- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

No Sgt Pepper? Did they put stupid in the water of Williamsburg?

Okay, today I had the kind of experience the internet is made for. I was sitting in my doctor’s office reading Entertainment Weekly and—look, I know that if I’m reading EW, I get what I deserve. I suppose I am showing my age, expecting a magazine to be not-idiotic because it’s on paper, but still: there I was reading EW’s list of the Top 100 LPs of All Time and Revolver is #1, and White is #12, and Abbey Road is #22 and Rubber Soul is #65 or something, and…

Sgt. Pepper isn’t even listed. Are you trolling me, EW?

Now I realize I ride a couple of hobby horses pretty hard on this blog. Recently a commenter called me out on that, and he/she isn’t entirely wrong. But folks—in a world where Sgt. Pepper isn’t even listed in the Top 100 LPs of All Time, you gotta speak up.

I know a bit about compiling lists—see here for my essential comedy bookshelf—and every such list is flawed, and personal, and designed to spur discussion. But there’s something woefully wrong with your brain if you like Revolver enough to put it at #1, and not even list the follow-up which, in addition to being an extension of Revolver in some important ways, and hugely innovative in its recording technology, packaging, and conception, at the time (as I have endlessly pointed out) was considered to be the absolute epitome of artistry in not just rock, but one of the high points of popular culture of the last 100 years. Were all those people that wrong? Were all the lists that commonly placed Pepper at or near the top that wrong? Or are the EW compilers playing some kind bullshit rock-snob game that shows just how infantile and, yeah, immature rock music is as an art form?

In addition to currency bias, in the world of pop culture criticism there’s a premium put on a kind of emotional hardness—what a 14-year-old boy thinks serious artists act like. It’s very male, and very adolescent. In this worldview, Pepper (and the brief psychedelic movement for which it stands/stood) is definitely uncool. For the very same reasons, and to the same degree that Paul McCartney, the supposedly simple/happy/emotive/romantic/merely-entertaining Beatle, is uncool. Guys, just say Paul has girl-cooties and be done with it.

If somebody likes The Beatles, but doesn’t like Pepper, I think that’s fine; a bit idiosyncratic, but whatever. Ditto if a person likes The Beatles, but doesn’t like McCartney—you run into those people, bundle of contradictions though they may be. But if you’re a critic (or better yet a board of critics), you have a responsibility to be aware of your biases, and account for them, and have a little humility in the face of previous critical opinion. And not be a bunch of idiots.

|

| “Pardon my girl-cooties!” “I don’t care!” |

Sgt Pepper is regularly downgraded precisely because it—like The Beatles themselves—puts the lie to the idea that current pop culture is the best it’s ever been. This myth of progress is at the very heart of EW, and everything like it. Pepper organically achieved what forty years of ever-better marketing hasn’t been able to replacate. And in this world of pop culture, where what’s new and now must be better than what’s old and then or else the whole mechanism stops, that’s an unforgivable sin. Pepper bruises the modern ego because nothing—not Nevermind, not Never Mind the Bollocks, or anything else—has ever come close to what it achieved.

Here’s Jim Dickson, mentor of The Byrds:

“It was totally awesome. Sgt Pepper was so far beyond anything we could imagine producing or doing that it overwhelmed us. It was like Miles Davis with Sketches of Spain. He just left everybody in jazz with no place to go…What was new in it? Well, all that George Martin production, a backdrop of British music-hall and the tremendous construction, the continuity of songs, the braveness of the music. You could be frightened to death and hear that album and feel OK. It was magnificent. Overwhelming power.”

Or activist Keith Lampe, who recalled listening to it with Abbie Hoffman:

“When ‘Day in the Life’ ended there was silence for a long, long time. It increased our confidence in the future a great deal. It was as though the millennium was at hand, and so the music was necessary to us as activists. It was something that allowed us to keep building momentum rather than exhausting oursevles in repetitive exercises. And I still think of it as a tremendous cultural importance, and its effects are still to be seen here and there today.”

Or the writer Langdon Winner:

“At the time Sgt Pepper was released I happened to be driving across country on Interstate 80. In each city where I stopped for gas or food—Laramie, Ogallala, Moline, South Bend—the melodies wafted in from some far-off transistor radio or portable hi-fi. It was the most amazing thing I’ve ever heard. For a brief moment, the irreparably fragmented consciousness of the West was unified, at least in the minds of the young.”

But let’s end with Allen Ginsberg, who knew a thing or two about cultural landmarks:

“After the apocalypse of Hitler and the apocalypse of the Bomb, there was [in Sgt Pepper] an exclamation of joy and what it is to be alive…They showed an awareness that we make up our own fate, and they have decided to make it a cheerful fate…Remember this was in the midst of the Sixties, it was when some of the wilder and crazier radicals were saying “Kill the pigs.” They were saying the opposite about old Sgt Pepper. In fact The Beatles were dressing up in uniforms, but associating themselves with good oldtime vaudeville authority rather than sneaky CIA, KGB, MI5 or whatever. It was actually a cheerful look round the world…for the first time, I would say, on a mass scale.”

And that cheerfulness, ladies and gentlemen, is what real revolution—real rebellion—real change and real courage looks like. If you can’t see that, the problem isn’t with Pepper, it’s with your own head.

Yep. It was a ridiculous omission on a stupid list. Equally irritating was EW putting Plastic Ono Band at No. 40, ahead of Rubber Soul, and omitting Ram and All Things Must Pass. I’m perfectly willing to accept that none of the Beatles solo albums belong on a list of the 100 greatest albums ever. But Plastic Ono Band is more bullshit Lennon hagiography. It is NOT a better album than Ram or All Things Must Pass and all 3 albums have been influential in their way.

I totally agree that Sgt. Pepper has been downgraded in the view of male music critics because it’s viewed increasingly as a McCartney/Martin creation, rather than as a band project. But then again, Paul’s leadership is all over Revolver, Rubber Soul, Abbey Road and the White Album, too.

Then again I get equally irritated lately at how many Web sites are doing these funky lists the purpose of which seems to be to attack John Lennon as a “wife beating asshole.” There was the “10 Unpleasant Facts about John Lennon” on Listverse.com. And Cracked.com just published “5 Beloved Celebrities Who Were Nothing like You Think” and described Lennon as “an abusive asshole who hit women.” Of course Cracked also has a music writer who regularly takes potshots at Paul’s solo albums.

Amazing that both men continue to be such big targets after 50 years — used by Web sites that write provocative things just to get us all to “click.”

Sgt. Pepper is a brilliant album. It should have been on that stupid list.

— Drew

Amen, Michael.

God knows I gallop on my own hobby horses here, but not even listing “Pepper” in the top 100 albums is indisputably insane.

Reminds me of the way Shakespeare gets downgraded in some graduate departments of English, and I think the reason is similar: a desire to knock a cultural icon off its pedestal, thereby proving one’s own daring and cleverness. It may be fair to say that “Pepper” has received too many accolades over the years and other worthy works too few, as it may be fair to say that there’s been too much Shakespeare-worship, and too little attention to playwrights like, say, Christopher Marlowe. But to claim that Marlowe’s body of work surpasses Shakespeare’s is nuts.

I’d be interested to know what DID make the rest of the list. (Not interested enough to buy the magazine, however.)

In the end, I think “Pepper”‘s quality ensures its staying power. Quality will endure and resurface, despite the best efforts of trendy criticism. There’s a reason our local community is staging “Shakespeare in the Park” and not “Marlowe in the Park.” [No offense, Mr. Marlowe.]

You can read the whole list here:

http://www.mstarz.com/articles/15514/20130701/entertainment-weekly-top-100-albums-of-all-time-list-see-magazines-strange-awesome-picks.htm

“Purple Rain” is #2???? I like Prince a lot, but really?

The problem, I think, is that “greatests” lists are not purely about quality, nor even about what most people actually happen to love. When you’re doing a list of “greatests” for a widely read publication, you can’t just get a bunch of people in a room and vote on what everyone’s favorite things genuinely are. Rather, you have to balance what you truly love with what has had a formative, lasting cultural impact, whether you happen to love it or not. This may seem dishonest or corrupt, or the entertainment industry stroking itself. But I would argue that that’s the only way to make a meaningful “greatest” list, because what people actually happen to love and feel attachment to is highly personal and eccentric. You’d never get consensus if list-compilers just voted their tastes. (Heck, I would have included Phoebe Snow’s first album, in my view the most underrated album in recorded-music history, but, alas, almost no formative or lasting cultural impact.) I suspect the writers of this particular list were trying to shake things up by excluding Pepper and including Nevermind and Purple Rain: they’re making a statement that the world has moved on from the baby-boomer generation. In a way, it can be viewed as a valid decision, because by now most popular music owes much more to Purple Rain and Nevermind than to Pepper. That’s not to say that they’re better than Pepper: they are not. But they are more indicative of what tastes have evolved into now, than Pepper is. Pepper indicated a direction of high ambition, grand statements, orchestration, social consciousness. As long as popular music actually followed that direction, Pepper could be seen as one of the greatest albums of all-time. Popular music today, however, has gone in a direction of lewdness for its own sake; ugly, grating sounds; sarcasm rather than gravitas; aggression rather than joy. And it makes sense to see Purple Rain and Nevermind as among the most important formative steps in that process. (And, for that same reason, it makes sense to retain Revolver and the White Album on the list.)

I wonder if younger generations are less and less impressed with Pepper because they’ve heard countless, weaker imitations. The people who heard it in 1967 were astounded by it. I remember hearing it for the first time in 1967 as a nine year old, and I actually thought there was something wrong with either the record player or the record itself when I got to the end of Day In The Life. The whole thing sounded like it could have been recorded on Mars, for all I knew (I hadn’t yet heard Revolver). Like going from grayscale to technicolor.

The old cliche, “you had to be there” might apply to someone younger, who has heard five decades worth of pop pastiches, then turns to Pepper and wonders what all the fuss is about.

And on the subject of written comedy, I’d have to add “My Ten Years In A Quandary (And How They Grew)” as well as “The Early Worm” by Benchley. I discovered the Benchley Roundup in my middle school library (some kind soul had stocked it with Thurber, E.B. White, and the two Benchley anthologies). I proceeded to my local library that contained every Robert Benchley book, from “Love Conquers All” (first editions) all the way to “After 1903, What?” Needless to say, I was hooked, and remain hooked.

Is there a way to allow jaded young people who compile lists of great albums while leaving out Sgt. Pepper … is there a way to allow them to hear it as if this were 1967?

– hologram sam

These lists always make me mad, and they have no bearing on any sort of reality whatsoever. They are just easy to compile and they fill up print space. Why not write about music in a more meaningful way? I really love the macho “Greatest Guitarists Ever” type lists that RS puts out now and then. Apart from Jimi and Eric, the really great players are all at the bottom! Richard Thompson is #83 while Slash is #4. It is silly. The Beatles made so many great LPs, that they all deserve to be in the top 100. I guarantee that With the Beatles wasn’t in there… or Help, or A Hard Days Night.

Guys, just say Paul has girl-cooties and be done with it.

LOL. Perfect.

So many good comments. Thanks, peeps.

@Drew, don’t pay any attention to Cracked.com. It’s a humor site and in our overheated contemporary culture, the only way to get someone’s attention is to be outrageous–to “color outside the lines” on purpose. Done it myself; made a conscious choice NOT to do it anymore; and have paid quite a price. But don’t worry, I suspect no real opinions are being formed from Cracked, only callow, shallow zeitgeist-surfing.

@Nancy: I love me some Prince, but even we Prince fans generally agree that “Sign O’ The Times” is his major artistic statement–as wonderful as “Purple Rain” is–and so this is just EW being bloody-minded. Or young. Or dumb. Or all three. I do think this list is a conscious effort to assert independence from the Baby Boom generation, but that is foolish. It’s like purposely not mentioning Giotto, Raphael, Leonardo and Michelangelo because you want to assert figurative religious painting’s independence from the Renaissance. Generational identity is a false construct created by marketing/advertising, not reality. If you aren’t smart enough to tell the difference between marketing and reality, you shouldn’t be critiquing pop culture.

@Mudarra: “you have to balance what you truly love with what has had a formative, lasting cultural impact, whether you happen to love it or not”

^^^EXACTLY. And what chafes my biscuits is that none of these people have any feel for history. Most pop culture critics don’t–they understand history on an “American Experience” level of depth if at all–and rock critics are especially dimwitted in this regard. The vague resentment that anything happened before you were born is one of the most crippling aspects of modern culture. Our current era of wide public health, good nutrition, education and ability to travel should be fueling a Renaissance; and it’s more precarious than we think. Instead we fritter it away, distracting ourselves with “lewdness for its own sake; ugly, grating sounds; sarcasm rather than gravitas; aggression rather than joy.”

@Sam: “is there a way to allow them to hear it as if this were 1967?”

Perhaps if people were taught history on a deep level–were encouraged to FEEL it, as one must to understand–it could happen. But not as long as the Sixties are reduced to a couple of grainy clips of women dancing topless in Golden Gate Park.

@hologram sam

I first heard Sgt. Pepper in the spring/summer of 1991, when I was 14 years old. And I DID think it was pretty amazing. I listened to it over and over.

Here’s the thing though – I also listened to Highway 61 Revisited for the first time that same spring/summer, and played it over and over as well. And then, of course, I moved on to other albums like Blood on the Tracks when it came to Dylan; and the entier Beatles Discography, focusing in on albums like Abbey Road and Rubber Soul.

So what I’m trying to say is yeah, it might actually be a case of “you had to be there” when it comes to Sgt. Pepper these days. I mean, I was there – that same year, 1991 – when Nirvana’s Nevermind first came out. I remember how, one minute it seem to be nothing but hair bands on MTV, and then the next minute it was nothing but grunge/alternative bands and the whole rock music scene seem to flip on it’s head and be upended. But unless you were there, it’s probably hard to fully get how much that album changed things – how different it was from the majority of what was going on at the time when it came to rock music.

I remember hearing from my dad what it was like when Sgt. Pepper came out, and I got/get the historic significance of the album. (So I agree, it really should be somewhere on the list). But if you weren’t there then, while you might – in an abstract way – get the historic significance of the album, it might be hard to not think that the album might be overrated in the praise it receives. Because, IMO, it IS such a time-capsule of that time – 1967-68 – and psychedelia.

Whereas you hear something like Abbey Road, or Revolver, and a lot of the tracks on them sounds like stuff that could have been made just last year.

-MGAnon

@MGAnon, that’s a great comment.

Speaking as someone else who was there in 1991–I was 22–and saw how Nevermind totally changed the scene, I want to explain what the difference is, to me. This will likely explain why I hold Pepper (and Revolver,and MMT) in such high regard.

The change you describe from hair metal to grunge was wholly a change in fashion. Hair metal had been what MTV played, then grunge became what they played. To be followed by Britpop or Electronica or whathaveyou.

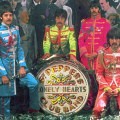

The thing that must be understood about Pepper–and about psychedelia in general–is that it was the culmination of cultural trends that had been growing since at least 1945. And it wasn’t restricted to music. Pepper was the crowning achievement of a whole type of culture, an underground created by a bunch of different writers and artists, accelerated by hallucinogens. Pepper mixed a huge number of disparate elements, and was an accessible way into them–that’s why the cover is so appropriate, and why things like Paul’s granny music makes sense on The Beatles’ three psychedelic LPs.

Grunge is a fashion trend, which is fine. Psychedelia was an attempt at a whole new cosmology and way of living; it had its intellectuals like Alan Watts and Tim Leary; its mystics like Ram Dass and Maharishi and a zillion other people large and small; it was a total change in values. Grunge was a temporary variation in musical tastes which was awesome, but it wasn’t any bigger than, say, what came out of Manchester in the early to mid-80s.

Psychedelia was a whole way of life, and it’s a way of life that has existed ever since. If you go to a Farmer’s Market (or even Whole Foods), you’re feeling its effect; if you’ve ever meditated or done biofeedback, or smoked pot or read an alternative weekly, or done improv or a poetry slam, or participated in a sit-in…

At the time, people really felt that this new way of being was powerful enough to change the world entirely. And it did, to some degree. But one of the things that happened along the way–beginning in 1968–was a cunning co-optation of the counterculture, so that it became impossible to determine what was an authentic expression of a new set of values, what was marketing, and what was simply a new kind of guitar sound. So people my age and younger, who have necessarily developed a kind of cynicism towards this stuff, can be forgiven if they don’t recognize the difference between the real thing (the flowering of a worldwide youth driven counterculture between 1964-67) and something The Gap sells for $24.95 a pair. But there WAS a difference and there IS a difference, and it’s important that people learn how to perceive it, especially if they are artists themselves.

@Michael Gerber

I think you’re spot-on when it comes to counter-culture being co-opted and then marketed. Being someone who was born after – almost 10 years after – the whole psychedelia scene of the late-60s, I couldn’t even begin to tell you what was “real” and what just a “co-op” of it. Not with any sort-of authority anyway.

In defense of Grunge however I will say, I don’t think it was just a fashion trend. At least, not at the start. All Grunge really was was punk rock, which just kinda went underground during the 80s, during the age of hair and glam rock/metal. I was just a little kid during the 80s, so I wasn’t deep into it, but even I could see there was a formula being put to that type of music. Occasionally you’d have groups that would go against the grain here and there – you know, like Guns N Roses – but for the most part there was a formula being followed.

I think when Grunge first broke out, meaning when Nirvana first broke out, it all did so because it was just so different from the formula of rock/metal that had been going on for a least a decade. People were tired of it, and wanted something different. What happened, however, was the co-opting of Grunge into a fashion statement and trend happened almost instantaneously when it did so.

Grunge could never be a way of life the way you describe psychedelia being, because it was a life that many felt they were living already, and desperately wanted to get out of. The roots of it were that of feeling alienated. So marketing it as a fashion trend or anything else, something that you should try to be, was actually a counter to the whole advent – the whole reason – behind the things people like Kurt Cobain was singing about.

Is it any wonder it all got to him in the end?

–MGAnon

MGAnon: I mean, I was there – that same year, 1991 – when Nirvana’s Nevermind first came out. I remember how, one minute it seem to be nothing but hair bands on MTV, and then the next minute it was nothing but grunge/alternative bands and the whole rock music scene seem to flip on it’s head and be upended. But unless you were there, it’s probably hard to fully get how much that album changed things – how different it was from the majority of what was going on at the time when it came to rock music.

Exactly the point I was trying to make, you said it more clearly. A young person listening to Nevermind today would have heard so many mediocre Nirvana imitators that the original would lose impact.

Play Buddy Holly’s “Words Of Love” to the list makers at EW, and they won’t hear anything special, it’ll sound like Herman’s Hermits to them, or maybe the Archies. They won’t comprehend how completely revolutionary Buddy’s recording was in 1957, how it pointed to a thousands of british invasion bands that wouldn’t appear for another decade.

– hologram sam

@Mudarra: “you have to balance what you truly love with what has had a formative, lasting cultural impact, whether you happen to love it or not”

Like Mike, I find this to be the crux of the gist. But that the cultural impact and historical importance of a work like Pepper is undeniable under objective criteria also means that compilers exercising historical perspective and aesthetic conscience will tend to come up with very homogeneous lists. 50% or more will be agreed-upon landmarks for which one may or may not feel great enthusiasm, with the other half taken by eccentric passions that will inspire rancor precisely for their arguability.

There’s no way for such a list to be interesting without upsetting people, no way for it to be judicious and scrupulous without also being dull. The only reasonable solution is to declare a moratorium on all such lists in the public prints. Those who would compile them (I have a bunch myself) should not publish them but should reserve them for the barstool, patio, and other spots where friendly and irresolvable feuds are hatched.

there’s a premium put on a kind of emotional hardness—what a 14-year-old boy thinks serious artists act like.

Excepting, of course, the type of 14-year-old boy who is writing a dreamy swing song about the pleasures of old-age and grandparenthood. 🙂

But seriously, @Michael Gerber, your whole post just brings me back to one of my unanswerable questions – what the hell is wrong with rock critics? They are, as you say, obsessed with whatever they thought the music was about when they were fourteen – usually some version of “how to be cool” with a particular focus on NOT being whatever they most feared in themselves (often, “weak”). It seems impossible to find anything to read about a piece of rock music that has anything to do with the actual music and lyrics, let alone the larger cultural impact viewed from any lens wider than the author’s own struggles with his parents. Often they don’t even talk about what personally moved them emotionally, because that’s not their game either – all they want to do is define what’s “cool” in such a way that they are on the right side of it along with whatever musician they’ve chosen as their avatar. /rant

Excepting, of course, the type of 14-year-old boy who is writing a dreamy swing song about the pleasures of old-age and grandparenthood. 🙂

And isn’t that WONDERFUL? That’s totally the kind of 14-year-old boy I like; and I like John Lennon at the same age, when he’s being thoughtful and creative and positive, when he’s writing and drawing The Daily Howl.

Absolutely! The stories of both of them as young dreamers are beyond adorable.

I’m enjoying this discussion tremendously. Devin: I quite agree about the inherent problem with “greatest” lists. To the discussion of grunge, I’d like to add that I always saw grunge as a rebuke to the 80’s – the music, the clothing, the whole visual aesthetic, the Reagan-defined conservatism. In a way, grunge has had a lasting impact in that there hasn’t been another supposedly such slaphappy, complacent time since then. Even in the economically prosperous 90’s, the culture was still dominated by cynicism and detachment, and when the economy turns up again I bet it will continue to be. Isn’t this partly a legacy of grunge?

To the praise of Pepper, I’d like to add the fact that the album itself has tremendous historical and cultural consciousness *within* it. One small example: whenever I hear the transition from “Within You Without You” to “When I’m 64” – a transition so stark, and yet so perfect – I always think of the British Empire…

@Mudarra–

I think it’s a fundamental misreading of the 80s to call them slaphappy or complacent. That was only true about the MEDIA produced in the 80s.

The early 80s were dreadful, economically–the separation of the 1% from the rest of us suckers began the moment Reagan took office and we all felt it. Psychedelia would not have happened without the incredible middle-class prosperity after 1945, and was based on a democratization of education unheard of in the history of the West. In the US, it was the GI Bill followed by all the Boomers going to college (and graduating without meaningful debt). In the UK, class distinctions were being shattered and middle and lower-class kids were going to art school and even Oxbridge. The hoarding of privilege which began with Reagan and Thatcher has been guided, to some degree, by an instinct to throttle any contemporary counterculture. Even if Wall Street began to boom after 1984, that was the kind of restricted prosperity that we’ve seen ever since. (Exactly the kind that encourages young rage, but doesn’t give it any room for anything more than that.)

Politically, the early and mid-80s were the worst years of the Cold War since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Every kid of my generation assumed that they were die in a nuclear war; there were massive protests all over Europe. Very paranoid, very hopeless. Things like “The Cosby Show” and Ratt were the media providing relief, but they weren’t an accurate or thorough reflection of that time, any more than “My Mother the Car” or Pat Boone was.

And that, to me, demonstrates the difference between grunge (and its forebear punk) and the 60s counterculture. Grunge and punk were primarily media phenomena, not political ones. Not that people in the grunge or punk scenes weren’t also political, but

1) both punk and grunge (like disco and hair metal and mope-rock, and etc) embraced nihilism, political apathy or disaffection to some greater or lesser degree. Punk fans will disagree with me on this, but I don’t see the Pistols as a political phenomenon, or an economic one–they were a media phenomenon created by political and economic forces. My guess is that this was very much accelerated by the post-psychedelic New Left idea of “the personal is the political,” wherein piercing your cheek with a safety pin was considered equivalent to political action.

2) Alienation isn’t enough. Yes, the punks hated Thatcher, but what did they recommend? Hippies not only hated LBJ (and Nixon), they were constantly experimenting with new economic models (the Diggers), and/or models of living (city communes, back-to-nature, etc). This is why I included Ginsberg’s quote about cheerfulness; that’s so important, and neither punk nor grunge had it.

I lived in Seattle in the aftermath of grunge (1995) and I can tell you that it was a hell of an interesting place, creatively. LOTS of great art being created, LOTS of fascinating people living off the fat of the society. But it wasn’t political, or politically powerful, in the least. It wasn’t perceived that way at the time, and isn’t perceived that way now.

(Same as before, with typos fixed)

There have been so many comments already that this one might not be read, but here goes:

I agree that Sgt Pepper belongs in the top 100. Its exclusion is either ignorance or Slate-esque contrarianism.

But I want to take issue with the contention that Sgt Pepper is joyful, or has a joyful meaning. Some of the music is upbeat, but overall the subtext (and sometimes the text) is very despondent. What does the double crescendo and crash in A Day In The Life mean? I am not sure i can put it Into words, but it’s not life affirming. If I am really paying attention when I listen to that song, the effect is devastating, and nowhere near joyful. The closest thing to a positive message the record has, I think, is that it’s ok to feel apart from everyone else – I’ve got nothing to say, but it’s O.K.

To be as brief as possible: with the exception of Kite, the songs are all about alienation/escapism/loneliness. Lonely is in the title. The meaning is hiding in plain sight. I could analyze the record song by song to prove the point, but so could any listener. It’s a trend that started with Eleanor Rigby, if not earlier – really examining loneliness.

The form of the album is exuberant, but its content reflects the fact that after Beatlemania, these guys were emotionally exhausted, cut-off, and in George’s case, displeased with ordinary life in Western society.

@SCBrain overall the subtext (and sometimes the text) is very despondent. What does the double crescendo and crash in A Day In The Life mean?

Yes absolutely SCBrain. To me every song on Pepper seems to project a feeling not of joy, but alienation. It always mystified me that a song like When I’m 64 could be construed as some type of joyous tribute to old age. I hear it as the opposite of that. To me the lyrics sound sarcastic especially the line “Yours sincerely wasting away” and “doing the garden digging the weeds-who could ask for more”. Even the super uptempo arrangement seems a bit sarcastic to me….almost a parody of itself. Likewise I agree that with the exception of Kite (because it doesn’t seem to mean much of anything)that all of the songs on Pepper are about loneliness and disaffection. I’m pretty sure it was Tim Riley in his book Tell Me Why, who also said this about Pepper and the songs on Revolver too. I don’t like Riley’s book but I do agree with his assessments of Rubber Soul, Revolver, and Pepper. They are the only critiques in his book that don’t come off as arrogant and biased toward Lennon.

but its content reflects the fact that after Beatlemania, these guys were emotionally exhausted, cut-off,

I agree completely and the music mirrored that. Maybe I’m crazy or perhaps reading too much into things, but to me the Beatles never seemed like particularly happy people, even before fame. They seemed to be rather lonely disaffected types all along, or at least from their teen years on. IMO quite a bit of their music seems to evoke sadness and lonliness.

I dunno, @SC and @girl, that’s not the album I hear. Here are my feelings:

The intro is very uptempo;

“Little Help” is fundamentally positive;

“LSD” is neutral–observational;

“Getting Better” is almost pathologically positive;

“Hole” is neutral–as close as Paul ever gets to revealing his secretly depressed side, but the music is very bright;

“Kite” is positive;

“WYWY” is George being dour;

“64” is, to me, positive–remember that to a kid who grew up as poor as Paul, “Doing the garden, digging the weeds” was the epitome of middle-class contentment;

“Rita” is actually perky;

“Good Morning” is as positive as Lennon ever got, which is mutedly so;

“Reprise” is positive;

and “Day” is gloomy as hell, almost apocalyptic.

I think it was the fundamental positivity of the LP which grated on Lennon so much as it aged; remember that seriousness was the hallmark of Great Art, post-68. If all of Pepper had been half as gloomy as “A Day in the Life” was, I think he would’ve liked it more. In other words, he disliked it because it reflects Paul’s emotional state–outwardly chipper, inwardly depressed, but always willing to try.

But I am simply justifying what I hear, and to each his own. I think Revolver–with the exception of “Eleanor Rigby” and “For No One”–is even chirpier than Pepper. One of the reasons I seldom if ever listen to Rubber Soul is how its music strikes me as down. But all of this is just my opinion, nothing more, and it’s interesting to hear yours.

@Girl

Yes, yes – and think about this – the Beatles are smiling on the cover of precisely one of their albums: the first one.

@ Michael.

Ah, I was certain it would come to this! Ok, here goes.

SPLHCB: Not much content, aside from saying that the Beatles are a *Lonely Hearts’* Club Band. They could have chosen any word, been any kind of band – they chose to be a Lonely Hearts’ Club Band.

WALHFMF: “Do you need anybody? I need somebody to love. Could it be anybody? I want somebody to love.” Guy is lonely. He has no one to love or love him.

LitSwD: Although I buy the story about Julian’s painting, clearly the lyrics are about an LSD trip; read: escapism. Think about John tripping for days/weeks/months at a time. Sad.

GB: I used to be cruel to my woman/ I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loves. “It couldn’t get much worse!” Bright on the surface, sad underneath.

Hole: Bright on the surface, sad underneath.

Kite: Not much emotional content there. Lyrics taken from a poster.

WYWY: Despondent and alienated from the people around him, who do not understand the true nature of life.

64: I agree with Girl’s take. And it’s essentially a marriage proposal because the guy wants someone to feed him when he is old, not because he is in love.

LR: Guy falls in love because civil servant looks like a little like a military man.

GMGM : I maintain that this is a very bleak song. He has nothing to say; he is so at a loss for what to do that he walks aimlessly around his old school. “Going to work don’t want to go feeling low down”; “Everybody knows there’s nothing doing/ Everything is closed it’s like a ruin/ Everyone you see is half asleep/ And you’re on your own you’re in the street.” And so on. Alienated.

Reprise: Well, this is just a reprise, but they do sing “Sgt Pepper’s Lonely (X5)” He is lonely, very lonely, and he is them.

ADITL: Just about as alienated as a song can be. Listen to that first “Oh Boy.”

Oh boy.

@SCBrain, you’re cherry-picking lyrics and ignoring the music entirely–which is cool, if that’s how you hear the LP. I’m not trying to convince you, I’m just sorry it’s not more fun for you to listen to the album (I suspect this is how HD’s White-lovers feel about me!).

When The Beatles want to write a depressed song, you know it. “I’m So Tired”; “I’m a Loser”; even “Yesterday.” Or, on SPLHCB, “Day in the Life.” Unquestionably bleak lyrics, and downtempo music.

Does listening to the first 30 seconds of Sgt Pepper or its Reprise honestly make you depressed? How about “Getting Better”? Or “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”? Or the braying horns of “Good Morning”? Really? The epitome of “granny music,” “When I’m 64” makes you feel depressed, bleak, sad, or blue?

You feel how you feel, but to me the music on the album is much too rich and uptempo to be depressing; and the lyrics are either observation, renovation or renewal. “WYWY” is George lecturing, but it ends with a group laugh. “She’s Leaving Home” is depressing kitchen-sink realism at the beginning, but by the end she’s having fun.

“I used to be cruel to my woman

I beat her, and kept her apart from the things that she loved

Man I was mean

But I’m changing my scene

And I’m doing the best that I can”

That’s not depressing, to me. It’s somebody trying to turn over a new leaf.

“Lovely Rita” ends with the narrator failing to have sex with Rita, but he’s good-humored about it: “Where would I be without you? Give us a wink and make me think of you”

Add to this the packaging of the LP–warm and colorful, welcoming in the extreme, unlike, say, White–and I think you’ve got something that’s predominantly positive. To me, at least.

Ah yes, I left out She’s Leaving Home! That one definitely supports my case. What fun is she having? Meeting the man from the motor trade? Some fun. She’s headed for the same life she left.

I think Paul has a more positive take on alienation in this album – that’s his style – but he’s the one with the hole, he says things are getting better when they couldn’t get much worse – but it’s still a positive take on alienation.

The very name of the album and the only song repeated is an almost amazingly obvious tell, so obvious it might be ham-handed if not for the disguise of the bright colors on the cover and the woodwind sections.

But I think the real key is this: the emotional punch and valence of any work of art comes from the ending. Change the ending, a comedy becomes a tragedy, and vice versa. Romeo and Juliet reveal that they just pretended suicide and are actually alive, ready to buy a starter home in the suburbs of Verona: comedy.

And the ending of SPLHCB is devastating.

@SCBrain, you clearly feel strongly about this! Thanks for such a nice discussion.

That’s a great point about the ending of works of art. So do you believe that Revolver is entirely about the bleak, alienating void that Lennon was channeling via LSD and The Tibetan Book of the Dead? Or that the true nature of White, that sprawling masterpiece, is revealed in Lennon’s “Good Night”, sung by Ringo? Or are you saying that this is true only in the case of Sgt Pepper? And what do we do with the inner groove, then?

You’re using sequencing and lyrics alone, as if the LP was a book of poetry; I’d say the music matters as much if not more. And if you want to say it’s bright on the outside and dark on the inside, I’d agree with that 100%, with the brightness of the music and packaging tipping the scale in that direction. But fundamentally depressing or alienating, either as an expression or a listener experience…that seems to be rarely expressed. But if that’s how it hits you, that’s inarguable.

As to the title: A lonely hearts’ club is an attempt by lonely, isolated people to come together to find love. “Eleanor Rigby” needed a lonely hearts club! This, to me, is renovation, optimism in the face of challenge. Quintessentially McCartney, and absolute anathema to post-68 Lennon.

@Michael

Nice chat.

Re: endings of works of art: I don’t think all the Beatles’ albums cohere as works of art; especially early on, they are collections of songs, and the song is the unit of analysis. Rubber Soul is terrific, a great collection of songs (or a collection of great songs) but I don’t think that “Run for Your Life” presents any kind of summary statement.

The White Album doesn’t cohere as a work of art, either – its strength is its amazing breadth, as well as how inventive the songs are.

I think there are only two that cohere as works of art: Abbey Road and SPLHCB. (Abbey Road is basically a break-up/farewell album.)

I really liked your point about psychedelia as a political movement, in contrast with grunge or disco. I would contend that psychedelia, with SPLHCB as its most foremost explicit statement, was a *critical* political movement, pointing to the fundamental inadequacy of “straight” society and middle class bourgeois values.

I also like your formulation, bright on the outside and dark on the inside.

This discussion really does put into perspective, for me at least, how much a first impression of a song can make you think of it.

Because I didn’t first hear Sgt. Pepper until 1991, the first version of “With a Little Help From My Friends” that I ever heard was the Joe Cocker version – because it was used as the Wonder Years Theme, and then I saw him perform it in the film/documentary about Woodstock. And that song didn’t sound cheerful *at all* when I heard him sing it. And it wasn’t just because of the tempo change or anything like that. Joe’s version sounded quite dark in places to my listening ears. Especially when it came to the “Do you need anybody?” part(s).

So when I finally heard Ringo’s version on Sgt. Pepper, I was actually quite shocked/surprised by how happy and cheerful this original version of the song sounded. The lyrics were exactly the same, but it was the *style* in which they were delivered which made the difference in how it sounded to me when hearing the version on Sgt. Pepper vs the Joe Cocker version.

So I think Pepper is, more or less, a upbeat album; but I think that mostly has to do with they style the presented most of the songs (like WALHFMF) in.

–MGAnon

What’s that great Epstein quote about the Beatles having the prefect blend of happiness and sadness? I think its in the Compleat Beatles documentary. Personally, I love the sad/melancholy stuff. Music is so powerful- it can come straight from those lonely places that we never talk about. Or can’t talk about. Love it. They never dwell too long in the shadows, but those are the songs that got me through my teenage years.

I would contend that psychedelia, with SPLHCB as its most foremost explicit statement, was a *critical* political movement, pointing to the fundamental inadequacy of “straight” society and middle class bourgeois values… I also like your formulation, bright on the outside and dark on the inside.

This duality, and complex relationship to reality, is what makes the movement which culminated in psychedelia/the “Summer of Love” (and decayed after that) a really authentic political artifact, rather than one of style or fashion.

It, like a lot of its constituent movements–everything from the Beats to improv to jazz to the New Frontier to CND to the Acid Tests–was forced into being by the horrors in the straight society. It was an attempt to solve the problems that straight society couldn’t, or wouldn’t, solve, whether that was Ginsbergian freedom to be an individual or Second City/Beyond the Fringe’s insistance on political critique through comedy or “Blow-Up”‘s sense of hollowness at the core of political reality.

Prior to the introduction of chemicals–first marijuana and then LSD and ilk–the packaging of this dissent was very straightforward. Even the comedy of the late 50s/early 60s has a kind of earnestness (which is why Peter Cook is so remarkable). Anyway, events after 1963 gave things a desperation which hastened the use of chemicals. Those chemicals gave the movement two things: a sense of whimsy, and a feeling of rightness. And there was a great deal of energy imparted from the LSD experience itself–the “expansion” part of it.

Pepper is, I think, all these things. It is energetic as hell. But it’s also a clear-eyed look at the seemingly intractable questions of identity and morality, and alienation from same–there is existential terror in Pepper. This is, perhaps, the “hole” that needs to be fixed. It certainly is what drives the girl to leave home. It is “nothing to do but call the wife in/nothing to say but how’s your boy been.” It is the enlightened guru telling you you’re lost and it’s the everyman responding that he’s just trying to get by with a little help from his friends. Pepper’s NOT hippie kitsch–and it’s this darkness that makes it so. War is; empire is; time passes; there is sickness suffering and death all around.

So what do we DO about it?

Pepper is ALSO a positive, art-based response to all these things. We take a military band, get them high, and dress them in Day-Glo satin. We declare the old Empire dead–for by 1967 it surely was–and declare a new one based on art, sexual freedom, youth–the currents of Swinging London. Time passes–one day soon we WILL be 64–so we collect a menagerie of like-minds and fellow travelers (the cover) and draw on them for comfort and possible solutions. There is sickness, suffering and death; but I’d still love to turn you on.

Even though that cheerfulness was eventually crushed, and the rickety skeleton of goodwill and hope and enthusiasm toppled before real muscle could be laid on it, psychedelia was based on some eternal truths. Whether those truths come from Owsley Purple or the Sermon on the Mount matters very little. Those truths still tell, even now, and Pepper–partly through genius and partly through timing–is the best, clearest articulation of that peculiar historical moment.

But isn’t Time the great yardstick to measure things by? How well things stand up years down the line? Some artists only get recognition after they have died, sometimes centuries after. Reading the reviews for Abbey Road (for example) on its release, and I’m surprised by some of the criticism there. But then that’s because the basic context the review was written in has changed so much in 50 years (inevitably).

Psychedelia particularly (as art rather than the experience itself) hasn’t dated too well. Like a lot of comedy, it’s too locked into its time for many people to really ‘get’. I don’t think the Beatles were necessarily writing with posterity in mind… And I don’t think something as revolutionary as ‘The Beatles’ could happen now, at least not in the song-writing/performing format. When they were writing, hi-fidelity sound recording (of the type we are used to now), was barely a decade old; so much had yet to be done with songs and recordings. It was a blank canvas in many ways. And they wallowed in it. It WAS a Renaissance, of sorts.

So the fact the Beatles popularity endures at all outside the context of the swinging sixties has to be testimony to the great feel that’s still there, in the music, for anyone, anywhere to dig, anytime. Surely?

Michael Gerber, I agree with everything you’re saying, but I wonder if the movement you’re calling “Psychedelia” could more appropriately be called the “Counter Culture.” Or perhaps, to be even clearer, the “1960s Counter Culture”? Psychedelia, besides the strict and literal association with drugs, also to me feels limited to music and visual arts, whereas “60s Counter Culture” is broad enough to embrace the period’s music, arts of all kinds, and expressly political and economic movements (leaving aside for the moment the question of whether the music and art were political). My own parents, for example, were indisputably part of the 60s Counter Culture (they were left-wing political activists), but the term “Psychedelia” would seem to exclude them and many people like them from the analysis. (And, by the way, they did buy a copy of Sgt. Pepper’s, which I’m proud to say I still have.)

Also, thanks for your response to my earlier comment about the 80’s. Yes, it was the *media* of the time that was drenched in complacency and shallow contentment. I, for one, was miserable then, as were many people in my family (of all ages).

@Mudarra, I also was miserable during the 80s, though that was more to do with being 15 than anything else. If I’d found someone to start a band with, I would’ve felt better, but being alone I had to write comedy instead. 🙂

You’re right that what I’m defining as “psychedelia” is a bit different–certainly more wide-ranging, more serious, and less about Day-Glo body paint–than what is generally meant by that term. But I use it because the psychedelic period (say, the years stretching between Ken Kesey’s bus trip and the assassination of Martin Luther King) is, to me, hugely important and vastly understudied.

The 60s counterculture stretched from ’63 to ’73; the psychedelic strain of that emerges first in ’64, and really hits its stride in the US and UK in ’66. By late ’67, media coverage of the Haight had crushed that scene; and by early ’68, we were on to something new. This shift, I think, was disastrous, and not wholly organic–and it’s what I hear between Pepper and White, for example.

The psychedelic period takes the earlier, mostly authentic, mostly unco-opted movements of Beat culture, folk music, Old Left politics, and gives it the energy of youth and Pop.

Here’s an example:

Boycotts and sit-ins (Old Left politics)

+ nonviolence (Beat culture)

+ youth (Kennedy-era optimism)

= Freedom Summer.

And here’s the important thing: Freedom Summer WORKED. It wasn’t theater or suburban revolutionary bullshit; it wasn’t the Chicago Seven trial or the Weathermen; it was an actual political movement springing from the heart of the American democratic tradition, which achieved its goals and improved people’s lives. That’s a huge difference between the politics of the early 60s and the late 60s; the early stuff worked, and the late stuff was good TV.

By mid-66, you also start to get the peculiar psychic signature of the earlier class of hallucinogens–the religious or quasi-religious experiences caused by peyote, mushrooms, or LSD. So there’s political power, plus a growing sense of “oneness.” In 1967, MLK comes out against the Vietnam War. Things are shifting, and they’re shifting fast.

Directly after the psychedelic period, here’s what happens:

–the drugs change from pot, peyote, mushrooms and acid, to harder, harsher stuff like STP, heroin, and speed;

–the politics change from nonviolence to violent revolution, a mistake for any outnumbered, outgunned group, and intellectual suicide for any basically pacifist ideology;

–the art changes from warm to cold;

–the music changes from psychedelia (which while full of excesses and plenty of drek, was an authentically new style) to electric blues, which was essentially the same old white-borrowing-authenticity-from-black.

During the psychedelic years, you have in the West both a fully formed youth culture connected to earlier intellectual movements AND a sense of optimism. After the psychedelic years, you have a fundamentally isolated and paranoid youth culture which largely dismissed earlier movements. Everything that has lasted about the 60s is from that earlier period, but has been replaced in the popular imagination by stuff from the later period, which was mostly bullshit.

Wot??

Heads desk.