- Memories of Nicholas Schaffner and The Beatles Forever - January 4, 2026

- Old Draft: Beatles Folk Memory 1970-1995 - December 8, 2025

- Lights are back on. - December 8, 2025

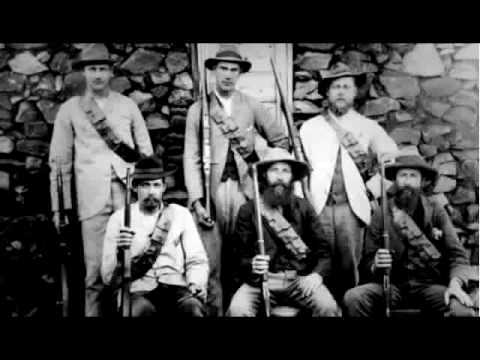

TOO COOL CATS: George Martin and Brian Epstein, undated.

(Before we begin: Any readers not familiar with the details of Beatles manager Brian Epstein’s life might wish to watch this 1998 BBC documentary, “The Brian Epstein Story.” It’s the best potted history of the man.)

MIKE GERBER • Commenter Annie said this in a recent comment:

Question: George Martin is quite adamant in his ’78 book that the Beatles were definitely going to cut Brian loose. What do we think about that?

I haven’t read All You Need Is Ears, and it’s not at the library down the street, so somebody please send me the extract and I’ll post it here. On thinking about the issue, however, I found that an answer came to me immediately, which I wanted to write down and present for dissection.

But first, what everybody else thinks regarding the question at hand: If Brian Epstein lived, would he have remained manager of John, Paul, George and Ringo?

Goldman, Norman, Gould and Spitz

The original agreement between Brian Epstein and The Beatles called for him to receive 25% of their income in exchange for management; this deal was due to expire on October 8th, 1967. This much was customary—but there was a wrinkle: according to Goldman, when renegotiating the group’s contract with EMI in 1966, Epstein had signed himself on to receive 25% of that income in perpetuity whether he managed them or not. “None of the Beatles had troubled to read the agreement,” Goldman writes. “When [they] learned later what Brian had done, they were deeply shocked.” In Goldman’s world, Epstein had screwed The Beatles, and when they discovered that he had, Brian was toast. It was only his death (suicide?) that had spared him this final, tawdry rift.

In one of their few points of agreement, Philip Norman’s Shout! shares this ominous note. Norman quotes Larry Parnes: “[Brian] told me the Beatles were leaving him. He was losing Cilla [Black] and…the Beatles were giving him notice.”

But here’s what caught my eye: Goldman and Norman differ as to why. Goldman suggests that it was John who was dissatisfied (claiming to Allen Klein that Brian would’ve certainly been chucked), while Paul was actually growing ever-closer to Brian. Norman paints the exactly opposite picture, saying that Paul was “unimpressed” by Brian’s renegotiation with EMI. “Paul,” says Norman, “was the instigator of a feeling within the Beatles that they had now outgrown their need for a manager.”

To balance this, I went to Jonathan Gould’s Can’t Buy Me Love, and found another tidbit worth copying out: “Friends who visited him in the sanitarium [where he was taking his “sleep cure” in May 1967] were amazed to hear him express doubts about his future as the group’s manager.” So Brian himself thought he was going to get the boot? Not so fast—here’s more from Gould:

“Epstein and Paul McCartney began to discuss the formation of a Beatles-owned investment company that would consolidate the group’s holdings and provide them with a more comprehensive solution to their tax liabilities. The idea of Apple Corps (as the company would be called) was entirely consistent with Epstein’s plan to separate his interest in the Beatles from his interest in NEMS when his contract with the group expired in October 1967…No one with any knowledge of the situation regarded Brian’s occasional doubts about his future as the Beatles’ manager to be anything but paranoia. By the time of his Melody Maker interview in August of 1967, he felt confident enough to state publicly, ‘I am certain that they would not agree to be managed by anyone else.” [underlining from MG]

DOING DEALS: Nat Weiss and Brian Epstein and paperwork.

With the benefit of all these books preceding him, Bob Spitz at first seems to come down in the “Brian would’ve been fired” camp, saying that by early 1967, he was merely “a figurehead.” Spitz quotes Peter Brown saying, “Robert [Stigwood] seemed like the solution to our worries. Even though no one came out and said it, Brian was no longer paying attention and couldn’t adequately run the company as it was.” But then the story gets murkier and, to his credit, Spitz follows. “Brian wanted to get rid of Stigwood,” Nat Weiss said. “[By May ’67] he’d already begun proceedings…to undo all that.”

The Beatles seemed to have no idea about Brian’s machinations with NEMS and would’ve certainly bridled at any connection with Stigwood. But Nat Weiss also said, “At worst, they might have renegotiated his commission, reducing it from 25% to perhaps 15%, and I told Brian this whenever he wrestled with the subject.” According to Spitz, “deep down, even Brian believed they would ultimately keep him on [saying] ‘It’s a matter of chemistry.'”

Still the “Fifth Beatle”

With many other remedies available—like a reduction in commission, or a change in job-title—it seems to me very unlikely that The Beatles would’ve fired Brian Epstein. It might’ve seemed so to George Martin, but that was because he only saw The Beatles in one capacity, as recording artists; Brian saw them as a phenomenon, an entity—what today would be called “a brand.” That was his gift.

Though Norman and Goldman point to dissatisfaction in with Brian’s performance, the fact that they assign it to their respective bete noires, Paul (Norman) and John (Goldman), and say that the other one was getting along splendidly with the Beatles’ manager, means that more than a little ax-grinding can be heard. It seems that at the time of his death, Brian was as much “the Fifth Beatle” as ever. If Paul wanted to create Apple (and he definitely did) and The Beatles needed it (and they definitely did) Brian was the obvious person to implement that, and run it afterwards. And if John and Brian’s emotional bond was 1/10th as strong as has been suggested, it seems unlikely that John would’ve sacked Brian under any circumstances. Remember that it was John who was gripped with fear on the news of Brian’s death.

ODD MAN OUT: Brian Epstein at the Shea Stadium concert, August 1965.

Even if the group never toured again—an unlikely thing, since “never” is a awfully long time—Brian Epstein looked to be very useful to Paul, and very necessary to John. The Beatles were not firing Brian Epstein. His role—and his percentage—would’ve been adjusted. He would’ve run Apple, and we know this because when they needed someone to run it, they turned to Neil Aspinall. The Beatles were famously insular and had Brian been alive, he would’ve been the obvious choice, not only because The Beatles didn’t need him to do the things he used to do, Brian didn’t want to do that job anymore. This is why he involved himself with another manager in late ’66 and early ’67—not to sell Stigwood The Beatles in some underhanded piece of self-defeating stupidity, but because he had a bunch of clients and wanted to transition to another business.

Brian’s emotional role was as strong as ever—witness John’s flowers to him at the Priory (“I really love you”), and now this letter from Paul we’ve been talking about. Brian’s not having a clear business role was a temporary thing, which lasted from August 1966 to January 1968, when Apple Corps was formed. Had Epstein not died, Apple would’ve started even sooner.

Would there have been a “tension album”?

Brian certainly would’ve eased a lot of the tensions within the group; in fact, he had already identified this as his main role, working with Paul on the pre-planning of “Magical Mystery Tour” to ensure each Beatle got their fair share of screen time. He, too, was a battle-tested foxhole buddy; an arbiter they all knew and trusted; a gentle counterweight to Paul’s bossiness and John’s impulsivity. And his mere presence was a definite break on egomania—he’d known them when, and vice-versa.

It seems likely that Paul’s anxiety over the band would’ve been lessened, allowing him to ease off when the others clearly weren’t feeling it. (Pepper was a Paul show, but John was doing excellent work during this period, too—it’s only after the fact that he claimed to be miserable.) It’s impossible to say whether John would’ve still cleaved to Yoko as he did post-India; I suspect that relationship would have come about in a more measured, less desperate way, had Brian been alive to provide his portion of emotional support to John. And we shouldn’t discount the psychological injury of John’s losing yet another parental figure to sudden death—if Brian Epstein lived, would we even know the name Yoko Ono? Possibly, but possibly not.

What effect would this have had on the music?

GROOVY: Sixties fashion claims another victim, 1967.

This is an even more interesting question, because Brian’s ownership of the Savoy Theater in the West End suggests a solution to the problem of touring. Between 1967-69, the concept of rock bands, touring and concerts all underwent vast changes, and while it makes perfect sense that The Beatles had no interest in the kind of touring and performing that ended at Candlestick Park, they very well could’ve enjoyed staging happenings (their own version of “The 14-Hour Technicolor Dream“), creating performance films like “Rock and Roll Circus,” and surprise appearances. In fact, they were moving in this direction before Brian died, by contributing “Carnival of Light” and creating “Magical Mystery Tour.” I think it’s not only possible, but likely, that Brian Epstein’s Savoy would’ve become a London version of the Fillmore, with his most famous clients as frequent guests and occasional performers. Think about how much less tension there would’ve been inside the group if George could’ve gigged with The Band or Clapton or Delaney and Bonnie without having to “go outside the family”? Ditto with John and Yoko—think of how naturally the Savoy could’ve become Yoko’s homebase in London, the place where she staged happenings, screened movies, and generally held court. And think of how much that would’ve helped minimize the bad vibes of 1968-70. Plus no Allen Klein, no Eastmans representing Paul, and no lawsuit to dissolve the partnership. (And Brian might’ve even shown up in India, to his possible personal benefit.)

Brian Epstein’s death turned back the clock to 1962—before they’d all grown up—a lethal reversion of dynamics within The Beatles and their circle which led to the demise of the group. As their trusted business intermediary, and someone who was skilled at making it possible for each Beatle to pursue his interests within the pre-existing arrangement, Brian Epstein was essential—probably much more than he knew, or The Beatles’ themselves realized.

Downers breed downers

NOW I’M ONLY 32: Brian Epstein on the roof of his home on Chapel Street in London, the week of his death.

I go on regularly about the role of luck in The Beatles’ story, how much wonderful luck they had before August 1967, and how much rotten luck they had starting then. This is never clearer than when discussing their manager, and if his death was accidental—which I believe it was—it was simply a stroke of terrible luck that caused them to revert to the much more contentious, much less stable arrangement they’d had pre-Epstein, but with unimaginable money, fame and power added to the mix. A breakup was not somehow inevitable, as the four of them “grew up”—such claims are attempts to stave off sorrow and excuse bad behavior. They’d fought from 1957-62, but had the shared goal keeping them together; the John-Paul tension over Yoko had been presaged by John-Paul tension over Stu. Brian changed the dynamic, made them all act more like grownups and less like the teenaged friends they’d all started as. Post-Brian, the old fissures reemerged, and since the mountaintop had been reached, there was a natural instinct to say, “What do I need those guys for?” The Beatles of 1968-73 are less mature than the moptops had been, not more so, and the difference is Brian Epstein.

After touring ended, a change in relations was inevitable; breaking up was not. Without “making it” keeping them interested and touring keeping them busy, what The Beatles needed most was someone within their camp who was smart enough to help them figure out a new way to be Beatles. While Epstein was alive, this meant John going off to be in How I Won the War (and write “Strawberry Fields”); the creation of Yellow Submarine, a Beatles movie without The Beatles that still manages to be great; them coming together in the identity-expanding Pepper, a Beatle LP with no moptop in sight; “All You Need Is Love,” casting the group as ambassadors to the world, a role they still occupy today; and Magical Mystery Tour, the world’s first midnight movie. Given what The Beatles did from August 1966 to August 1967—a vast maturing and self-redefinition which, taken as an aggregate, forms perhaps the lion’s share of their legacy today—it seems likely that the maturing and expansion would’ve continued, and held sufficient space for John’s love for Yoko, Paul’s restlessness, George’s desire to gig with others, and whatever Ringo wanted to do between albums.

But it was not to be. Let’s leave the final word to George Martin, whose speculations got me thinking in the first place. Speaking of Brian Epstein, Martin said, “He was incredibly honest and a little naive, but he entered a world that was totally alien to him. I don’t think the Beatles will ever acknowledge how lucky they were to meet up with a man who was devoted to them so completely and an honest man to boot.”

Media Mentioned in This Post:

The Brian Epstein Story

All You Need Is Ears

The Lives of John Lennon

Shout!

The Beatles

Can’t Buy Me Love

Magical Mystery Tour

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Rock and Roll Circus

How I Won the War

Yellow Submarine

(If you purchase via these links, Mike receives a small kickback from Amazon, which helps pay for the upkeep of the site. Thank you!)

Stigwood would have been an absolute disaster. He had everything but the most important thing: taste.

I remember when his film version of Sgt. Pepper came out, and Elton John (who couldn’t help but be brutally honest in interviews, perhaps inspired by John) called it “another Robert Stigwood piece of shit.”

Stigwood would have run JPGR into the ground. He loved his money, but he had none of the subtle understanding and appreciation that Brian had.

I don’t think Brian was going anywhere. I think John, with all his complaining and bitching, never would have cut Brian loose. Paul, as “cold-hearted” as his critics try to paint him, never would have cut Brian loose.

Brian couldn’t sleep. That was his problem. The horrible anxiety and tension he suffered with Diz’s blackmail and with being in the closet (a legally punishable offense!) kept him from sleeping at night. And pharmacology, being what it was back then, killed him, just like it killed many others of his generation.

Imagine Brian being happily married to a same-sex partner, managing the Beatles ventures, with no anxiety/insomnia/depression, with no Klein, no Diz, no Eastman quarrel… imagine the mid-70s and mid-80s Beatle albums we’d be talking about. This would be a different blog.

I agree with Michael that the trauma that Brian’s death caused has to be explicitly factored into the consideration of what might have been. Death of a family member is top of the charts for stress, and Brian’s death applied a huge stress to a situation that was already unstable. Minus that sudden event, whatever would have happened with Brian and the Beatles would at a minimum have happened more slowly. And any amount of braking on events would have helped at this point in the Beatles’ story.

Even before Brian’s death, it’s apparent that John is growing disenchanted with the band, for a range of reasons. Among them was the sense that he was no longer the unquestioned leader: Paul was outwriting him in terms of hit singles and quantity of songs, and George was also coming into his own as a songwriter. John said later that he felt the band was through when Brian died, that that was the real death knell.

OK, let me climb out onto the psychological limb here. I think John felt that way because, with the loss of Brian, he lost the person he perceived as his backup — the person outside the band who knew John as the leader in the early days, and whom John felt he could trust to have his corner. If you look at the people John was attracted to in the aftermath, Yoko and Allen Klein, it’s apparent that they’re both very strong-willed people who John felt were primarily loyal to him. I think John wanted to be the leader, but didn’t really want to run things. He couldn’t bear to let Paul run things, because that was too much of a threat to John’s leadership.

I do think it’s possible the Beatles would have demoted Brian, and that Brian’s instability could have caused more problems. But I also think that his mere presence would, as Michael said, have altered events, easing them by allowing the band some room to breathe and consider. When Brian died panic mode set in, especially with John.

Annie’s got it right. From p. 178 of All You Need Is Ears:

Martin goes on to express his belief that Brian’s death was “pure accident.” If he’s right—if Brian was depressed, but not suicidally so—then it’s reasonable to consider that he might have gone on living, barring the recurrence of “accidents.” But it would have been a downhill slide. As a manager-entrepreneur, he’d have gone on to do what Col. Tom Parker did after Elvis cut him loose: nothing.

He’d have advised the Beatles strongly against forming Apple (as anything other than a tax shelter, that is; none of this “Western Communism” octopus). They’d have ignored him. They’d have offered him an executive position; he’d have been too proud, and smart, to take it. He’d have struck out on his own, pouring his all into Cilla Black and lesser lights, passing popsters unworthy of his obsessiveness or the audience’s lasting attention. This would have palled for him eventually, and in any case, the mad rush of pop culture toward the new and away from the old would have left him behind.

It’s better to speculate on the life he’d have found or made for himself outside of the Beatles’ shadow, meaning, out of the pop world altogether. The sexual revolution, even in its stunted, compromised eventuality, might have saved him. He’d have come out of the closet, finally, and in the happiest scenario, become a grand old gay icon, turning up on BBC panel shows with Quentin Crisp and Angus Wilson to share laughs and horror stories about the bad old days before the passage of the Sexual Offences Act (a mere month before Brian’s death).

He’d have been famous for his past, not his present, for what he once did, not for what he parlayed it into. But that’s true of the ex-Beatles themselves, come to think of it, and it’s still a far happier ending than the one he found—or that found him. Who among us wouldn’t, if we could, rewrite history, reverse time, move mountain and cloud to give him that?

Mike, I think your analysis is as astute as always, but I respectfully differ, as can be read above, with your conclusion that Brian would have run Apple, or even wanted to run Apple—mainly because I can’t underestimate the role that Brian’s mental and emotional instabilities would have played in such an ongoing arrangement.

Neil Aspinall could run Apple efficiently and intelligently because there’s never been any indication that he was anything more or less than a highly skilled accountant with a truly extraordinary degree of personal loyalty to the Beatles as people, and to “The Beatles” as an enterprise. He went to business school, had no spectacular neuroses and zero use for drama, and, not of least importance, was able to learn from all of Brian’s mistakes. (Can’t you just see him watching Brian negotiate with Ed Sullivan and Sid Bernstein and Tito Burns and all the others, taking mental notes as he lugged suitcases and kept papers straight?)

Brian had none of those qualities. He was unstable, dramatic, not a skilled negotiator or bold manipulator (whatever his visionary gifts), and the Beatles were entering a period where their personal and corporate relationships were defined, as much as anything, by a persistent intractability all around, a chafing at compromise. I do agree with Spitz’s analysis that Brian had become a figurehead by the time of his death. Any ongoing stewardship of the Beatles’ affairs by Brian would have been fatally infected by his own instability and the Beatles’ unwillingness to be diverted from their more expensive and wasteful whims.

As for Stigwood, recall the moment in the Brian Epstein Story documentary when Paul says the Beatles threatened, if saddled contractually with Stigwood, to record nothing but off-key renditions of “God Save the Queen.”

Gosh, maybe I wasn’t as clear as I’d hoped to be in the post. “Apple”–which was Brian’s idea as much as anyone’s, given that it was a business solution to a business problem that was only later made into a hippie fantasia–that entity would’ve been something different, with Brian at the helm; maybe 50% hippie fantasia, and 50% properly run business. Even 75/25% would’ve been good enough to keep Lennon from freaking out and bringing in Klein–who never ever EVER would’ve touched The Beatles if Brian had lived.

Think about it: you have your old manager, who guided you to the pinnacle of wealth and fame. He’s still around, pining after you in fact. Then you have Klein…and the Eastmans…and so forth. Anybody can see that mess a mile away. Klein’s involvement was only necessary–Lennon only made that phone call in January 1969–because Brian wasn’t there. And even if Lennon had brought in Klein, do you really think the others would’ve picked him over Brian? Eastman, sure–Paul’s married to his daughter. But the guy who they shared Beatlemania with? Not likely.

So Brian wouldn’t have advised The Beatles against forming Apple; he in fact was the driver FOR forming it. What he would’ve done is kept them from blowing their fortune on it, which they only did because he died and they didn’t have anybody handling that stuff for them. But they didn’t want to be businessmen, not for a second, and that’s why they handed Apple to their roadie and turned it into “Western Communism.” Apple without Brian was a business solution that wasn’t run like a business, so it lost gobs of their money. This outcome–like the Klein/Eastman fight–was entirely predictable. (Unlike, say, Setlaeb, which was an ad-hoc solution to a unique situation.) Brian was great at managing and building the Beatles’ brand, and the things he did are still in force today; what he wasn’t good at was getting his pound of flesh from EMI, or sleazing around with various gonifs. That maybe shouldn’t be seen as a bad thing; when The Beatles were managed by Epstein, they were hugely successful, hugely respected, and blemish-free in the eyes of the law. Yes, they got screwed on royalties, but they cranked out a huge amount of product and made it up. When they were managed by Klein, they made more per LP, stopped functioning and lost billions in potential revenue, as well as spent millions on lawsuits that were nothing but bad news. That is TERRIBLE artist management, and that’s something that people like Goldman never address. The Beatles thrived under Epstein; they did not under themselves or Allen Klein.)

So Apple would’ve been different, just as MMT would’ve been different, and so forth. Even 75% hippie fantasia, Apple wasn’t a bad idea (cf The Gap here in the US, launched in 1969), it was executed simply dreadfully; and because it was executed so dreadfully, J/P/G/R viewed it with more and more distaste–as a millstone that somebody else created when, in fact, it was 100% them.

The Beatles best work was never 100% them. At least 25% of it was the taste and follow-through of people who specialized in taste and follow-through. People like Brian, and George Martin, and Richard Lester, and so forth. The reason Klein was a crappy manager was that he was only interested in currying favor and getting his percentage, when J/P/G/R needed—as we all do, sometimes—someone to say, “That’s a bad idea.” Brian could do that, and even when he was wrong (as with “brown paper bags for Pepper”) it was a much better creative environment than what followed. And that good creative environment made The Beatles’ fortune, and reputation, not Klein’s better royalty deals.

To assume that post-Pepper Beatles would’ve been the same if Brian Epstein had been walking the earth, rings utterly false to me. It overvalues the role of J/P/G/R, understates their generally decent sense of what’s good and what’s shitty, and understates their ability to flake when things got tough. Apple and MMT were both projects that started well, but crashed after the adult in the room, died. Even with Brian being dopey as a haddock and semi-functional throughout much of 1966 and 67, he was still much better than any Beatle at running a project, and you can see that by what came about under the late period of his management. Even IF Goldman’s right and The Beatles would’ve been enraged by the “secret 25%” in the EMI deal (no evidence that they were, even though that 25% must’ve passed to Brian’s heirs), it’s almost impossible to think that the practical McCartney, the toil-averse Lennon, and the penny-pinching Harrison wouldn’t have turned immediately to Brian after MMT had stunk, or Apple started really leaking.

So George Martin, God bless ‘im, is in the minority on this. I agree that Brian Epstein would’ve wandered the earth like a hungry ghost if he’d been fired by The Beatles, but I don’t think he would’ve been fired–or if he had, he would’ve been J/P/G/R’s very first phone call at the sign of trouble. Because in the end, none of them wanted to do what Brian could do, and they needed somebody to do it.

Devin, our comments crossed in the ether. This is all supposition, so I can’t disagree with the basis for what you say, but my perusal of the sources this morning suggested to me that Brian’s death was either accidental (likely) or murder (unlikely but I suppose possible), and not the foreordained outcome of his mental and emotional instabilities. Which, to be sure, had existed in 1962-1967, the period where he achieved more success than any manager in the history of popular music. But let’s say they were worse, and let’s say they were never going to get any better. Flawed as he was, Brian had to bring something to that party, and the more I manage projects and start businesses, big and small, I think he brought a lot. Branding, for one thing, he was an absolute genius at. He also had an uncanny sense of who to get involved with, and who to avoid; and a vast network of connections in the higher reaches of British society. This are tremendous skills. Think he would’ve been able to get somebody from the English art world to direct MMT, somebody who would work with Paul on translating his vision, just like Peter Blake and Fraser and Michael Cooper did for the packaging on Pepper? I do. And if that happens, MMT is a whole different ball of wax. The Beatles believed in DIY, but they knew its limits, too. John wasn’t putting his home tapes on Beatle records…until after Brian died, his life went to shit, and he reinvented himself. The last came about from the first two, IMHO.

But where I think we differ in a more fundamental sense is this

“the Beatles were entering a period where their personal and corporate relationships were defined, as much as anything, by a persistent intractability all around, a chafing at compromise.”

A good point excellently expressed, but I think it goes less far than you do. First of all, there’s a real behavior change pre- and post-India. “Why” has been debated on this site for years and will continue to be. John, especially, undergoes a massive shift–which I think would’ve been softened by the presence of Brian Epstein. You may disagree, but I think Brian played a foundational role in the adult John’s emotional life, and vice-versa.

The Beatles had been impossibly famous for years, headstrong for years–yet the chronology is irrefutable: when they were managed by Brian, for all his flaws, The Beatles maintained a balance between creativity and license that has been unmatched in the history of group creative endeavor. And almost from the moment he died, that balance went out of whack. That’s all we know for sure. My belief is that, however Brian did it–and we can’t know how it worked, because we weren’t privy to it–I think it’s more likely that the positive balance would’ve been more durable and more resilient if he’d lived. To argue otherwise seems to suggest that the later history of The Beatles was foreordained, or “bound to happen” and that’s just not so. Did things have to change after the group stopped touring? Yes–and they did, almost immediately, and to the great benefit of the material. The negative ramifications only seem to hit after Epstein dies, and that’s too clear not to note.

I too find it hard to believe that the Beatles would have, per se, fired Brian, but that’s not exactly what George Martin says. They wouldn’t have fired him; they’d have said, “We don’t want you to manage us any more. We don’t need a manager any more. We want you to do other things.” I believe, as I suggested, they’d have offered Brian an executive position, at very top echelon no doubt, but decidedly a demotion from the Supreme Arbiter of Affairs he’d previously held.

I never said the Beatles’ trajectory would have been the same if Brian hadn’t died. But whether it would have turned out better is something I have a hard time imagining, except as a compelling fantasy. Love is always in short supply, and the Beatles would have benefited, as any of us benefit, from having people around who have known us at our smallest and biggest, best and worst, who have known us before we became whoever we are. But big bad changes were in motion in 1966-67, and given that they were gaining momentum up to the moment that Brian died, I don’t believe they happened because he wasn’t there. Those things were, as I stressed above: 1) the Beatles’ increasing intractability; and 2) Brian’s increasing instability.

I should be writing this in outline form, but:

The scenario in which Brian successfully manages Apple—even as a much smaller, more focused enterprise of the kind he evidently discussed with Paul (there’s even a mention of “The Apple” on the back of Sgt. Pepper)—presumes that a) the Beatles would have allowed Brian the autonomy they’d given him at first, even at the precise moment when they’d come to believe, foolishly and flakily, that they were capable of handling their own affairs; and that b) Brian would have shaped up, kicked his various addictions, ceased to be debilitated by depression and ennui, and been happy with a much more compartmentalized position in the Beatles’ hierarchy. It means overlooking, or drastically minimizing the importance of, 1) and 2), both of which were on the wax, not the wane, in ’67, and investing faith in a) and b), which as far as I can see slights the truth as it was developing prior to Brian’s death.

To validly entertain a happier outcome (and Mike, your outcome is really quite, quite happy) is to assume a lot of felicities of personality that aren’t in the record. To assume, for instance, that John wouldn’t have had any problem with Brian and Paul double-teaming on Apple is questionable. He felt enough resentment just watching Paul try to run things; to be boxed out by both of his erstwhile worshipers (and knowing John, he’d have taken it that way, regardless of their efforts to involve him) would have been unendurable. And to guess that Brian might have ameliorated the Yoko Situation by giving John added support is to impute to Brian a fearlessness where Lennon was concerned, a willingness to brave his most ferociously guarded emotional territory, that to my knowledge he had never shown in life.

To say it was “inevitable” that the Beatles break up is not, in this case, to “excuse bad behavior,” though to say it wasn’t inevitable may be simply to wish bad behavior didn’t happen, and that people don’t change or sometimes grow inward, like the roots of certain trees, in gnarly, knotty, destructive ways. Brian was in serious trouble the last year of his life, mentally and emotionally. The Beatles wanted, foolishly and flakily, to control of their own business. Any scenario that doesn’t take these clear facts into high account, and instead presumes that everyone would have grown up, and grown together, in only the best, most sensible, most far-thinking ways, is a scenario that doesn’t deal with the toughest questions.

Excellently argued as ever, Devin, and you almost convince me, but for several points that I think are worth mentioning:

Supreme Arbiter of Affairs

Brian had already been demoted from “Supreme Arbiter of Affairs,” years ago. The Beatles themselves were already making all the musical decisions, having final say on the packaging (they were the ones that chose the distorted Rubber Soul cover, for example; and their old chum, not Brian’s, illustrated Revolver). J/P/G/R’s taking the reins may have contributed to Brian’s depression but it had already happened, long before August 1967.

Intractable?

And this timing, for me, casts your “increasing intractability” question into doubt: what where The Beatles planning to do in 1967, or in fact did before the release of “Two Virgins,” that came anywhere close to the Butcher cover? That was a direct chomp from the hand that was feeding them, just as their manager was renegotiating their deal. Interestingly, I just found out that it was Paul who pushed for the cover, saying it was “our statement on the war.” If you want to say that the LSD kerfuffle was them asserting a new desire to speak their mind, isn’t John’s “Jesus” comment (March ’66) and non-apology (August ’66) the exact same behavior? I realize that the conventional reading is that the end of touring gave them their head, but their behavior seems to be pretty consistent through ’66 and ’67. That’s a stable level of petulance, or stubbornness, or artistic self-direction, call it what you like, from at least late ’65 to the return from India. It’s only after the return from India that this “intractability” is turned on each other, and I happen to think that Brian Epstein would’ve softened that.

But whether it would have turned out better is something I have a hard time imagining, except as a compelling fantasy.

Better than the unquestioned leader of the group going through a breakdown, getting a divorce, replacing his main collaborator with a Japanese conceptual artist, and then spending the next 18 months sabotaging the group while navigating a serious heroin addiction, getting busted for drugs, and incurring the wrath of the US government? You can’t imagine 1968-70 being better than that? To me, that is just about as bad as it could get, except for one of them actually dying. Whether it was good or bad for Lennon himself, that trajectory was terrible for the group, and the only way it’s not terrible is if one takes the breakup as a foregone conclusion. Which I don’t. As we’ve seen with other groups, there are lots of ways to keep working together. I believe the presence of Epstein would’ve helped them figure that out–at the very least.

a) the Beatles would have allowed Brian the autonomy they’d given him at first

The Beatles did not want to be businessmen. Commerce bored them, which is why they had to turn Apple into a shop-cum-label-cum-commune—and even then they lost interest within six months. Running Apple, Brian would’ve had the same autonomy he had negotiating with EMI (“you do it, we don’t want to”), with the same results—some good, some bad, but none of The Beatles would’ve spent a moment in that morass. You don’t think the late history of The Beatles would’ve been better without the endless business meetings, and the Eastman/Klein fight? Really? Putting your pal who’s an accountant in charge means you’re still in charge; putting Brian in charge (and with Brian would’ve come some real City muscle, real City lawyers, etc) means you can concentrate on the music while he concentrates on his percentages. That is, what had worked beautifully for the past five years. Keeping John and Paul happy was what Brian did.

Instability

As to Brian’s instability increasing or decreasing, I think that’s somewhat unknowable. He had attempted suicide in late ’66; by August ’67, things seems brighter for him. On the other hand, he displays an uncertainty about his identity in ’67 that is worrying. On the third hand, the idea that he would leave his mother alone after Harry’s death seems unlikely. Add to this the decriminalization of his sexuality, and one can be forgiven for thinking that there was a corner being turned, or had been turned. I mean, was Brian’s drug use more serious than, say, John Lennon’s at the same time? Or in mid-’68? The only difference to me is that Brian was unlucky and John was lucky–and we don’t know how many close calls John had, not by a long shot.

The Yoko Situation

As to John and Yoko, I think it’s a fair assumption that Brian would’ve shown them at least the level of friendship that Ringo did–and that would’ve gone some way towards improving the Situation. How could it not have? And it’s precisely because I think Brian loved John and didn’t want to lose him that he would’ve done anything to make him happy re: Yoko. If you posit that Brian lives, and Yoko comes on the scene in the same way (which I’m not sure happens, but OK), then Brian making Yoko feel more welcome and comfortable is obvious—in other words, he would’ve done what Klein did from 1969-1971 or so, not because he wanted to worm his way into the Beatles’ coffers, but because he loved John (and the group). Accommodating a Beatle’s complicated romantic life…once again, that’s what Brian did.

a scenario that doesn’t deal with the toughest questions.

The TL;DR

Were The Beatles exerting a greater degree of control on their business affairs from mid-66 to Brian’s death? No. They were exerting a high level of artistic control, but that had been in place for 18+ months before Brian’s death. They ended up sitting in business meetings from August ’67 onward, yes, but that was because Brian had died. You seem to think they wanted to do this; after the first couple, I think they did it out of necessity and paranoia, because none of them had shown, was showing, or has shown, any interest in commerce qua commerce.

Was Brian in serious trouble the last year of his life? Clearly so; but by the time of his death, several circumstances suggested that he was on the road to recovery. And even if he wasn’t—even if that light at the end of the tunnel was an oncoming train—we have an example very close at hand of someone as emotionally damaged and fragile as Brian, who had a much stronger drug habit, who an unhappy romantic life and great misgivings about the choices he’d made, who was under even more pressure than Brian was in August 1967. His name was John Lennon, and he went on to quite a successful and productive life.

So: asked and answered, counselor. Your witness.

Mike, this last post was written without regard to your posting just before. I have to go running now before it gets too dark to see, but I’ll be back. (That’s a song title, isn’t it?)

Hee hee hee–I can’t wait to see what you say, I wrote a whole other long thing!

You go run, I’ll go meditate and we’ll meet back here!

Really enjoying your back-and-forth, Mike and Devin. Still thinking all this through.

But I do want to say “Amen” to this, Mike: “The Beatles’ best work was never 100% them. At least 25% of it was the taste and follow-through of people who specialized in taste and follow-through. People like Brian, and George Martin, and Richard Lester, and so forth.”

That quasi-parental figure who provided the follow-through was crucial to the Beatles’ stability; it kept any of them from feeling the need to play that role, and kept the four of them of the same category, if you will. Once there was a vacuum there — and even with Martin around, the day-to-day role was empty once Epstein died — the die was cast. That’s my sense, anyway.

Looking forward to seeing what else the two of you have to say!

Just want to echo Nancy and Craig and say I’ve really been fascinated with this back-and-forth. Thanks for all the interesting analysis, Devin and Mike!

Like Nancy I also zeroed in on Mike’s point about 25% of the Beatles genius being contributed by those who “specialized in taste and follow-through.” Really good point, beautifully put.

It’s Shark Week at Hey Dullblog. Both Mike and I have our teeth deep in the idee-fixe, and neither will let go.

Certainly the late history of the Beatles would have been better if all those bad things hadn’t happened. That’s not the point of this game. The point is, what trajectory makes most sense given the various kinds of momentum that were in play when the fact of history that begins this discussion, in fact, occurred? That being, the fact of Brian’s death from a drug overdose? (Incidentally, to equate Brian’s pathologies with John’s seems to me a classic apples-and-oranges comparison.)

As you point out, Mike, with the butcher cover, the Jesus comment, the Vietnam statements (and Sgt. Pepper not going out in brown paper bags), the Beatles had been moving in the direction of managing themselves and their public image for a long time. There’s no reason to imagine that that trend would have ceased after Pepper vaulted the Beatles to an unprecedented pinnacle of popular, intellectual, and cultural esteem. There’s even less reason to imagine that it would been so decisively reversed, in the direction of harmony, commonality, and fiscal responsibility; and still less to imagine that Brian would have been the one to reverse it, in the Apple context or in any other.

Once again, Mike, to argue your scenario is to invest Brian with powers of focus and recovery, and the Beatles with attributes of acquiescence, that were almost completely gone by mid-1967. Not to insult you with the obvious, but they were not the same people they were in 1962, and your argument presumes that they could have found, or fought, their way back to something that looks very much like that starting point—and that they would have cared to. To imagine that Brian could have whipped the boys into shape, kept the interpersonal peace, and managed Apple as well as someone like Neil Aspinall is to picture all of them “getting back to where they once belonged”—and we know how well, or conclusively, most such projects were turning out in the late 1960s. It is to picture all five of them, in their various states of damage, addiction, egotism, depression, distraction, and fractiousness, exercising degrees of focus, follow-through, and discipline that were beyond their abilities or desires to summon. (Making music is a different kind of discipline, a different kind of focus, one that they lost only a few times, and then only briefly. We’re talking here about the Beatles’ public presentation and business interests, their extra-musical intercourse with the world outside, which had always been Brian’s realm.)

Of course the Beatles didn’t want to be businessmen—not in anything more than the shortest term. Even John knew this when he said at the NY press conference, “Now we’ve come back [from India] to play businessmen.” Some part of him, not too deeply submerged, knew it was a charade, a stunt they were running because they had the means. (And because it made fiscal sense—at least at first, at least as a tax dodge.) But the Beatles had long passed the point of wanting people to tell them what they couldn’t or shouldn’t do. They wanted to do what they wanted to do when and for how long they wanted to do it (Apple, Zapple, peace stunts, Getting Back to Tunisian amphitheaters or London rooftops), and they wanted the people around them to facilitate those whims. That calls for functionaries, not managers, and certainly not visionaries. Even if Brian had found his “Reset” button and pulled his act together, there was no longer a place in the Pepperland of Beatle ego for the kind of manager he had been, or the manager (and this is me making a subjective conclusion about his predilections) that he would have wanted to be, had he lived.

Even in courts of law, rebuttals don’t go on forever. Having stated my case, I withdraw, in the hopes that Nancy and others will weigh in on what has been, since about 1970, one of the essential Beatle what-ifs.

Brian was a great manager on so many levels, all of which have been covered in this discussion thread. It can all be summed up in one word: visionary.

But he had six qualities that I think would have made him a poor corporate head.

1/ He was a bit of a micro-manager, lacking the ability to delegate duties.

2/ He totally flubbed Beatles merchandizing.

3/ He had no idea how to protect the Beatles’ assets from the taxman.

4/ He liked being creative and famous in his own right. In other words, he was a “celebrity manager” rather than a manager of celebrities.

5/ He managed more groups than the Beatles, which probably helped spread him way too thin.

6/ He had personal issues that ate at his self-esteem

I just can’t see a man like that doing a great job as the head of Apple. In fact, when the Beatles stopped touring, instead of straightening out the business end of everything or focusing on his other groups, he fell into a depression because he didn’t feel needed by the Beatles. Then he started up a theater concern that tanked. Maybe he wanted to get into theatrics because he wanted to be more creative and less of a suit.

Let’s say that Brian managed to become the ideal suit. Let’s say that he managed to get it together to manage Apple. There was still several issues that he would have bumped heads with the Beatles over.

1/ Apple was filled to the brim with the Beatles’ buddies. Could Brian have fired these incompetents without pissing off the Beatles? Sure, Klein eventually did, but that was only after these friends let down the company.

2/ Could Brian have kept the Fool and Magic Alex from ripping off the group?

3/ Could he have kept J and Y from doing crazy things that hurt the corporate brand in terms of being taken seriously, such as posing nude?

4/ Finally, there’s Yoko. If she thought that the Beatles were a bunch of bourgeoisie poseurs, would she have felt any more positive about Brian?

Aw, Devin, don’t stop playing now. It’s just getting fun!

That’s not the point of this game. The point is, what trajectory makes most sense given the various kinds of momentum that were in play when the fact of history that begins this discussion, in fact, occurred?

No, the point of this game—at least the game I’m playing—is an exploration of the unanswerable question, “What if Brian Epstein had lived?” What you’re calling “the point,” is actually an approach, a technique. But it’s far from the only valid technique, and it doesn’t necessarily give the best answer, especially when applied at the individual or small group, level. In fact I’d say it almost never does.

For example: from 1940 to 1968, John Lennon’s “type” was subservient, slightly passive, blond, English women. If we charted all the datapoints (hi ladies!) that would be the trend, and given the sample size (huge), it would seem utterly predictive. And yet that trend is flipped on its head in May ’68.

Trends get less and less predictive the closer you get to the individual (or small group) level. Yet contemporary people love using them to predict individual behavior. Why? Because they feel data-driven, which to us feels scientific and smart.

Being brutally reductive, there are two approaches to history: One emphasizes individuals, and the other trends; the former treats history as an art, the latter as a science. The former has been largely out-of-favor in the 20th Century, as historians rushed to upgrade themselves from mere storytellers, but I personally favor the former, because I think the latter understates randomness, folly, and agency. And I think trend-based history is 100% opinion—facts arranged by biased smart people after the fact to create “trends” that push all us little humans around—while the former is about 75% opinion, with 25% being a highly valued record of what we know the person did, and said, and thought.

In this particular discussion, “trends” are too slight to be predictive. The “trend” of The Beatles meticulously controlling their packaging and public image apparently went out the window with MMT, YS, or Klein’s Hey Jude album—three of the next four albums after Brian’s death. Does this mean the trend reversed from Rubber Soul, Revolver, and Pepper? No—because all these decisions were functions of individuals working in a complex interrelationship governed by emotion, personality, convenience, etc. Not trends.

So we can say, generally, that The Beatles were taking more control of their own affairs as they aged; but we can’t really use that to predict behavior on the granular level. The other trends you name are also similarly uncertain—not useless, but not predictive, and (IMHO) impossible to isolate from events. Did The Beatles control their own business affairs after 1967 by choice or by necessity? You say choice and point to a trend; I say necessity and call it a reaction to Brian’s not being there. We KNOW my reason is valid—Brian wasn’t there—while your reason is a guess. A reasonable guess, but a guess.

My position is that the death of Brian Epstein had a decisive, and decisively negative, effect on the group. If one holds this view–which, to me, is so standard as to be canonical–it seems to follow that his presence (the premise of the post) would’ve had a positive effect on the group, particularly given that The Beatles most pressing problems from August 1967 to April 1970 were squarely in Brian’s realm: business dealings, and inter-group harmony. To argue otherwise I think would take extraordinary data, and I don’t think you’ve got it.

But really at issue here is, I think, two ideas of what Brian was, and what he did. I’ve had agents, and I’m a client with an intermittently intense vision of my own branding and packaging–which leaves me periodically when life intervenes. (Sound familiar?) I’ve actually turned down $25K contracts because I didn’t like the packaging. So I know something about these issues; you do, as well. That’s why I’ve never believed in Brian telling the Beatles what to do, even in the early days. I think he suggested, handled money, fielded phone calls–and let them do the rest.

I personally do not believe for a second that Brian was any sort of Svengali. I do not think for a second that he ever made The Beatles do anything they really didn’t want to do. From 1962 on, it was a partnership with The Beatles—the client—having the final say. I think Lennon later laid on Brian things that he felt were uncool; but the idea that Brian Epstein pushed around John Lennon for one second flies in the face of everything I know about both men. And about who has the power in artist/manager relationships. The Beatles always had the power, and they exercised it consistently during Brian’s tenure. As they gained experience they began to have opinions–“We want to do this, we don’t want to do that”–but Brian was always following their lead, not vice-versa. That’s what a representative does.

So if Brian wasn’t a Svengali—if he was a kind of benign collaborator: a business intermediary, and a branding consultant, and a confidant and a fixer—there’s no reason that he couldn’t continue doing those things, had he lived. In fact he WAS doing those things from August 1966 to August 1967, at a time when the Beatles’ business, brand identity, and mode of living changed drastically. All these things changed much more drastically between August ’66 and August ’67 than they did in the next year.

It’s easy to argue that Brian couldn’t or wouldn’t have wanted to run Apple, but what “The Apple” came to be was materially affected by Brian’s death. Apple was not planned as Western Communism before Brian’s death, nor would it have become the total free-for-all in ’68 if Brian’s heavies had been involved. To suggest that Apple would’ve been a trainwreck no matter what because The Beatles would’ve insisted on running it themselves no matter what—and that wreck would’ve inevitably led to Klein, and so forth and so on—well, that line of thinking only sounds attractive because it’s not really prediction. Which IS the point of this post, to me at least.

I’ve really enjoyed this, thank you; keep talking if you have more to say.

Mike, you’re probably right that ours is primarily a difference in approach, and I think it’s not just to the immediate question but to all aspects of the Beatles’ history (and to history, full stop, for all I know). I’ve always thought our emotional-intellectual differences explain why you dislike the White Album so much, versus why I love it: You deplore the decay and divisiveness captured and expressed in that album, while I find those elements inherently dramatic—not to mention inescapable, since they remain squarely before us in the grooves of the record. What, then, do you and I, each in our singular perception, do with what is inescapable? From your approach, WA becomes a “hot mess” of self-indulgence, ego, and bad vibes, the two-disc monument in aspic to the cancer that killed the Beatles. From mine, it is the sound—brutal, beautiful, even noble—of the group’s shared musical spirit fighting to survive, and surviving, though their communal spirit is dying. Neither of us is right or wrong, of course; we’re just forming wholly different apprehensions based on how we find ourselves—through psychological inclination, I’d guess, more than choice—approaching, interpreting, visioning, and re-visioning historical materials.

The “what if” game is a related but different phenomenon, in that it seeks to, let us say, escape the inescapable—to assume that what happened didn’t actually happen, to imagine the landscape along the road not taken.

A “what if” game that has been played in print and in discussion for roughly 150 years is this: “What if the South had won the Civil War?” I’ve become more familiar with that one down here in Gettysburg, and find that not only do all players, historians both professional and amateur, take the “game” with utmost seriousness, but all concur on its “point” and ground rules. The point, as these players define it, is simply to develop the scenario of greatest historical plausibility. One ground rule, perhaps the starting one, is that all known data up to the speculative “cut point” (the South’s surrender, Brian Epstein’s death) is assumed to be still in place. Another is that you may project forward from that point only in ways that do not violate, and in fact tend to support, the trajectories formed by that known data.

Still another ground rule is that you’re not allowed to project backward from a desired outcome. For instance—bear with me—it’s been suggested that if the South had won, Robert E. Lee would have been put up for President, as his counterpart, Ulysses S. Grant, was in fact. Like Grant, Lee would have accepted the draft, though he wouldn’t have wanted the job. Like Grant, Lee would have won. Here’s where it gets interesting: Would Lee, per Lincoln, have worked to abolish slavery as President? It sounds plausible: He’s known to have favored liberating and educating slaves in certain circumstances, and in a letter he called slavery “a moral & political evil.” Certainly, anyone who admires Lee would militate for this interpretation—would desire this outcome. But most historians override it by invoking the texts and beliefs of Lee’s religious and economic class to the effect that slavery, though it was a heinous institution, was in fact willed by God, and that it was up to God to determine when it should end. Additionally, Lee, unlike Lincoln—let alone Frederick Douglass, John Brown, or other rabid abolitionists—had never been in a position to witness slavery at its inhuman worst. Therefore, say these historians, the more plausible conclusion is that no, “President” Lee would not have agitated for abolition—would not have done what we now consider the right thing, though one’s admiration for his other qualities, along with our modernist desire to “complicate” history, make it a difficult conclusion to accept.

There are probably as many ways to play the “what if” game as there are people to play it. The one defined above is the one that my mind snaps to most readily, and that I take for granted unless the terms are defined otherwise. Another approach, perfectly valid as a game but quite different, is, as I’ve termed it, projecting backward from a desired outcome. I believe that’s the approach you’re taking, Mike: You want things to have turned out better than they did, and so you begin from that position of wanting. You proceed from the wish, from a projected future, rather than from the “cut point.” And because of the wish, you find that cut point—Brian’s death, and the year or at least months leading up to it—to be far richer with signs of life, signifiers of hope, than do I.

At least, that’s how I see this whole thing. I don’t even need to say out loud, though I will, that you will not see it that way, and that you will answer everything I’ve said at least as articulately as I have said it. The thing is, in the case of Brian Epstein and the Beatles, I want those happy (or at least happier) outcomes to be true just as badly as do you. But unlike you, I just can’t see them being true—not from my approach, not with my ground rules, not the way I’ve always played this game.

Devin, your comment puts me in an uncomfortable position, because you’ve made this discussion about me and you personally. To rebut your main point I’d have to discuss my own psychology, which I don’t care to, and opine about yours, which seems presumptuous. So I’m not going to engage in that way, if you don’t mind.

It’s natural given your location, but I think the counterfactual you raise is misleading. The question “what if the South won the Civil War?” is HUGELY triggering—it would be impossible for a contemporary American, white or black, Northerner or Southerner, to avoid bringing massive amounts of really hot emotional baggage. I don’t really think that “what if Brian Epstein lived?” packs the same emotional punch, even for commenters on a Beatles blog. And I’m not even suggesting that The Beatles wouldn’t have broken up eventually; I’m just saying that it wouldn’t have gone down as it did. This doesn’t seem like a very heavy assertion.

I believe that what broke up the group were temporary issues that could have been resolved—matters of business, working methods, and personal interaction that creative groups can and do resolve—and that the presence of a functional Brian Epstein after 1967 would’ve helped that process a great deal, because business and personal interaction were the precise areas he worked in. I think that’s an utterly defensible point; but just saying THAT isn’t a very fun post, is it? It’s more fun to get into the details, which I did.

Your counternarrative is essentially “the history of The Beatles would’ve been the same, except that Brian would’ve gone on chat shows.” Well, really dig into it—would he have become a chat-show host? (not impossible!) The David Frost of music? Would he have been a fixture at the Continental Baths? Would he have then discovered Bette Midler? Would he have died in John’s arms, on the dance floor of Studio 54 from a massive cocaine-induced heart attack? It’s all conjecture, so by all means conject!

What’s informing my opinion about this is 20+ years of running creative groups; having a writing partner; having to handle lots of contracts; setting up and taking down businesses; and (not least) my current opinion about John Lennon’s mid-68 breakdown, which I think was caused by a specific, little-known but treatable physical/psychological condition. Of course I would’ve preferred a better ending to The Beatles’ story; but that’s only a part—and a small part—of my opinion on this matter. And my opinion is less fun than the creative writing exercise, which I’d love to hear from you—and everybody else!

Mike, you said “John Lennon’s mid-68 breakdown, which I think was caused by a specific, little-known but treatable physical/psychological condition”

I’m very curious what you think that condition was. I’m intrigued that you say it was physical and psychological. I’ve heard others on this board suggest a possible untreated bi-polar condition. Is this what you’re alluding to?

@Sam, I’m debating the best way to present my conclusions, which I came to this summer after discovering a malady sometimes seen in beginning meditators who become determined to rush the process. It’s likely to seem bogus to people without any background in this area—gosh knows I would’ve felt that way, myself—but it fits so snugly with the chronology and Lennon’s behavior, that I find it quite persuasive at the moment. So watch this space.

I think it’s tough to judge what going on in John Lennon’s brain, especially after 1966; what was natural and what was chemical and what was neurosis and what was damage. Certainly he had periods of great creativity and focused attention, and we know he had periods of the reverse, but these are long, multi-year swings and I don’t know enough about manic depression to have any clue about that. I would be pretty confident in saying that he had an addictive personality, and a lot of the 12-step stuff seems to illuminate his family dynamics (and The Beatles themselves), but all these things have to be used very delicately, like an archaeologist brushing away grit from a jawbone, careful not to alter the specimen with the tool…

What do YOU think?

@Sam, I’m debating the best way to present my conclusions, which I came to this summer after discovering a malady sometimes seen in beginning meditators who become determined to rush the process…What do YOU think?

I honestly don’t know. We know he’d had tragedy after tragedy in his developing years… the death of loved ones (including Stu) and this grief caused stress on his nervous system. He was taught by Mimi (perhaps by example, seeing her handle her husband’s death) to stick your chin out and carry on. He wasn’t a Rory Storm, who imploded under crippling depression after some setbacks. John’s habit under pressure was to grin (I saw an example of this during a Beatle press conference directly after the “bigger than Jesus” clusterfuck. Paul and the others were clearly annoyed, and John put a grin on his face and stared at Paul. (Did Yoko call it his window face?)

I tend to think his breakdown might have been a rebound effect from quitting amphetamines. Something was clearly wrong, but not Brian Wilson, Rory Storm, or Syd Barrett wrong. Not that bad. I think he was made of stronger stuff than that.

Wow – that was an impressive back and forth guys. I very much enjoyed catching up on it all. Mike, you’re quite cryptic in your last comment. Perhaps saving the best of it for an actual upcoming post re John’s supposed breakdown? I hope so. Also, I think you might be taking Devins amazingly well articulated example of playing the ‘What if’ game the wrong way. He’s not comparing the emotional baggage or historical significance of the Beatles to the Civil war – he’s just providing context for how he has played and is playing the game. I tend to side more with Devin on this one. All signs (to me) point to Brian continuing in a downward spiral. I don’t see how, if he survived into September ’67 and onwards, he would have behaved any differently and thus been able to avert the breakup of the group. Alas, it is wonderful to think of a happier and more cohesive group that functioned as a whole into the ’70s.

Hey Mike, I’m sorry — I didn’t mean to personalize this in the wrong way. You’re right, it was about you and me, our differences in approach, but if the tones or implications were off, I apologize. Our responses to life-and-death questions are inherently personal, and when we get into back-and-forth on this blog, each response takes us a little closer to the bone of where we come from as individuals. It’s hard not to feel, and take, things personally at that point. That’s why I generally like to withdraw from these discussions after a few responses, and not get into the back-and-forth so much.

For what it’s worth, and to keep it brief: When I said comparing Brian’s illness to John’s was apples and oranges, I guess what I meant was that John’s addictions, depressions, etc. were offset by a combativeness, an ego, an unwillingness to ever give in that Brian didn’t have. John went out and made his fortune/place in the world; Brian had it given to him. John was angry, Brian wasn’t. John was a fighter, Brian was a negotiator. That’s why I think Brian couldn’t have made the recoveries John made.

@Craig, I’m glad you enjoyed it. Always good to hear your opinion.

@Devin, no apologizes necessary. I wasn’t angry or anything, I just felt an authentic boundary in myself and wanted to note it, so you didn’t think I was playing a rhetorical game. And I also wanted to prevent myself from putting any more words into your mouth which I felt was genuinely disrespectful and not fair. I always so appreciate your outlook, even when (especially when) it doesn’t jibe with my own. Any heat is the friction of ideas rubbing together; even “disagree” is too strong a word.

Not to beat this into the ground, but both of you seem to be hung up on whether it was likely that Brian would’ve survived and thrived; I agree as of August 1967 it seems not–though people can and do turn corners abruptly in areas of addiction and personal behavior. I’ve seen it happen, in both directions. And there’s that oft-quoted letter to Nat Weiss full of plans and signing off “bells, flowers, love” etc. He seemed to be reconnecting with life a bit, and I don’t think anybody who doted on Queenie as he did would’ve left her on purpose at that time, in that way.

Any process of recovery from addiction must have within it a positive reversal, and as long as Brian lived, that possibility existed. My post wasn’t about whether such a reversal was likely to happen, only what could’ve happened if it had. People’s lives shift in strange ways; in 1967, you could’ve made a fortune taking odds on John Lennon of The Beatles divorcing his wife and shacking up with a Japanese conceptual artist. That was a shift along the order of what Brian needed; as was Brian’s going to see The Beatles in the first place.

As to “apples and oranges,” @Devin, I would only say that what you describe reflects the stories constructed around each man. But as with all stories, they are oversimplifications of what each man faced and did, filling in a bunch of unknowables and making random acts seem foreordained by character. Just as Brian was plenty pugnacious—his hunt for a contract is nothing if not a one-man war against an entire industry—John was plenty pliant.

I don’t think John made any recoveries from any addictions, any more than Brian did; John didn’t OD, but that’s luck and body chemistry, not toughness or intelligence. Being (mostly?) heterosexual, John had a whole armature of societal support that Brian did not. The Yoko Solution was not available to Brian, and if it hadn’t been available to John, doesn’t it seem likely that he, too, would’ve ended up as a macabre cautionary tale?

Brian was born well off, but that can also be a shackle; Brian could’ve lived a nice little life in Liverpool, full of gentleman’s privilege, his gayness politely ignored, his Jewishness ameliorated by civic generosity and the right friends. To do what he did in 1962 took huge courage; we can’t see this now because it paid off so spectacularly, but for Brian to be who he had been, then do what he did, was more courageous than anything John Lennon did before divorcing Cyn and marrying Yoko. It took guts and drive and total commitment to something one knows to be right. And a willingness to be mocked and ridiculed and made an outsider, something that Brian’s gayness and Jewishness and Northernness made him painfully aware of. What was the 17-year-old John putting at risk by betting it all on rock and roll? Very little—school sucked, and conventional life didn’t fit him. Whereas when he started mucking about with The Beatles, Brian was running from a cozy, genial life that most people would’ve envied into—what? That doesn’t make Brian a saint or John less of a hero, it’s just my attempt to add some shading to the conventional view.

John’s fortune simply would not have existed without Brian—it would be nice to think that talent trumps all, but the only reason John’s violence and temper didn’t derail The Beatles in June 1963 (and countless other times we don’t know about) is because Brian cleaned up the mess. John was lucky in certain ways that Brian was not.

I think every life takes a lot of courage. Brian’s battles were, it seems, mostly internal. John’s should’ve been, but he sought external battles to distract himself. I’m not comfortable weighing either man’s courage and finding it wanting. I think they were more similar than different; that’s why they were so close.

Oh, boy. The only way to stop responding is to stop reading!

To clarify, I wasn’t making a comment on either man’s level of courage. Obviously it took very particular kinds of courage to be who Brian was at that time and place, and tremendous fortitude and determination to push the Beatles as he did. Nor can I disagree with any of the nuances or contradictions of both men that you point out, Mike. But don’t let nuance turn a conventional picture into its conventional opposite.

It seems to me that John stood to lose a lot more if the Beatles hadn’t happened — if he hadn’t succeeded in MAKING them happen, at least happen to the point where they could be noticed by a Brian Epstein. He didn’t have a family business and family money to fall back on. Nor was he so agreeable a creature that he’d have tolerated a long life of working for other people. Quite simply, what were his options? Besides rock and roll, he hadn’t found anything that locked into both his talent and his caring. Maybe art — but even there, he had zero patience for the classroom, the hoops and ladders he’d have had to go through to have a career in that world.

Arguably, Brian had at least as much support system as John had — not only his doting family, but close associates like Derek Taylor, Peter Brown, Nat Weiss, David Jacobs (his attorney, also gay). But a problem with self-destructive people is they will often use their support system merely to survive the latest crisis and get to the next one — not to move beyond crisis as a condition.

I don’t doubt for a second that Brian, despite being gay and Jewish, would have made the very accommodations with ordinary life that John couldn’t have — that he’d have made a contented life for himself if the Beatles had never come along. He’d have been screwed up, but no more so than many ordinary people we’ve all known. Can anyone doubt that the volatile ingredients of Beatle life (money, exposure, overall stakes) made Brian far MORE vulnerable as a homosexual, addict, and person of erratic self-image? That they put him far closer to the existential edge than if he’d stayed an unknown Liverpool furniture dealer?

I wonder if anyone has ever asked this question: If the Beatles hadn’t happened, would Brian Epstein still be alive?

Well, by all means don’t stop reading! 🙂

This is what you wrote, made me think:

But a problem with self-destructive people is they will often use their support system merely to survive the latest crisis and get to the next one — not to move beyond crisis as a condition.

Strangely, I don’t think of Brian Epstein as “a self-destructive person.” I think of him as a person addicted to pills and gambling and sex. These things are biochemical—craving hits of serotonin or whatever—suicidal tendencies are different. He had those, too, but I don’t think he had any greater desire to self-expunge than the next person, save for the horrible luck to be born gay in pre-War Britain. This could be an overly sunny view of him. Perhaps it is. But he was smart and resourceful and—just as Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr all struggled with addiction and survived—I’d like to think he could’ve as well. I reject the romantic idea of Brian as doomed—maybe wrongly. But it’s just never felt accurate in his case.

I don’t doubt for a second…contented life

However, this also does not ring true to me. Though I don’t think he was doomed, I think Brian shared John’s basic dissatisfaction with “ordinary life”—very common among addicts and surrounders, in my experience—and this hunger for something more, new, different, better, special was precisely what impelled him to do all the things he did. I think that’s what he was seeking—I think that’s what the vast majority of people in showbiz are seeking. But with excitement comes risk. Some people gamble and win; some people gamble and lose. The problem with these behaviors is you don’t know if you can handle them, until you do them. John could, just barely. Brian really couldn’t.

I think Brian Epstein had about as much chance of staying a Liverpool furniture dealer as John Lennon had of working as a clerk at NEMS on Whitechapel. What I’m pondering today is: John succeeded at the first thing he tried, and had the natural vigor of youth impelling him forward. Brian had lots of failure, and the weight of family expectations, and age, and no place in normal society. John’s gambit was deadly earnest, for sure, but he’d really never tried and failed, much less been hauled into court or overtly rejected or publicly humiliated. Brian had, and to wager the first bits of success and stability and esteem that he’d gathered on an unknown beat group…That’s something. It really does feel like John’s chucking it all for Yoko. And maybe it was getting what they thought they needed—what they craved—that was ultimately not so great for either man. What’s the old saying? “There’s no greater tragedy than answered prayers”?

[…] GERBER • In keeping with our recent spate of blather on Brian Epstein, I wanted to alert Greater Dullblogania about something that I am certainly getting for Christmas […]

Well, all, I must say, this discussion is highly intelligent, highly enlightening and most interesting from both perspectives.

However, as this is a question I, too, have pondered, I can’t help but agree with Michael, here. Brian Epstein was unequivocally a driving force in not only The Beatles brand, but in their lives as well. To have him taken from them not only devastated them emotionally, but in business of The Beatles. Lennon was nothing short of in shock. His bewildered comments upon hearing of Einstein’s death is more than proof of this. Coupled with the fact that he felt somewhat responsible, as he was the one to turn Brian on to pills.

In this interview clop below, John talks about Brian’s death and how he attributes it to the break up of The Beatles. There’s more to the clip than what I’ve transcribed here, but this is the gist:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=317yvBXrXjw

“We got fed up with being side men for Paul. After Brian died that’s what began to happen to us. After Brian died, we collapsed. Paul took over and supposedly led us, but what is leading us when we went round in circles? We broke up then. That was the disintegration. The Beatles broke up — after Brian died, we made the double album. Its like if you took each track off, and put all mine — and like I told you many times, it’s me and a backing group, and Paul and a backing group. And I enjoyed it, y’know. But we broke up then.”

Oh learning of Brian’s death he remembers: “We were in Wales with Maharishi. We’d just gone down after seeing his lecture the first night and we went down to Wales and we heard it then. And then we went right off to the the Maharishi thing in Wales, a place called Bangor in Wales. We were just outside a lecture hall with Maharishi. And some … I don’t know. I can’t remember. It just came over. Somebody came up to us — the press were there because we had gone down with this strange Indian — and they said, “Brian’s dead.” We were, I was stunned, y’know. We all were, I suppose. And the Maharishi — we went in to him and said he’s dead and all that, and he was saying ‘Oh forget it. Be happy.’ Fuckin’ idiot. Like parents, y’know. Smile. That’s what Maharishi said. And we did. We were along with the Maharishi trip. The feeling that anybody has when somebody close to them dies is a sort of little hysterical, he, he, I’m glad it’s not me, or something in it — that funny feeling when somebody dies. I don’t know if you’d had it. I’ve had a lot of people die on me. The other feeling is what? What the fuck? What can I do? I knew that we were in trouble then. I’ve never, I didn’t really have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music. And I was scared.”

He goes on to talk about Paul taking the reigns and almost wanting credit for keeping the Beatles together.

I believe Paul did what he did because he must have recognized that they did have contractual responsibilities that they had to fulfill, and he made that happen.

There is another interview (that I can’t find at the moment) where John admits that if someone didn’t call him, he wouldn’t call them. Even later in life he would only call his family, he said. He recalls that after they were deported from Hamburg the first time, he stayed a bit longer and jammed with other bands for about a month, and then finally came home. But he was home three weeks before he called any of the rest of the Beatles and they were all mad at him for not calling. He was the leader, but he was also (as it has been reported) a bit lazy. After Brian died, I believe Paul took over to make sure they met their contractual obligations.

Which brings me back to what if Epstein had not died. There would have been no need for Paul’s bossiness to surface so obviously and cause resentments, because Brian, whether as manager, or just as someone in their camp whose advice and guidance they were accustomed to taking, would have seen that their contractual obligations were met.