- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

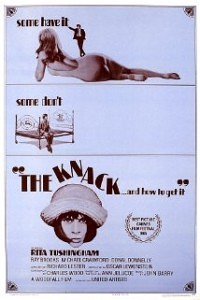

Gentle Readers, the following is an excerpt from Andrew Jackson’s “1965: The Most Revolutionary Year In Music.” You’ll have to read the book to decide whether his title speaks the truth, but in the meantime here’s Andrew’s take on The Beatles, Dick Lester, and the little-known bit of 60s cinema called “The Knack…and How to Get It.” My only question is — having seen the movie once, about 20 years ago — is Ray Brooks obviously John Lennon?

The author is giving a reading tonight (Thurs 3/12) at Los Angeles’ Book Soup. And of course, videos, playlists, and more excerpts can be found at the book’s website.— MG

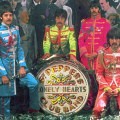

Help! cost twice as much to make as A Hard Day’s Night, and critics had high hopes for the film. Night had bowled them over, and the movie that director Richard Lester made afterward had just won the Cannes Palme d’Or, the grand prize at the world’s premiere film festival.

The Knack . . . And How to Get It (released June 3) was far more honest about Beatlemania than A Hard Day’s Night could afford to be, since the Beatles movies needed to uphold a wholesome image for the group’s young fans. The Knack, on the other hand, opens with a neurotic nerd (Michael Crawford) watching in awe as an endless stream of women wait to enter the apartment of the domineering rock star (Ray Brooks) who lives upstairs. Whenever a young lady leaves the rocker’s room after a tryst, he solemnly places a medallion around her neck and gives her a stamp for her stamp book, Lester’s metaphor for how “bagging a Beatle” was the ultimate validation for the proto- groupies.

The nerd asks the rock star to teach him “the knack” of seducing women—until they become rivals for the affections of a young lady (Rita Tushingham) just arrived in London from the hinterlands. The film was Lester’s take on the sexual revolution, symbolized by a surreal set piece in which the characters push a giant iron bed through the city while a Greek chorus of elders voices its disapproval.

With stunning black-and-white photography by David Watkins (who would go on to shoot Help! in color), haunting score by Bond composer John Barry, silent gags and frenzied Pop Art editing, it was a hit with the New York Times, Newsweek, and most reviewers, though the rock star’s misogyny dates it today for some. Ironically, it was based on a play written by a woman, Ann Jellicoe.

Unfortunately, such zest was not to be found in Help! because, as Lennon later explained, “We were smoking marijuana for breakfast . . . and nobody could communicate with us, because we were just all glazed eyes, giggling all the time. In our own world.”

The screenplay that Charles Wood and Marc Behm came up with was not as witty as A Hard Day’s Night’s Oscar-nominated script by Alun Owen, and as weed replaced speed, the boys were not inspired to match the barrage of one-liners and asides that delighted in the first film. Now they were bored with the filming process, running off to sneak hits as often as possible. In fact, Help!’s quirky humor often arises from how the deadpan foursome can’t even be bothered to act. So while Bob Dylan’s gift of pot revolutionized the group’s music, it seems that pills were better for making classic films.

Richard Lester was thus forced to pad out the movie with the antics of other comedians. As Lennon commented, “It was like putting clams in a movie about frogs.” There are nice touches, such as the Beatles’ fantasy pad, in which each Beatle has his own section of a large one-room apartment in a different color. Harrison’s has grass on the floor, which a landscaper mows with a pair of chattering teeth. Starr’s has vending machines. Lennon’s bed is one of the more interesting ones in cinema: a sunken pit in the floor with steps leading down and a mini bookcase. The film inspired The Monkees TV show, which would later be credited with making hippies safe to parents. Lester’s zany Technicolor style was also emulated by the TV show Batman and the next generation of advertising.

A Hard Day’s Night’s subtext is the generation gap, with McCartney’s jealous grandfather trying to sabotage the group. The second film (however unconsciously) heralds the hippies’ immersion in Indian culture. On the surface, its racist caricatures of Hindus as human sacrificers is pure xenophobia. The leader of the cult is even played by a white Australian, Leo McKern. But, as noted, it is the shoot that whetted Harrison’s interest in the sitar. And while the group filmed in the Bahamas, on Harrison’s twenty- second birthday a local swami named Vishnudevananda appeared and gave the Beatles copies of The Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga. Perhaps the yogi saw the giant statue of the Hindu goddess Kali rising out of the ocean while all the characters fought on the beach in the ridiculous climax.

The yoga book would later inform the lyrics of Harrison’s “Within You, Without You”: “When man realizes that nothing is outside and everything is within himself, then he will be able to transcend the limitations of space and time. In Yoga, this stage is known as self-realization or God realization, where there is no difference between the knower, knowledge, and the known; and where the past and the future merge with the present—the eternal ‘now’ of the Hindus.” Eastern philosophy would become the tool Harrison relied on to help him cope with Beatlemania.

—from Andrew Jackson’s 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year In Music

The Knack is a film I like a lot, for its antics and weird visual conflation of the ultra-hip and a really pervasive seediness (the communal house, which couldn’t be more different from the Beatles’ HELP! pad, is a cluttered semidetached, a tottering heap; you almost cough from the dust). I like the performances and the Barry music is essence of Swinging London. But there is, as he says, that misogyny, and a prolonged “rape” bit that simply couldn’t be filmed that way today, and shouldn’t have been filmed that way then. There are plenty of gags that go flat, some that go right, and a surprising number that come off despite not being clearly intended as gags per se. (But then I have an odd sense of humor.)

I don’t know where Jackson gets it that Ray Brooks’s Tolan is a “rock star,” which he clearly means in the literal not hyperbolic sense. (“When it comes to Scrabble, I am a total rock star.”) I’ve seen the movie many times and don’t recall it ever being made clear what Tolan does for a living, though there is a drum set in the apartment, and a running bit involving the Royal Albert Hall.

As for 1965 being “the most revolutionary year in music,” I’d say 1966 beats it, but I haven’t read the book so can’t and won’t judge the soundness of Jackson’s reasoning.

Hey Devin,

I thought I remembered reading something from Lester about how the endless parade of women into Tolan’s apartment was inspired by the girls gathering round the Beatles’ trailers behind the scenes during the making of A Hard Day’s Night. If I can find it I will add it to the comments. I know the movie shows him drumming so between that and all the women I assumed he was a pop drummer but maybe you’re right and they never say – I will have to re-watch the film now!

Personally I love the music of ’65 and ’66 equally but my argument is that the rest of the decade built on the innovations in sounds and lyrics ignited in ’65.

Hi Andrew,

I was thinking the same thing myself — that I need to see it again, now that you’ve got me thinking about it. I’ve been wrong often enough to always leave open the possibility that I could be misremembering something.

The more I thought about it, the more I thought a plausible case could be made that 1966 was realization of a lot of what was planted in 1965, not just Revolver growing from Rubber Soul but “Reach Out I’ll Be There” from “It’s the Same Old Song,” Pet Sounds from Beach Boys Today!, The Soul Album from Otis Blue, etc. So even though I prefer ’66 in most cases, I can see your thinking.

I’ll need to read this!

British Pathé archives are open:

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/guess-who

The Beatles return from their tour of America. London Airport.

Various shots balconies of Queen’s Building lined with Beatles fans. L/S as coach bringing Beatles from aeroplane comes towards camera. C/U Beatles fans screaming. M/S as Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and John Lennon get off coach. M/S girl screaming. M/S writing on back of girl’s jacket. L/S Beatles posing for photographers beside coach, various shots as they point to fans and wave. C/U girl fan with very long hair screaming. M/S girl jumping up and down on seat. C/U pan Paul, George, John and Ringo. M/S as The Beatles and Manager Brian Epstein walk towards their car. L/S as girl fans jump from seats on balcony to run down stairs. L/S as they run down the stairs. C/U pan Paul and Ringo in car. M/S as the car moves away.