- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

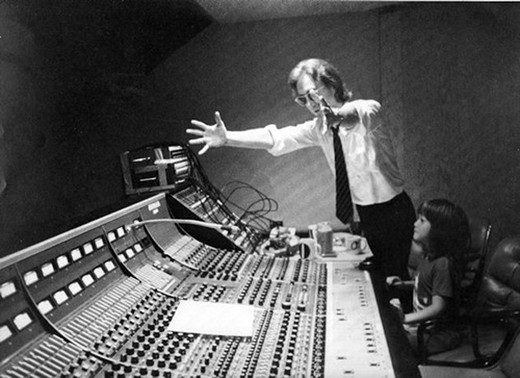

“Someday, son, this will all be yours. If you have Garage Band.”

I am always trying to figure out a non-obnoxious way to spotlight some of our great old posts. (There are over 600.) Today, commenter Damon F. solved that problem for me by finding this impassioned burbling on “Harry Nilsson: The Shadow Beatle“, which spurred him to burble the following in response:

“I think it’s a bit unfair to say Lennon squandered his gifts considering he was shot dead at age 40. He worked five years post Beatles yet is compared to the others who worked much longer. All indications were the 80s would have been a very good time for Lennon, the times would have finally caught back up to him as it were. Kind of hard to see him going wrong with guys like Andy Newmark, Tony Levin, Earl Slick, etc, on his team.”

What an interesting launching point for a discussion; thanks, Damon. I don’t think I said that Lennon “squandered his gifts,” exactly; more that his chemical addictions subtly but steadily wrecked his creative mechanism — as it did for Harry Nilsson, the subject of the post, and Peter Cook, Lennon’s one-time friend and authentic comedy genius. And furthermore that recognizing this self-sabotage is so painful for us that, after it’s done its work and the person is dead, there are always apologists ready to spin the addiction into something more palatable. But before I revisit that point, let’s address your point about Lennon in the 80s. Here’s my take:

I think judging John Lennon’s solo work simply in how it stacks up against the solo work of the other Beatles sells him short. If he was a genius, as he endlessly claimed post-Yoko, then that’s a much more rigorous standard — but it’s one that he would likely accept, maybe even insist upon. Interesting, proficient, even enjoyable work — none of these are sufficient for genius. They are merely starting points. And it’s no longer about where a piece of work fits into one’s personal development, but that PLUS how it is received by his/her peers, PLUS what impact it has on how the art is practiced, PLUS how it lives in the culture at large. The difference between wonderful work and genius is the difference between “Leave My Kitten Alone” and “Tomorrow Never Knows”, or “Dr. Robert” and “Strawberry Fields Forever”.

Singers use microphones. Geniuses use mics in milk jugs filled with water, with condoms on them.

Much of Lennon’s Beatles stuff clears this bar, and any other bar you care to set up. But with the exception of Plastic Ono Band, and perhaps the song “Imagine,” his solo stuff does not. After ten years and ten albums, we knew the parameters of solo Lennon. Thirty more years in the studio with great sidemen probably wasn’t going to fix John Lennon’s flaws — his susceptibility to fashion, his dearth of musical ideas, his impatience (weaknesses that, when balanced by others in the Beatles team, were often strengths). John Lennon was a formed artist. The only thing that possibly could have provided a quantum leap for Lennon in the 80s was working with Paul again, because that’s where the genius had always been, John&Paul, and not just John or Paul. The stuff with Cheap Trick is a fun listen, but it’s not genius. Ditto “Walking on Thin Ice.” Interesting, proficient, enjoyable, but we gotta blow away these myths. If not us, who? If not now, when? I know you want to go get some Gummi peaches, but we can’t leave it for the next generation. They’ll all probably have chips in their heads and sext in ones and zeros. Screw them.

The first myth that we must explode is Lazarus-in-Bermuda; “The Dakota Beatle Demos” shows that Lennon had been composing during his retirement (in the bug-crawling-across-the-kitchen-floor manner in which he worked in the post-Paul years), and that it took him a solid five years to come up with the Double Fantasy/Milk and Honey material. What happened in 1980 was that he wanted to play the game again, not that his muse had returned. That was self-protective spin.

The second myth is that Double Fantasy is genius Lennon, a major artistic statement; it isn’t. Pre-assassination, Double Fantasy was considered a bit of a damp squib — pleasant, catchy, somewhat interesting within the rock idiom for its celebration of hearth and home. But nobody was calling it Great Art, nor was it a massive worldwide smash, until after Lennon’s murder. That event gave every note of Double Fantasy a power and pathos that it does not possess alone.

It would be as if the Beatles plane had gone down during the ’65 tour. The Shea Stadium concert would be as mythic as Double Fantasy, and that version of “I’m Down” would be as mythic as “Woman” or “Watching the Wheels.” But that wouldn’t make it a better song, and it wouldn’t make John playing the keyboard with his elbow into Great Art.

Now I must admit something to you: As an Irish Catholic I grew up surrounded by a haze of What Might Have Been, from JFK to last Sunday’s burned roast, and I’m allergic to it. So allergic that I might overcompensate. But I’m sticking by my guns on this one; the LP and singles had been released and reviewed. It was only after Lennon’s horrific death that the Double Fantasy stuff took on the mythic weight it has now. And how could it not?

But like I said, predicting the course of John Lennon in the 80s wasn’t really what I was getting at in that earlier post. My point –expressed better there, go read it — was that geniuses with chronic addictions seem to exhibit a similar career arc. In The Last Tycoon (his own version of Double Fantasy) F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote “There are no second acts in American lives.” I think what he really meant when he said “American” was “addict.”

Fuck you guys

Geniuses are delicate machines. A genius with a decades-long habit is like an electron microscope after the raccoons got to it. It is an exquisite tragedy that it all happens so quietly; the body and brain seem fine, living on long after the genius has been driven from the tissues by poison — and nobody feels this absence more acutely than the artist him/herself. The hunger to reclaim that genius is what drives the artist to the One Last Effort, and our own hunger supplies the What Might Have Been.

Is this just a story structure? Could be. But it also makes sense to me that this course is biologically determined. Initially, an individual’s young strong brain and body can process whatever is ingested — and indeed the chemicals seem to enhance the creativity. In youth and strength, chemicals are a tool the genius uses, going places others can’t/won’t go. Over time, however, the liver and kidneys and brain deal less and less efficiently with what you’re putting in them, and the deleterious side-effects are felt more and more strongly. The artist’s lenses become clouded, his/her subtle mechanisms of perception are nudged farther and farther off true. “You let the raccoons in on purpose?”

For Lennon in the 80s, or Brian Wilson post-SMiLE, “good” takes supreme effort; “great” is an impossibility. It is only our sentimentality — our love for the artist, and ourselves — that makes us round up that final bit of work. There’s no harm in it, as long as we also acknowledge that, y’know, drugs wreck you even if you’re a genius. Of course they dull you and slow you and warp you — that’s why human beings take ’em.

Of course as long as Lennon lived, there was the potential for him to return to the creative heights of his Beatles years. Whatever raccoons do, people can fix, I suppose. It’s lovely to think that the 1980s would’ve been a renaissance for John Lennon. Let’s think that, since we can’t have the man himself. But I will also curse the raccoons.

Michael, I think you ‘re right about the raccoons. ‘Grow old with me’ is a wonderful melody and a little too obvious lyrics, and belongs to Lennons best work. You dismiss ‘walking on thin ice’, can you tell us why?

You put forward a few conditions that make an artistic work the work worth of a genius.

First I think forget the artist, it is about the art, that makes a work worthwhile. So whether a piece of work fits into one’s personal development is utterly irrelevant. A piece of art can be very important in the artistic, creative or personal development of an artist but have no resonance with current audiences or artists, what if it is just ugly but presenting a new technique, point of view or new way of communication?

I think your criteria are too much context related and less related to the piece of art.

If anything could be said about the genius of Lennon’s work, the peace marketing was gorgeous and work of a marketing genius within his branch of art, and still stands out and had and has a huge influence on other artists. That we are less include to serve peace is because today we have forgotten about respecting and accepting diversity in thinking and feeling and behavior, we are rotten to the bone in that we believe we are right. Paul did the oppositie with his populist in God-given-right(for)freedom. Following Bush and Putin in their religious war-mongering is simple ingenious behavior, Lennon was and is up there, no other artist after him has surpassed this stroke of genius.

Oh yeah, and you might not like to re-listen to the Plastic Onno Band album, but that doesn’t make it mediocre, the darkness ans nakedness of the music and the words, whether they are autobiographical or not is unimportant, stand out – genius and influential.

Rob, I agree that Lennon & Ono’s peace promotions continue to have an enduring influence and are an important part of Lennon’s legacy. He deserves to be honored for them.

On the subject of McCartney’s song “Freedom,” I think you and I have commented on it before. As I said then, I think it’s a crappy, simplistic song. But it is inaccurate to say that McCartney was “following Bush’s war-mongering.” He wrote it in New York City, the day after the September 11 attacks, which he witnessed from the airport — before the U.S. declared war with Afghanistan or anyone else.

Here’s some more context, from this source:

“McCartney, who said the attacks affected him emotionally, wrote the song the day after the attack. In the song, the narrator declares freedom to be a “right given by God” that he will “fight for.” The lyrics were thus in seeming contradiction with the antiwar sentiment associated with McCartney’s former act, The Beatles. But at The Concert for New York City where he first played the song live, McCartney explained to the crowd, “It’s about freedom. That’s one thing these people don’t understand. That’s worth fighting for.” In a later interview McCartney commented, “to me it’s a ‘We Shall Overcome.’ That’s sort of how I wrote it. It’s like, ‘Hey, I’ve got freedom, I’m an immigrant coming to America, give me your huddled masses.’ And that’s what it means to me, is, ‘Don’t mess with my rights, buddy. Because I’m now free.’

McCartney performed the song on his 2002 Driving USA Tour and it appeared on the live album Back in the U.S. However, he chose not to perform it on subsequent tours, such as his 2005 The ‘US’ Tour, as he felt the song had acquired a militaristic meaning with the Bush administration’s Operation Iraqi Freedom. In an interview, McCartney stated: “And I thought it was a great sentiment, and immediately post-9/11, I thought it was the right sentiment. But it got hijacked. And it got a bit of a militaristic meaning attached itself to it, and you found Mr. Bush using that kind of idea rather a lot in [a way] I felt altered the meaning of the song.”

@Nancy, I’m reminded of all the right-wingers who listen to “Imagine” and accuse Lennon of stumping for Communism. As we all know, Lennon may have admired Communism as a theory, but in practice, there was no one less interested in forced egalitarianism, or living under a regime empowered to tell him what to do. Lennon was 1000% a Western capitalist; and you can tell because, when he had feelings of egalitarianism and brotherhood, he turned them into something he could sell.

I put “Freedom” in the same bucket; terribly easy to misunderstand, and best enjoyed as an expression of a set of feelings, not as a part of a larger, well-thought-out political narrative or philosophy.

I agree with your description of Lennon 100%, and really like the concluding argument, that he found a way ‘to sell’ peace – the conclusion he had “feelings of egalitarianism and brotherhood”, I can’t find in the autobiography, he may have had political thoughts, but an emotional deeply felt connection to ‘egalitarianism and brotherhood’ I don’t find in his biography, nor his art.

.

To me peace is not related to brotherhood, nor egalitarianism… Any suggestions to where we can find these ‘feelings’ in his art and biography?

@Rob, I think you need go no further than the lyrics of “Imagine” to witness Lennon’s feelings of brotherhood and egalitarianism:

“Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky

Imagine all the people

Living for today…

Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people

Living life in peace…

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will be as one

Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man

Imagine all the people

Sharing all the world…

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will live as one”

The brotherhood’s explicit, and the egalitarianism is implicit. It’s impossible for any of this to happen in a fundamentally unfair, unbalanced world, and Lennon knew this. This world he’s describing is one where the primary drivers of conflict — greed, want, prejudice, vanity — have been lessened/eliminated; and yet he knew that so much of what got him out of bed in the morning were exactly these drivers of conflict. This push-pull inside John Lennon is the central driver of his adult personality. He’s wise enough to know what would lead to happiness, for him and the rest of us, but doesn’t yet have the self-mastery to achieve that. Sometimes he gets depressed and thinks it isn’t even possible.

I think he’s far from alone in this; it’s probably a tension faced by any reasonably thoughtful person embedded in our capitalist/nationalist/religion-soaked world. It’s the near-universality of this internal struggle that made Lennon so resonant then, and still resonant today.

@Michael https://www.heydullblog.com/1980/lennon-in-the-80s/#comment-162425 The concepts of brotherhood and egalitarianism were part of the political ideas John seemed to have been exploring without much dedication and adherence. He wanted to know and understand, never able or willing to surrender and change course like Harrison did – who took up the spiritual ideas and rituals and of course never stopped using the symbolism and stories inherent to hinduism.

.

‘Feelings’, however is a much deeper thing, Michael. There is emotion and the body involved, not just or merely thoughts. Feelings is emotions/physical sensations plus follow-up thoughts, I just guess Lennon never went that deep, neither with Imagine nor Give Peace a Chance. Of course he was able to create a state of mind to create and project out to his audience what he intended to and what fits the message and feelings he wanted to create within (among) us, so we buy and appreciate him, and make him even more famous…

.

… and then again, he knew his song was good, the artistically judge in Johnny boy was in perfect shape here, he knew he had something very nice and good in his hands. Of Imagine, I think he said in the movie to Nicky Hopkins was his favorite or most beautiful song of the lot he wanted to record for the album.

.

Feelings of brotherhood, dunno brother, I doubt it very much, you might wanna check out some of the early books of Damasio to understand how he was able to proof the intuitive concept of feelings with his neurological research. The somatic marker hypothesis etc.

Thx for the explanation, Nancy.

Do you have and references to the sources you quote – I am interested to understand the context of the quotes, as Paul McCartney only recently explained hoe meaning was put into the songs by others in ways that he only later understood were true to the song lyrics.

.

I advice to listen and look at the conversation Eric Clapton and Paul had before performing the song, the explanation smells of opportunity and populist entertainers motivation. Either he is a bragging performer in this conversation or did not compose the song on the day after.

.

The war-mongering I pointed out is related to “God-given-right(for)freedom” – the reference to God is from Paul, and totally fits the Bush and army thoughts and feelings – apart from the desire to project out military power to protect our way of living and thinking.

.

The God-reference (hiding behind religious backs?) lacks the humanistic sensitivity and smartness Lennon showed in matters of politics and peace. To believe that our kind of freedom as a GOD-GIVEN-RIGHT, is the right kind of sentiment on a night like that shows a level of ignorance of a great composer-musician-performer. Thank God I don’t believe in Lennon, in Dylan or McCartney but frequently highly enjoy their music – still.

.

You strengthen my interpretation by quoting McCartney: “It’s about freedom. That’s one thing these people don’t understand. That’s worth fighting for,” which he supposedly told the audience as an introduction to the song. My God what an ignorance, as if our interpretation of individual freedom is the holy grail and these people don’t get our concept of freedom? Silly underestimation of the political opponent, and part of dehumanizing the enemy, as Bush did and many whities still do.

.

Hope this makes little bit of sense.

Rob, I understand your opinion, and I agree that the idea of “God-given rights” has been used to justify terrible things. I’m just more inclined to interpret “Freedom” along the lines Michael suggested, as an expression of feelings in the moment. I don’t think McCartney thought hard enough about how what he was saying might be used.

Thx Nancy, if this should be true “as an expression of feelings in the moment” it is even worse. Musically the phrase ‘God-given-right’ has power, and the populist performer Paul loves that rocking feeling of the words, he tells Clapton he wants the audience to rock, and the music goads them.

So if the phrase ‘God-given-right’ is spontaneous, at least the religion issue was on Pauls mind and he thought this to be relevant… there is just no excuse for an artist like him. I think Give Ireland back to the Irish was better, but put under scrutiny the same kind of hesitation in appreciation is possible.

btw still wondering about what your sources of McCartney quotations are/were.

Rob, I’d be interested for you to expand of how John showed a “humanistic sensitivity and smartness in matters of politics and peace.” To me, neither John or Paul were very good at political songs. I agree that “Freedom” was a piece of crap, but Paul was never a followed a George W. Bush. He debuted the song before the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and actively disavowed it when he worried it could be seen as militaristic. Paul also turned down a Kennedy Center Honor when it was given by Bush, and though he can’t vote, actively supported Democratic candidates like Clinton and Obama (who his American wives did vote for). He also expressed views against John McCain to a reporter and was vocally anti-Thatcher.

Paul’s strength in social activism is with actions, not words. LIPA has been a great success in education and helping a new generation of artists. Paul and Linda also did more to mainstream and promote vegetarianism than arguably anyone, turning it from a hippe fringe diet to a valid and common choice and multimillion dollar force. Paul also has a long history of collaborating with black artists, even when it’s garnered him criticism from some circles, and he spoke about the recent police killings of young black men as well as the Charleston mass killing. As far back as 1966, in their Maureen Cleave profiles, Paul was the only Beatle to comment about the civil rights struggle.

If you want to talk about misguided, let’s talk about John’s only significant comment on black civil rights, “Woman is the N*gger of the World.” “Freedom” is merely a crime against taste, but John willfully misappropriated a word he zero right to use in a completely ignorant comparison that manages to denigrate both racial civil rights and feminism.

John also donated to the IRA (which means his money was likely using to maim and kill people) and advocated for convicted rapist and murderer John Hanratty (who was proved “beyond doubt” via DNA in 2002 to have committed the crimes that John, among other limousine activists, argue he was innocent of). John was anything but smart about politics, and even acknowledged that he was often taken in by militants (such as John Sinclair) he shouldn’t have been, because they prayed on his guilt.

We can never know what John’s political evolution would’ve been, but people willfully ignore his disavowal of his early 70’s militantism, his lack of commitment and tendency to follow the “cause du jour,” and the indications that in 1979-1980 he was expressing more conservative views, including admiration for Ronald Reagan. Reagan conservatism would of course because the political movement of the 80’s, and I could definitely see an older (and no longer risk of being deported) John going with the flow, as he did so many times.

@Rob, I didn’t call Plastic Ono Band mediocre; I in fact said that it — and perhaps the song “Imagine” — were the only post-Beatles Lennon that I consider to be genius. Can’t praise something much higher than that, even if (as you rightly recall) I listen to POB very seldom.

Similarly, I don’t dismiss “Walking on Thin Ice.” I say it’s a nice piece of work — which is given extra prominence for having been the last track Lennon worked on, the tape he was carrying when he was shot, etc. That doesn’t make his solo any less cool; but it does point out that, in that case, context is probably driving the lion’s share of our opinion, not the work itself.

You and I disagree on this, but I think it’s impossible to appraise a piece of contemporary art outside of its historical context. So I think we should factor it in. It’s impossible for us to hear Double Fantasy as it was heard on December 7th, 1980; and attempting to is outfoxing ourselves I think.

John and Yoko’s Peace Campaign — and I think you MUST include Yoko in this, given how it’s so much more in her previous idiom than in her spouse’s — is certainly noteworthy for a lot of reasons, but IMHO the passage of decades has found its central premise flawed. Turns out you can’t “sell peace like soap,” because peace isn’t a product that you can buy. It’s something much more profound, a state of being, and in its reduction to a catchphrase something essential doesn’t come across. The “peace” in the Peace Campaign is like the “love” in “All You Need Is Love” — never quite defined, nor is the audience told what to do. A soap commercial is a totally different thing: “There is this particular object, and you should buy it, for these reasons.” The reasons can be conceptual — happiness, hipness, etc — because the other parts of the advertising model are super-concrete.

So the Peace Campaign was very effective in putting forward a narrative — “War is over if you want it” — but that narrative was fundamentally conceptual: which war? Over means what? Want it how? Are John & Yoko advocating absolute Christly pacifism? Gandhian, politically astute non-violence? Buddhist nonharming based on the concept of reincarnation and interbeing? Or are they simply saying “US out of Vietnam”? I rather think it’s the last one, but saying that seemed uninteresting and likely to cause even more hostility. But whatever your reasons, you can’t leave that stuff up to the audience, especially if you’re trying to sell something.

War is very concrete, and only concrete solutions seem to reduce it. I don’t know of a single war that has ended as the result of a massive change of heart — it’s the difference between the 1914 Christmas Truce and the Treaty of Versailles. Nothing wrong with the Peace Campaign, I don’t think it hurt and maybe it helped, but as activism Bangladesh was more effective, because it was a concrete, well-defined solution to a concrete, well-defined problem. Was the world more peaceful in 1969 because of the Peace Campaign? Impossible to say. And in the years since? Who knows? I’m glad they did it, sure. But John & Yoko began from the premise that war’s primary cause is habit and bloodlust, and they weren’t wrong; but to address the thinking without addressing the conditions that cause the thinking (what’s causing the fear, hunger, poverty, resentment, hunger for glory) is at best peculiar and at worst foolish. Well, actually, worse than foolish would be something that distracted people from more concrete political/social action, and it’s entirely possible that the Peace Campaign did that. Or maybe it was totally benign. Impossible to say.

Rob, I cited the website where I found the information — if you want to do more research on this, please do and report back. I’m not inclined to give “Freedom” any more attention, myself.

I think all McCartney’s general “issue” songs are pretty lame — “C’mon People,” “Peace in the Neighborhood,” “Looking for Changes,” etc. It’s not his strength at all. I think he makes useful societal observations only when they’re very strongly grounded in empathy with individuals (“Eleanor Rigby,” “Another Day,” etc.).

Lennon wrote much better issue songs, no question.

Ok, case closed, quoting secondary sources is too risky for me. Questioning and verifying credibility of sources for quotes from ‘famous people’ is key in weighing arguments.

Rob, what I meant is that I don’t think this song warrants this level of analysis. I believe the website I cited is credible on this subject because the quotes accord with what I remember reading elsewhere in an interview with McCartney about regretting the way the song was taken up later. I am not trying to close any case, or saying that I have proven you wrong.

Edited later to add: But you make a fair point about needing to fact-check sources, so I went searching and have pasted in the source below.

The quotation that’s not from the concert is from this Pitchfork interview from May 21, 2007 (you have to scroll down for it). More of the context below.

Pitchfork: I wanted to ask about the song “Freedom”, which you wrote in the wake of 9/11. Lately dropped it from your setlist. Do you think it might come back?

McCartney: I’d very much like it to come back, because to me it’s a “We Shall Overcome”. That’s sort of how I wrote it. It’s like, “Hey, I’ve got freedom, I’m an immigrant coming to America, give me your huddled masses.” And that’s what it means to me, is, “Don’t mess with my rights, buddy. Because I’m now free. I used to live in an oppressive regime, I’m from Sierra Leone, but now I’m an American, and don’t try to take that away from me.”

And I thought it was a great sentiment, and immediately post-9/11, I thought it was the right sentiment. But it got hijacked. And it got a bit of a militaristic meaning attached itself to it, and you found Mr. Bush using that kind of idea rather a lot in [a way] I felt altered the meaning of the song.

But it was great on the tour immediately post-9/11. It was great to sing it for the American people. It was great for us, it was very healing, it was very, “Stand up and be counted.”

Pitchfork: Even at the time, some people thought it was uncharacteristically militant.

McCartney: That’s true. [But] it was not militant. It was written from the point of view of, as I say, someone coming from a repressive, like let’s say, European Jew coming to America. He just got away from Hitler. That kind of thing. Or that– in all its forms. That particularly happens in America. It happens here in the UK, but America I would reckon is global target of people escaping oppression.

Pitchfork: It’s almost like we lost the word “freedom” because of Bush.

McCartney: Well, I think that’s kind of what happened. I think it did– yeah. But I may tour America next year, I’d like to, and I am wondering whether I can sing it again. Because it certainly was very popular. But I don’t know, I don’t know.

It was very flag-waving. And in the wake of 9/11, that was sort of a good thing, because American spirit was in danger of being squashed. And I knew a lot of New Yorkers, for instance. And I knew a lot of people who would write to me and say, “I’m never going to go on an airplane again.” And for Americans to say that … but then I did a concert for New York, the 9/11 concert, that I was part of, and I got a message from some woman in Boston saying, “I’m coming to this concert, and you’ve really helped me. Because I’ve got to get on an airplane.” And there was this feeling of healing going on, you know. That somehow me and some other Brits were able to stand up and say, “Look, you know, this– you will overcome this.” And it was a feeling that we should try and help.”

And I was in New York the morning of it. I was at Kennedy, I was just about to take off, at Kennedy Airport. And then the airport closed, and I could see the Twin Towers out of the window of the airplane. And so I was then sort of stranded in America for a couple of weeks while the whole thing unfolded. So you know, I was very much in the area. And everyone was scared, man. There were rumors it was going to happen again. It was a very scary time. And a lot of people wouldn’t move, a lot of people were just too scared to do anything. So “Freedom” arose out of that. It was to try and help that, to try and unscare people, try and remind people, “Hey, this is my right, man. Don’t mess with me.”

I tend to think that John squandered his gifts–first by kicking Paul to the curb, and second by choosing Ono as Paul’s replacement.

Paul always says that he feels John’s influence every day, hearing his voice yay or nay his creative choices. I’m sure John felt the same way, but resisted the voice in his ear–to his eternal creative detriment.