- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

Given the political impacts we’re seeing here in the U.S. from internet-driven conspiracy theories, and the prevalence of a (I mean this in the nicest way) Beatles-related conspiracy theory on this blog for the past several years, I wanted to speak a bit about this topic.

I paddled for many years in the shallows of conspiracy theories, most notably ones around the assassinations of the 60s. The big boys, the OG’s. The ones that inspired everything from QAnon to Paul is Dead. You cannot read about QAnon and not think of The Gemstone File.

(BTW, I would argue that PID is a psychological reaction to the trauma of the deaths of JFK, Malcolm X, MLK, and RFK. Maybe throw Manson in there, too. It is the Beatles story retold by a traumatized fanbase, a new myth to fit a darker, bloodier world. Trauma knocks one off-balance, and conspiracy theories are an attempt to regain balance, to reestablish an equilibrium, even a negative one.)

So much to say, I understand the appeal of conspiracy theories…and I don’t think the appeal is what is usually trotted out in the media. I think it’s much simpler, or can be, and often benign. During my Conspiracy Decades, I was not interested in alternatives to the Warren Commission because I craved knowing something secret, wanted to feel smarter than others, hadn’t been educated properly, hated/mistrusted authority, or needed a bunch of facts to fit my political beliefs. The conventional narrative of JFK’s murder fit my politics fine. I was predisposed to secrets based on some family history, but was no more “seeking answers” than any Bigfoot-curious smart kid of my era.

I became interested in alternatives to the Warren Commission after it became clear that the Warren Commission’s version of the President’s murder was crap. Why it’s crap can be debated, but it was, and is, almost comically full of holes. From whatever angle you approach the crime—and it’s important to remember that the murder of JFK is simply a crime—the Warren Commission’s version doesn’t make any sense. Motive’s unclear; means is unclear; opportunity is unclear; nothing fits together unless you force it, and all that force is itself worth noting. It’s 60 years later and there are still books coming out defending the Warren Commission’s version, which means that either 1) it’s wrong or 2) there’s this massive psychological something going on, this massive mental workaround where we can believe all manner of bullshit but can’t believe that particular story. Is that likely? Occam’s Razor says that the Warren Commission is simply wrong.

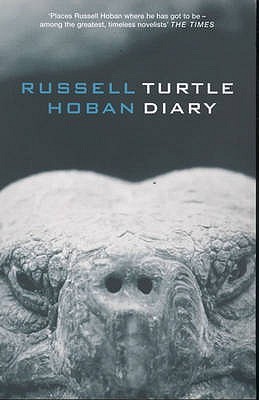

What does this have to do with McLennon, the fan community that believes John Lennon and Paul McCartney were lovers? Everything, really.

It’s in tune with the zeitgeist, sure, but McLennon has gained purchase for a simple reason: the Standard Narrative of The Beatles has some pretty substantial gaps in it. First of all, the Seventies-era idea of John and Paul as merely co-workers or competitors seems to be false, and has grown less credible as the years have passed. And second, the reasons given for the breakup just don’t ring true; “we all grew up”, “those wedding bells”—balderdash. What changed between February 1968, and June 1968 to begin the breakup of the Beatles? As with the JFK situation, the more information we get, the more the Standard Narrative seems to be ignoring or avoiding or perhaps even hiding. Darkness, plus information, spawns conspiracy theories, and bullshit is the best fertilizer of all.

This is what I received this morning, from a dedicated commenter:

Michael, I just wanted to let you know that I have a little more understanding of your distrust of “revised history,” because I’ve been reading the last few days about the Qanon conspiracy and the crazies therein, and W. T. F. That’s not the kind of thing I was connecting a “fresh look/contemporary look” at the Beatles to, but if that’s a connection you were making, then I sympathize a little more with your skepticism. 😀

(I pretty much have to cut myself off at this point from reading about conspiracy theorists for my own sanity in these trying times, but then part of me wants to shout into the void that “do your own research” does not mean “read all the crap posted by other conspiracists.)

Do I have a distrust of “revised history”? Me, who went to a—well, I guess the best way to put it is “an assassination convention”— in a Marina del Rey bowling alley in 1998? I wouldn’t say I’d call it “distrust,” but I will say that I have a profound respect for two things:

- the necessity of history’s constant revision in the face of its misuse by authority; and

- the difficult mental states that departing from traditional narratives can conjure in people.

I am no longer interested in the assassinations of the Sixties, because I eventually realized that this topic was not good for my mental health; the dislocation from the rest of society became too uncomfortable. Still, I had several sound, non crazy-pants reasons to go to that convention. First, I was interested to listen to several scholars that I’d read for years, Lisa Pease and Jim DiEugenio. These are two people of great knowledge and sound judgment that I would recommend to anybody interested in the topic; in a sensible world, they would be tenured professors, and it is precisely their ability to go wherever the data leads them, regardless of consequence, that makes them so admirable. They are obsessed with these topics just like my Yale professors were obsessed with, say, same-sex marriage in the middle ages. So I wanted to hear Pease and DiEugenio talk. Second, I wanted to see a presentation by Phil Van Praag on a recently discovered audio recording of the RFK murder, which apparently demonstrated more shots than were possible by a single assassin.

So: facts, data, scholarship.

Of late, I’ve been asking people making McLennon assertions in comments to provide links, because I want to move them away from feelings and hunches towards facts, data, scholarship. This is a mark of respect to them, but also to the men who are the topic. We have a precious few years before deepfaking makes McLennon “proof” inevitable, so now is the time when the data must emerge. If you’re interested in McLennon, go get that data, if it is to be gotten. You have a year, maybe two, left to prove it.

Writing all this, it occurs to me that it’s more than possible that some of the people at that 1998 convention are now all over the internet, spouting QAnon and chemtrails. They might even have stormed the U.S. Capitol. In fact, it seems likely. So why did I not go down that road?

When I went to that convention I had a very particular stance towards the events at hand. It was history, and it was a hobby. To the degree that it informed my worldview, it gave me a general sense that we should 1) protect Presidents and candidates, so voters’ preferences could be expressed in our democracy, and 2) that the country’s rightwing lurch in 1980 was aided by a great big hole on the center-left. My conclusion from 35 years of reading about the JFK assassination was: political violence is bad. This is the opposite conclusion from the QAnon folks and the Trumpers, and what you conclude counts for a lot.

I did not believe then, and do not believe now, that history would be fundamentally altered if we discovered without doubt that Lee Harvey Oswald was sitting in the lunchroom drinking a Pepsi when JFK was shot, and that the whole thing was a black-op run by James Angleton. Believing otherwise—one fact which alters everything like a magic spell—is a type of poisonous romance which is the opposite of history, and it is not to be trifled with. People sacrifice real things, jobs and marriages and whole lives, on the altar of their obsession. I saw it with JFK; we see it now with Capitol rioters; I want to avoid it with McLennon. So that’s why I pull back on the reins here, often. Not to stifle debate, but to move it towards a form that enriches the debaters, and ties more tightly the mutual bonds of empathy and sympathy that allows society to function.

Not that any of you asked. 🙂

Which is why I see this place as the Beatles of blogs. Just as the Beatles took an existing thing (the idea of some guys with electric guitars and drums) and elevated it to something we’re still passionately talking about sixty years later, you folks took a thing (the idea of an online discussion forum) and elevated it to something unique. That ain’t easy.

The point about empathy and sympathy is important. It’s easy to forget we’re obsessing over real people, not fictional characters. Sometimes fans come to see their heroes as bendable, posable action figures – “Make them play! Make them fight! Bump them together and make them lovers!” – and it’s certainly a fun game. Maybe that’s why it’s so shocking for fans when we suddenly and inadvertently encounter “stars” in the street or other public place: we realize they’re just… people! “And much shorter than I envisioned! And why wasn’t he smiling?”

I’ve always wondered why conspiracies around Lennon’s last moments never really took hold. I remember them bubbling around under the surface, but they never seemed to stick. I’ve never seen a John fan nod knowingly during a conversation about Dec. 8 and murmur “The real story never came out” or “Someday the truth will be revealed.” I think if MDC had been killed by police that day, or later by an enraged fan, more theories would have emerged.

I remember going down various JFK rabbit holes back in the day. I remember waiting with excitement for Oliver Stone’s movie to reach my local theater. But the problem I had with some of the theorists was that I’d believe everything they’d say about stuff I didn’t know about, but then when they’d wander into territory I was familiar with… their logic would unravel. I think my fever broke when Mae Brussell claimed the plane crash that killed the Big Bopper, Holly and Valens had been orchestrated by the CIA.

Great piece Michael. I think what you have stated is on point, and I respect you for being civic minded. We are not going to make it as a country if we can’t agree on facts. Where we are at right now attests to that.

I wonder if people who get caught up in conspiracy theories are people who are afraid. By that I mean, they don’t like unknowns. They want to be able to have answers to things because it makes them feel safer.

It would be interesting to do a study on what makes certain people susceptible to conspiracy theories.

On the topic of McLennon, I think for some, it’s a way to explain the breakup. It’s so painful, and seems like such a loss, that we want there to be an explanation. I myself, have never fully bought into the McLennon story, but I have read many books and articles trying to figure out why the Beatles (specifically John and Paul) broke up.

@Tasmin, thank you.

“…what makes certain people susceptible to conspiracy theories.”

“Conspiracy theory” is loaded language, and to the degree it’s loaded, it’s not helpful. It obscures what is going on.

We cannot address conspiracy theories effectively without acknowledging a simple truth: most of our lives, most of our actions, and all of our motivations, are hidden. Out of what is public, plus what we wish to reveal, we create a “public story.” And so public stories, whether they’re our personal stories, or the story of the country, or the world, are artificial. They are overtidy, clumsy approximations of reality, partial at best, and require mass agreement; this agreement comes from who receives power from the story.

A conspiracy theory is a story which has not been agreed upon by the mass, but binds together a smaller group hoping to get more power as a result of mass adoption of this story. The so-called conspiracy theory can be more accurate than the conventional narrative; that is, the public story agreed upon by the larger group. It can emphasize important things left out of the conventional narrative; it can be a salutary mental exercise. “Conspiracy theory” = “illogical” = “antisocial” = “destructive” is not necessarily so.

Who agrees with what story–and why–is the important thing, not the details of the story. When a not-agreed-upon story gains traction, the point isn’t to parse it logically—but to see what emotional work it is doing for the people who believe it. Usually you’ll find a real problem, or at least a powerful psychological need that the conventional story does not meet.

Michael, excellent post as always. I’ve been lurking here for several weeks and want to say how much I enjoy this blog and its rational, compassionate, thoughtful tone. That’s rare for blogs these days (and especially for comments sections), so thank you.

I definitely have thoughts on McLennon (and McCartney and Lennon’s relationship), but I’m not sure if this is the proper thread to post them on. For now I will say that I love their relationship because of what I see in it–close, passionate, nonsexual love between two men. As a person who values and desires a close nonsexual relationship, I see a lot of beauty and hope in this, and that’s why I’m so drawn to their story, and to theories about what happened between them.

Post away, @Erin!

I have several really close nonsexual relationships, including with an ex-writing partner, and I cannot imagine life without them. To the degree that our culture is sex-negative, it’s an interesting and probably salutary mental exercise to ponder if John and Paul had a sexual relationship; but that should not devalue or erase the close nonsexual relationship, either same-sex or mixed gender. One of my closest nonsexual relationships is with a woman, and as a straight man that has been revealing.

I only recently came across the term “romantic friendship”. What distinguishes it from any other close friendship? Holding hands? Love letters? Call me skeptical but to me it sounds like sexual attraction that social mores and inhibitions prevent someone from acting upon.

Erin, I think what’s meant by “romantic friendship” depends on a lot of things, including the era. For example, in the 19th century some women joined in “Boston marriages” that were more or less accepted by society, and the degree to which they did or didn’t involve sexual activity isn’t clear. What is clear is that the understanding of gender and sexual attraction was quite different a hundred years ago. What’s imaginable / what people understand about themselves is importantly determined by the categories that the society they are part of recognizes and reinforces.

Nancy, good point. Society was much different back then. I’ve studied a lot of those romantic friendships and Boston marriages because I find them fascinating (and would love to have one!), but I also don’t know our society today can truly understand what they were.

Michael, thank you for the encouragement! I’m honored to converse with such intelligent, thoughtful people.

@Michelle, it’s difficult to put into words but for me it’s a kind of tenderness and protectiveness towards someone I adore but don’t want to sleep with?

Michelle, if I may comment on what romantic friendship was/is–from what I understand, it’s basically friendship with an added element of romance that goes beyond what most people would consider friendship. So yes, holding hands, or other forms of physical affection that might seem exclusive to a committed couple; bed sharing; love letters; perhaps some kind of of priority and/or exclusivity, a commitment that is similar to a traditional romantic/sexual relationship. There might also be jealousy, wanting to be the other person’s #1 priority, etc. From the historical couples I’ve studied, there also seemed to be a sense of wanting to stay together/spend life together, even if they ended up marrying other people.

Of course, what romance actually is varies. As a person who has studied a lot about asexuality, I can say that one can experience romance without sex, but what exactly that means is up for debate, even in the asexual community.

@Erin, asexuality is fascinating to me because it’s so often left out of the discussion. 1% of people, according to a 2015 British survey, might be considered “asexual.” That’s a lot of people!

“People sacrifice real things, jobs and marriages and whole lives, on the altar of their obsession.”

This is the real tragedy. We’re seeing it with the Capitol rioters who alienated their families, were fired from or quit their jobs, and are still doubling down on Q-Anon. And we don’t really know what will happen when these true believers confront an event (Biden’s inauguration) that they can’t easily explain away.

As for McLennon, all I can say about that is that I’ve said my piece, in the “Friends and Rivals” post and the “Ethical Reflections” post. And that I’m really tired of talking about it.

More than anything, conspiracy theories — both the more and the less harmful — seem like emotional displacement to me. The DESIRE to believe is primary; the data is secondary.

In general I would agree with you; the emotional content of the conspiracy theory is the key driver. But it gets complicated very quickly.

Take UFOs for example. Do I “believe” in UFOs? I don’t have an opinion. A friend of mine once wrote a book about alien abduction; he began as a skeptic and ended as a (limited) believer. I trust his judgment, but it’s not my experience. There are unidentified flying objects; I don’t know if they’re alien-piloted crafts from other worlds or dimensions or whatever. They could be? People who say “that cannot be so because: science” are suggesting that we have reached some endpoint in our understanding of reality, and even a cursory glance at the study of history or science says these endpoints don’t exist. Just as they might say, “UFO-believers need, emotionally, for there to be a world of magic and aliens,” I might say, “So-called skeptics need, emotionally, for us to have figured everything out.”

Then there is the allied stuff, which I think is the opposite of outlandish. That the US Government has covered stuff up relating to UFOs is simply factual. That doesn’t prove anything but that the US Government controls information. And it certainly doesn’t prove stuff like QAnon.

This is the important mental balance to strike: to recognize that there is corruption, psyops, and hidden materials–that the public story is often partial, even when it’s accurate and well-meaning–without dismissing ALL public stories as lies designed to manipulate. As I said elsewhere in the thread, who receives power from a story is a tremendous key.

Good points, Michael. That the most prominent theory of this type that we’re dealing with right now is Q-Anon is undoubtedly coloring my reaction.

See my reply to @Tasmin — I think the inability of our polity to process the political murders of the 60s, to digest the truth of what happened and thus culturally resolve them — is the seed from which QAnon grew. Hence JFK Jr. in a prominent role.

Micheal you wrote, “who receives power from a story is a tremendous key.”

That fits with the Big Lie regarding the election being stolen. That benefits Trump and the Republicans.

But I don’t think the “John and Paul as lovers” theory fits. Who gains power from perpetuating that? I think that’s more of an instance of believing that fits some emotional need.

In that case, the power is with the (mostly third-generation, mostly female) fans who understand (and are thus close to) John and Paul in a way all us olds aren’t. I think it’s harmless, because that’s a harmless kind of power; it’s just personal at this point. You see something generations of fans before you missed; okay, maybe so, probably not, but sure. There is ALSO an emotional need in it.

To destroy an old story is a demonstration of power within that realm, and a test of power. Who gets to tell what story? For example: most Boomers always believed that JFK/MLK/RFK were killed as the result of conspiracies. They had enough political clout to get a House investigation, which concluded probable conspiracy in the case of JFK, but not enough power to take that next step and achieve measurable political change as a result. So things reverted quickly to the old story, the thoroughly discredited Warren Commission narrative that served other groups, and demonstrated their power.

There was no one inside the government who benefitted from the JFK conspiracy story, so it died. If Teddy had been the Dem nominee in 1980, things might’ve been different. Things became different in the early 90s, with Clinton in the White House and Stone in the movie theaters, but in the end, nobody benefitted enough from the murky, unsatisfying truth for the manifestly untrue official story to be swept aside. But truth denied mutates, and I think that’s to some degree why we have QAnon, and why it appeals to Boomers so intensely.

Similarly: the Lost Cause replaced the actual narrative of the Civil War because that story served entrenched power; they simply had to wait out Reconstruction, and then the pro-South, anti-African-American story became the official narrative. But if there’s ever a conspiracy theory, it’s the Lost Cause. Powerful emotional need (“our cause was just because we’re good people”) and powerful constituency (racists).

The problem with labelling ‘McLennon’ a conspiracy theory is that you run the risk of driving away contributors who might have interesting and thoughtful points to make but daren’t do so in case they are made to feel stupid. It seems almost like an own goal for a site like this to stifle debate in that way.

And really, it depends what you mean by the word, ‘McLennon’. To me, it seems clear that John’s psychological disintegration was directly linked to the disintegration of his relationship with Paul, and the replacement of Paul (who loved him, but couldn’t cope with him) with Yoko as the person he relied on. That obviously conflicts with the official narrative, but does it make me a ‘McLennon’ conspirator, or do you have to believe they were lovers for that? What is ‘McLennon’ and what part of the John and Paul story is it reasonable to express an opinion on before it becomes a conspiracy?

The problem with so much of the debate about the Beatles is that the official narrative is regarded with a sort of reverence. Anyone who challenges it, even people like May Pang or Fred Seaman, who were actually there, are dismissed as unreliable for having ‘ulterior motives’. In the end, this only benefits Yoko and the Lennon estate, and it does a terrible disservice to the rest of John’s family.

Good point about what “McLennon” actually is. I hesitate to say I believe in such an idea, because it lumps me in with people whose ideas I don’t necessarily agree with (and, I feel, make me less likely to be taken seriously). But, I’ve found, there is not (as of yet) a better way to describe what I think about Paul and John’s partnership. There’s a closeness there that isn’t explained by our English-language terms like friendship, or close friendship.

As for conspiracy theories–I think there’s often a bit of truth to them, buried beneath all the hype and exaggeration. But I don’t think I’m qualified at all to say what is true and what is not, even if I do tons of research.

‘McLennon’ is a theory. Not sure it fits the definition of a conspiracy theory. I don’t think people who entertain the idea of ‘McLennon’ believe there is a mass coverup or that they’ve been lied to, and even if that’s the case they respect their reasons for doing so.

“The other night I was at a party, and we were talking about certain great events that shaped the lives of people my age. The emergence of the Beatles and the Vietnam War were obvious influences. And I said that I thought the assassination of Kennedy was a big influence—and as soon as I said that it I corrected myself. Oswald’s death was more an influence than Kennedy’s. Had he lived, so much more would have come out. His death left us a legacy of suspicion and doubt that’s turned in on everybody. It’s unusual. Such a neurotic little man, who was really such a loser, you know, and he’s left a very profound influence. The country would have recovered from the death of John Kennedy. But it hasn’t recovered yet from the death of Lee Harvey Oswald and probably never will.”

– Bob Dudney, Dallas Times Herald reporter

I think there’s some truth in the larger point, but what I’d say to Bob is this: “Oswald’s death” is a peculiarly passive construction here. Oswald didn’t die of natural causes after an inconclusive trial; he was murdered before trial, while in police custody, by a pal of the Dallas Police Department who was neck-deep in connections with the mob. It’s not Oswald’s death that caused all the suspicion and doubt — it was the precise circumstances of his death, and then later the precise circumstances of his life, that sowed the suspicion and doubt.”

Here’s what I never understood:

People who believe Oswald was the lone gunman (no wider conspiracy) always tell me that he was just a little man who resented JFK’s power, and wanted to make himself an influential part of history. Every time I express doubt about the official Warren Report story, I hear that same line, that Oswald wanted to make himself important.

But if this is true, then why did he insist again and again that he was just a patsy? If the “little man who wanted fame” theory is correct, then he should have been yelling “Hell yeah I killed him, and I’d do it again!”

Yes, I agree with you Sam. One of the central problems of the Warren commission is that it never creates a believable, consistent Lee Harvey Oswald.

Why,if he’d just shot the President, did he go to a movie? Why hadn’t he made any plans to escape beforehand?

(Because, I think, he was meeting someone. I think he was in the lunchroom, as several witnesses said, and was flipping out. As an fbi informant (admitted) and participant in CIA’s planned defector program (likely), a meetup would make sense. As a guy who just shot the President, it doesn’t…unless he’s a total disorganized mess, in which case it’s very unlikely he could do something difficult.)

Btw, everybody: note the tenor of Sam’s and my discourse. Utterly unlike QAnon, and other such nonsense. Beware of lumping all alternative history as “conspiracy theory.” Much is; some isn’t.

To me, one big distinction between a responsible discussion of “alternative history” and a deep dive into “conspiracy theory” is the emotional charge involved. When people seem to NEED a particular narrative to be true — and when they appear to be deeply invested in explaining a lot of data away to do so — that’s when I get uncomfortable.

I think an important question to ask ourselves is “How much do I want this to be true?” or “How much do I want this not to be true?” and work to be honest about what we’re up to.

Sure, but at the same time, we should also be equally able to see the needs of the institutions involved. It’s very easy to say, “Well, I want there to be UFOs for [reasons], so I’m biased.” That’s a much easier world to live in than the other side of the coin, which is, “Well, I know governments lie to us constantly and control information for their institutional benefit and the benefit of people inside them.” That’s also true.

About ourselves, we have as much data as we can bear to excavate. In my case, I can tell you that as a person born in 1969 to an Irish Catholic family active in Democratic politics, the Kennedys (and MLK) were our household gods. But that only predisposed me to be interested in the Kennedys (as my nephew is, a generation later). What caused me to be interested in the facts of their murders was just that: the facts of their murders. Both that they were murdered — hmm peculiar — and that the official stories of both murders are at best infernally complicated and at worst complete whitewashes.

Actually, that’s not quite all: my father died when I was young, under some murky circumstances. AHA, right? Well…only if there are murky circumstances. There is no good reason that the JFK/RFK narrative should be loaded with spies, but it is.

It is easy for us to believe the national myths, of Camelot, of “the Kennedy Curse.” It is more difficult for us to acknowledge that

1) American rightwingers were terrified of a Kennedy dynasty, because it was a way around their attempts to prevent another Roosevelt. JFK until ’68; RFK until ’76; Teddy until ’84. And that’s all she wrote for conservatism and the GOP. Was that likely? Maybe not — but it’s what they openly feared, and spoke of, in 1961-63.

2) American rightwingers and their fellow-travelers in the military industrial complex were (and are!) all too willing to use violence to circumvent democracy.

3) Violence has been applied unequally in our society, as it was during the run-up to the Roman Civil War. Violence has really only struck people looking to reform within the system, and so the things that need to be fixed remain unfixed until they eventually explode.

4) In addition to the assassinations, you have Teddy’s plane crash in 1964, which he escaped by a hair’s breadth; and Chapaquiddick which some people suggest wasn’t as simple as it seemed. It was–like the assassinations–exceedingly convenient for one political side.

So while we interrogate ourselves (I was predisposed to be interested), we must also interrogate reality and politics (that the violence all seems to benefit the Nixon-Bush wing of the GOP). This this last is never really addressed by the intellectual gatekeepers of society. Since they won’t, we have to.

Michael, I agree with you in essentials, I think. Certainly I think we need to be critical thinkers and ask who benefits from particular narratives.

It’s when we get to the explaining away data part that I get especially concerned, since it’s so easy to adopt a conclusion and then pick the “facts” that support it. Hence the Q-Anon exhortation to “do your own research” comes with the unstated addendum “as long as it supports the current Q-Anon line.”

The problem here is that the internet provides too much data, and pushes a narrative that “my ignorance is just as good as your expertise.” Data is not the problem; it’s judgment.

“A conspiracy of silence speaks louder than words.”

– Dr Winston O’Boogie

Indeed O wise one

@Nancy, I agree 100% with this:

“When people seem to NEED a particular narrative to be true — and when they appear to be deeply invested in explaining a lot of data away to do so — that’s when I get uncomfortable.”

That seems to be the case with most hard core Trump supporters.

In regards to the Beatles, I once got into an argument on the Washington Post comment boards, on a story about the Beatles. (This was a few years ago) I mentioned Yoko introducing John to heroin, which led to an argument about Yoko being a good person, who is unfairly demonized. As has been discussed here before, Yoko is a polarizing person, and there are fans who insist that the “Ballad” narrative is true. It’s fruitless to argue with them, because they believe what they want to believe.

‘Yoko is a polarizing person, and there are fans who insist that the ‘Ballard’ narrative is true. It’s fruitless to argue with them, because they believe what they want to believe.’

Exactly. If you ask me, it’s the ‘Ballard’ that’s the conspiracy theory – misinformation and propaganda sold as truth to the gullible.

It benefits Yoko, and Paul to some extent. But I’m not surprised by how much it has messed up Julian’s life. If I was him, I would never be able to forgive or get over it.

Yes, Julian has every right to be angry and not forgive. I did hear an interview with him last year on The Beatles Channel (SiriusXM). He said he forgave Yoko because of Sean. He wanted a relationship with Sean, and it was important to him (Sean) to forgive her.

I also think Paul forgave Yoko for 2 reasons: 1. Business 2. Before George passed, he encouraged Paul to forgive her for his own mental and spiritual health.

JohnandYoko is a religious belief.

Just have to add that I also agree with this part of your comment Nancy,

“I think an important question to ask ourselves is “How much do I want this to be true?” or “How much do I want this not to be true?” and work to be honest about what we’re up to.”

I admit I am guilty of not wanting to believe anything bad about Paul. He’s always been my favorite, and if I hear something not flattering about him, I get defensive for him.

Granted, he’s a pretty non controversial person, but like you said, I have to ask myself how much I don’t want to believe anything negative.

Tasmin, I agree that it’s challenging to put aside our emotions when we’re dealing with negative information about someone whose work we care deeply about. As a McCartney fan, I’ve now mostly made my peace with acknowledging that he can be dopey (“Fuh You,” ugh) and oversensitive to perceived slights (his prickliness in some interviews when he faces hard questions). He’s got his faults, for certain. I think the trouble starts when we need someone whose work we esteem to be beyond reproach, because no one really is.

I’m just grateful that neither he, Ringo, or any of the Beatles kids or spouses is apparently doing anything actually destructive, like, for example, campaigning against masks and other covid mitigation measures (looking at you, Van Morrison and Eric Clapton).

Well said. I am happy that the Beatle kids seem well adjusted and socially conscious. Ringo and Paul are basically decent people. And mortal.

Yeah, what is up with Morrison and Clapton? I know Morrison is a curmudgeon, and not a very nice person according to Graham Nash. But Clapton?