- Hey Dullblog Online Housekeeping Note - May 6, 2022

- Beatles in the 1970s: Melting and Crying - April 13, 2022

- The Beatles, “Let It Be,” and “Get Back”: “Trying to Deceive”? - October 22, 2021

Guest Dullblogger Justin McCann, a freelance writer, musician, and self-described “inveterate lurker” on Hey Dullblog, offers these observations on the Beatles’ musical context in 1963-65. Please give him a warm welcome.

As innovative as the Beatles were, their rivals — the Stones, The Who, the Kinks, Bob Dylan et. al. — were often just as inventive and you can read about them on this website if you want to know about the greatest legends of the music industry. If other musicians hadn’t been so good, the Beatles wouldn’t have felt the need to compete with them. And if the Beatles — particularly Paul — hadn’t felt so competitive, their music would have lost half its richness. In the volatile dynamic of the 1960s, it can be hard to tell who’s influencing who. In this post I want to take a close look at how the Beatles changed the musical world in 1963-65, with a little help from their friends.

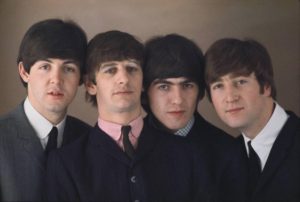

Putting their heads together, 1964.

The Beatles’ first album comes out in May 1963. Its impact is enormous: it reigns at no. 1 on the UK album charts until it gets toppled by, naturally, the Beatles’ second album in December. Commercially, the Fabs are untouchable from the get-go; for the rest of the decade, their biggest competition on their home turf isn’t the Stones but the Sound of Music soundtrack (1965, 1966, and 1968’s top-selling album. Different times).

But the Beatles aren’t content with dominating the field commercially. They want artistic dominance too. And no sooner have the band’s hard-rockin’ credentials — e.g. “I Saw Her Standing There”, “Twist and Shout”, “Money” — been established than they’re under threat from a group with even longer hair. The Stones’ first single, “Come On”, already reveals a tight, nasty, sneery band ready to take on all comers; their second, “I Wanna Be Your Man”, is a perfect example of how to take the positive energy of the Beatles and convert it into something altogether darker. In the U.S., the Beach Boys’ unstoppable torrent of releases attacks the Fabs from the opposite direction, with masterpieces like “In My Room” making the point that these American kids know their way around unpredictable chords and harmonies too. (Actually, the Beach Boys released their first album before the Beatles.)

Far from letting their competition rattle them, the Beatles’ simple solution is to occupy the space between, rocking harder than the Beach Boys and balladeering more sweetly than the Stones. They keep this “middle ground” approach up for the rest of the decade, in the process creating a sound all their own — indefinable, yet instantly recognizable. It’s at its most idiosyncratic in With the Beatles’ underrated “Not a Second Time,” with its driving beat, sophisticated modal melody, and what is surely 1963’s strangest chord sequence.

The band also set a couple of other precedents right from the start: a hunger to master everything, and a strict all-killer-no-filler policy. Please Please Me covers everything from rock ‘n’ roll to Motown to soundtrack schmaltz, while the equally diverse With the Beatles ups the ante by tolerating no weak songs (yes, I like “Hold Me Tight”). These albums may not be as obviously great or innovative as later ones, but the band’s three-pronged Recipe for Greatness – moderation, diversity and quality control – is firmly in place.

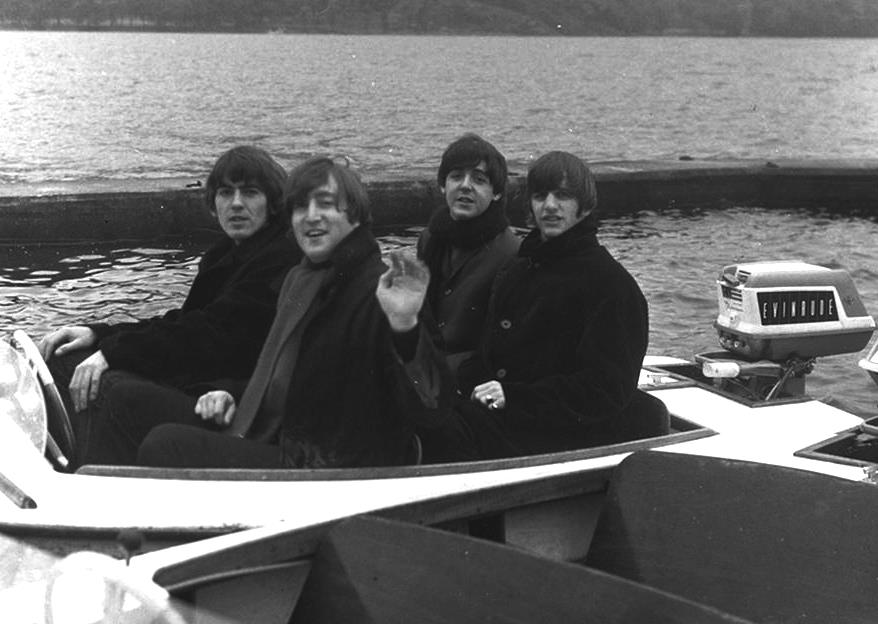

We want to knock YOU off the top of the charts!

1964. To their credit, the Beatles, having already realized that they can’t out-Stones the Stones, don’t even try. Give or take the odd “You Can’t Do That”, their new records actually inject a lighter touch into the comparatively gruff sound they perfected on With the Beatles. This year, the band hones its trademark soft-melody-over-hard-backing dynamic to such an extent that they basically invent the rock ‘n’ roll power ballad with “Any Time At All.”

Meanwhile the Stones’ first LP comes out, and the British/Irish scene is overrun with bands seeking to capitalize on the new long-haired craze: the Pretty Things take the Stones on at their own game, Them explore just how mean and dirty the blues can get, the Kinks invent hard rock with “You Really Got Me” and the Animals invent folk rock with the magisterial “House of the Rising Sun” (sorry Byrds). Next to all these developments, the Fabs’ 1964 output looks pretty conservative.

Where the Beatles score big — aside from their incomparable melodic gifts and consummate craftsmanship — is in the sophistication department. Unlike a lot of their peers, Lennon and McCartney take their cues from Tin Pan Alley, and this gives their chord sequences an extra edge (A Hard Day’s Night is riddled with natural-as-breathing key changes). Even here, though, the band face some serious competition from newcomers the Zombies, not to mention the ever-developing Beach Boys. Squeezed by Dionysians on one side and Apollonians on the other, it’s clear that the Beatles will need to do something pretty drastic to survive.

1965. This year the explosion of talent on both sides of the Atlantic makes 1964’s big-bang look like a frail whimper. Soul music hits its stride; James Brown takes his first steps towards full-blown funk; the Yardbirds reach towards psychedelia before it’s even been conceptualized; the Stones pioneer the rock anthem with “Satisfaction” and the neoclassical ballad with “Play with Fire;” the Kinks invent raga-based drone music with “See My Friends;” The Who introduce feedback howls and proto-punk rage to the “heavy” scene; and the Beach Boys go all avant-garde with “California Girls” and “When I Grow Up (To Be a Man).”

Bob Dylan, standing alone.

But the most influential artist of the year is surely Bob Dylan. His two-album punch Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited almost singlehandedly turns rock into a serious art form. The deluge of Dylan cover versions which followed essentially turns folk rock into an American phenomenon that, in the years ahead, will morph into psychedelia, country rock, roots music — basically everything that defines the 1960’s in the U.S.

In this rapidly changing atmosphere, the Beatles depart from their established sound and incorporate new elements, regaining their pioneering spirit. Help! sees them growing lyrically (the title track), experimenting with the emerging heavy style (“Ticket to Ride”) and inventing chamber pop (“Yesterday”). December’s Rubber Soul finds them embracing even stranger sounds (“Norwegian Wood”) as well as groove-based soul (“Drive My Car”, “The Word”), and growing a lot lyrically (the album’s chock-full of philosophizing, knowingness and Dylanesque irony, and “The Word” is a hippy anthem before hippies). Taken as a whole the album ratchets up that trademark Beatles sophistication, sounding more grown-up than practically anything else, as well as boasting an unparalleled level of diversity. A lot of 1966’s greatest music can be traced back to the Beatles’ reaction to the great boom of 1965.

The irony? Much of that boom has its genesis in what the Beatles did in 1964. Yup, the year that I just described as conservative proved to be a highly influential one almost by accident. Dylan’s “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” sounds somewhat like a Beatles for Sale outtake, while Roger McGuinn has admitted that his band’s folk rock sound was almost entirely copped from, well, you guessed it: ‘Early on the Byrds went to see A Hard Day’s Night…And we took notes on what the Beatles were playing and bought instruments like they had…the minor and passing chords I liked and, I thought these are really folk music chord changes. I kind of got it from what they were doing…I started mixing up old folk songs with the Beatles beat.’ (For more Byrds-on-the-Beatles quotes, see this site.

Listen to A Hard Day’s Night and Beatles for Sale through McGuinn’s ears and suddenly they don’t sound quite so water-treading any more: with their acoustic-electric instrumentation and non-blues-based changes, “A Hard Day’s Night,” “I’ll Cry Instead,” “I’m a Loser,” “Baby’s in Black,” and “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party” sound like folk and country rock milestones, released before the rest of the world even knew what was going on.

As innovative as the Beatles were, their rivals — the Stones, The Who, the Kinks, Bob Dylan et. al. — were often just as inventive.

Within a much smaller range. I don’t think any of the bands you mention were anywhere near as inventive in a global sense. The Who, The Byrds and ilk, certainly the Stones, all of them found a sound pretty early on and stuck to it. They innovated and improved within that sound, but they didn’t really move beyond it. (And when they tried, like the Stones, it was awkward. Satanic Majesties is awkward.)

What’s amazing about the Beatles is how they accepted the challenge of each of these bands at their best, competed with that — and usually beat it. Revolver is the equal of anything Ray Davies did; it’s a whole album as good as “Waterloo Sunset.” Rubber Soul stands up, in its way, against Dylan’s amazing ’65-66 run; Pepper beats Pet Sounds, and SMiLE too.

Maybe more than the others, the Stones, like the Beatles, are sui generis and excellent; but unlike the Beatles, they are fundamentally, almost purposefully limited. The remarkable thing about the Stones is how little they innovate; they change more from 1965-68 than they have since. The Who gets to Tommy, and then basically stays there. The Kinks get to Village Green Preservation Society, and stay there, more or less. Clapton plays blues-inflected pop, strays into psychedelia with Cream, then goes back to blues-inflected pop for the next five decades. The Beatles didn’t stay the same for five months, much less five decades, and that’s their essential nature, to innovate. You could chalk up the Beatles’ split to there simply not being anything more to discover within the rock combo genre. What’s happened since that wasn’t a technological change? Arena rock? Disco?

Dylan’s going electric is a Beatle-like leap, a Beatle-like change, but he did it once; you could say that his turn to roots music after his motorcycle crash was another leap, but to my ear it’s a pretty small one — it’s not like Beatles For Sale to “Strawberry Fields” in two years. Or “Strawberry Fields” to “Mother Nature’s Son” in 18 months; or “Mother Nature’s Son” to Abbey Road in another 18 months.

This isn’t to dismiss the quality of something like “Satisfaction” or “You Really Got Me” or “Mr. Tambourine Man” (or the LP I’m listening to now, Odyssey and Oracle). But it’s pretty much impossible to think that these pieces of music would’ve reached a mainstream audience — heck, they may not have even existed — had not the Beatles paved the way, commercially and musically. Take any scene you like: white-boy blues, the mods, folk in America; had the Beatles not existed, and not refashioned pop culture from November 1963-November 1964, there’s nothing to suggest that those worthy genres would’ve reached anything like the mainstream audience that they did. If they could’ve, they would’ve, and Beatlemania wouldn’t have been necessary. In this alternate universe, the Beatles are like a really good version of The Hollies. But they were clearly so much more than that.

I mean, try to imagine the 60s without the Beatles — we don’t like to admit it, but it’s impossible. Over and over, the Beatles are the spark, the essential change that allows other genius to flourish. We know what Jimi Hendrix was, before the Beatles — an eccentric sideman working the Chitlin Circuit; but after the Beatles demonstrated the market, and gave him a place to go and an audience to serve, Hendrix was inevitable. You could say the same thing about Dylan going electric — there was nothing about Dylan, pre-Beatlemania, to suggest that he was going to get a Strat and write pop songs. After Beatlemania, though, that was the obvious thing for him to do.

Innovation-wise, the only competing sound that holds a candle to the Beatles is Motown. It’s impossible to imagine 60s pop without Motown, just like it’s impossible to imagine it without the Beatles, and the stylistic distance those artists cover, from 1963-70, is nearly as vast. But everybody else — and this even includes the Beach Boys who (unlike the Stones, Kinks, etc) had carved out their own mainstream audience prior to Beatlemania — simply do not innovate at anywhere near the clip as the Beatles did. The Beatles changed as fast as Dylan did in 1964-66, or Brian Wilson in the same period, but kept it up from 1963-69. It’s uncanny. As I get older and have a better sense of how short six years is within an artist’s career, it’s almost inhuman.

Still your opinion is, I find, the more popular one, and I think it’s because we rock fans need to feel like rock’s artistic palate is vast — that everything wasn’t done by the Beatles first, and best, fifty years ago. As much as I like celebrating the Beatles, I’d like it even better if other artists could really match them. But they can’t.

Someone had to get to all that stuff first, and the Beatles were suited for doing just that. Unlike Dylan or Wilson or Davies, they were a collective of geniuses; and this collective was restless in a way that few artists are. It was their nature to get to the unexplored territory, plant the flag in the name of pop, and then move on, leaving musicians committed to that specific form to investigate it more fully.

Delighted that my post was as irritating as I hoped it’d be – I figured that if I relativised the Beatles’ achievements a bit I might get an interesting discussion going, and so it’s proved! Thanks Mike.

We agree more than we disagree. Fundamentally, we both think the Beatles are the best thing ever, by far. It’s just a matter of degree. It seems you see a slightly larger gap between the band and their peers than I do – so much so that you probably wouldn’t refer to them as “peers”.

The Beatles certainly had everyone beat when it came to covering a vast amount of ground, and staying right on the pulse year after year (something Bowie was to prove almost as good at later. But the Fabs did it first). And their 1963-4 work did indeed pave the way for all that followed. Like you say, it’s practically inhuman.

But every year from ‘65 on would see an upstart or two releasing game-changing stuff a few months before the Beatles got around to their latest masterpiece: electrified Dylan in ‘65, the Byrds and Zappa in ‘66, Hendrix and the Doors in ‘67, Jeff Beck in ‘68, the Who and Led Zeppelin in ‘69. What the Beatles did was absorb the changes in the air instantly and use ‘em to produce better music than anyone else was capable of. Where others burned brightly and faded out, the Beatles were unique in making every single year of their career count.

That said, I don’t agree that the other giants found a sound and stuck to it. Sure, the Byrds were a “jangle” band, but they tweaked that jangle so thoroughly they practically invented psychedelia with it (“Eight Miles High”). As for the Stones, Starostin can defend ‘em a lot better than I can, but I think they innovated a lot from 1965-6 and then carried right on taking creative risks. Epic soundscapes on Let It Bleed, epically creepy ballads on Sticky Fingers and epicness in general on Exile (granted, that one’s all Americana, but there are a lot of genres within Americana). Speaking of Americana: after his motorcycle crash Dylan basically created the genre’s modern incarnation with the Basement Tapes, while John Wesley Harding got the country rock ball rolling the same year. Both had untold influence. (Admittedly Dylan never innovated again after ‘67.)

And the Who? You’re talking about a band that popularised the power chord, revolutionised power pop, invented punk and fundamentally altered the way every single instrument in the rock combo was used (including the voice) – on their first album. The next album introduced the idea of the ten-minute composite song – the precursor to all prog rock. Tommy, of course, was the first well-known “rock opera”, but they sure didn’t stay there. Next year they made the best live album of all time, a record that sounded nothing like Tommy. And the year after that they pioneered both arena rock and electronica in the same track (“Baba O’Riley” is the first song to use programmed synth lines). 1965-71 ain’t a bad run; same length, in fact, as the Fabs’ 1963-69.

All through the Beatles’ career there were whole realms of music that they wisely left others to excel at. They left hard funk to James Brown, prog to Yes, psycho jamming to Floyd and the Nuggets kids, and post-’66 live prowess to a ton of better-qualified bands. They were great at most things, but in these crucial areas it was far from them-and-everyone-else.

Finally, though I’ll always be a ‘60s freak at heart, I think an awful lot happened in music after the Beatles split. I don’t think there’s a clear distinction between technological and purely musical change in rock ‘n’ roll – you don’t get from “You Really Got Me” to Led Zeppelin I without serious developments in hardware – so Low, Remain in Light, Achtung Baby and Kid A all count. Then there’s New Wave, punk, metal and the rest. None of ‘em hold a candle to “Waterloo Sunset”, but they’re still changes.

P. S. I agree that a lot of people want to diminish the Beatles in order to make room for everyone else, but I’m a complete and utter fanboy who would love nothing more than for them to have done everything first and best, from raga-rock to gangsta rap (er, scratch that last one). Sadly, intellectual honesty compels me to admit that they were as often followers as leaders. But you could say the same about any great band. It doesn’t stop the Fabs from being the greatest we’re ever gonna get.

P. P. S. Well, I just gave away a large chunk of my next post. Looks like I need a new idea

Justin, I didn’t find your post irritating in the least; and I don’t really disagree — but I do differ, if that makes any sense. You believe that the Beatles were surrounded by groups and individuals that would release “game-changing” stuff, which they would then synthesize. I think that’s true. But to me, the much more germane point is that the entire game was created by the Beatles, and was utterly dominated by them from 1963-70. The others were innovating within a structure that was created by the Beatles, and was consistently enlarged and deepened by them for as long as they were a functioning unit.

It seems you see a slightly larger gap between the band and their peers than I do – so much so that you probably wouldn’t refer to them as “peers”.

More interesting than my personal opinion are two things: how the Beatles themselves felt (they certainly considered the other bands to be their peers); and what history has clarified in 50 years since (the other bands have turned out not to be their artistic peers). The Beatles aren’t a band; the Stones, the Who, the Doors (ye gods!), Led Zep — these are bands. And damn good ones. The Beatles were, and strangely remain, a massive cultural force, the summing up of an era, and a rite of passage for a sizable chunk of the West. Every six-year-old I know loves the Beatles. Music is the means, but the ends are much bigger.

electrified Dylan in ‘65, the Byrds and Zappa in ‘66, Hendrix and the Doors in ‘67, Jeff Beck in ‘68, the Who and Led Zeppelin in ‘69. What the Beatles did was absorb the changes in the air instantly and use ‘em to produce better music than anyone else was capable of.

I’d agree with this — though the moment Zappa is brought up, you know we’re talking about two different things. As I’ve said on this site many times, the Beatles basically created rock music as a destination for a generation of intelligent, artistic people; and their commercial success set a massive economic machine on the hunt for new talent. When Beatlemania hit, pop music was a teenaged pastime; when the Beatles broke up, it was THE defining characteristic of Baby Boomer culture.

You’ll get no argument from me about the above stuff being good, interesting art that’s stood the test of time; but to me, shrinking the Beatles down to the size of the Who or even the Stones misses the essential point about them.

And the Who? You’re talking about a band that popularised the power chord, revolutionised power pop, invented punk and fundamentally altered the way every single instrument in the rock combo was used (including the voice) – on their first album.

…then why don’t I know the name of their first album? I’m a pretty intelligent guy, fascinated by 60s music and culture, and even watched a big ol’ documentary on Lambert and Stamp last month. And this LP, which you say did ALL THAT, doesn’t roll off the tip of my tongue. So I would say to you that, while musicians (and Who fans) could make a case for what you just said, outside of those groups you’d have a much tougher sell. And that means something. I’d say it means that the Who’s accomplishments were happening within the world of pop musicians, not in the larger world. Which is the difference between a trio of good musicians, and a quartet of …something else.

All through the Beatles’ career there were whole realms of music that they wisely left others to excel at. They left hard funk to James Brown, prog to Yes, psycho jamming to Floyd and the Nuggets kids, and post-’66 live prowess to a ton of better-qualified bands. They were great at most things, but in these crucial areas it was far from them-and-everyone-else.

I think it’s pretty clear that African-American music was doing its own thing, developing concurrently with Beatle music. The Beatles did not transform Black America the way they did White America. But for the other things: I definitely hear prog in the sound of Abbey Road, and the Beatles’ bootlegs from 1967 are full of psycho jamming. As to the live thing, the Beatles could not cut it loose live for two reasons: 1) they didn’t have the equipment and support staff; and 2) nearly every Beatles concert after 1962 was a goddamn riot. Can you imagine what Shea would’ve been like if they’d possessed the equipment/support of ten years’ later? Beatles concerts weren’t like the TAMI Show, musicians kicking ass and the kids going “YAY” and getting a little sweaty; they were just this side of bedlam, and I think we have to keep this in mind. As Lennon said, The Beatles “had more power.” Why? That’s the interesting question.

I don’t think there’s a clear distinction between technological and purely musical change in rock ‘n’ roll

Oh I do. The musicians that amaze me are the ones who can either 1) create something genuinely new out of relatively simple, static technology; or 2) have such a distinctive style that you can hear it regardless of the technology. Charlie Parker is a genius because of how he played, not WHAT he played. In fact I remember a story about him having to hock his horn, and showing up at a gig with a cheap Japanese plastic saxophone. And of course he killed it.

Write your next post! I want to read it!

Wish I coulda seen that gig! As a keyboardist who’s had to play some toys in his time, I sympathise.

By the way, when I looked over my first comment I noticed that all the italics I’d used – plus a nice little winking emoji after ‘Looks like I need a new idea’ – had gone, rendering my sentiments somewhat lacking in grammar and emotion. I’m still not sure how to use the commenting system, so this comment will have to be just as grammatically dodgy and emotionally stunted. Heh.

The Beatles created the game for sure. But I think – and here I’m drawing on Starostin yet again (his old site is well worth a read by the way) – that after 1964 they didn’t enlarge on things so much as make other people’s enlargements palatable to the average record buyer. (Some see this as a putdown; I don’t.) Ten bands would make some freaky music, the Beatles would listen to it all and create a poppified synthesis, the results would be so good that a hundred other bands would translate it into even freakier work, this would influence the Fabs in turn, and so on. Hendrix did “Third Stone from the Sun”, which I love but my mother would hate, then The Beatles did “Lucy in the Sky”, which everybody likes. The Beatles did Revolver, which everybody likes, and that partially inspired The VU and Nico, which everybody pretends to like. And so on.

I’ll admit that the Who’s debut isn’t well-known today – for that matter, neither is the Stones’ debut, whose title I had to remind myself of just now – but everything I claimed for it can be heard in the still-famous singles “My Generation” and “The Kids Are Alright”. The reason I think it’s so important to big up the band’s contribution is that they possessed a quality that you don’t really find in any Beatles music: a kind of ferocious, epic group wildness that came out best in their live playing.

Whereas I’ve yet to hear a bootleg that convinces me that the Beatles were good jammers; after all, there’s a reason the stuff remained in the vaults. I’d love to be proven wrong – remember, I’m a fanboy at heart – so if you know of any examples of the guys ripping it up, just point me in the right direction! Same goes for live playing. I’ll admit that “Eight Days a Week”, with its amazingly well-restored sound, presents us with a surprisingly tight, gritty unit. But the Beatles’ approach to live work, which persisted right up to the rooftop concert – i.e. do everything just like the record, but faster – would actually have suited the punk era better than the late Sixties/early Seventies. I don’t for a minute think they could have stood up against Hendrix, the Who, Sly and the Family Stone, or basically any other act showcased in Monterey Pop or Woodstock. They could play ‘50s rock-’n’-roll with amazing power, energy and charisma. But not late Sixties hard rock.

The reason I’m harping on about this is because I don’t think that any one band can mean all things to all people, and I think the Beatles had serious limitations that other bands needed to compensate for (again, true of all bands). But where things get really interesting is the group’s legacy, which ultimately is the only thing future generations will be able to judge them on. I’m fascinated that you say that they’re still a rite of passage, and that every six-year-old loves them. I think we may have come up against a cultural divide here. In Ireland, and for all I know most of Europe, a lot of six-year-olds barely know who the Beatles are. Sure, when they grow up they get to like a song or two, but apart from musos, very few people LOVE the band the way you and I do. Instead, Ireland’s cultural biases tend towards modern pop (for the young ‘uns), Springsteen and Floyd (for the old ‘uns), Led Zep and assorted metalheads (for the headbangers) and Radiohead (for the college types). In other words, if it happened before Zep’s debut, people ain’t interested. Just pity the Stones, the Who and Dylan, who people don’t even pay lip-service to anymore. What’s the situation in the States, and how soon can I move there?

Of course, influence on others is another form of legacy. But what does modern pop sound like? A mixture of electronica, which is all derived from Kraftwerk; hook-based pop which has more to do with soundbites than the Beatles’ carefully crafted melody lines; hip-hop and rap, which are ultimately derived from James Brown’s brand of funk; other African-American genres like neo-soul which go back to Marvin Gaye; the occasional ballad, which is based on the McCartney model but has utterly degraded it; and the even more occasional “alternative rock” song, which draws on punk and postpunk far more than anything the Beatles were doing. If 90% of what’s on the radio today is derived from Kraftwerk, Grandmaster Flash, Madonna and the Ramones, then what is the Beatles’ legacy really? All I can think of is that the modern industry’s obsession with electronic special effects is a sort of twisted tribute to Pepper. Not exactly the legacy the lads were going for.

You and I may say that modern pop sucks anyway, so what does it matter – but it’s the stuff that most people listen to every day on their way to work. Alas, I don’t hear much of the Beatles in it.

Let’s also consider the Beatles’ song catalog. Not only are the band’s own performances of the Lennon/McCartney and Harrison compositions great, but I’d bet that the Beatles are the most covered group in history. Their songs have been covered extensively starting in the 1960s and continuing through today. In terms of creating a consistently strong body of songs, I don’t think anyone has bested them.

Happy New Year to all dullbloggers.

.

I see Allan Williams (the man who gave the Beatles away) has died at the age of 86.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/jan/01/allan-williams-obituary

.

In 1975 Williams wrote his autobiography, The Man Who Gave the Beatles Away, with the journalist Bill Marshall. When he told Marshall that he could not remember any more anecdotes, Marshall invented some for his approval and Williams was soon telling them as his own.

.

I’m guessing he had one very muscular leg (from a lifetime of kicking himself).

Whereas I’ve yet to hear a bootleg that convinces me that the Beatles were good jammers; after all, there’s a reason the stuff remained in the vaults. I’d love to be proven wrong – remember, I’m a fanboy at heart – so if you know of any examples of the guys ripping it up, just point me in the right direction!

.

I like this one:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7PjLtnO_bE

I think the commenters are being a little unfair to the 1963-1965 competition. It’s an accepted part of Beatles lore that it took years for John Lennon and Paul McCartney to overcome their perception of George Harrison as a “bloody kid” and a marginal songwriter—and George was born in 1943, three years younger than John and seven months younger than Paul.

Mick Jagger and Keith Richard were also born in 1943; Ray Davies in 1944; Pete Townshend in 1945; and Dave Davies, the composer of the machine gun-like guitar solos on “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night”, was born in 1947!

I’m astonished that from 1964-1967, these rank beginner songwriters were able to compose original songs that bore little resemblance to ersatz Merseybeat and have more than stood the test of time.

I have to strongly disagree that Ray Davies did not create a consistently strong body of songs. Just off the top of my head I can think of many Kinks songs that stand up to the best of the Beatles’ work, like, “You Really Got Me”, “Tired of Waiting”, “All Day and All of the NIght”, “See My Friend” (the first use of sitar-sounding music in rock music), “Sunny Afternoon”, “She’s Got Everything”, “Waterloo Sunset”, “Days”, “Lola”, “I Need You”, “Till The End of the Day”—and if you want chills up your spine, listen to this unreleased demo of “I Go To Sleep” from 1965.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G8pkG9cyBsc

For those interested, George Starostin is re-reviewing the Stones’ output on his Only Solitaire blog — his most recent Stones review is this one of Beggar’s Banquet.

J.R., the word I’d emphasize in my comment is “consistently.” I yield to few in my love of many Kinks songs, but Davies’ songwriting was, IMO, not consistently great even at the band’s peak.

.

Of course, that’s an extremely high bar, and one none of the Beatles could clear in their solo work. On their own, each ex-Beatle’s work looks more like Davies’ — some great songs, some OK songs, some duds. I don’t think even Dylan was as consistently great as the Beatles while they were together.

Nancy, you raise a good point: a lot of modern songs aren’t *songs* as such, more production jobs. As such there’s no point covering them. (Tried playing Blurred Lines on the piano once and it sounded awful.) The Beatles’ dedication to writing good, honest melodies is currently unfashionable – maybe because it’s so hard to do? – but I hope it’ll ensure the kind of longevity that Pharrell Williams will never have.

Hologram Sam, some cool ideas in that one. This one’s my favourite ‘cos it shows that Lennon could be one helluva blues player when he wanted to be: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L5CKAoy-a8c Unfortunately, he doesn’t really develop the idea and then Yoko gets involved.

J. R. Clark, that’s a beautiful tune. Sounds like singer-songwriter music before that was even a proper genre.

Thank you, Nancy. For years, I’ve had to read Kinks fans on the internet trying to elevate them to the class that the Beatles, the Stones, Dylan, Hendrix, Clapton, and (probably) the Who and (probably) Led Zeppelin occupy. They’re wrong. The Kinks had four or five amazing and innovative songs, but as a group they were far short of legendary.

Two quick thoughts at this late date: (1) “Rock Around the Clock” was every bit the rock anthem that “Satisfaction” was a decade later, so the Stones can’t be said to have invented the genre. (2) There are people who don’t love “Hold Me Tight”??

There are indeed Jonathan, including the guy who wrote it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hold_Me_Tight Gotta say, I’m with Ian MacDonald on this one.

.

As for the rock anthem question, I’ve always made a sharp distinction between ’50s good-time rock ‘n’ roll and post-Beatles rock and pop. The former is basically sped-up rhythm-and-blues, which is basically sped-up twelve-bar blues. The latter very rarely rely on the twelve-bar format, and are more adventurous with their chords and melodies. But I don’t think you need to get into all that to make the distinction – people just feel it. To modern ears, “Rock Around the Clock” et al sound fun – people still dance to this stuff at weddings – but essentially dated. Whereas the Stones are still climaxing their concerts with “Satisfaction” fifty-odd years on, and none of the clapping and cheering is ironic. Rock just has a weight to it that rock ‘n’ roll lacks.

.

Having said that, you could build a case around “Johnny B. Goode”. Sure, it’s just another jumped-up twelve-bar blues, but it’s got a rock-solid beat that isn’t based on swing, the guitar licks were copped by just about every early ’60s combo, and people still hold it in high regard.

There are people who don’t love “Hold Me Tight”??

I love the chord changes on “Hold Me Tight”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BMIFNu1wDs

Also, can’t almost every Eric Carmen/Raspberries composition be traced back to “Hold Me Tight”?

I know Paul considers it one of his lesser efforts, and yet it would have been practically the theme song of any other early ’60s band who’d invented it.

Wow, that’s a great YouTube channel. I’m sometimes surprised at how gritty the guitarwork is on early Beatles songs – particularly on With the Beatles – underneath those poppy melodies and high-in-the-mix vocals. If it were up to me I’d bring the band up on a lot of tracks; you can barely hear ’em on I Should Have Known Better.