- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

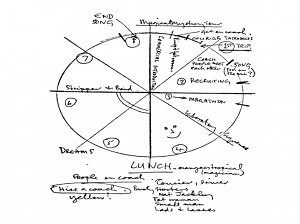

Magical Mystery Tour pie chart, 1967

This blog seemed to go through a phase where every second post was about how awesome Ram was/is. Go back and check the stream; it was amazing. Went on for months. And I support that, not just because Ram is awesome, but because this ol’ world of ours is big enough to have one place where Ram-love flows freely, without fear.

In that same spirit of being just bleeeaaagggrhhh…without in any way demeaning the White Album!—I present the following.

This evening while trying to avoid doing my wife’s Bialetti pot, I read this Slate review of the documentary “Magical Mystery Tour Revisited” (posted on Dullblog here), and bashed out a comment. Upon my usual obsessive re-reading and editing, this screed seemed too ur-Dullblog to waste on Slate. Slate‘s motto should be, “Our commenters hate everything. Slate, its editors, this article, but most of all, each other.” Slate isn’t a magazine, it’s a cyber-thunderdome for the underemployed. Not that I’m judging. I aspire to mere under–employment.

So, here’s me:

A flop, or the first “Midnight Movie”?

“Forrest Wickman seems weirdly hedgy in this review of Magical Mystery Tour Revisited, as if he’s reviewing something he doesn’t really want to talk about, or doesn’t want to admit how much he doesn’t like it. Maybe he’s a Gen Y-er with a low tolerance for what he thinks might be hippie bullshit; that would make sense. “This movie sucks. But then again, it is The Beatles, and Scorsese likes it, so here’s a review of this documentary.”

I’ve watched the doc, and IMHO it’s solidly worthwhile. True, MMT the film isn’t very accessible, but there are reasons for that, and they are interesting. (Well, interesting enough for a piece on the internet. You’ve been warned.)

Magical Mystery Tour marks the first time since the 1962 Decca Auditions that The Beatles weren’t surrounded by any of the topflight collaborators that helped shape their output. On the music side, they had George Martin, who we can all agree was a perfect fit (just listen to what Dave Dexter Jr. did to the early US records if you need convincing). On the non-musical side, The Beatles’ standard MO was for Brian Epstein to hire a young, hip, yet established talent like Dick Lester (AHDN and Help!), Alan Owun (AHDN), Joe Orton (aborted), Peter Blake (Sgt. Pepper), Richard Fraser (ditto) or Heinz Edelmann (Yellow Submarine) to ensure that all Beatles product maintained a high level of competency and professional gloss. This then allowed The Beatles to concentrate on the music, the music to shine through, and their personal charisma to take hold…with the downside being (as in Help!) a sense that John, Paul, George and Ringo didn’t have much to do with it. (Lennon was particularly acid about this later, but he seemed to forget that the alternative to Help! was Having a Wild Weekend. Just as he forgot that the alternative to “having to put on fucking suits” was “getting a job.”)

Whenever Beatle product wasn’t under Epstein’s eye, icky things happened, even to the music, which one might think would be impervious. Compare the UK LPs with the American ones: major or minor, the UK ones are stylishly packaged and sensibly sequenced, whereas the Capitol cash-grabs like Something New or Beatles VI or Beatles ’65 or Yesterday and Today somehow reduce the greatest group in rock history to Liverpool’s version of Herman’s Hermits. Brian’s eye for the right collaborators was a huge part of the group’s success, and how the five of them leveraged that success into more and more control, is the breakthrough that allowed the entire second half of their story. And also, what drove the group apart.

MMT was the first departure from the successful method, but it was largely an unwilling one. Though Brian died in August of 1967, The Beatles were already so established that control was no longer a question—the BBC approved Magical Mystery Tour sight unseen, just as Abbey Road now let them record past 10pm and EMI spent “princely” sums on their sleeves. But the group didn’t just jump to a bigger-and-better manager, like Robert Stigwood; they went DIY. That’s huge in 1967. It is, dare I say, punk, if in the most Beatle-y of ways.

That’s the good news. The bad news (for The Beatles, at least) is how MMT really cemented Paul’s dominance of the group’s direction. Though they were nominally managing themselves, Paul’s desire and ability to handle the details made him the group’s creative driver, precisely when that title meant more than ever. Because they no longer had an external enemy to defeat—because The Beatles could truly do whatever they wanted—each member began moving in his own direction. Brian’s death and Paul’s ascension are two sides of the same tragic, inevitable coin. Sgt. Pepper‘s creative unity is so strong it doesn’t even have to have a concept to become a concept album; MMT‘s creative disunity is so strong that even some of The Beatles’ best songs can’t stitch it together. The strengths and flaws of MMT are the strengths and flaws of the post-Brian Beatles, and for that alone, the film and documentary are must viewing for fans of the group.

Like their soon-to-be launched record label Apple, MMT is The Beatles making it up as they go along and, like Apple, it’s authentic and revealing even when it’s half-assed. Also: There is a side of The Beatles which is essentially comedic, and you see that clearly in MMT. And of course one can (and should) look at MMT within the context of the experimental art/filmmaking that McCartney especially was hoovering up. Wickman’s on the wrong track when he compares MMT to Head—Magical Mystery Tour is not ironic, cynical, detached; it’s not about the alienation of being famous or the distortions of media; it’s not The Beatles through the lens of Nicholson or Rafaelson or anybody but their own weird, switched-on, music hall, Goon-y, ration-raised, English selves. MMT‘s a home movie, and worthwhile (or not) for the same reasons. To compare it to a young Hollywood film is to miss the point entirely.

Nor was it a “head” movie like 2001—though it probably should’ve been. The movie was only a failure because it was broadcast to the wrong audience under the wrong circumstances. If it had, for example, been released via exclusive showings at the very-much-alive Brian Epstein’s Savoy Theater, and then shown in America at the Fillmore East and West, we’d look at it totally differently. Not The Beatles’ first flop, but the world’s first midnight movie. If Brian had lived, I suspect the final product would’ve either been more polished, or psychedelically dog-eared, but released in the right way to the right crowd.

Then there’s the music, which spans what is arguably The Beatles’ most interesting, most creative, most cohesive year (Nov. ’66 to Nov. ’67). So MMT‘s an essential part of The Beatles’ story, and anybody with more than a passing interest in the group should give it a try. No, it’s not “A Hard Day’s Night,” which is precisely what makes it so fascinating.”

Whew, glad I got that off my chest. Meanwhile, here’s some newly released MMT outtakes from the vaults of Auntie Beeb.

Slate shouldn’t have bothered to even write such a half-assed review. The writer put no effort into the thing.

As for your post, Michael: I don’t quite understand what you’re saying about Paul here. If you admire the MMT film (flaws and all), and if it was Paul’s vision, why was that such a bad thing for the Beatles? (By the way, it’s not like AHDN and Help were perfect films without flaws.)

It’s thanks to Paul that we have Sgt. Pepper, MMT, the White Album, Let it Be and Abbey Road — their most iconic work, and the albums that still sound fresh today musically — unlike, say, With the Beatles and Please Please Me. Like it or not, new fans to the Beatles in 2012 are more likely to listen to the White Album and Abbey Road than Please Please Me or With the Beatles, and the former are still influencing music today while the latter are kinda like Elvis albums — of their time, and irrelevant today musically.

Sgt. Pepper was Paul’s vision, too. Brian Epstein seemed to have very little involvement with any substantive aspect of Sgt. Pepper. In fact, as I recall, it was Barry Miles who introduced Paul to Peter Blake and it was McCartney who brought in Peter Blake to do the Sgt. Pepper cover. I don’t recall Brian having much of a role in that at all. But I may be wrong about that. ???

I’ve always understood that Brian’s depression and drug abuse in this period before he died was because he basically had no role with the Beatles anymore and felt his connection to them slipping away. I don’t know, it just seems like you’re overstating Brian Epstein’s influence a bit and under-stating Paul’s role.

Maybe you’re right, though. Maybe if Brian had lived he would have played some role in MMT. Maybe it would have been a more controlled project. But to me, it was not just Brian alone that was critical to the balance of the Beatles. It was Brian’s relationships with John and his often-ignored and little-understood relationship with Paul that helped drive the Beatles.

For instance, in the whole Joe Orton saga (when he was writing that crazy screenplay for the Beatles), I just read recently a very interesting thing that showed just how much Paul was already running the show in the band — well before Brian died. When Brian arranged a dinner at his house to talk with Joe Orton about him writing a script for the Beatles’ next movie, the only Beatle that Brian invited to the dinner was Paul.

It’s interesting that Beatles writers have always been so eager to explore the Brian-John relationship because of the rumored sexual aspect (ooh! homoerotic scandal!) but little ink has been devoted to the Brian-Paul relationship even though by 66-67, it seems like Brian wasn’t that close to John anymore but Brian WAS working closely with Paul and they were running in the same artsy circles.

If anything, I’ve always thought it was Brian’s role in the band to relieve the competitive tensions between John and Paul. As long as Brian was alive, IMO, John felt he had an ally, protecting his interests against Paul’s dominance. That’s what was lost with Brian’s death. John felt vulnerable. … Just my 2 cents of course. 🙂

— Drew

Seeing MMT as a midnight movie makes so much sense, Michael. Because MMT appeared just as the Beatles were shedding the last of the moptop image, it was broadcast and received in exactly the wrong way, in a way that assured it would “flop.”

[And Slate as a “cyber-thunderdome for the underemployed” — thanks for making me snort through my coffee this morning! That is just perfection.]

I think the music on MMT is (with the exception of “Flying,” and with the proviso that “Blue Jay Way” could be edited down a bit), simply great. The film is certainly ragged, but ragged in interesting ways.

About Paul’s dominance: the bad news, to my mind, isn’t so much that he took charge as that John checked out. Paul kept rowing hard, while John increasingly trailed his oar in the water and then complained (generally after the fact) about the direction the boat went. Maybe that’s too harsh, but I think it’s more accurate than the Paul-as-Machiavellian schemer depiction that Philip Norman, among others, presents.

The person with the most right to complain about Paul’s dominance, IMO, was George—whose good ideas, and good songs, were too often overlooked or kept off albums in the post-Brian years. But John didn’t really assert himself to change that, either.

That the Beatles survived to produce MMT, the White Album, (even) Let it Be, and Abbey Road seems pretty miraculous, given the internal stresses they were under and the ever-growing hordes of hangers on and would-be manipulators that beset them.

Drew, I think you’re right–in general I DO overstate Brian’s influence, because my Irish-Catholic upbringing overemphasized “what might have been.”

“If you admire the MMT film (flaws and all), and if it was Paul’s vision, why was that such a bad thing for the Beatles?”

The film wasn’t a bad thing–though the reaction to it was, probably; it’s OK to follow Paul’s lead when everything works out great (like Pepper). But when Paul leads the group into its first genuine panning, Lennon especially must’ve been kicking himself.

The “bad thing” was how MMT established a new working method: Paul gets an idea, and pitches it to the other three. Lennon simply wasn’t going to be happy in such an arrangement over the long term; in the successes, he feels disenfranchised and put-upon (as during Pepper, where he sits around for months and then cranks out his allotment–that Day in the Life was a classic, probably his apogee, didn’t make him feel any more warmly towards what was Paul’s baby. And in the failures, he’s doubly resentful, first for “being sidemen to Paul” and also for not even being judged on what HE was into.

But of course Nancy is right (and glad you liked the thunderdome comment)–the only person Lennon had to blame was Lennon. Remember it was PAUL storming out of the Revolver sessions; and PAUL who got outvoted on touring; and PAUL who was last to take LSD. Only with Pepper does the group become Paul’s more than John’s; and only with MMT does this one-time thing become the new way things are done. Goldman makes this point, that there was no takeover within the group, no ouster–Paul simply filled the space John vacated after Nov. 1966, and spent the rest of both men’s lives trying to entice Lennon to really collaborate again. That Lennon wouldn’t is on him, not Paul, and the supposed artistic gap between them has always struck me as a bogus Lennon talking-point.

On to Brian and Pepper…

Nancy: I have come to the conclusion that Paul has wrongly taken the lion’s share of the blame for “poor” George being “kept off” the albums, while John got off scott free. And George bore some responsibility, too.

1. Partly the problem was George himself. On Revolver, George had the lead track and 2 other songs. They weren’t exactly keeping him off the album, were they? George could have brought more new songs in during Pepper and MMT, but he didn’t. Instead what does George do? He spends months and months trying to learn the sitar and ignoring his guitar and song writing. That was George’s choice, only to moan later about how they ignored his songs.

2. Having recently seen some passages from Don Sulpy’s book transcribing the Let it Be sessions, I was astonished to discover that John was just as likely to ignore George’s musical suggestions as Paul. Case in point: Don’t Let Me Down. According to Sulpy’s book, during the sessions for Don’t Let Me Down, John constantly defers to Paul’s musical judgment. Paul apparently not only reworked the arrangement of the song but rearranged the lyrics and added lyrics (I was surprised by that as I always thought this song about Yoko was purely a “john” song). Then John says “maybe the song needs a bit of piano?” Paul says “no” and John immediately drops the idea. Then John tells George to lay off the wah wah pedal. When George tries to suggest a different approach to the song, John rejects that. As Sulpy writes, “It’s interesting to observe that John will entertain any number of musical suggestions from Paul, but does not allow George to present his view as to how the song should be played. “

And in Peter Doggett’s book, he points out that Paul plays or sings on every George track. But John “often found somewhere else to be” when it came time to record a George song.

Sorry for the tangent here but in talking about the band’s internal dynamic — the predominance of the John-Paul axis — this seemed relevant. And I think it’s a mistake to blame Paul entirely for George feeling brushed aside when John was just as “guilty.”

— Drew

Drew, you’re absolutely right about Brian and Pepper–as more evidence see the “brown paper bags for Pepper” note. But I guess it’s my own constant project-running that emphasizes Brian’s role so much to me these days. It’s one thing for Miles to introduce Paul to Peter Blake; and then for Paul and Blake to hang out and make a connection; but it’s quite another for Blake (and Cooper, and Fraser) to actually package the LP. There’s all sorts of negotiating and background stuff that has to get done, and Paul I’m sure did none of that. The money side; the lawyer side; the contracts and timing–that’s all NEMS, and it’s all essential. For a guy who was supposedly cracking up, Brian sure cranked out the deals; not just Beatles stuff, but his other groups, and his other plans (like the Savoy), and his social life.

But however much he did for them, Brian knew that The Beatles had the final say, not him; he *worked for* J/P/G/R in a way that Klein simply didn’t. The Beatles’ creative act was music, and themselves; Epstein’s creative act was The Beatles’ career–and what they represented within British showbiz. This is why he was such a fierce, and effective, gatekeeper, letting through the good influences and keeping out or minimizing the bad.

There were plenty of unsavory characters around the Fabs before Brian died, but it’s only after he died that they got their hooks into the group. Brian was a filter, which was slowly growing wider, year by year, as the culture changed and everybody turned from kids to adults; but it would’ve never opened to include somebody like, say, Michael X, because it never opened (as far as I know) wide enough for the Krays, which Brian surely knew, and J/P/G/R probably met. If I ever write the sequel to Life After Death for Beginners, that’s where it will start.

How I think it worked was that Paul would come into contact with something, and then would clue the other three and Brian into it. Ditto Brian would do the same for Paul and the other three. Paul and Brian were running in overlapping London circles at the time, with Paul’s tending more arty and hippy (IT for example, or Miles or Fraser), and Brian’s older, richer, gayer and a bit posher. This allowed them to bring a LOT of influences to the other guys, who were all married, and living outside of London. Then there would be a period of digestion, and only after that, assignment. You see this process working positively in the development of Yellow Submarine, for example; you see it working in the negative with Up Against It; you see it not present in Apple from beginning to end; nor any of JohnandYoko’s activities, ever.

Finally, I think Brian’s depression is overstated, probably because it makes for a better story–“the end of touring broke his heart.” Most of it was probably just ups-and-downs from the uppers and downers. There’s as much or more evidence suggesting that he was rebounding in mid-’67, and I see nothing that makes me think that The Beatles wouldn’t renew his contract, for example. IIRC Goldman suggests some sort of coming storm when the Fabs find out how badly Brian screwed up Seltaeb, but that seems a stretch to me. And to be honest, if Brian had lived, I don’t think the financial pressure of “we’ll be broke in six months” would’ve ever happened, and without that, the group would’ve been free to coalesce and atomize as the four desired…even with Paul being Chief Beatle, and Yoko being in the mix.

I think Brian’s role was absolutely crucial, right up until the end, for the reasons you mention, Drew and Michael: he was a buffer between John and Paul when that was needed, and he was a filter between the Beatles and those who wanted to get their mitts on the band.

And whatever his failings, Brain did have the kind of critical project-sense that Michael talks about — something that Paul, dearly as I love a lot of his work, just doesn’t have in anything like the same degree. Much as I’m usually a Paul-defender, I have to agree with whoever said that McCartney has written some great songs and some terrible songs and can’t reliably tell the difference between them himself. He has interesting ideas, but usually follows through best with a strong collaborator.

So I think it’s fair to say that having Paul take on the leadership role wasn’t ideal — the ideal would have been for Lennon to stay in the mix more assertively, and for them to have found someone else to fill Brian’s role. But jeez, these were 20-something guys who’d led an insane life for years at this point, so it’s not really a surprise that they struggled. I don’t think it’s fair to judge any of them too harshly.

What does annoy me is the way John’s post-breakup take on what happened after Brian’s death has become the official narrative: Paul “took over” but could only lead the band “in circles.” I don’t think John ever acknowledged the degree to which 1) his disengagement contributed to the band’s post-Brian problems and 2) the Beatles’ achievements in those years were damn impressive.

In no other band do you get such a concentration of talent, which both made the Beatles great and also made them inherently unstable. Add the insanity seeping in from outside to the stresses within, and I say again it’s a miracle they lasted as long as they did and made such great music, especially post-Brian.

Paul has always been a world-class idea-generator. Brian was a fabulous packager in the old show biz idiom, and seemed to be making the leap from old show biz (think The Beatles’ Christmas shows) to new show biz (having Jimi Hendrix play the Savoy). Brian was a figure of flexibility AND continuity. These people are very rare and why Marianne Faithful spoke so touchingly of him in that bio-doc.

Artistic talents succeed because they can mimic the current vogue, or come up with something new that is popular enough to transform the current vogue. Paul is a perfect example of a traditional talent; there is little doubt that he would’ve been successful in the music business if the 60s had never happened. But to Paul’s immense credit, he does sense the benefit in iconoclasm and seeks new stuff almost compulsively. This, too, is him trying to give the audience what it wants.

John is a perfect example of an iconoclastic talent. He created his major work pretty much regardless of what was going on. Lennon’s sensibility is rooted in his own past, of rationing Britain and US/UK culture of the mid- to late-50s. Not for nothing did “Starting Over” begin like some 50s ballad–that’s who John Lennon was. But to HIS credit, he did try to appreciate traditional talent–by 1980, he was listening to Sinatra. This, too, is him trying to be an iconoclast.

So what Brian did was tune these two through his own mediating, flexible personality–blending old showbiz and new to create a third thing that, sadly, largely disappeared after the projects he developed were done.

Interestingly, the Beatles’ biggest creative successes post-Brian–White and Abbey Road–were attempts at Epstein-style mediation/blending. White tries to solve it by including everything; Abbey Road, by segregating side one and side two. And their biggest failures (Let It Be, album and movie) come when the two styles refuse to blend.

It was always John’s group. But Paul saw that John simply didn’t have enough ideas to carry the whole band anymore, even if he wanted to (which he didn’t). John doesn’t even have enough ideas for JOHN; after Yoko comes on the scene–and for the rest of his life–it’s John that goes in circles creatively, not Paul.

We know what kind of music John would’ve made, and about what. Skywriting By Word of Mouth was a less-good version of Spaniard, which was a step down from In His Own Write. John was an asteroid that slammed into the Earth in mid-1963, an event. Paul was precipitation.

It’s the John-led LPs that (much as I love ’em) feel dated. It’s the John-led period that is teenybopper music, because that’s what rock and roll was back in 1957 when John became enchanted with it. John knew this, which is why he was so touchy about being “an artist.” It is the price of iconoclasm that you become part of the tradition. And it’s the price of traditionalism that your singular innovations are never valued enough. Sounds like every John vs. Paul conversation ever.

Both John and Paul needed Brian differently, but need him they did, and there was no possibility of replacing Brian because what Brian did only worked because he’d grown into his own talent, as they’d grown into theirs.

So perhaps the way to look at MMT is that it is Paul’s one attempt at really living as John did, and John’s one attempt at living as Paul did–much more to say about this–undertaken while Brian was still alive and able to reassure both men that, whatever the outcome, he could keep the egg off their faces. And then Brian dies, and both John and Paul get scared but push on with MMT. And the resounding public failure of it cements them both into the personae that they had for the rest of their public lives.

That dichotomy eventually ended the band. MMT was–perhaps–an attempt to strike a middle ground, and if Brian had lived, might’ve worked. Every LP a Pepper.

“He has interesting ideas, but usually follows through best with a strong collaborator.”

It’s kind of a pet peeve of mine when people say that about Paul. Seems like it’s usually just a way to demean him and then elevate John as the “genius.” (Not that you’re doing that, Nancy, just that I’ve heard others make that argument: “John was a genius but Paul was only a genius collaborating with someone else.)

But sheesh, Paul wrote some of his best Beatles songs entirely or nearly entirely on his own. He produced his most influential and ground-breaking solo albums either entirely or mostly on his own — McCartney, Ram, Band on the Run, and McCartney II (whether Beatles fans like McCartney II or not, it’s highly regarded in certain hipster music circles. Yes, he also produced some dreck and yes he also works very well with collaborators but I don’t think it’s fair to say that is “usually” the case.

And in fact, it was more true of John, wasn’t it? Paul’s fingerprints — musically, arrangement-wise, production-wise — are all over John’s songs and the reverse is rarely true. So isn’t it John who needed a collaborator as much or more than Paul?

Sorry for the mini-rant. Otherwise, Nancy, I agree with you! 🙂

— Drew

John was an asteroid that slammed into the Earth in mid-1963, an event. Paul was precipitation.

Possibly one of the most profound comments ever made on this blog.

There are those who burn brightly, but briefly, and there are those who just shine on and on. John’s time was brief and brilliant, and I’ve come to wonder if his end was inevitable, a result of the choices he made inspiring someone like MDC to act on murderous fantasies. Maybe that’s being too hard on John.

I am sometimes amazed when I see Paul go on, year after year, most recently fronting Nirvana. I sometimes (often) feel like I’m 100 years old; I don’t feel particularly well, my ears ring constantly, and I winced when I saw Dave Grohl hit his cymbals at the finale of “Slack” right behind Paul’s head. Is Paul indestructible? Do his ears ring? It amazes me that he was playing loud music back when Stuart Sutcliffe was on bass, when I was a three year old. 1961 seems like a hundred years ago. And yet he goes on and on.

if Paul and John had been born in an earlier era, before “rock and roll” …would they have been successful musicians? I believe Paul would have found success as a tunesmith in any era. I don’t think John would have been a professional entertainer. He might have lived a life somewhat like his father’s, a “personality” sharing his wit and charisma on a merchant ship somewhere, maybe playing a ukulele when he wasn’t washing dishes for the crew. Possibly meeting a violent end after provoking someone.

But they were born in an era with recording equipment. They couldn’t read or write music, they couldn’t create sheet music. If they’d been born several centuries ago, and collaborated, their songs might have come down to us as folk tunes.

Perhaps their melodies would have been lifted by classical composers like Mozart and Bartok (sounding something like the orchestral versions by Ken Thorne on the HELP! soundtrack) or simply handed down, generation after generation, by street performers.

If Ringo had been born around 1889… would he have found fame as a music hall performer, or silent film star? (He got good reviews for CAVEMAN, and after AHDN they joked that he was the new Chaplin.) I remember John saying that if there had been no Beatles, Ringo might have still been a success as an all-around entertainer.

– Hologram Sam

I LOVE THIS THREAD!! So many great points made by all 3 of you guys and gal. I could read/write/talk about John and Pauls’ relationship seemingly forever. Heading to bed, but I do have something to write tomorrow. Just wanted to say thanks for all this good banter, everyone.

Drew, rant away! Actually, I think John did work best with strong collaborators too: there’s a reason he chose Spector to work with, for example. And as you point out, Paul’s prints are all over a good number of John’s best Beatles songs.

But it is true, I think, that Paul can go off the rails when he doesn’t have someone (or something) strongly pushing back. See “Give My Regards to Broad Street,” “Spies Like Us,” or “Pipes of Peace.” All the McCartney work I truly dislike falls into this category. It feels like coasting, like he’s not pushing himself hard enough.

On the other hand, the McCartney work I love responds, I think, to some kind of inner or outer pressure. “Ram” was a response to a whole lot of both. So was “Band on the Run.” And his more recent work, from “Flaming Pie” forward, shows him, greatly to his credit, being willing to push himself and allow others to push him.

Back to MMT — I agree with Michael’s points about Epstein’s role there, and it’s illuminating to think about it being an attempt of John and Paul’s to meet in the middle. Two such strong personalities and talents were always going to have strong forces pushing and pulling them, and Brian managed to keep things from getting out of kilter for a long time. I don’t think Brian’s ever gotten as much credit as he deserves for that.

I just want to say that I’m so glad I stumbled upon this interesting, intelligent blog. I’m so enjoying reading this particular thread because like CMO#9 nothing gives me more pleasure than discussing John and Paul’s facinating relationship with people who actually know what they are talking about and are also respectful. Drew your comments have been very interesting to me. And Nancy you too. I thought I was pretty well read on the group, but for once I actually don’t have anything to add to a discussion because you guys are saying it all! I hope to continue reading this thread.

In hindsight, both John and Paul realized that they worked best with eachother. I mean, it shouldn’t be too difficult to figure that out, but it seemed like they tried to convince themselves for years and years (too many years!) that they didn’t need the other to write GREAT music. I’m sure by now Paul has been quoted as such but I don’t remember reading anything where John admits that John Lennon the songwriter isn’t as good as JohnandPaul. I’d bet everything I have that he knew it in his heart though. It’s really such a shame. I get that they had to go solo and see what they could do, to prove to themselves (and the world) that they didn’t need the other to make a song or an album as great as ‘A Day in’ or Revolver. I’ve always been fascinated with the time Paul contacted John about working in New Orleans together while Paul made Venus and Mars. This is the moment that John seemed ready to do just that and join Paul but at that exact moment Yoko swept in and took John back to the Dakota where he seemingly never left. So fun to think about the possibilities (to me at least) but deep down, way back in the nether regions of my mind, I am almost glad this reunion never took place. This is the great question for me: do I wish the beatles (or just John and Paul) had created more music together or should I be content with what they did in the 60’s? I always answer the latter. It would be impossible to even come close to the high level they produced in the 60’s and anything made after that point would inevitabley have been a let-down.

Bit of a ramble here, sorry bout that but I felt like I had to contribute something.

-Craig

All who’ve commented: so glad to know this is giving you some enlightenment/pleasure. Thanks for adding your thoughts, and please return!

Craig: honestly, I wish John and Paul could have fully made their peace. As to wishing they’d collaborated musically after the break up — that I could pass on. It would certainly have been interesting, but God knows they’d already given us plenty. However, I don’t think either of them ever fully got over the damage they did to each other from 1968-72, and that’s a real shame. I think if John had lived they would have found some way to broker a more lasting detente, and that would have been good for the souls of them both.

I suspect that any collaboration they’d engaged in post-breakup would have looked quite different than pre-breakup, because the Beatles could no longer be the emotional lodestone of either. Once John and Paul found emotional focus outside the group, things were never going to be the same. That’s not to say things needed to be so nasty, but to say that that time had truly passed.

Great point Nancy. This (finding emotional focus outside group) is why great, classic, iconic music will always be made by people in their 20’s. I’ve voiced this to friends/family before and not everyone is receptive to this viewpoint, for various reasons. But it’s not a crack on geezers or a version of ageism. Once someone finds something (usually a woman/man) that becomes more important than the group/music….it’s all downhill. 🙁 Good for them in that hopefully they’ve found a loving relationship…bad for us in that we get Some Time in New York City/Give My Regards to Broadstreet.

-Craig

Very true that once they found emotional focus outside the group things would never be the same. I think that’s key in fact. When they were together the group was their soul emotional focus. They were ‘married’ to each other and to the group, and they were more entwined with each other than they ever were, with the women in their lives. That ended in 1968 and I don’t think they would ever have been able to return to that level of intensity again.

So while I do think they would have returned to each other eventually, I don’t think they could have duplicated what they did together in the 60’s. It may be a cliche, but it’s true that you can never go back. At least not completely.

I just wanted to add although it may be slightly OT at this point in the discussion, that I agree with you Drew, about the Sulpy book. I think it should be required reading for Beatles fans because it is so enlightening. Few books give you a fly on the wall (unlike that useless bonus cd in the LIB Naked package)view of the real dynamics during the last days of the group. The Sulpy book really opens your eyes. I agree that it seemed to be John, and not Paul, who was unaccepting of George. In fact John gave George a royal hard time, yet he seemed to agree with everything Paul said. So what had changed really, from the early days?? And yes I was also surprised by the amount of work Paul put into Don’t Let Me Down. In fact I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that, that song was as much of a true collaboration as the early L&M songs.

I’ll always be grateful for the Fly on the Wall bonus disc because it introduced me to…Takin a trip on an ocean liner, I gotta get to Carolina! Love that ditty – my favorite Ringo singing performance (no joke) and Paul helps Richie out by playing a quick and jaunty yet pretty piano tune.

Fantastic discussion here. A couple thoughts:

First, I don’t think it’s quite accurate or fair to imply that the John-led Beatles albums are more dated because of John’s leadership rather than because of the era in which they were made. The Beatles could never have survived to make “Sgt. Pepper” had they not already made “A Hard Day’s Night,” and, frankly, I think nowadays, you’re as likely to find aspirant indie-rockers singing the praises of the Beatles’ early work as they are “Abbey Road.” These types of things go in phases, and at the moment, the quasi-symphonic, vaguely proggy sensibilities of “Abbey Road” (just to stick with that record) are less in sync with the immediate, minimalist aesthetic that a lot of younger groups prize. Furthermore, White, Pepper’s, AR, and MMT wouldn’t be considered nearly as relevant works of rock without Lennon’s contributions (or Lennon-led collaborations). Without tracks like “Happiness is a Warm Gun” or “Come Together,” those albums would sound a lot more like McCartney solo records that, while great, wouldn’t be as emotionally or psychically encyclopaedic as they are.

Second, I think a HUGE amount of the bitterness from John to Paul post-1972 was due to resentment that, in fact, he did seem to need Paul to do great work. Whether he fully admitted this to himself or not I don’t know; knowing Lennon, it seems quite possible that he had a lingering feeling that he never fully articulated to himself. Just witness the story of him hearing “Coming Up” and then declaring, “Well, I’d better get to work.”

-Michael

Interesting points about the Sulpy book, girl and Craig. I haven’t managed to make myself read it (that much detail about the “Let It Be” sessions — not sure I can take it!) but maybe I will nerve myself and give it another try.

I think it’s fascinating, and very telling, the way John in particular told the story of “Let It Be” after the fact. It’s as if it took an emotional shape for him that became more real than the recordable day-to-day events. Perhaps he needed to be so angry at Paul in particular, and so convinced he could never work with Paul again, in order to leave the group.

The emotional focus outside the group thing — Craig, that does often seem true about why great rock/pop music has disproportionately been made by young people. Although I wonder if that’s changing, or if our recognition of what’s great is widening a bit. That could be a whole other thread . . . .

One last thought about John and Paul post-breakup: I think if they had collaborated musically, it would if nothing else have tended to take some pressure off them internally and externally. They could have made some kind of peace, I think, and having collaborated, they would perhaps have no longer been hounded to do so. As long as they didn’t do it, and as long as it remained for John an emotional “I never will” thing, the idea of their working together had a lot of power over them. If they’d just done it, I think a lot of that power would have drained away.

A damn shame that John didn’t go to the “Venus and Mars” sessions in New Orleans when John invited him. That might have worked. I can’t at all be sorry that John got back together with Yoko at that point, since that seemed to make him happy, or that they had Sean — just wish that the whole John and Paul conflict could have been more definitely laid to rest beforehand.

Great comment, Michael. Right on the money. “quasi-symphonic, vaguely proggy sensibilities” <--awesome, so accurate I guess I skew towards “blaming” John for the dated sound of the John-led records (which I love–Hard Day’s Night vies with Pepper to be my 2nd favorite Beatles LP, and Goldman called HDN practically a Lennon solo album, FWIW) because John himself said that he didn’t know where to go/what to do after touring; how he grew increasingly distant from the Beatles thing after it launched from its R&B roots; how his reaction to post- Pepper McCartney was either musique concrete or self-conscious “no jiggery-pokery” (ie, pre-64) styles; and how he continually returned to the tropes of 50s era rock throughout his career. He did “Rock and Roll” in his 30s, and while that’s a perfectly fine record for a fan, for John Lennon it’s incredibly flaccid and uninteresting. There is not one single track on it not thoroughly blown away by the original, and that’s because John recorded it as a FAN, not as a creator. The point is muted by the things you say, but I feel one can make a good case that Lennon’s sensibility was rooted in 50s rock and roll, and that he–unlike the rest of the world–preferred that to The Beatles, and everything that came post-Beatles. The peculiar tragedy of being a Lennon-like innovator is that you’re still stuck liking whatever it was you replaced–not least because your relationship to your innovation is much more complicated than everybody else’s is. In 1957, John was a rock and roll fan; in ’67 he was a creator, and while there are great pleasures to that, it’s that ecstatic fan-feeling that popular artists want so badly they turn themselves into creators. But the creator-feeling is never as pure. One chases it. Nancy, I think John and Paul not getting together in 1975 was a real shame, not only for the music, but because I think it–totally unnecessarily–kicked off five more years of isolation and depression for John. The best thing for both of those guys would’ve been to cut out all the famous-person bullcrap and just do what they loved, which was writing songs together. Lennon hated needing Paul, for lots of obvious reasons; and Yoko was all too willing to stoke that hatred and encourage him to need her instead. Of course the best thing would’ve been for John to work on the root causes of all this stuff, but he didn’t because of all the famous person showbiz bullcrap.

Michael-

Point well taken, and I understand what you meant better. I think you’re right that that’s the peculiar dilemma of the innovator (of the type Lennon was). Even as he recognized that “A Day In The Life” and “I Am The Walrus” were good songs, John didn’t quite seem to understand that they were much more than that—that he had quite simply demolished the boundaries of pop music, fusing his instinctive surrealism, his love of Lewis Carroll and whatever other writers he happened to pick up from living at Aunt Mimi’s, with the subversive roots of rock’n’roll to create something much more sophisticated than “Tutti Frutti” that was, in its own way, no less unsettling. I go on at length describing that because, I think, in the end, John listened to those songs and thought, “they’re good records—but they’re not ‘Heartbreak Hotel’.” So instinctive was his talent that he didn’t realize stuff he knocked off to fill his quota on “Paul albums” opened up a whole host of new opportunities.

People like Paul McCartney, Brian Wilson, and Pete Townshend seemed to understand the awesome power of what they were doing, whereas Lennon, despite being enormously more intelligent, sensitive, and full of potential than Keith Richards, was basically, like Richards, a rocker who was essentially motivated by a teenage desire to recreate the joy of listening to his heroes, as you point out. In Richards’ case, heroin allowed him to pretty much ignore that he was squandering the ability to, say, turn “Sympathy for the Devil” from what could’ve been a pedestrian dirge into a terrifying, dangerous, glorious samba. In Lennon’s case, Yoko Ono more or less served to confirm every creative impulse he had as creatively valid and utterly brilliant; despite the many ways in which she “challenged” him, she never did—or could—the way McCartney did.

-Michael

I agree completely Michael, referring to their early lps. I personally think they are just as musically relevant as the later ones, but of course in a differnt way. If they weren’t just as relevant in their own way MacDonald wouldn’t have spent so much time writing about them, and neither would Everett or Riley. They would have skimmed over them as if they were dated period pieces…but they didn’t. And yes it’s true each album was important to the album that succeeded it. So without AHDN or With the Beatles, we wouldn’t have had Rubber Soul or Pepper. To me it always seemed like a musical domino effect.

Hey – I’m the one who brought up the infamous failed 1975 J/P reunion! Mike, I was particularly interested to hear your take on this period. (Although, have we discussed this before?) What did Yoko do to John to make him drop everything (friends, music, LIFE) and return to seclusion in the Dakota under the guise of a bread-baking househusband? Was he brainwashed? Or did he simply give in to his legendary laziness and accept Yoko’s offer of laying in bed all day while she took care of business.

Nancy – I don’t buy the John-is-happy theme that J/Y so desperately tried to sell us on for his 75-80 Dakota period. I simply don’t believe it and never will. I know he could be lazy but John enjoyed living life too much to be content couped up on the Upper West Side for five straight years. I’m convinced he was hooked on something, most likely heroin during that time.

Anon Michael – you make great points regarding John’s input on AR and White. But I think the point was that those albums wouldn’t have even been made without Paul taking charge and leading the group. Like it or not (and clearly John did not) someone has gotta lead a group and point it in direction. In some ways, Paul can’t win here. He takes charge because no one else would and they produce some of their best work. If he hadn’t taken charge and simply felll into step with John (ie making a movie and laying by the pool out in the suburbs), I believe the beatles discography would be much shorter and less well regarded. The beatles as we know them would be completely different. Paul should be endlessly commended for taking charge and wringing the most out of the other guys as was humanly possible. He definitely should not be viewed as some bossman who cracked the whip and was unreceptive to his band members hurt feelings. Sometimes that’s the way I thinkl many writers/fans feel about him.

-Craig

Girl, a “domino effect” is exactly right, IMHO. This evening in the car, my wife played a bunch of her Beatle faves on “shuffle” and the lack of chronology was actually weird for me–that’s how much one song leads to another, one LP leads to another.

Michael,

Of course Yoko could never challenge John in that precise way, because she encountered him as a full-grown man–a finished product. John and Paul (and George and Ringo) grew up together, in the same time and place, and grew into complimentary pieces of a whole that had been aborning since John was 16. It wasn’t just ineffable magic that made The Beatles great; it was that they had all grown into what each other needed most, creatively. And one can see how that pinched, and why Lennon especially would hunger for new opportunities. But that doesn’t change the facts of the matter–the stuff with Paul is, with maybe one or two exceptions, the stuff that will last. IMHO.

>>I think, in the end, John listened to those songs and thought, “they’re good records—but they’re not ‘Heartbreak Hotel’.” So instinctive was his talent that he didn’t realize stuff he knocked off to fill his quota on “Paul albums” opened up a whole host of new opportunities.

John was instinctive, yeah, in that he had great taste, and a great voice, and a natural feel for it all–but also remember that instinctive was the pose he was comfortable with. He talked of having a “formula” in the mid-60s that he used–and then either forgot or never spoke of–to write hit songs. I think there was plenty of premeditated craft in Lennon’s work, and the “improv/instinct” stance was as much self-protective as factual. As with comedy, fans give pop music much more leeway if it seems off-the-cuff or unstudied or natural. But it’s never natural; it’s never effortless; even the stuff that just comes down from Heaven is the residue of a gazillion hours of work and study.

Michael, would you be willing to expound on these ideas of yours in a post? I’d be interested to hear more.

CMO, I haven’t a clue why John moved back into the Dakota in 1975, but Goldman did, and he’s the guy who interviewed all those sources. Sudden changes in an historical narrative always suggest to me that we don’t know the full story.

As in any relationship, things happened within John and Yoko’s relationship that only John and Yoko know/knew about. But their dramas and decisions all had millions of dollars at stake, and the gossip sheets lurking in the background–especially in the 60s and 70s. So I would not be surprised if their relationship had some funhouse mirror distortions, but I try not to judge, and simply feel compassion for all concerned. Whether they acted kindly or badly in one instance or another, the relationship must’ve been very confusing and difficult. I don’t think there were any bad guys in the story; but I also get the sense that there were some brutal moves and accomodations, too.

Nancy I know what you mean regarding the Sulpy book. It isn’t exactly entertaining reading. In fact I had to force myself to finish it bc I’m a Beatle knowledge junkie. It was very plodding but in the end I’m glad I read it bc as I’ve said it really changed forever how I view the band and the breakup, and the roles each of them played. A more entertaining book on the breakup would be You Never Give Me Your Money by Peter Doggett. Fantastic book! That one is my favorite.

“Paul should be endlessly commended for taking charge and wringing the most out of the other guys as was humanly possible. He definitely should not be viewed as some bossman who cracked the whip and was unreceptive to his band members hurt feelings. Sometimes that’s the way I thinkl many writers/fans feel about him”.

I agree completely Craig. It’s frustrating to read over and over again, Paul written about in that simplistic way. So many Beatle bios are really badly researched and should be avoided.

This evening in the car, my wife played a bunch of her Beatle faves on “shuffle” and the lack of chronology was actually weird for me

This may sound strange but lately I’ve been listening to my massive Beatles playlist on ‘shuffle’ and yes it does sound weird but for some reason I like the weirdness of it, if that makes sense. At the very least it’s a jolting experience to hear All My Loving and then Helter Skelter!

Craig, I think you were the one who brought up that failed 1975 reunion some time ago, so thanks for that! It does seem like the great opportunity that never happened — far enough after the breakup to have been emotionally possible, and coming at at time when John was somewhat open to it.

I don’t buy the whole “baking bread in complete happiness” narrative of the Dakota years either, Craig, but it seems clear that John found something with Yoko that he needed and couldn’t find elsewhere. Sexual connection with someone he also felt connected to emotionally, for one thing — always before he’d had one or the other. And with Sean he got to be the father he wasn’t with Julian.

And Michael, I think your point about John’s resenting that he needed Paul to be at his peak creatively is absolutely correct. Post-breakup, it galled them both that they needed each other, but it seems to have galled John more than Paul.

Michael G., I’d forgotten that Gerber called AHDN virtually a Lennon solo album. That’s a real overstatement — what about “And I Love Her,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” and “Things We Said Today”? — but I can see what he means. It’s the last album that Lennon dominated.

And while I also see what people mean about Lennon’s being rooted in rock tradition, in interviews I think he DOES recognize the artistic greatness of songs like “I Am The Walrus.” Maybe it was just Lennon’s sensibility to always be torn between two things (rootsy rock and experimentation, self-definition and safety, etc.) that led him to talk up the early stuff. Maybe it was resentment of the strong roles McCartney and Martin played in the later work.

That’s one other thing that strikes me, besides Lennon’s resentment of McCartney, post-breakup: his criticism of George Martin. John once said he wished he could rerecord all the work, even “I Am the Walrus” and “Strawberry Fields,” because none of it sounded good enough. A real slap in the face to Martin, who’d labored so hard to bring John’s visions to concrete fulfillment.

In post-breakup Lennon I always hear someone trying to convince himself he misses nothing, because there was really nothing worth missing, and not quite convincing himself.

“I think your point about John’s resenting that he needed Paul to be at his peak creatively is absolutely correct. Post-breakup, it galled them both that they needed each other, but it seems to have galled John more than Paul.”

Agreed. In fact, I’m not sure Paul did need John all that much post-breakup in the 1970s. Paul did exactly what he wanted to do in that period and he did it with great success: He released the kind of albums he wanted to release (McCartney, Ram) and then formed a new band (Wings) with an entirely different sound from the Beatles that released 5 No. 1 albums in a row and successfully toured the world.

Meanwhile, the only one of John’s solo albums that reached No. 1 was Imagine. And ticket sales for John’s few solo shows in the early 70s were slow. I think people forget how much John was struggling career-wise in the 70s. And Paul didn’t start to suffer artistically until the 1980s when the one person who had motivated him throughout the 70s was gone.

After John’s murder, many critics in the 80s and 90s loved to say that Paul needed John — artistically. And as I said, that was true in the 80s and 90s when Paul did struggle artistically (I think it took Paul a LONG time to recover from John’s death, and he really didn’t start producing strong work again until the mid to late 90s. But it’s also true that Paul DIDN’T need John to produce great work. Witness: Today’s younger critics have embraced Paul’s solo work (in both Ram and McCartney II) today as brilliant or ground breaking.

As for John’s resentment of George Martin, I have always thought that John was just jealous of Paul’s close relationship with George Martin — just as Paul was jealous of John’s close relationship with Brian Epstein. And maybe Paul’s close relationship with George Martin was more of a threat to John because it involved the music — whereas John and Brian never collaborated on the band’s music.

— Drew

Good points Drew. I think the important thing to remember about John versus Paul in the 70s was the different pressures on each man. This was really shaped from 1969-71 by Lennon’s media blitz, but you can see it much earlier.

Paul was seen as basically another rock star–even though I’d argue that as an artist, he was easily as inquisitive and as wide-ranging as Lennon. But the important thing is that McCartney accepted this definition of himself. He did what he thought rock stars do–toured, gave interviews but stayed a bit aloof, didn’t resent teenyboppers, measured it all in ticket and LP sales. Only occasionally did his artistic curiosity leak out and push him into less-popular places.

John was seen as basically a political/cultural figure, a prophet of this new age, whatever it was. The only person who carried comparable weight was Bob Dylan, but he doesn’t seem to have the level of drug issues or emotional damage that Lennon did. So it was harder for John, and sapped the energy he had earlier put into music. That’s why the guy couldn’t write songs like Paul–he was carrying the world on his shoulders. Everything he did had to MEAN something. Even though he gave it to himself, John Lennon came to resent that pressure, and who wouldn’t?

Lennon mostly accepted this definition and did what he thought a prophet would do. This constantly threw him into conflict; and while that’s manageable when you’re Yoko Ono, the scale of attention (both positive and negative) upon John Lennon was infinitely more.

Unlike McCartney, who was surrounded by models of how to solve problems, Lennon’s life strategy was simply unworkable over the long term. It asks for too much. Not every LP is going to be Plastic Ono Band or Imagine–yet even if it were, for someone who’d had the top four singles on Billboard as a 24-year-old, not having commercial success must have been bitter. Add to this watching your ex-partner having more of it, and it would’ve been excruciating.

Looking at the two guys this way–seeing the 70s J&P as the only semi-willing playing out of what Lennon compulsively pumped out into the media from 1968-71–explains a lot. It explains Paul’s desire to reconnect, and John’s perception of that as a personal defeat; it explains both men’s conflicted relationship to what they did have (prophet-like reverence on the one hand, mainstream popularity on the other), and hunger for what the other seemed to get effortlessly; it explains their bitterness and resentment towards each other, as they personalize the bind each is in.

I know this all may feel like overthinking it–but that’s the degree to which the false dichotomy set up by John has dominated the discourse ever since. Paul is an incredible artist, in whatever way wants to define that; to dismiss him as “a showman” or “a tunesmith” is to ignore/deny a ton of his work. Similarly, to ignore/deny John’s desire for, and occasional ability to achieve, vast popular success, is fall for a trick, an image as flimsy as a publicity photo with the ciggie airbrushed out. [Continued next comment]

[comment continued]

Both guys wanted both, because both guys had already achieved both with The Beatles. As solo artists, but their hit rate labored under an unfair, inaccurate, and ultimately destructive story that John Lennon told to get himself out of the partnership. He had to make The Beatles seem wanting–to us, and most importantly, to himself–in order to leave it. (Whether or not he HAD to leave it, and why he was so convinced that he did, is another comment.)

As time passed, and The Beatles became history the need for the black/white story was lessening; and that’s what makes me think that John and Paul would’ve worked together again, and been more commercially successful than they were as solo acts; and been more artistically relevant, too.

The wild card is, of course, Yoko Ono. Part of the whole Yoko package is a bright line between art and commerce. Art is stuff that the squares don’t get–that’s how you tell it’s art–and its primary goal is to define and gratify a small cognoscenti. Popular stuff, on the other hand, can ONLY be commercial, and so popular success automatically invalidates a piece of creative work. Makes it false, impersonal, disposable, unimportant.

This is a 50s idea, not a 60s one. Far from avant-garde, it’s old-fashioned, and totally in retreat by 1965 or so. It’s why Yoko didn’t get along with Andy Warhol, for example, and (to my mind) is totally, irrefutably exploded by The Beatles in particular.

Which is why it was so attractive to John Lennon, living in the world that Paul’s artsy Pepper had created.

Which is why he spent the rest of his life trying to be a quasi-religious figure, not a rockstar.

But John wasn’t a guru–there’s nothing BEHIND his beliefs, which shift constantly–he was a musician. Eventually he would’ve come back home to that. Just as Paul’s working with John would’ve made McCartney increasingly emboldened to reveal himself in his music. We know they would’ve done this because they’d done it before, in the 60s.

Michael-

I’d love to expound on the issue of Lennon’s creativity and rock’n’roll in a longer post, thank you for asking! I’m very busy until about the fifth or sixth of January, but after that, I’d be happy to. Where should I send a draft?

-Michael

Michael, send the draft to contactmikegerber@gmail.com. That will forward to me.

Looking forward to it!

It strikes me that the comments about the Lennon-Epstein vs McCartney-Martin emotional pairing actually have played a relevant part in the breakup of the group. It’s been clear from the beginning that Epstein loved all the boys but was in one way or another IN love with John. McCartney, like the overachieving younger son, always seeking parental approval, gravitated more towards Martin (the more motherly-creative parental figure). In this light, George and Ringo were like the even younger siblings, forever overshadowed by the older, more sophisticated brothers from whose shadows they both knew instinctively they would never escape.

When Epstein died, the first film of the Beatles’ reaction, shows John firmly in the older brother/family spokesman persona attempting to balance his shock, grief and confusion with his duty to the family (group). Yet, like sometimes happens, after Epstein’s death, Lennon – the devoted, though often in conflict with Daddy, oldest son – collapsed emotionally. While he had sometimes chaffed under Epstein’s management, he was secure in his place and able to parlay his ‘rebelliousness’ (he was such a rebel he loosened his tie on TV shows to show how radical he was!) into a viable persona for success. Without the special attention he had always enjoyed from Epstein, Lennon was rudderless.

In this circumstance, Paul, the second overachieving son, naturally rises to take command. The older brother is emotionally incapable of taking charge, so number two steps in. Paul, as second brother, didn’t seek to supplant John’s role, but to keep the family moving. By the time John came to fully realize how he had failed to fulfill his role it was too late. Any attempt to step back in would break against the rocks of Paul’s newly established public role as the group motivator.

Couple this with John’s relationship with Yoko, a strong woman, who, I am convinced, totally loved him from day one, and suffered the insecurity of knowing the mercurial nature of John’s personality, fearing he could drop her as quickly as a broken guitar pick. Psychologically, Yoko gave John a feeling of empowerment in that he was now ‘a man’ with a mate/spouse and therefore should have been, in his mind, more understood in the group as the one to listen to. However, the still unresolved issues he had with his relationship with Epstein continued to prevent him from being able to fulfill that role, and now coupled with Paul’s success in taking over the leadership role in John’s emotional absence, grated on him.

It was a recipe for disaster from a familial/group dynamic, and like in too many families, led to exactly the kind of result we see historically. John denigrated the success, quality and value of the Beatles era, railed against Paul and George Martin, and belittled George. Paul, continued to overachieve and never felt at peace with the success he found. George generally sided with John against Paul despite John’s mistreatment of him and then avoided even mentioning John by name in his autobiography. Ringo, the baby of the family, lived on recognizing the shortcomings of his older siblings, forgiving and refusing the comment on them, while being treated publicly and personally as the less than stellar but beloved baby brother of the other three.

Yep, group and individual therapy might have done them all a world of good.

Anon, since you brought up family dynamics, I will say that I’ve always found the alcoholic family matrix strikingly appropriate for The Beatles…Even put it in the novel.

http://kathyradina.com/role-play-family/

[…] Is Love,” casting the group as ambassadors to the world, a role they still occupy today; and Magical Mystery Tour, the world’s first midnight movie. Given what The Beatles did from August 1966 to August 1967—a vast maturing and self-redefinition […]

Sir Macca himself would agree with you, Michael! Though I don’t think that really comes as a surprise. I was listening to an interview he did with Roger Scott in 1984 and his word choice was so similar to this post that that I felt it necessary to come back and write this comment. When talking about the ill-fated Give My Regards to Broad Street, he refers to Magical Mystery Tour as a midnight special kind of thing, said it was shown to the wrong audience, and that it was similar to a home movie. Here’s the interview: https://youtu.be/pbPXoRmrmiY. And here’s the quote, poorly transcribed by me:

“What happened was it was shown I think on Christmas Day or Boxing Day…I think it was Boxing Day. When traditionally, it’s like Bruce Forsyth, Morecambe and Wise — the fun, family shows. This was really more of a kind of MTV, midnight special, tube offering, really, Magical Mystery Tour. It was for…the heads, the folks, you know, the kind of ‘hey man,’ and the…60s crowd. Um, we got on a bus and made a film, it was crazy. But if you look at it now, um, as I, well I haven’t studied it but I’ve seen it occasionally. You know, it’s here and there. Now it looks more like a cult film. It looks like very much a 60s thing. And I know a lot of young directors actually look at it and say, you know, there was something there. So on that kind of level, I do think it was successful. It’s the kind of thing that, in its time, it was ahead of its time. It was very poorly produced for peak-hour television. It was almost like a home movie.”

I think he’s right; it was just a bit ahead of its time.

With the Beatles in it, MMT is one million times more watchable than any movie Andy Warhol ever made.