent but thankless marriage- always comes across. And that, frankly, makes so much more sense than expecting people to believe that a guy as psychologically complex, volatile, and damaged as Lennon spent five years baking bread and being in love. In fact, that version of Lennon sounds like far more of a vegetable than Green’s or Seaman’s or Goldman’s does. Their Lennon is at turns witty, irascible, sad, petty, warm, funny, crazy. Lots of human stuff. When I think of the bread baking Lennon, I think of that Simpsons episode where Marge protests Itchy and Scratchy, and her anodyne, unoffensive ideas turn them into zombies. “Bread? Please, I made it just for you,” offers a sedate, monotone John Lennon with huge dilated pupils…

Vis-à-vis the consistency of the non-estate endorsed books, one difference between Green and Seaman that IS interesting is how they depict Lennon reacting to McCartney’s imprisonment. In Green’s book, John is actually pretty concerned about Paul. In Seaman’s book, John is positively delighted, cavorting about with borderline demonic glee at Paul’s misfortune.

Which is true? Could both accounts be true? It would not be totally out of character for Lennon to oscillate wildly between both extremes, would it? And also it is true that Lennon was the kind of guy to a) mask his deeper feelings beneath outwardly outré behaviour, and b) alter his behavior based on his company . So if, on one hand, Lennon reacts like a jerk around the young, male assistant, and is more even tempered around the de-facto counsellor, it sort of makes sense.

But I also remember reading somewhere, maybe it was one of Fred’s message board posts, that Green was sequestered for hours in Studio One, actively co-involved in Yoko’s McCartney sabotage plot -a point void from ‘Dakota Days.’ Whether that has anything to do with his giving a more benign version of the episode…

“‘Erin Torkelson Weber describes the competing narratives around Lennon’s last years as forming “another of the great unresolved debates in Beatles historiography.”’

When we speak of competitive narratives, it’s really only the estate sponsored ones which dissent.”

Hear, hear @Matt. Much of my impatience with the dialogue around John Lennon from 1975-80–and indeed even from 1968 on–is how it allows a created, Estate-sponsored narrative to fill in all the gaps without any kind of pushback. And that’s because the Estate can, and did, generate the kinds of documentation that historians and journalists respect–interviews, letters and film. Conventional journalists and biographers take that narrative, and extrapolate in the safest of ways. It’s similar to how Lewisohn acts in the podcast interview I just posted: “We know what J&Y did during the Bed-In while the cameras were on; and after the cameras were off, they must’ve done X, Y, Z.”

The only way to figure out what they actually did was to track down and interview the people around them at that time–which is what Albert Goldman did, love or hate him. Goldman isn’t responsible for what he found; he is responsible for his interpretation, which is so cartoonishly negative it has colored people’s opinions of his research. But those are two distinct areas.

Any serious discussion of John and Yoko, and indeed of Lennon himself, has got to explain the big gap between the Official Narrative–made of, and created by, interviews and public statements–and all the testimony of the others: friends, colleagues, assistants, hangers-on. The Dakota years bring this into sharpest relief, but I’m not really satisfied with the Lost Weekend narrative, either; or The Ballad period. None of it smells right to me.

The standard response is to simply deny all of the secondary testimony (“jealousy! cashing in!”), but that’s a fundamentally unserious response, and that’s why we constantly find ourselves digging at certain issues, looking for explanations. Basic questions suddenly become unanswerable by the public record and require a kind of interpretation that basic questions of an earlier time did not. Whether John and Brian fucked in Spain isn’t necessary to explain John and Brian’s public behavior and private loyalty to each other. John suddenly going with Allen Klein–after a lifetime of being afraid of music industry sharpies–is a big fat WHY?, and it’s at the heart of the breakup.

The moment you recognize that John Lennon was a genius performer, and applied that skill to all aspects of his public self, not just the recording studio, something becomes clear: his life up until 1968 is in most cases logical, predictable, and unified between public and private. But his life after 1968 is much, much less so. It remains deeply performative, while at the same time insisting that it is totally honest–and for me that signals addiction. If your standard of proof is–HAS to be–a memo stating, “I am a heroin addict” there’s simply no way to resolve that debate. But that’s not a problem with reality, or even with data–we have plenty of evidence for Lennon’s being an addict–it’s a problem of applying a method that works passably well for Presidents, sort of, kind of, but really not at all for rockstars. I’m not arguing here that every book about Lennon should be Goldman; but I am saying that much of what people turn their nose up re: The Lives of John Lennon is the application of a looser, more journalistic method of fact-finding which is absolutely necessary to uncover anything close to the truth.

@Michael

Great post! Lots there to discuss, but I’ll limit myself to a couple of points. 🙂

This is something that I’ve been thinking about a lot. The fact is that everyone involved is agenda-driven to some degree – such is the way these things go. And while we certainly can’t take what the Estate says at face value, we also do have to reckon with the fact that a bunch of the people who have spoken do have their own agendas and indeed credibility issues. (Michael, I’ll certainly go into this more in the potential future post that we talked about in email!)

So it’s a real balancing act to try to assess how credible each source is, and how and why they might be distorting the record (which they may not even be doing intentionally!) That’s why I took such pains in the post to look at how John Green’s account tracks with what we know from elsewhere, what caveats there are with his story, etc. We need to be critical readers here: this is a book that requires interpretation rather than just reading.

Michael, what you write about John’s performance of his identity is really on the money, IMO.

Honestly, a big part of the issue here is that John constructed a public persona around two main things: radical truth-telling, and his relationship with Yoko.

I don’t mean to say that they’re not still entitled to privacy, but in the long term, I think they backed themselves into a corner a bit with going so hard on the JohnAndYoko thing.

Sorry to compare with Linda and Paul again, but no one has ever tried to deeply scrutinise their relationship. And that’s mostly because it seems like it was stable and happy. But it’s also because Linda and Paul didn’t promote themselves as PaulAndLinda, a love for the ages, a creative partnership written in the stars, etc etc.

Rosen has also talked about how in John’s diaries, he took a lot of glee in Paul’s arrest.

Like you, I think that all of these things can coexist. I can easily believe that John was concerned and also full of schadenfreude (and probably feelings other things too) at various times and to various people. It also makes sense that he’d save his nastiest venting for his diary.

By the way, this reminds me of something I didn’t mention in the review. Some sources (Goldman, I think Seaman?) have claimed that Yoko engineered Paul’s drug bust. I think this is nonsense (like a famously pot-smoking rockstar needed a tipoff to be searched?!), and this theory doesn’t appear in Dakota Days. In fact, here Yoko attributes it to Paul traveling in an inauspicious direction: “I have been studying his numbers and I can see where he made his mistake.” So there you have it!

Thank you for this review, Victoria! I read Green’s book some years ago and recall thinking that the amount of “verbatim” dialogue was a real stretch unless Green was taping everything (which he doesn’t claim to have been doing). But I do buy some of what Green says — the big picture, as it were, at least as it appeared to him.

One of the things that stands out to me now that I’ve done some reading on the subject of tarot is how out of alignment Green’s readings appear to have been with what seems to be broad consensus among readers now about ethical practice. Not saying we should hold him to those standards, just that it’s interesting to compare what he seems to have been doing with Lennon and Ono to what responsible readers advocate. Ethical readers now don’t read repeatedly for clients who won’t “do the work” based on what they learn, and don’t engage in the kind of “psychic detective” work that Green seems to have done at Disneyland. Green seems to have fostered dependency much more than growth. Maybe that was what Lennon and/or Ono wanted (unconsciously?) but it’s icky to me.

My sense about Lennon’s last days is that they were VERY mixed — some days (or parts of some days) he really was enjoying baking bread and hanging out with Sean, and others he was bored, stoned, and more or less unhappy. And I agree with your point about Lennon’s feelings towards McCartney being up and down. If there’s one phrase that I think describes 1970s Lennon, it’s “internally volatile.”

My understanding is that Green didn’t really see them much face to face. His consultations were mostly done by phone (often in the middle of the night) and he taped his phone calls.

A lot was done over the phone, yeah – that’s clear in the book. I don’t think that Green taped his phone calls. He had to have known that people would critique all of the ‘verbatim’ dialogue in the book, so if he was working from recordings, he could have strengthened his credibility by saying so… and if he didn’t want to admit to having made recordings for legal/ethical reasons, he could have simply claimed to have taken detailed notes. But he doesn’t even do that! He says it’s all from memory.

Related, but Yoko later said that Green had barely ever seen John, and I do think that contact with John is one of the things Green plays up in the book, for obvious saleability reasons.

@Nancy, your comment made me think of something I’ve read: “Two kinds of people get the worst medical care. The very poor and the very rich.” The very rich tend to look at doctors as servants–and I suspect that goes double for mystics. The mystics know that if they don’t give the readings the boss wants, they will be thrown off the cliff.

I spent a few decades with the silly idea that I knew a lot about the Beatles and John&Yoko. But every time I come here I learn something new:

This couldn’t have been helpful to John’s relationship with his old friend. It also might explain why he didn’t want Paul hanging around the Dakota. Who wants to see their wife get all giggly when your pal comes to visit? (Of course there were other reasons he didn’t want Paul showing up unannounced.)

I suspect sharp words were exchanged whenever John&Yoko fought or bickered. John’s famous sarcasm could probably hurt Yoko deeply when he was angry. But at the same time, Yoko could stab back at his self-esteem, paranoia and insecurities by telling him why she got close to him in the first place.

I came up with a theory here a few years ago that the reason so many rock critics disliked Paul was because he reminded them of guys who’d stolen their girlfriends. But imagine John’s level of discomfort after hearing Yoko’s admission!

Yeah, obviously I have no knowledge of any specifics, but what you read about them suggests that they weren’t ‘good fighters’.

Contrast that with Paul and Linda. We know that they didn’t have a perfect marriage (because they said so!), but seem to have genuinely operated as a team, and presumably had more healthy ways to resolve conflict.

@Baboomska Yoko’s statement about Paul is born of the same sort of narcissism that informs her other remarks to Green: she is a star who is infinitely more talented than her husband. John is OK, but what people really want is more Yoko, even if she has to put subliminal messages in the music to trick people into making her songs bit hits. (This is actually a discussion in ‘Dakota Days.’)

To play devil’s advocate though, Christoper Sanford suggested in his bio that Paul and Yoko slept together when she came to his house in 1966. If true, this certainly does have tremendous implications for what might have gone awry later with John and Paul. But the main appeal for Paul in 1966 (if it happened) would have been that she had a pulse and vagina, not that she stood out among the hordes. And to think that he was gazing across the table at Apple board meetings in 1978 trying to contain himself is totally laughable.

“Who wants to see their wife get all giggly when your pal comes to visit?”

Pardon me for being a little skeptical of this one. Thanks to Get Back, we happen to have several hours of footage of Paul and Yoko in the same room, and to me it appears that all her focus is on John. This is what everyone else has said as well.

@Nancy,

Thanks so much for your comment. As with Michael, I always enjoy reading your takes on things – over at Erin’s blog, too!

That’s very interesting information about tarot reading & clients – I had no idea that there was a code of ethics in that field, haha. That said, I wouldn’t be surprised if those ideas weren’t so present in the 1970s!

I get that. At the same time, John and Yoko demonstrably weren’t going to do that work, were they?

Green also genuinely seems to have been intrigued by the business stuff and ‘the Apples’ and wanted Yoko to succeed in dealing with them, something that gave her confidence. So it may be a grey-area situation all round.

This is so well put, Nancy – I agree with you.

The bread baking thing… I’m sure John did, in fact, bake bread. But to me it has the ring of ‘I did this a few times, now I’m going to elevate this to the level of a major hobby/talking point’.

Who knows though, maybe he actually got really into it!

The more I learn about John and Yoko, the more I see two difficult, strong-minded people who were damaged by their upbringings and suffering a lot of what we’d now call trauma. I think that when their marriage clicked, it probably was the incredibly deep kind of connection we’ve been sold on. But also that when either one of them wasn’t going well, or they weren’t aligned as a couple, they both acted in ways that dragged the other down. Often those kind of dynamics and actions aren’t even intentional, too!

I will admit, I am more sympathetic to Yoko than some people here. Sure, she’s done questionable things, but she’s been through a lot… and I do think she gets unfairly blamed for some of John’s not-so-great behaviour. Also can you imagine being in a relationship with someone who acted to her as John Green describes? Undermining your partner like that is a seriously damaging way to behave.

The funny thing is that the Estate’s narrative about John is now out of date with the times: people are now eager for stories about people who are complicated and difficult, affected by trauma, their highs and lows, etc. Not the old-school stories of rock star excess nor simple tales of triumph, but something more humanistic and based in ideas of mental health.

And John absolutely fits into these kind of narratives, even if he died a bit too soon to fully complete his ‘narrative arc’.

And so that’s where informed fans have landed, even if the Estate hasn’t caught up yet.

Indeed there are ethical guidelines for Tarot reading: Brigit Esselmont’s blog has a good post on the subject. In it she quotes from the guidelines of the American Tarot Association, which describes ethical readers as: “People who help others better hear their own inner guides. They empower clients to think through their options and come to decisions on their own… [They] encourage clients to seek the licensed professional help of doctors, counsellors, accountants, and lawyers – especially in cases where the client’s concern goes beyond the expertise of the reader. They do not use the cards to identify “curses” or “bad energy” and then charge a fee to remove these ‘curses’ or ‘bad energy’.” She also says this about doing multiple/repeated readings for clients:

“There are going to be some clients who keep knocking at your door wanting more and more Tarot readings no matter how often you read for them. It would be easy to see this as ‘easy money’ and a recurring revenue stream. But don’t.

Question the client who wants multiple readings on the same topic or who keeps returning day in and day out.

Tarot readings are great for gaining insight on a difficult situation. However, there comes a point when one really needs to go within for the answer rather than constantly seeking other people’s opinions on what to do.”

As you say, in the 1970s I doubt there was the same kind of codification — or the same kind of awareness about the range of tarot readers. My sense in general is that in the Dakota years Yoko and John were looking for magical answers, in the way many of us do at some points. The interest in numerology, directions of travel, etc. all look like trying to find a way to resolve feelings or issues externally, rather than doing the internal work (which, to be fair, is REALLY tough to do even if you haven’t had a traumatic childhood, as they both did). I heartily wish they’d found a reputable therapist or therapists instead, because it’s clear that, as you say, they were both dealing with a lot.

@Nancy,

The quotes that you give are enlightening – thank you! And maybe (hopefully) there were also tarot readers in the 1970s who had those kind of principles.

But at the same time, those weren’t the kind of people that John and Yoko were going to employ, you know? They pretty clearly didn’t want people who would tell them to actually work on themselves and figure things out.

Yes, exactly. It really seems like they were looking for answers, not realising (or maybe not wanting to accept) that doing the work is the answer.

Just as you say, it’s understandable and even relatable. Working through this stuff is hard! It sucks! It looks like putting in a lot of effort, incrementally, over a long period of time.

We should remember that this was a very different era in terms of the understanding of mental health, too.

Another thing I didn’t have space to mention in the article… what we see of Yoko’s family dynamics in Dakota Days don’t exactly give the impression of a warm and supportive family.

John and Yoko both got dealt a rough hand in that respect.

@Victoria – See, I’ve read a lot of comments on the internet from Yoko apologists about her so-called traumatic childhood, and I just don’t buy it. Where is the evidence? We know that she was sent, with the servants, to her family’s country house for a bit, and that for this brief period (what, one or two months?), she was not treated very well. Big deal. It was the Second World War. Millions upon millions of people suffered much, much worse than Yoko Ono, and they didn’t turn out to be as horrible as her.

I think she’s a product of her childhood, but of having too much rather than too little, and of being taught that she was better than others because she was born into wealth.

@Elizabeth

Hmm, well it’s a bit difficult to answer this comment, but I’ll make a good-faith effort.

The reason that we’re talking about this at all is the fact that you can’t really come away from this book (or other sources) and think that Yoko is a grounded and balanced person. Which then raises the question, what factors influence her psychology and her actions?

I agree that she does seem to have a sense of aristocratic command, without the counterbalancing sense of noblesse oblige that you’d hope for.

However, being raised rich and entitled doesn’t in itself explain the extreme anxiety that Green describes her having, or the unhealthy aspects of her and John’s relationship (and the probable attachment issues underlying that), or her addiction/substance issues, or her need to turn to the occult for answers, or her experiencing clinical depression to a degree that she was hospitalised for it.

She has a superiority complex and is horrible… that may be true, but it’s also insufficient. To me it feels like a character description in a story. Reality is more nuanced, and what we know of Yoko hardly suggests a simple person.

Secondly, here are some things about Yoko’s upbringing that strike me as difficult.

From Goldman: she didn’t meet her father until she was three; she was diminished by her mother growing up; her father suddenly started treating her with chilly distance in her teens; he preferred to focus on his mistress/second family.

From her Wiki entry (sourced): she and her family had to beg for food during wartime; her father was sent to a concentration camp.

And in Green’s book what we see of her dynamic with her mother is weird and messed-up. The family vibe in general seems… off.

I don’t know about you, but to me that doesn’t sound like an emotionally great way to grow up. Personally, I wouldn’t swap with her.

Do these things excuse her bad behaviour (and there unquestionably has been some), no. But they are relevant context in trying to understand her.

For further info on a specific piece of Yoko’s background that would likely factor into any reading of her background:

When Yoko’s chauffeur attempted to blackmail her back in 2006 and it led to a court case a year later, the content of his initial letter was read in open court.

The whole letter is here, but I would draw the reader’s attention in particular to the fourth bullet point in his list (trigger/content warning: description of sexual assault), which, judging by the description of the location, could fall within the timeframe in which her family was displaced during the war…

Yeah, I’ve seen that before. Really upsetting if true, especially considering her age at the time. It’s really shitty of Karsan to have said something like that publicly.

That is a very strange letter. It’s almost as strange as Eliott Mintz finding John’s missing diaries in a rubbish skip. Not quite, but even so. Give me 2 million dollars or I will tell the world that you have said unkind things about your children, made political statements about the US and British governments and that you were raped on a Japanese farm (something that would only make people sympathetic towards you).

It wouldn’t surprise me to find out that Yoko’s chauffeur had a gun held to his head when he wrote this letter. At the very least, you have to wonder what sort of dirt she had on him. Quite frankly, the only person in the world who would care what Yoko Ono has to say about the US and British governments is Yoko Ono.

On the other hand, maybe she has just had a run of very bad luck with her staff. Not to mention her lovers.

@Victoria – Well, I think Goldman must have been mistaken if he said she didn’t meet her father until she was 3. I don’t recall that detail from Goldman’s book, but if he did say it, he obviously didn’t have access to the photographs or film footage showing her as a toddler with the rest of her family, including her father.

Personally, I’m a bit sceptical about the begging for food story. This allegedly happened when the Ono children were sent to the country house and were put in the care of the servants for a few weeks. Yoko spoke about this in one of her bed-in interviews (it’s on YouTube somewhere, I’m sure), but didn’t mention the bit about begging for food. That came later as the story was embellished in keeping with her status as Oppressed Asian Woman.

Look, I’m sure she didn’t have a perfect childhood (did anyone?), and yes, her parents were probably … distant. But isn’t that the case for most children of wealthy parents who are brought up by nannies? She is a product of her childhood, as we all are, but most of us grow up learning the meaning of the word ‘no’, which I doubt she ever did. Understanding her means understanding that also.

@Elizabeth

I mean the picture is very much of inconsistent and critical parenting, difficult family relationships, one parent with another family on the side, etc.

And if she was raised with the sense of entitlement that you describe, then I’d also say that her parents did her a massive disservice there.

I don’t know if this kind of thing was/is commonplace, but really I feel sorry for any kid raised with those kind of family dynamics, wealthy or not.

I simply said that she was damaged by her upbringing, and I think that’s obvious, if only because people with healthy and stable upbringings generally don’t act like she has! But also because of what we do know about her early life, as just mentioned.

I think I just see things as less black and white than you. I can sympathise with the hand Yoko got dealt without excusing her less-than-great behaviour. People can get a rough shake and also not behave in ways I’d condone.

Hi Victoria–I just wanted to say I appreciate your nuanced view on John/Yoko. I am sometimes surprised on this site how much the “equal empathy on all sides” doctrine seems to be disregarded when it comes to Yoko, especially in the comments. So it’s nice to see someone acknowledge that she has her own personal story and narrative as much as the individual Beatles or her&John do, and that her really awful actions don’t discount her as a human or minimize her own hardships.

“equal empathy on all sides” doctrine seems to be disregarded when it comes to Yoko, especially in the comments”

@James, that “equal empathy on all sides” doctrine is really difficult to apply to Yoko for a simple reason: we don’t know very much about her. Five percent of what we know about John? Less? For us to give her the same kind of slack we give John, we have to know details that she hasn’t seen fit to give. “I was raped during the War, so I have a really conflicted view of men. I love them, clearly, I’m attracted to them–but also feel I must remain in charge at all times. So a lot of what might appear to be my dominating John, or controlling him, is that defense mechanism. Which I’m working on. And of course, we’re very different in private.”

In other words: if she talked like John talked in interviews, she’d get the slack that John gets. “Oh, I see why. That makes sense.” Empathy rather than judgment.

Or if she’d been less litigious, and less determined to control every aspect of her husband’s legacy. “I understand Fred’s position; and maybe John did give him the diaries. But I can’t just take Fred’s word for that; pretty soon, everybody would be coming up claiming ‘John gave me this or that’…But I understand why people are so interested, so I’m donating the diaries to x museum, where they will be accessible to scholars.”

Is this so hard? Of course not, it’s Modern Celebrity 101. But with a very few exceptions, Yoko’s behavior has been consistently imperious and unfriendly, she is determined to keep herself to herself. That’s her right–all of it is her right–but the empathy and friendliness towards the other principals receive from the fandom stems from how they treated the fans. George Harrison, for example–probably the Beatle l personally like the most!–comes in for whacks here more frequently than the other three, and I think that’s for the same reason. His aloof and sometimes scornful behavior seems to call the idea of fandom into question and, naturally, fans don’t like that. “Yes! Tell me how I should ‘go get a life’ sitting in your baronial manor, George!” But we know more about George, and so we can forgive him when he is sour. And he is a BEATLE, which means he’s the reason for the season. Yoko gets the kind of critique that Inner Circle gets–Allen Klein or Brian Epstein or Magic Alex.

With Yoko, there’s only so many decades you can read stuff like “the Mopheads or whatever” and not think, “This person doesn’t get it. She seemingly loathes The Beatles and their fans, and doesn’t ever acknowledge where her vast fortune comes from.” That adversarial stance, plus a lack of exculpatory data, makes her harder to empathize with, and easier to judge. This is why I’m always hoping we’ll get more data on her, because I think much of what currently seems like pure dismissiveness in Yoko’s behavior, will be understandable. But to assume that she is good/kind/laudable just because John loved her, or because she’s rich and famous and powerful, or because she’s an Artist, or because she’s Japanese, or because she’s a widow, or because she’s a Girlboss (I swear to God, if I hear once more about those cows…).

The sad thing is, Yoko Ono MAY be good/kind/laudable. She may be a sweetheart; people say that occasionally, and I’m always delighted by it. Someday we might discover that she was vastly misunderstood, and spent her days in selfless charity, and never fired anybody or threatened them or whatever. We may discover it was all terribly unfair–I genuinely hope we do. She may simply be really unsuited for the up-close-and-personal brand of fame her late husband forced into her life. All of that’s possible–but we can only analyze using what she’s allowed us to know. I hope we know more, because Nasty Yoko is not only really boring to think and talk about, it also doesn’t really answer why John adored her. It doesn’t explain her role in the Beatles’ story.

@Michael Gerber

I agree that Yoko hasn’t always helped her cause. As you say, there are so many simple things she could have said in interviews and hasn’t, they wouldn’t even need to be revealing statements.

I think she’s not suited to the kind of fame that puts a spotlight on her personal life, which, fair enough.

I don’t know, a comment like that could be deliberately disparaging, but it also might have been a second-language thing, or even her just poking fun.

(I know the individual quote is not really the point, but I couldn’t resist commenting!)

Yoko’s attitude to the Beatles actually comes up in Dakota Days. John tells Green the story we all know, about how he and Yoko met and Yoko didn’t know who he was. Green thinks that she’s full of it and he tells John,

He goes on to attribute John believing her to John’s poor self esteem in a way that I don’t really buy, but the quote above is a solid read IMO.

I’ve no doubt that the fact that Yoko didn’t really care about the Beatles was a major factor in John’s attraction to her.

@Victoria, it makes no sense that a supposedly hip New Yorker moving in art circles in November 1966 would not know who The Beatles were. It makes even less sense for a working artist having a show in Swinging London to not know who The Beatles were.

I know working artists who show; I know conceptual artists, and their work is especially expensive and hard to sell. People do not buy conceptual pieces to hang over the sofa. So conceptual artists of any competence know when a rich person walks in the door. The idea that John Dunbar hadn’t told Yoko who was coming to the pre-opening, and who they were, and how much money they had, is nuts. The idea that Yoko didn’t know who John Lennon was, or The Beatles were, is nuts. It’s like me saying that when I wrote for SNL, I didn’t know who Lorne Michaels was.

The beautiful thing about a lie like that is you can’t disprove it. Maybe I really had never heard of Lorne, and I was just a natural comedy genius rising on the brute force of an unstoppable talent. But if my wife walked around saying, “Mike wrote for SNL without even knowing who Lorne Michaels was,” reasonable people would think, “That’s a lie, he’s goofy to have told her that, and she’s goofy for believing and repeating it.”

Back to Yoko: why would she say something so unlikely to be true? To attract John, sure — but do we really think that the John of an earlier era would’ve believed her, or been charmed? That’s unanswerable, but it’s worth asking, simply to underline just how weird John was acting; by the time he’s quoting that chestnut in interviews, he’s gone from a reasonably canny adult in showbiz, a tough and tricky business, to a person so gullible he’s practically fetal. (At least when it comes to Yoko. Everybody’s out to screw him, except Yoko.)

A Yoko showing at the Indica in ‘66 who does not know about John Lennon and The Beatles is not “a real artist paying attention to real Art.” She is a dope who’s bad at her job, and Yoko Ono is not a dope. We know this for sure.

Why am I pausing to highlight this item? Because it likely signals a basic desire to snow people, beginning with John. Insisting on a simple, vain lie—similar to the stuff Trump says and his followers repeat—is about asserting dominance. It shows who’s in charge, whether it’s her husband saying it, or a MOMA curator in 2015.

A lot of people enjoy rolling over and showing their bellies; others, don’t. John, post-68, was very much in the former group; people who are skeptical of Yoko’s media image are in the latter. That doesn’t make them Yoko-haters, and we should dispense with that silliness.

It is POSSIBLE Yoko didn’t know who John was, or about The Beatles? Sure. And it’s also possible I’d never heard of Lorne Michaels. A sensible person should be skeptical.

@James

I missed this comment before James, but thank you for saying so! I appreciate that. I think Yoko is a fascinating and complicated person. To reduce her to the wicked witch (or at the opposite end of the scale, a blameless victim/#girlboss) is just lazy, and like Michael said, boring and non-explanatory.

@James

Sorry for butting in, but I am one of those who struggles with the concept of empathy in the context of Yoko and the John&Yoko.

That of course is not to say that she shouldn’t be treated fairly and maturely and deserving of the empathy we strive to afford fellow humans, but rather I wonder how empathy does or does not fit into a rigorous examination of her public statements and, perhaps more importantly, her actions toward others when it comes to the narrative she has constructed.

Lots of words to say that I am trying to tease out, then separate, what is open to a normal and critical exploration of what facts we have.

I think though that what really is a burr under the saddle for me is that for better or worse, Fate taps some individuals on the shoulder and they, by dint of remarkable gifts, talents, or association to those who do are a part of history. I am not saying that these individuals need to vomit out their every thought and their life’s private details, but they should recognize that they are part of something much bigger than themselves.

Yoko, by marriage to John Lennon, became part of a story that spilled the banks of her small corner of the world. I cannot answer where that line should be, but she seems to have repeatedly not properly contributed to an accurate historical record and, in fact, on occasions has actively worked against it.

I know I am naive in thinking this, but at some point could she not just come to grips with the needs, not so much of Fandom, but scholarship and, like Michael Gerber suggests, give all the material to a university?

Sorry for the riff on your post. I just need to work out why I have empathy for the human Yoko, but little to no empathy for the public facing Yoko.

I enjoyed your piece Victoria. I’m not someone who has read a lot about the Dakota days, (too depressing) so I’ve learned quite a bit here.

“The more I learn about John and Yoko, the more I see two difficult, strong-minded people who were damaged by their upbringings and suffering a lot of what we’d now call trauma.”

I’m a childhood trauma survivor, and I can’t imagine where I’d be without therapy. It’s a shame John didn’t get in with a proper therapist.

I’d like to think he may have, had he lived. Only therapy could have helped him I believe. But I get looking into astrology and tarot cards for answers. I was heavily into those things as a teen in the 70’s, and into the early 80’s.

On a side note, I keep hoping after Yoko is gone, that Sean may be more open with information about his parents. Wishful thinking probably,

but maybe he won’t be afraid to let the truth be told. The truth shall set you free. 😉

“Objects, characters, and machines can easily bear the burden of the identities we project onto them. But a human would crumble, walking the lonely road of living up to others’ interpretations of them.”

— Satoshi Hase (Beatless Volume 2)

@Michael Gerber

(replying to your threaded comment – we maxed out the thread depth!)

Oh, I am definitely not trying to argue that Yoko was actually ignorant of who the Beatles were. I didn’t mean to imply that, because as you say it’s pretty ridiculous! Of course she had heard of them and had some basic level of familiarity.

At the same time, I can believe that she hadn’t followed their career or paid overly much attention to them. I think she probably was genuinely wrapped up in her avant-garde scene and hanging out with other artists or the Floyd or whoever and not bothering much with the mainstream of pop culture – and probably consciously rejecting engaging with it. People who are invested in being (or being seen to be) at the cutting edge often are often like that. There’s a degree of hipster snobbism in there for sure.

And also – it’s hard for people like us to understand! – but honestly, Yoko has just never seemed all that interested in the Beatles.

For me that’s one of the most interesting yet unrelatable things about her.

I basically agree with John Green’s take that I quoted above: Yoko was downplaying things in order to bolster her image as A Serious Artist, Actually, and also as an act of mythbuilding. Then subsequently, this origin story became the stuff of legend… and we know that Yoko likes a legend.

It’s hard to know how much John bought into it. Eventually it seems like he swallowed his own hype, but really who knows?

Very cool that you wrote for SNL by the way.

(Thanks for the discussion, too – I’m enjoying it! Thought-provoking as ever)

Yes, I agree with all this.

A person that does something like that is telling on themselves. They are saying, “I am going to lie, especially on certain topics, to make myself look more important. In general, I’m going to be more interested in building myself up than telling you the truth.”

Once we know that about a person, to take what they say at face value—especially on their “hot” topic—is dumb. It’s just dumb. I mean, it’s not dumb if what you’re interested in is some fantasy that appeals to you; but if you’re trying to figure out anything close to the truth, it’s self-deception.

And this is where I get annoyed with people. It’s NOT ABOUT hating Yoko, or loving her for that matter. Unless you know her well, having that intensity of opinion is infantile. It’s not about thinking she’s a Great Genius. She may be — or may not be. On this blog at least, it’s about whether we should trust what she says about The Beatles, and examining her behavior in their story.

I don’t think Yoko is remotely trustworthy on the topic of The Beatles (or John for that matter); and when John seems to be parroting her outlook—you can hear it in both Lennon Remembers, and the 1980 interviews—he should be taken with a big big grain of salt. Yoko’s been very consistent about The Beatles, and Paul. She’s as interested as we are; she just doesn’t adore them like we do. But as fans we so want this story to be a positive one, and have everyone in it love them as we do, so we gush over retconning like “Get Back” because it makes us more comfortable.

Yoko gives us a real opportunity —- an opportunity to decide what our fandom is about: the happy story we like, or the much more complicated story that really happened. Either is fine, as long as you’re honest about it.

RE: SNL — My relationship with the show was complicated so I don’t speak about it much. But, yes, it was fun to hear my stuff on TV. I very much enjoy making people laugh. 🙂

To me the interesting question is WHY Yoko made a point of saying she barely knew anything about the Beatles. Whether she realized this or not, the Lennon of the late 60s was, I think, looking for someone to tell him the Beatles weren’t a big deal. I think he was looking for an out, consciously or not, and she gave him one. Going off with a capital-A artist so cool she thinks the Beatles are boring isn’t just sloping off and leaving a band, it’s making a Cultural Statement. That quote from Lennon about going from the Paul boat to the Yoko boat is very telling. Lennon wanted not just to leave the band, but to go toward something. And going toward the conceptual / experimental art world seemed to give him that.

Is there really any question why she said that? She’s a snob who needs to be in the dominant position. And because John was obviously into submission (and perhaps humiliation), violins played and The Ballad was born.

To me, the interesting thing is the difference between 1957-66 John, who seemingly would’ve reacted with scorn, and post-acid, post-touring John, who reacted with bemusement and attraction.

Without launching a whole new John and Paul Lovers type thing (god I’m begging you please don’t), I don’t think one can really make much sense out of John and Yoko without reading about kink.

Oh don’t worry I NEVER want to experience anything like that thread again! I’m sure the “kink” angle has something to do with the dynamic of why Lennon was captivated, rather than irritated, by Ono’s apparent indifference to the Beatles. I’m suggesting that, in addition to / beside that, he was looking for an escape hatch from the Beatles phenomenon. He had to leave on his terms, and for something he could present to himself and others as higher/better. Leaving “pop” for Art seemed to fit that need.

I agree with you, Nancy. The leap from ‘low culture’ to ‘high culture’ is an important piece of the puzzle.

Yeah, I’ve never discussed it (and won’t get into it, since this isn’t the time/place!), but it’s almost impossible for me not to read them this way.

I also remembered that part in Doggett’s YNGMYM, where he evaluates Goldman’s book, and mentions how Goldman “pinpointed Lennon’s almost clinical need for domination by a strong woman”.

If not here, where @Victoria? If not us, who? 🙂

I’m teasing, but only just. I am sure there are many places online full of knowledgeable kinksters, but none of them will have logged the PAINFUL HOURS of J/Y contemplation necessary to untangle a relationship that, if it was unconventional, worked so hard to hide in plain sight. You have to know J/Y well to get behind the media-scrim of the Ballad.

And I’m not talking about vanilla with D/s undertones; that’s obviously in play here. I”m suggesting something much more formal, with each playing by an agreed-upon set of rules. There are lots of issues to discuss:

1) Had either of them experimented with D/s before? Any evidence for that?

2) While it’s plausible that Yoko went on to have similar power dynamics in her other relationships (it seems unlikely that Sam Havadtoy was in charge), it doesn’t seem like May Pang and John (or Cyn and John) had anything like a similar dynamic to Yoko and John.

3) There’s a definite cooling from Yoko’s side after 1971. Does kink help explain that? Was John and Yoko from 1975-80 the same as 1968-71, or different?

In all seriousness, I’m a bit burnt out on Beatle Sex Lives, but that having been said I think people well-versed in these types of relationships might be able to explain both John’s and Yoko’s behavior in ways that a vanilla relationship model has not been able to. Or maybe not.

@Michael Gerber

Heh, a unique qualification. Thought-provoking questions… personally, I’d be surprised if they were doing anything that was very formal – would either of them have had the clarity and communication skills for that? All signs point to no.

It does seem that way re: Yoko cooling off on things in the early 1970s. I wonder what was going on there. Maybe it’s as simple as the shine coming off and the intensity of dealing with John, who really does seem like a classically codependent type. It’s really difficult to be in a relationship with someone like that.

Remember John humiliated her by having sex with another woman at a party? I really think she never forgave him for it.

Maybe, but on the other hand, it was 1972. Stuff like that happened a lot, and I’m not at all kidding. Talk to anyone in the counterculture in 1972 and–suffice to say that the mores were different. Yoko might well have been ranging widely herself, only…more privately.

While we might hear about that incident and go, “She would’ve never forgiven him, and held a grudge and x, y, z,” we might be right. Or…it was 1972, she yelled at him after, and that was that. 🙂

May always impressed me. She was a young woman cast in a very strange situation, in a period of instability, drug use, bad influences etc for Lennon…and yet she did have some understanding of what was good/healthy in life for John and attempt to steer him in those directions. Reconnect him with Julian, actually seeing and communicating with the old Beatles, moving back to NY (suburban area) and out of the toxic LA situation. She was a very young woman (24) navigating a volatile rock god through a difficult time

I do feel Yoko started to get worried that she could lose him permanently and that John and May may get to a point where a true love/connection started to blossom. I remember hearing a story about it had actually gotten to a point where John refused calls from Yoko…that must’ve really spooked her.

I think she legitimately loved him and had there been a true, permanent break from Yoko, Johns life with May from 1974 onward would’ve been one of the best possible outcomes for him. True the dynamic between them wasn’t quite like like John/Yoko, but I think May could and did play that strong female lead with him, and he did show a willingness to follow (like her ordering him to call Julian once a week) so perhaps as time went on John/May could’ve been like a healthier John/Yoko.

This is absolutely fabulous so so lovely at all

Here is something Yoko wrote on twitter a few hours ago:

Is she even serious with this nonsense? “I didn’t know who he was. ” I realize time waits for no man and we all reach our dotage, but doesn’t someone proofread this stuff?

I could almost, almost that is, feel sorry for her in expecting that people would believe this.

“The first time we met, I didn’t know who he was…”

*sigh*

Yoko’s *still* peddling this proven bullsh*t?

It’s absolutely impossible she didn’t know who John Lennon was at the time…however could she mean in that moment she didn’t recognize this guy as as John Lennon…he could be very chameleon like with changing his hair/look extremely often. So at first glance it was just some regular person, non celebrity, not particularly wealthy or important…but she is trying to say she still felt things for him before being told who he was. Kind of a way for her to say her love for him came from a genuine place

Maybe overthinking it…but I mean when has Yoko ever been called out on this “I didn’t know who he was” nonsense? Never. And she never will be, that’s why she repeats it.

She forgot to mention the year and a half she spent stalking him after the exhibit.

Speaking of the famous meeting at Yoko’s Indica exhibit, does anybody find it odd that in all the endless retelling of this story, the presence of Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate is nearly always omitted? Apparently Polanski and Tate were there multiple times, and spent hours at one point playing with Yoko’s white chess board. I say nearly always omitted, because Yoko *did* acknowledge it in an Aug 2006 Harper’s Bazaar article:

“Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate dropped in. They spotted Play It By Trust – my all-white chess board, and started playing. I was surprised how beautiful and elegant Sharon was. Roman had a certain European elegance in his manner, too. I was totally impressed by both of them.”

That she says here she was totally impressed by them only makes it stranger that they are absent from the other 99% of John and Yoko’s recollections endlessly retold between 1968 and 1980. It’s a major point to leave out. If you were there, and you were giving a recollection afterward, wouldn’t one of the obvious details be the famous film director and his starlet girlfriend playing with the exhibition pieces? It’s the way other events dovetail later on, and the infamous ‘Polanski is to blame!’ drunken rampage, that make the omission curious.

@Matt, what was “the infamous ‘Polanski is to blame!’ drunken rampage”? (Apologies if it’s up-thread and I missed it.)

@Laura One night in LA in 1973 after one of the Spector sessions, Lennon returned home very drunk and started demolishing everything in his sight. He had to be tied down to a bed to be restrained. In the midst of this, he inexplicably started screaming that everything was Roman Polanski’s fault and that Roman Polanski was to blame. May Pang was at a loss as to why his rage was directed towards Polanski.

That too…

The deceit grows old doesn’t it? Well…I guess not for some, but certainly for those, like here, who tend to appreciate facts over mere utterances.

I considered reading “Dakota Days” years ago but upon discovering that the author was John & Yoko’s tarot card reader I passed. I find it kind of amazing that so many commenters here didn’t.

I have a friend who is a tarot card reader, @JLM. She is an extremely astute judge of character. Such folks 1) hear people’s innermost thoughts and secrets, and 2) have a lot of experience reading people.

Ms. Pang is doing a publicity tour for the new documentary The Lost Weekend: A Love Story.

I’ve read May Pang’s book, I think that the documentary would be an interesting watch. Maybe one of the commentariat is willing to write up a review?