- What John Lennon Thinks of Donald Trump - November 14, 2016

- The Meaning of Fun: The Paul is Dead Rumor - February 3, 2016

- BEATLES-STREEP-SHEA SHOCKER: IT’S NOT HER!!!! - August 13, 2015

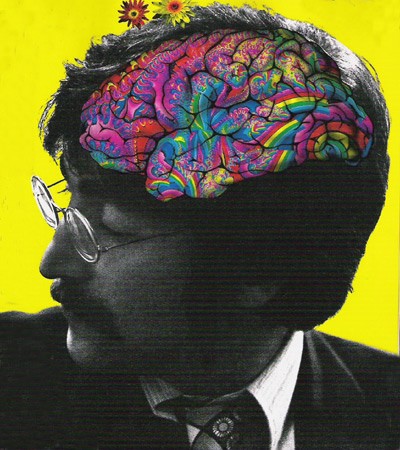

DEVIN McKINNEY • We all know you can take the Beatles to the outer limit and upper extremity of significance—Best thing in universal history—and then narrow that unit to its subordinate but still-impressive absolutes: Best miracle of the 20th century; best socio-cultural force of the 1960s; Best group of the “rock era.” Having accepted all of that, you can, and we all have, then go superlative in descending levels of specificity: Best album; best song; best vocal performance—John; best vocal performance—Paul; best bass playing; best guitar solo; best everything else.

But have we gotten down as far as we can go? Is there nitty-gritty still to be mined? Yes—always.

The scam

It occurred to me the other day while driving, and really getting into some singalong energy, that Beatles music is filled with micro-moments, flutters or flourishes that last a second or two, no more. Moments that don’t even “last,” really, because they are here and gone so quickly, leaving only that silver flash of amazed memory, that dazed and dangling desire for more.

Every Beatles fan feels the importance to the group’s music of these flashes and dangles. It’s not only complete songs or albums that make their picture, it is also moments—absolute moments. There are usually no lyrics to these moments, so they don’t have to make “sense”; they require no meaning in that (non)sense. There is nothing to comprehend in them, but plenty to feel. They are accidents of an instant, or expressions of momentum, or little atmospheric explosions in the midst of a maelstrom; yet they are indubitably heard, felt, absorbed, each time one hears them. At their best—when the accident is ordained, the instant inspired—micro-moments crystalize the impact and energy of the record in a priceless noise preserved in a sliver of time.

The list

In ascending order of favoriteness, with key points specified, these are my favorite Beatles micro-moments (click the song title to open the YouTube link in a new tab):

[Note: At some point in 2015, the conglomerate Universal Music Group made copyright claim to the Beatles’ music, resulting in the blanking of the You Tube videos linked here. Many of the official Beatles videos are now available on Vevo, but those are often different from the commercially released studio versions referenced here. But you can still play along, using CDs and headphones, and following the timings.]

Heard at 2:57. I’d understood for years that there was a muttered profanity buried somewhere in the backing layer of this, one of the Beatles’ greatest, and most pious-seeming, songs. That always sounded to me like a rumor someone felt they had to invent. I could hear the mutter, and comprehend it as a curse, but only as I could see the “black dog man” on the grassy knoll, or Beatle faces in the tree branches of John Wesley Harding: it was there if I was looking for it. Then I read Lewisohn’s Recording Sessions, and urban legend was confirmed: “Listen out for an undeleted expletive at 2’59” into the finished record!” Tastefully, Lewisohn didn’t repeat the offending phrase, but it is, as most of us know (or believe), “Fuckin’ hell.” Lewisohn did not, however, tell us who says it, or why. Is it John hitting the wrong chord? Paul hitting the wrong chord? Neil Aspinall tripping on the tea service? The curse is confirmed, but the mystery remains.

Heard at 2:16. Nancy has written movingly on this site of Paul’s gift for writing “songs of empathy.” Another manifestation of his empathy is his enthusiastic background interjections on other people’s songs. He is heard throughout this underrated tune of George’s, and at this particular moment, apex of the song’s wicked, witty buildup—a near-parody of rock intensity that is also the real thing—Paul, clearly carried away, not calculating at all, just shouts “Yeah!” and sets everything free.

Heard at 2:22. Where, instead of “gun,” John sings “gah-oh-wah,” followed by the crash of the band burning up the home stretch. Savagery, hilarity, complete commitment to sound over sense. The White Album is loaded with micro-moments; “Revolution 9” is almost nothing but. Did I tell you it’s my favorite Beatles album?

Heard at 0:01. The opening guitar note, played by George on a volume-tone pedal, is a plunging, velvety invasion, a soft hand reaching deep inside me, perhaps to remove my heart; the sharper notes that follow bring a soft sear of pain to this creepy, haunted dream.

Heard at 1:39. The harpsichord-bass figure folds inward beneath the last line of the last verse like submissive hands, or a hopeless soul: a death just as final, and far more painful, than the last chord of “A Day in the Life.” This is a brilliant bass performance from Paul: through most of the song his notes are hit straight and clearly enunciated, but notice how on the last verse—the lyrics saddest, the death of the heart settling in—his notes melt at the edges, each descending line leaning down into the next, in a magnificently subtle rendering of sorrow and surrender.

Heard at 1:32. Far more than the orchestral buildup, Ringo’s drumming imparts doom. His fills are threatening shuffles coming from shadows, jousts and fake-outs, little acts of terror barely perceived by the oblivious singer-wanderer. So gripped by the Lennon vocal, fragile in its echoed suspension, we might ourselves fail to register the drums’ entry at the second verse. But Ringo, master “bricklayer” (in Albert Goldman’s moronic dismissal), builds on the intensity of each verse until finally, at this moment, just before the no-turning-back of the first crescendo, we hear his final fill and cymbal hit—and to me it has always been the sound of “Abandon all hope.”

4. “The Ballad of John and Yoko”

Heard at 2:56. I love the modest drum “plop” that ends this record. It’s the essence of a down-beat, a full stop, a happy gesture of depletion capping a deceptively simple number that has in fact been rising in mad energy with each verse. As a drummer, Paul had clearly learned a thing or two from Ringo. (Note that in some mixes on some records, the last chord is faded prematurely, the “plop” stop only barely audible; it’s that way on the Hey Jude album, whereas on the 1967-1970 compilation, where I first heard this song, it is fully sustained.)

Heard at 2:50. Excepting “Lovely Rita” and “A Day in the Life” (of course), the whole of Sgt. Pepper strikes me as inferior to this neglected, apparently nonsensical B-side. (Though not neglected by David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin, who made keen use of it over the end credits of The Social Network.) The Beatles are clearly deep into it, feeling their own malevolent energy, tasting the taunting lyrics, focusing their post-acid energies on a long dark studio night. The John-Paul vocal interchange on the fade rehearses for “Hey Bulldog,” with the micro-moment of Paul’s “Whoo-hoo!” taking the song into third gear just as it speeds out of sight.

Heard at 2:22. The bastardized Capitol rendering—globally despised, like everything else touched by the hands of Dave Dexter Jr.—is one of my very favorite Beatles recordings. The Capitol version adds smoggy reverb to the crazy-but-clean Abbey Road original, and lands it on another level of early-Beatles intensity. Just love, love, love, love it! Anyway, the crash-and-bang of the sound, the Gary “US” Bonds lunacy of the overall, has always deceived me into thinking there were more instruments at play than just the Beatles’ basic line-up—which of course is not true at all. But I could always swear that at this point in the song, when things are climaxing, I hear a flute. Yes, a fucking flute. I still hear it, though I know it’s not there. My mind provides me with that little extra touch of beauty, a taradiddle amid a magnificent chaos.

Heard at 3:11. Ringo crashes the cymbal right here—in the wrong place. I mean that rhetorically. It is actually the right place—just the right place—but a right place that more conventionally skilled and cliché-comfortable rock drummers would never think to reach. The chord sequence on the refrain of “Real Love” is C-Am-F-G. The cymbal crash is a classic rock signifier communicating climax and commitment, the peak point of a performance, and most rock drummers would, in Ringo’s seat, have placed it squarely at the top of the sequence, on the defining C—where it would shine like a plastic star atop a Christmas tree, or the eye at the point of the pyramid. But Ringo, gut genius that he is, hits his cymbal on the F—that is, not on the achieved peak of the base key, but on the aspiring major that springs from and leads back to it. That expands the emotional impact of the cymbal enormously: it comes when the song, and our hearts with it, are not standing on the summit but reaching for the summit, grasping upwards.

Additionally, where the rock cliché would have placed the cymbal crash upon the recovery of the C chord, and lyrically on the last iteration of “real,” Ringo’s crash coincides with the word “love.”

I love Ringo.

The call

Dullbloggers, share your own favorite micro-moments. Only one rule: It can’t last longer than two seconds.

In Hey Bulldog, there is some beautiful ad-libbed madness with John barking like a dog. At one point, he stops and asks “what do you say?” There is a brief woof. “Do you know any more?” and this is followed by a howl.

The “do you know any more?” is one of those moments for me.

If the real Beatles had been motivated enough to provide the voices for the Yellow Submarine movie, rather than those ridiculous voice-over actors, we’d have something truly wonderful. I would have given them scripts, plenty of rum and coke, some giggle cigs, and let them have at it.

And isn’t there ADT on the “do you know any more”, which is a totally random thing to do but adds authority to something that was probably improvised?

There’s an actual yawn in one of the breaks during “I’m Only Sleeping” – barely audible at normal volume but it’s there.

I love the single “ping” on a finger cymbal at the start of “Dear Prudence” (0:19), which comes at the same time as the first bass note. I always listen out for that one.

I’m not sure whether to like or dislike the fact that they left in John’s misplaced “yeah” towards the end of “Day Tripper” when they start to repeat the song title – was this “overlooked” on purpose or did the simply not care?

Devin, this is such a wonderful post.

@Velvet, I love that yawn, too! I’ll keep thinking, but that’s certainly on my list. I also like the ghostly “she feels good” by Funny Voice Lennon at 1.27 of “Good Day Sunshine.”

http://youtu.be/kRdtKUWn_wI

After Paul sings, “She feels good…” it always sounded to me like John mutters, “She does” and you can almost hear a smile in Paul’s voice as he continues singing, somehow able to keep from laughing.

Great post, great topic, and one I’d thought about quite a bit before.

I think Abbey Road alone s littered with these moments.

Golden Slumbers: “Smiles awake you when you rise” http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=VpV53LqcuhU#t=2536 – Sweet, pure passion from Paul (OK, that’s five seconds, but the really good stuff — “smiles awake you” — is just two.

Carry That Weight: Ringo leads the chorus, out of the blue. His voice just pops out,

Maxwell’s Silver Hammer: Paul’s laugh, mid-verse. http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=VpV53LqcuhU#t=523

Really every twist and turn of the medley, but that’s almost a collection of micro moments built into macro moments, difficult to split it up.

@Devin – As far as the Hey Jude moment above, Geoff Emerick says its Paul, something he heard second-hand from 2nd engineer John Smith. From page 263 of “Here There and Everywhere”:

“Paul hit a clunker on the piano and said a naughty word,” Lennon gleefully crowed, “but I insisted we leave it in, buried just low enough so that it can barely be heard. Most people won’t ever spot it… but we’ll know it’s there.”

I always liked the faint “hoooo!” that pops in at the middle of the stereo spectrum in the original stereo of I Want to Hold Your Hand. It comes in the midst of the last “hide” of the second refrain and sounds almost like an attempt to give it a She Loves You feeling. It’s very quiet.

Then there’s the electronic blip in the stereo Tomorrow Never Knows that occurs in the middle of “That love is all and love is everyone” but absent in the mono. (Yes, this is technically a mastering error, but it’s cool.)

I love the faint “Thank You!” by John (in Funny Voice mode) at the end of “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da.” It’s the ideal semi-ironic ending to the song. John might have called it “granny music,” but he provided both of the song’s perfect bookends — this ending and the banging piano intro.

Another favorite of mine is John’s “Good evening, and welcome to Slaggers” in “You Know My Name, Look Up the Number.” In fact I love ALL of John’s ad-libs.

I also second Velvet Hand’s fondness for the finger cymbal and bassline intro of “Dear Prudence.” And add the way Paul’s voice breaks when he tries to hit the high note in “you” in “If I Fell.”

Finally, it’s too long to qualify under the guidelines Devin established here, but Paul’s song snippet between “Cry Baby Cry” and “Revolution 9” (“Can you take me back where I came from / Can you take me back . . . .”) is haunting and heartbreaking, especially in the context of the “tension album.” An album where the band members were nevertheless contributing beautifully to each other’s songs.

What I think is Lennon coughing or clearing his throat as the final chord of “Twist and Shout” fades out. Evidence to what extent he’d just shredded his vocal chords in what I think is the best rock n roll vocal ever.

LOL! I always thought it was sneeze!

Can’t stop posting… what a lovely topic.

Paul hitting a wrong note on the bass during the long outro to “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”. I recently heard the Rock Band mix for the first time, and they’ve actually CORRECTED it – the shame, the shame.

Paul hitting a wrong chord on the piano in “Let It Be” (I think it’s just after “I wake up to the sound of music”) and instantly correcting himself. I’m fairly sure there’s a version of this recording too where this bit has been “sanitized”, but don’t know which one – it’s not on Naked as that’s an entirely different take…

The one word in “Only a Northern Song” (“…if my hur is BROWN”) where George harmonises with himself rather than singing the same note on both tracks.

The very slight pitch correction at the start of the piano bit in “The End”.

Ringo’s voice breaking in “Good Night” – can’t be sure right now exactly where in the song this happens, but it’s almost like he’s cracking up with the strain of trying NOT to crack up in the face of all the weird stuff that’s gone before on the album.

@Mike: That yawn is so awesome that the Stones tried to copy it a year later on “In Another Land”, but it came out as a snore instead.

In Another Land came out before the White Album.

Hmyes, but Revolver came out before Satanic Majesties… 🙂

Thank you, Mike, and thank you, Dan, for setting me straight on “Fuckin’ hell.” So many books I’ve never had time to read, and Emerick’s is one of them. But even it the mystery is solved, I still like the contrast of a swear word behind that particular song.

Anybody know what caused the flatulent “blaaap” sound at the fadeout of “Do You Want To Know A Secret”?

I love John’s sotto voce asides! One of my favorites is his “We told you why” after Ringo sings “Tell me why” in “What Goes On”

So many Paul ad libs to choose from!

The following two are truly micro, but i like them because the Beatles were so restrained in their first recordings. In Love Me Do, such a buttoned-up song, I love Paul’s little “hup” right before the harmonica solo at 1:28. And when he and John come back with the vocals, his extra lilt on ‘love, love me DO!” at 1:51. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_M9US-cXJMo

I can’t hear the “yeah” in Old Brown Shoe, but I’ll keep trying…I think it’s a generous thing to do on his part, to vocalize freely on someone else’s song without upstaging. But you know I’m a Paul fan.

John’s “Take four hundred and forty four!” before “Christmas Time Is Here Again”

This is the kind of Beatle chat I adore so thank you! I just love the version of I got a feeling from Anthology 3. Paul’s vocal range, John’s daft backing, not to mention the breakdown chat. It’s an amazing take but 50 seconds in, the fabs and Billy absolutely nail that drop. Sublime, I rewind it again and again and again.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BusbQ5D1i1Y

@jimibob: Nice.

OK! If solo stuff is legal, I have just found my NUMBER ONE ALL-TIME FAVORITE micro-moment!

At around 2.13 of this recording of “Crackerbox Palace,” George says, “It’s twue, it’s twue!” a shout-out to Madeline Kahn in “Young Frankenstein.”

http://youtu.be/BZlKT-QwZIQ

I know this only 7-years late, but the movie was Blazing Saddles. Both movies did have Gene Wilder though.

Sorry! Thank you.

These are all fabulous. I’m going to take an hour tonight and listen to them all on repeat! One thing about the “Fucking Hell” moment on Hey Jude. I’ve never understood why there was any mystery behind who says it. It’s clearly Paul’s voice. It doesn’t sound like John at all.

“Paul, clearly carried away, not calculating at all, just shouts “Yeah!” and sets everything free.” I LOVE when Paul does that. He’s on a few tracks getting carried away like that. He’s such a fan. 🙂 And he really did like Old Brown Shoe. He’s been quoted several times about how much he likes Old Brown Shoe.

“Don’t Bother Me”

George is faintly heard saying at 0:03, “It’s too fast.”

John flubbing his line at one point in “Please Please Me”. At about 1:25 he’s supposed to sing “I know you never even try, girl” but says “I never even try” (Paul sings it correctly). Then after the drum fill that follows it sounds like he’s stifling a laugh at “C’mon…”

Always loved the doubled”We all want to change your head HEAD” in Revolution

I love when John sings the versus to Yer Blues off mic at the end of the song. Or what about the ghostly voice at the end of “Long Long Long” that makes an already spooky song even more so? I think that song is so underrated, but at times I feel that George’s vocal gets buried in the mix.

Ooh, a post I hadn’t seen with so many great moments. Thanks, Recent Comments, I shall seek out all the ones I don’t know!

.

I’d like to add something that runs throughout the entirety of “Boys” on Please Please Me but each instance is a second or so — Paul’s background screaming. The first time I really heard those I was like wha–? Turn that up! Lessee, there’s one at :32, and one at 1:05, and 1:19, and on and on. I picture them all playing, recording those takes live, and Paul stepping back from the mic to shriek now and then. They must have been having a blast, and it gives us a glimpse, like that entire album, of their sheer energy in the early days.

Seek out Devin’s posts, @Kristy. They are great. 🙂

I’m partial to early Beatles. The energy makes you want to get up and dance. So infectious and the reason they became the biggest band in the world. IMO if they debuted with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, we wouldn’t be talking about them today.

I know this might be blasphemous to some, but I really like the false start on “I’m Looking Through You” on the American rubber soul, accompanied by what sounds to all the world like a car engine turning over:

John, Paul, and George’s intersections on the second time through the bridge of “PS I Love You”:

J: Oh!

P: You know I want you to–

G: Yeah-ah-h

https://youtu.be/MA5DkiVKSlM

One of my favorites is the false start on Mr. Moonlight. (I think the outtake that includes it is on Anthology) John tears off the opening phrase, which he has to do from a cold start without even a count in. He skids immediately to a stop and grumbles, “no, no.” And Paul, surprised, says, “really? I thought it was rather good, that.”

It’s a moment that shows John’s (needless) insecurities about his voice and Paul’s steady reassurance and support. It’s lovely.

Also, Hard Day’s Night 1:55:

Paul: “feeling you hold me tight…. tight, yeah”

John: “Mmmmm”

These are so great.

This one just about comes in under 2 seconds: the moment in Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise) where they go “Sgt. Pepper’s one and only Lonely”. It gets me every time.

I love that one, too! As a songwriter, I adore the alliteration and repetition.

Related, at the end of the reprise, there’s another micro-moment — Paul’s crazed scatting… which is only audible on the mono mix (the only way to listen to Pepper, of course — so many details only audible on the original as-the-band-intended mono mix).

FYI, I just read the “Hey Jude” entry in McCartney’s The Lyrics and Paul confirms that it’s him saying ‘Fuckin’ hell” and that it’s because he messed up the piano part. There’s also a great story in there about Ringo during recording. Here’s the excerpt:

“A funny thing happened in the studio during the recording. Thinking everyone was ready, I started the song, but Ringo had run off to the toilet. Then, as we were recording, I felt him tiptoe back in behind me, and he got to his kit just in time to hit his intro without missing a beat. So even as we’re recording it, I’m thinking, ‘This is the take, and you put a little more into it.’ We were having so much fun that we even left in the swearing about half-way through, when I made a mistake on the piano part. You have to listen carefully to hear it, but it’s there.”

The moment at 1:05 in “Boys” when Ringo yells “alright George!” and plays a fill that coincides perfectly with the beginning of George’s solo. It’s so flawlessly synchronized it’s as if they had been playing together for ten years instead of only five months.

Okay, because I’m supposed to be doing my taxes and I don’t wanna and this is so much more fun, two more, these from one of my favorite Beatles albums, Everyday Chemistry (which I definitely consider to be a Beatles album, albeit a very strange one):

1. John’s count in on “Jenn” and his “here we go then” — he sounds so happy and there’s an energy to that moment as the synth builds and the band launches in that always makes me smile because I imagine in that alternative universe how happy they all are to be finally making music together again. I can just picture them all smiling a huge smile of relief to be back where they all belong, making music together. It’s one of my all time favorite Beatles moments even though it’s a fantasy.

2. The studio chatter at 1:33 in “Soldier Boy.” This time, it’s all four of them, and again, they and particularly John sound so full of life and joy, and there’s a special energy there that I think is reflective of the best of what they were. (I esp love the inclusion of the “shut up” from “shut up while he’s talkin'” — always makes me smile.

If you haven’t checked out Everyday Chemistry, I promise it’s worth your while. Even if you’re not entertained by the origin story, it’s first-class work. I listen to it frequently and I’m not exaggerating by much when I say that if I could only have three Beatles albums, it would be Revolver, Abbey Road and Everyday Chemistry. (“I’m Just Sitting Here” is probably my favorite track, but there are no bad tracks on it.)

I don’t know if we’re allowed to post links, but the original download link is here: https://thebeatlesneverbrokeup.com/