- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

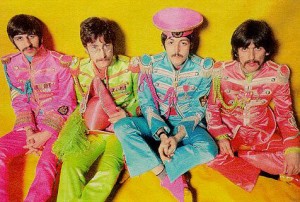

The original Mad Men. Look at that hat, for example; that’s MAD.

Did Matthew Weiner follow the structure of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in the recently-completed fifth season of “Mad Men”? Yi! News site contributor Emily Viviani thinks so, and has developed this thesis over three posts, the first of which you can read here.

Thanks go to commenter Craig for drawing the attention of Hey Dullblog to her pieces. — Nancy Carr

Viviani’s case

Some of the parallels Viviani draws are interesting (“At the Codfish Ball” as a take on “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”, for example), whether or not you buy them as intentional. Overall, the similarities fail to convince me that this season of “Mad Men” deliberately mirrored the album. But they do strengthen my convictions that “Sgt. Pepper’s” themes are universal and that the album is much darker than it’s often considered to be.

The link I’d make between this season of “Mad Men” and “Sgt. Pepper’s” is larger and much less tied to episode specifics. At the end of season five the folks at Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce are experiencing heady success, with the question being where they can go from here. And that’s the same question the Beatles confronted after “Revolver”: where do you go after you go straight up?

The act you’ve known for all these (five) years

The beginning of the end?

The Beatles re-presented themselves as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band just as the group’s seams began to show. It’s an album by a well-established band (“the act you’ve known for all these years”) that is beginning to wonder, however tentatively, if its best times are behind it. Sgt. Pepper’s band is portrayed as a revival act: they learned to play “20 years ago today.”

In retrospect, “Pepper” was the beginning of the end for the Beatles, however brightly things shone at the time. It’s looking to me as if the same will be true for Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce.

At the end of this season the firm is on its way up — literally — but I got a bad feeling about the direction things were heading. Similarly, “Pepper” brought the Beatles an unprecedented level of acclaim, but it exposed and widened a crack in the band’s foundation. The Lennon/McCartney partnership was starting to fracture at the time of “Pepper,” and McCartney begins to dominate as he didn’t earlier. That’s true not only of his songwriting but also of his playing: on “Pepper” the bass is more prominent than before, consistently showcasing McCartney’s accomplished playing. And the album’s concept was McCartney’s idea: for the first time, Lennon is not leading (or co-leading, as he was on “Revolver” and maybe “Rubber Soul”), but following.

From comments Lennon made in interviews over the years, it’s clear that the lavish praise the album received got under his skin. Post-“Pepper’s,” Lennon withdrew from his leadership role, and once that happened, the band was doomed (in my opinion). It was only a matter of time before Lennon decided he wanted out.

It’s hard to hold a group of talented, willful people together over the long haul and have them all working towards the same goal. People change. Eras end. Destructive patterns repeat. Recriminations and regrets fester. Just a few years after the triumph of “Pepper’s,” the Beatles broke up. That they managed to create “Magical Mystery Tour,” “The Beatles,” “Let It Be,” and “Abbey Road” in their remaining years is something of a miracle. The acrimonious, protracted end of the Beatles is something I don’t think any of the members ever fully recovered from.

At the end of “Mad Men,” season five, things look as superficially bright for the agency as they looked for the Beatles in the afterglow of “Sgt. Pepper’s.” The attention and money is rolling in, and it seems like a good time to expand (take on an additional floor of office space, if you’re CSDP; start Apple, if you’re the Beatles). But it’s a good bet that that expansion is the beginning of the end. Because nothing tests a group’s structural soundness like success.

This is great, thanks for taking the time to put this together, Nancy. Looks like we are the only ones interested in this topic, however. Oh well, I still find it fascinating. While I dont believe Weiner styled this season directly to compare with Pepper, there are many instances of him hinting subtly and not so subtly to Beatles/Pepper. I still can’t get over the fact that an entire episode revolved around ‘Tomorrow…’ One of the problems with Emily Vivianis theory is that it’s too damn long! If she wants people to read it she really needs to make it concise and to the point. Hopefully on Season 6 of Mad Men there will be a scene of the main players making a pitch to clients up on the rooftop.

Craig, to me the bigger question is the more interesting one: what happens after you get everything you thought you wanted? Don Draper’s definitely wrestling with that at the end of season 5, and the Beatles wrestled with it from the mid-60s until the breakup.

Not many people have come up with a wholly satisfying answer to that question.

Great point. I believe Don directly references this age-old problem in the penultimate episode of this season.

During the aggressive pitch meeting with Dow Chemical when Don is attempting to explain why Dow should take on SCDP as a client he says:

“Even though success is a reality, it’s effects are temporary.” And, “What is happiness? It’s a moment before you need more happiness.”

It’s a question I won’t even attempt to answer, as the answer will be different for everyone, if there even is an answer. What did the Beatles do? Well, I don’t have to explain to this group what they did. But it seemed they were definitely searching for that answer with their foray into India.

Ultimately, it is impossible to find ultimate, blissful happiness at all times. If that were to somehow occurr, one would have no idea that they were even happy, having never experienced sadness.

I may be veering off the tracks a bit here. Thanks for chatting, Nancy.

I concur with Nancy that the Pepper themes are universal and so can be applied with some validity to Mad Men. For that matter, they can be applied to a vast preponderance of (at least Western) fictions, whether written or dramatized, in the modern age.

I’m all in favor of fans devising personal meanings and finding obscure significances in Beatle music, or any other art that they are passionate about. I’m a fan, and I do it all the time. But not all meanings are interesting, and not all significance is resonant. Mike has the term “fan-wankery”; quoting the famous Beatle fake “The Candle Burns,” I once referred to fans “building molecules with garden hoes.” Walter Matthau, playing Sen. Russell Long in JFK, said “those Warren Commission boys were picking natshit out of pepper.” There are many fitting names for the practice of isolating small connections, some plausible and others no-fucking-way, to make a new interpretation of a familiar artwork–rewrite its story, essentially–and that’s what this Viviani theory is up to.

I like that Viviani is modest and affable about her reaches for meaning, and that she doesn’t order us to believe her theories, only asks that we “entertain” them. She loves the Beatles, and she loves Mad Men. Nothing could be more natural for a certain kind of imaginative fan than to want to forge a connection between the two, and convince yourself it exists in objective reality.

But having entertained, I conclude that to make such an act of imaginative assertion as this meaningful to me, there must be stakes involved; and here there are simply none. At the least, the works thus connected must benefit, be enlarged somehow, by having been connected. In this case, neither the album nor the show is illuminated or made more interesting for me. In fact, the show is minimized because the sources that feed it are reduced to something quite small, calculated, and un-universal: Mad Men = Pepper. QED. When all along, I have been compelled by the show because I thought it was after MUCH bigger game.

To make like a broken record, I detest the intentional fallacy, which insists that interpretation of art be limited to whatever we know (or imagine) the creator’s intentions to be. While we can be certain, I think, that Weiner et al did not consciously model their show on Pepper, I care about that only a little: the meaning of art should never be restricted to the meaning preapproved by the artist him/herself. (For one thing, if the art only has one level of meaning–the one consciously calculated by the artist–it is not art but a species of propaganda.) But if you want to make personal meaning out of art and have it mean anything to me, it must be tethered to larger weight, a bigger view with implications beyond the hunting of encoded messages to create a glorified acrostic or sodoku.

Nancy’s comment, what she calls “the bigger question,” is of course far more germane. It is universal, it is interesting, it clearly applies to both Don Draper and JPG&R, and it is undependent on the forcing of connections that not only are painfully tenuous but diminish the works we mean to extol.

Ok. So you agree with Nancy, again. What could possibly be the bigger view with greater implications? Its a tv show, its not going to teach us some groundbreaking knowledge about human nature. It was a cool theory that Viviani defended quite well and enthusiastically. Thought provoking and potentially meaningful to the series, her theory can add to the enjoyment one receives from thinking about the show, even if one ultimately rejects her assertions. It certainly does not diminish either the show or the album. Far from it; in attempting to connect this show with perhaps the most lauded album of all time, she is only extolling the fact that this show is similarly lauded if not quite as historically significant.

OK, next you’ll tell me that there’s no connection between “Wizard of Oz” and Dark Side of the Moon! 🙂

Devin wrote:

(For one thing, if the art only has one level of meaning–the one consciously calculated by the artist–it is not art but a species of propaganda.)

Or, to use another term: advertising. 🙂

It is natural, inevitable, and automatic for audience members to assign their own meaning to creative work. This is the strong force; the weak force is the creator’s intent. So Devin, there’s no need to despise the intentional fallacy–it evaporates almost immediately of its own accord, and never faster than in work that is truly “popular.” As I’ve told you, I’ve spent the last ten years telling people that, “No, Barry Trotter does not smoke pot in the first book. I didn’t write that. You added that.”

It’s impossible, too, to talk about this issue without bringing up the role of the academy, which has in the last 50 years accepted the use of pop culture as “text.” I have no beef with this–I like it, in fact, and think to do anything else would be snobbish and counterproductive. But this, too, weighs against authorial intent–so much so that when I was a wee lad at Yale, the lit-critters I knew claimed that authorial intent was immaterial. As a writer then I resented that; as a writer now, I resent it even more. On the one hand, you’ve got corporate “partners” trying to take financial control, and on the other, critics insisting that they have equal interpretative control, and the meaning of the work being determined by a kind of psychological crowdsourcing. Which is itself prone to they effects of marketing. To use my earlier example: my publisher marketed my book as schlock for commercial reasons, which makes parents think Barry’s a pot-smoker, but I’M the one that gets the angry parent emails.

Fans embroidering upon–or even replacing wholesale–authorial intent is a a mark of success. It means people find the work meaningful. But all creative work comes, at least in part, from an author’s drive to communicate; and the rigor of creation usually makes that communication specific, rather than general. That specificity is worth noting; it matters. Authors cannot FORCE audience to think certain things, or interact/interpret in certain ways; but stripping authorial intent from a work of art turns it into a pure commodity, with the only unquestioned authority left being commercial control. Bad, bad, bad for creatives.

The middle way–acknowledging authorial intent, but not being limited by it–is best, IMHO.

Mike, the reason I detest the intentional fallacy is that it is the favored club of know-nothing internetters to attack writers who try to do something creative with work which they (the internetters) already have set ideas about. Can’t recall how many times I’ve read Amazon reviews or blog rants by people who have already decided what (for instance) the Basement Tapes are all about and how dare Greil Marcus suggest they mean something else without direct Dylan quotes to back it up. The I.F. only evaporates if you don’t take it for granted in the first place, which a lot of people do, more out of the academy these days than in it.

The middle way–acknowledging authorial intent, but not being limited by it–is best, IMHO. Couldn’t have said it better. Wish everyone agreed!

“What could possibly be the bigger view with greater implications? Its a tv show, its not going to teach us some groundbreaking knowledge about human nature.” It’s not my job to say what the implications of theory should be, it’s the job of the theorist to provide them (or not). And change “tv show” to “popular music,” and you have what a lot of people, including fans, say about pop music, such as the Beatles. Just enjoy it, don’t think about it. It’s fun. No meaning. (The intentional fallacy strikes again.) Would you apply your sentence to the Beatles? It’s just pop music, after all.

The point is not “groundbreaking knowledge about human nature.” That’s a straw construct and nothing to do with what I wrote. The point is what art has always attempted to provide: fresh poetry, insight into character, new riffs on the themes and stories that have haunted our race–all of which Mad Men has been particularly sharp and consistent in providing.

Craig, you solicited response, and here it is. Clearly, I don’t have to credit a theory with being cool if I don’t think it’s cool. Nor is enthusiasm a substitute for any number of other things–cogency, and yes, a “greater implication.”

The I.F. only evaporates if you don’t take it for granted in the first place, which a lot of people do, more out of the academy these days than in it.

That’s really interesting, Devin. I’m going to have to think about it more; it seems right–the internet is surely a overliteral, hammer-the-nail-down community.

The other thing I think is important is to keep one’s love front-and-center. Two people who LOVE The Basement Tapes, or Mad Men, or The Beatles, have a powerful source of sympathy, and that’s not to be discarded in this world…especially over differing interpretations, which necessarily are as individual as fingerprints.

Mike, sensitivity to the trolls is exactly why I glommed onto this glancing insight from Starostin, the web critic recently spotlit by Nancy:

“The rather obvious trend, as my experience has shown me, is that people usually value musical criticism not so much according to the literary skills or erudition of the writer, but according to how much their opinions on music coincide with those of the writer.”

Damn straight. I think it has a lot to do with the younger, more entitled generations that so many are unwilling to take a work on its own terms, rather than assuming the work must conform to whatever terms they brought to it.

Point taken about sympathy … though you know better than most of us how thorny can be a shared love. Haven’t you taken some hits from Harry Potterites in your time, just as I’ve been roasted by my share of Beatlenuts?

I’m really interested in the question of how much weight to give authorial intent when interpreting a work. I agree that it’s crazy to discount apparent (or stated) intent, but it’s also clear that great/successful works go beyond that intent. And artists vary greatly in how directly they divulge intent.

To take a Beatle-related example, I think McCartney is not very analytical about the meaning of his songs. I don’t mean that he has no intent, or that he never says anything interesting or pertinent about what his songs mean, but that I often come away from reading interviews with him thinking that he’s either dodging the question of what something means or that he just doesn’t think that way. (Or that he doesn’t like thinking that way.) That’s in contrast to Lennon, who does strike me as pretty consistently analytical about the meaning of his songs.

Same thing is true in literature. You have Dickens saying that everything of purpose he wants to say about his fiction is in the story itself, and you have Tolstoy writing two epilogues about the meaning of “War and Peace” after the plot concludes, because he can’t let go of telling the reader what the book means.

So as interpreters I think we need to take that middle way and attend to the particular author/maker and his/her way of proceeding. We also have to recognize that any worthwhile work of art exceeds our ability to restate it. If it could be captured in a restatement, it wouldn’t be art (credit to Cleanth Brooks).

Beyond the “what happens after you get everything you thought you wanted?” question, I’m interested in the way “Mad Men” is dealing with the fate of a working group over time, and the way such a group tends to fracture under stress. I think that’s part of the dark undercurrent of “Pepper” — the Beatles’ sense that things were going to fall apart. I at least don’t hear it as a happy flower-power LP.