- From Faith Current: “The Sacred Ordinary: St. Peter’s Church Hall” - May 1, 2023

- A brief (?) hiatus - April 22, 2023

- Something Happened - March 6, 2023

In the run-up to John Lennon’s 75th birthday this week, this old post of ours is getting a lot of traffic. If you haven’t read it, it’s great — and an example of the wonderfulness of Bill King’s magazine Beatlefan. And after you read it, you might head over to this thread on The Beatles Bible. [Originally posted July 20, 2010; reposted October 7, 2015.]

* * *

(Folks, in the process of answering a comment from stalwart commenter Nancy, I stumbled across this excerpted Beatlefan interview with Jack Douglas, the producer on “Double Fantasy.” I found it interesting–perhaps you will, too.–MG)

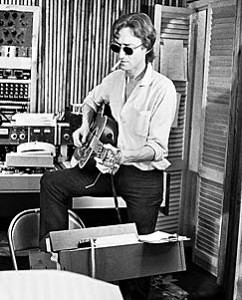

Producer Jack Douglas has nice hair.

Lennon’s Last Sessions

Producer Jack Douglas on Recording ‘Double Fantasy.’

When John Lennon and Yoko Ono decided to return to the recording studio in 1980, they enlisted an old cohort to produce the sessions. In this revealing conversation, he tells Ken Sharp what it was like ….

Producer-engineer Jack Douglas was known primarily for his work with Aerosmith and Cheap Trick before he got a mysterious phone call in 1980 that launched him into John Lennon’s ‘comeback’ recording sessions – also his final sessions, as it turned out. Contributing Editor Ken Sharp talked with Douglas recently about those sessions and Lennon’s work with Cheap Trick- one track of which is included in the new ‘John Lennon Anthology’ box set …

Q: I want to get into the Lennon “Double Fantasy” sessions, but I didn’t realize that you’d worked with John prior to that on, was it, the “Imagine” album or the song “Imagine”?

A: The “Imagine” album.

Q: You engineered some of that?

A: Yeah. Well, I was second engineer. Roy Cicala was first engineer but that was where I met John.

Q: What was that like working with John back then?

A: It was amazing and it’s so weird because we got to be friends. I was working in one studio; I was doing editing while he was tracking in another room and doing vocals. I mean, there was no way I was allowed to do vocals with him. I was way too young but he came in and I was putting stuff together and editing and he said to me “How ya doing?” You know, I’d met him earlier in the day but this was the first day and I said “OK, OK.’ I wanted to be nervous but like I said, he wouldn’t let you be. And he lit up a smoke and I said to him “I’ve been to Liverpool” and he looked at me and said “why the hell would you have been to Liverpool?” and I said well, you want to

hear this story?

Q: Is this the one on the boat? [As a young musician, Douglas and a friend stowed away on a boat In order to get to Liverpool, only to be caught and written up in British newspapers.]

A:Yeah. I told him that story. And he, like, cracked up, he was cracking up ’cause they’d read the papers about these idiots who were held captive on this boat … after that, he said “What are you doing?” I said, “Well, after this?” He goes, “Yeah”. I said “Nothing.” He goes, “You can come with me.’ So we went out, you know, and he took me to a party and he was like – see, I told him I was born and raised in New York, and he would say to me, “See that guy over there?” “Yeah” and if I knew him, he’d say, “Well, who is he? What is he?” I’d say, “Well … that guy’s an asshole. Don’t even go near him. He’ll fuck and suck your blood.” “Thanks, man.” It was like one of those kind of things.

Q: So you continued the friendship through the’ 70s?

A: Yeah, all through it. And, in fact, I was staying with him out in L.A. during the crazy period (the so-called ‘Lost Weekend”) while I was producing Alice Cooper.

Q: Oh, okay “Muscle Love”?

A: “Muscle Love”, yeah. And so I was hanging, I was hanging with him and I was doing Yoko records. All those crazy records with Yoko during which John was most of the time not allowed in the studio.

Q: Really.

A: Yeah. You know, I never let those two…very rarely when I did “Double Fantasy” did I ever have them in the room at the same time.

“Needs more cowbell, John.”

Q: Why?

A: It just didn’t work. John always wanted to get in to Yoko’s stuff and she could not bear it. It was already . . . there was already too much competition between those two.

Q: You really think there was, even then?

A: Yeah. Absolutely. And so it was, it just was when John came in and heard what she did after it was done, it was like ‘Yeah!” he’d get really excited. But if he was there …

Q: Would she be excited, conversely, with what he did?

A: Nah, “That’s good, John”, you know. But, yeah, he was always good. For her, getting her part done was the biggest challenge, you know. And I mean, he was just … I mean, for me, he was the ultimate guy to produce because he was such a true professional. He always left his ego outside the door when he came into work.

Q: What was he like as a player?

A: He was a great rhythm player. He could not play lead to save his life. Very small hands, so he had no reach at all. But man, rhythm …

Q: How did you get enlisted to produce “Double Fantasy” and wasn’t It a secret for awhile? If you can talk about how it was kept hush-hush …

A: Yeah. How did I get … I think I ran into John about six months before we did that record, maybe almost a year. I was in a health food store over on the East Side and in comes John and Sean, who was maybe 3. And the nanny and they were just coming from the YMCA where they’d been swimming. And John comes up and goes ‘Hey, Jack’ and I hadn’t seen him in years. “Jack, how ya doing? What’s happening? Oh, you’re a big producer now.’ He was always kidding me, or goofing with me. And I was goofing back with him. And he told me, ‘Why don’t you call me?” Gave me his number, and he said “Come on over to the Dakota and hang out’ and I just, I took the number and I stuck it in my pocket and my wife said to me, ‘Wow, that’s great, he wants you to come over and hang out and stuff, ‘And I said ‘Yeah, I’ll do it, you know, but, you know, maybe he was, I mean, he’s so involved with his family now and he’s kinda out of the business. I’ll call him sometime.’ I never did. I never did. Stupid, too, isn’t it?

Q: Damn, If John Lennon gave me his phone number …

A: And I never, I never called him. I always felt like ‘I don’t want to really bother him,” you know and It turns out he would have liked to have gotten that call and it was really stupid of me not to do it but anyway the thing was John was – we had a relationship and it was a good, trusting relationship and also I had that same relationship with Yoko. She also trusted me; she knew that I respected her work. And that I was a trustworthy person and John, I once asked him, I said -well into the album, we’re sitting there and mixing and I said to him “I meant to ask you, why am I doing this record with you?’ I said, “I just wanted to know…”He said, “Because you have good antenna and that works for me because you always can read me, you know what this is about’ and that s pretty cool because I always felt that was one of my strong points but it was very important to him to be able to so easily communicate with his producer. And again, like I said, because he was so without ago when he was working, he would just take a direction- If I told John, ‘For this vocal, I need you to stand on your head,” he’d say, ‘if you think that’s better, I’ll do it.’ I mean, he was like that.

Q: Were there any tracks that took a bit more time for him to nail?

A: I don’t remember. Sure … they all took about an equal amount of time. “Beautiful Boy” maybe took a little bit longer because of the chorus. Then he would double. He would double track his vocal, like in Beautiful Boy, like he would double. First shot. He loved doubling. Yeah, he was the perfect doubler. But you know, he doubled because he hated the sound of his voice. And I used to tell him, ‘John, you don’t have to double.” I mean, when he sent me the demos from Bermuda – you have to understand that these are recorded on a boom box, right, a Panasonic, and it was just acoustic guitar or in one case, piano on ‘Real Love’ and him and I think, Fred Seaman, banging on pots and pans, and he actually took the time to play those from one Panasonic to another one and double his vocal because he couldn’t bear that – I would hear these things with a single vocal.

Q: What did you think of Seaman, by the way? He’s now like this vilified character.

A: Fred, was like, you know, he just got hammered, man, I mean, there was no – John loved him and he was hired to be John’s assistant. I mean, wherever John went, he brought Fred, you know? And, I mean, Fred, he probably made a couple of mistakes. But what he got nailed for was like really off the wall. John – and I was there – John used to get things sent to him, not just one thing, he’d get a boom box, or a cassette machine, they’d send him two, three of them, or they’d just send him one – he just didn’t want all the stuff that he used to get from companies. Everybody would just want him to say “I use this,’ you know. And he was getting complimentary stuff all the time and he told Fred one day, ‘Take that,” he says, “Go in the room, Fred, and take whatever you want, man, you can have it.” And Fred went in and he took stuff and he brought it home and it was practical stuff he could use but Yoko had somebody always keeping an inventory of everything that was in that room and so, I mean, you know, Fred never, like, signed this stuff out. John told him, ‘Keep it Take it, I don’t want that crap’ and when Fred finally got nailed it was because they said, well, you know, there’s this stuff missing and you might find it at Fred Seaman’s house. And once they went there, they matched the serial numbers, it was like a grand larceny rap. And so, that’s what he got taken down on and it was really like, you know, he was there to keep a journal for John … and whatever John ever asked him to do, Fred was like right there. It was a bum rap.

Q: Tell me about the secretiveness of the sessions.

A: Well, I’ll go back a little bit here … You probably already know the story that I got flown out in a sea plane to Glen Cove to the big house out there and a seaplane right onto the beach, hush-hush, and I already knew I was being asked to do a record because I had already gotten the phone call from Yoko and John. He’s going back, he wants to talk to me about making this record; ‘Don’t say anything to anyone; just go to 34th Street, get on a seaplane and come out.’ And I came out and Yoko said to me, she handed me the envelope ‘For Jack’s Eyes Only. Or was it ‘For Jack’s Ears Only’? Maybe it was both. And she said, “John is going to call you in a few minutes.’ She said, ‘But I just want to tell you, he’s going to ask you to do a record.” I went, ‘Cool, that’s great.’ ‘You would produce it with us.’ ‘Cool.’ She said, I’m going to have a few songs on it and John doesn’t know yet.’ “OK.’ She said, ‘You can’t tell him.’ ‘All right; you tell him.’ So I had opened the tape; there was one cassette from John. And Yoko said, ‘Now here’s some of the songs’ so she handed me a thing, like a stack …

Q: Of her songs?

A: Yeah, a stack. I mean, she’d been in the Record Plant with Elephants Memory, doing demos … I wonder where those demos are; some of them were very cool. And just a stack of not cassettes, of 5-inch reels, of seven and a half, dozens and dozens of songs. And I was like shook up, ‘You gonna have a couple of tunes on this record?’ Handing me stacks and John finally called me and he said, you know, “I don’t really think I have that much stuff, you know.’ He eventually sent me another one. He said, “I think if s kind of the same old shit’ and actually that is on the tape, him saying that. ‘Most of it, I think we’ll give to Ringo” and ‘The deal is, I don’t know if this is really going to come off.’ He said, ‘I’m going to give it a try but, Jack, I’ve been out of it for a while and I don’t even know what’s going on. . So the deal was put together a band, arrange the songs any way I thought would work, I mean, as you know, if you’ve heard any of those things that are out around, you know, that things like … ‘Watching the Wheels” was like boom-jang, boom-jang, it was like fast, and almost Dylany and stuff. And he wrote me a letter saying, ‘Can you make it sound circular?’ You know, it was all these instructions I got from him and the deal was ‘Don’t tell anyone this is happening.’ We put together the band.

Q: I was curious about why you chose some of those players.

A: I wanted guys that were – well, he knew Hughie [McCracken], anyway. And he knew [Andy Newmark] and he’d played with him. So these were guys who were his contemporaries. So the important thing for me there was if John made a reference to something that was maybe from the early ’60s, or even the ’50s these were guys who would know what he was talking about.

Q: Quick.

A: Yeah, quick was very important. I did not want guys who went “duh” and I also needed guys who could read. You know, the only guy who couldn’t read was Ed [Slick]. And I brought in Ed because he’d done such fine work with David Bowie.

Let me just go back a little bit … now the band didn’t know, had no idea who they were – Tony Davilio and I did all the charts for all the songs except for “Starting Over,” which did not exist at that time, just didn’t exist. So I’m singing all of the songs to the band at rehearsal an octave lower than he would sing ‘am. And they’re like ‘Wow, great songs, Jack, but really, the vocals, I mean, who’s singing these things?” Apparently, a couple of the guys had guessed but didn’t say anything because I told them, you know, this is a secret session. They all loved it. The pay was good. They’re all getting double.

Q: Of the scale?

A: Yeah. The same with the studio. I booked the time but they didn’t know who for.

Q: The Hit Factory, right?

A: It was way out west. . . it was out of the way. No one would know. We could go in and out of there without ever being seen.

Smokin’ and strummin’, 1980

Q: So what was it like when he first walked in?

A: Well, there was one more rehearsal, the last, the night before the sessions, the last rehearsal was at the Dakota. He sits down at the Fender Rhodes and he plays “Starting Over” and I said, “Where’d that come from?” He said, “Oh, I dunno, it just kinda came.’ He said, “You think it’ll make it to this record?” I said, “Make it? ” I said, “It’s gonna be the first single.” I said, “It’s gotta be the first song on the record. You know, come on, it’s perfect.” So we recorded that, we went in and rehearsed that in the studio…

Q: It’s the first track you recorded?

A: The first track we recorded. And it just went down. Now, all this time, we’re in there, we were in there a month before there was any acknowledgment that these sessions were going on. Here was the deal: If word got out that these things were happening, it was over; it was gonna end. So, I mean, I’d tell that to the musicians …

Q: Why was it so secretive?

A: Because he wasn’t sure if he could do it. You know, he was very, very insecure about this stuff. He didn’t think he had it any more, you know. He thought he was too old, he just couldn’t write, he couldn’t sing, he couldn’t play, nothing.

Q: Do you think once he started playing again with the band …

A: It took awhile, it took awhile, there were some moments there where yeah, he was like, “I don’t know. . .” I used to have breakfast with him every morning, he insisted at 9 a.m. I’d come to the Dakota and he was always so punctual. 9 a.m., he came out his door and we would walk from the Dakota to La Fortuna on 71st Street, a little cafe. We’d sit in the back, in the garden, and have chocolate iced cappucinos and talk over what happened last night, what was gonna happen, what was going on with Yoko, everything. And then, he’d go back and he’d like take a nap and by 11 o’clock I’d working with Yoko. But we’d sit there couple of hours and talk through every and there were moments at La Fortuna when I had to say, “John, really, I swear, it’s good know, it’s good, I’m telling ya. Even the vocals, everything, you sound great.’

Q: What do you remember about the last thing you said to John or what did he say to you?

A: The last thing I said to him and he said to me was “I’ll see you in the morning at 9 a.m.’ The usual. We were going to meet and then we were mastering that next morning. We were going to master ‘Walking on Thin Ice”. It was done. We’d finished the mix so, I mean, I said goodbye to him. I saw him with this huge, with this big smile on his face and his new leather jacket that he’d gotten at The Gap a few weeks earlier which he loved, and there’s just this big smile on his face, “I’ll see you in the morning.”

Q: How long after did you hear [that he’d been shot]?

A: About 45 minutes later.

Q: How did you hear about it?

A: My wife came in and told me. We lived only a few blocks [away].

Q: You must have thought you were hallucinating …

A: I absolutely did that. I thought I was hallucinating for a good six months, good six months, it was like, gone – it wasn’t a good six months, a bad six months.

Q: Yeah, of course, of course.

A: I mean, I just flipped out.

Q: What happened after, there was a lawsuit at some point because you weren’t paid royalties? Did that get straightened out? You got paid finally.

A: Yeah, yeah. Boy, what that was. ‘Cause I waited like, two years, three years. I had a contract. I waited like three years then I finally said to Yoko, you know, ‘It’s like really like a lot of royalties probably accruing here. You know, I think it’s time like we maybe have … accountants, have somebody, you know, you don’t have to deal with it, let’s just sort it out, let our people sort it out.’ And I got like a nasty letter. Almost like “Fuck you, you’re not getting anything.” And it was like “What? I don’t get this.” And, I mean, all kinds of nasty business went down after that, you know, being followed and having people offered money to say bad things about me. None of which, even if they had succeeded, I mean, Cheap Trick was approached, none of those things …

Q: To say bad things about you?

A: Yeah, yeah.

Q: By her? By someone in …

A: Yeah, someone In her camp, ex -FBI guys, Elliot Mintz.

Q: What do you think of him?

A: Ugh. I’m not an Elliot fan. He doesn’t like me; I don’t like him … weird because John, you know, didn’t have one good word for Elliot. Sorry, Elliot. It’s like, if Elliot was coming, John was like ‘ugh’. He was more Yoko’s friend. Yeah. I can remember Elliot coming by r place, you know. Someone brought him their not knowing that it was not a good idea but I came up and it was a house I had in the Hollywood Hills … I was doing some records out there. And I so treasured these great pictures that I had, of John and 1, that I would take them with me when I was traveling. I was going to spend six months in a house in Los Angeles so in my little office I had pictures of John and 1. Amazing picture of John and I listening to ‘Starting Over’ for the first time, [while finishing up ‘Double Fantasy’] somebody from the maintenance shop, because we released it as [an advance] single. Somebody from maintenance said ‘Hey, they’re playing ‘Starting Over on the radio.” John and I went running into the maintenance shop and we’re both standing like dumbfounded, like with these stupid smiles, like kids, listening to ‘Starting Over” and there’s a little radio, me and John leaning over it, unopposed just like kids and somebody took a snap of it and so I had all these pictures and someone brought Elliot by and Elliot saw these pictures around my place …

My place was burglarized and you know what they stole? Pictures. That’s all. All the pictures were gone. Every picture I had. There must have been a dozen, really beautiful. That’s strange.

I mean, all my gold and platinum records ended up in a closet at Yoko’s. I never got them! Well, somebody [took] one out and gave it to me as a birthday present. They gave me a platinum single and a platinum record.

Q: But you worked on the record, you were very loyal.

A: One day, I asked someone, I’m not gonna mention the name because he’s still working, a loyal employee, who was also a good friend, and I asked him, “What’s the story up there?” and he said, ‘I don’t know, Jack, for some reason you are on the enemies list.’ And all I could ever think of was that I knew too much. And that it would be better – she suspected that everyone who knew a lot over the years was gonna write a book, you know, and that I would be one of these people who wrote a book and like tried to make money off it.

Q: And you still haven’t.

A: You know, I made enough just in the royalties, [they] were like 3 million bucks. It was like ridiculous and she really lost a good friend because I was really a friend to her and I really respected her art. And she always knew that, so she really lost a good friend. I pleaded with her over and over again every time that we could see each other where I could get a word in, ‘Yoko, don’t go to court. This is so silly, let’s not go to court. And when we did, it was a big public to-do. And she really was, I mean, it was a jury trial, six in the civilize, and the jury was out five minutes, came back in and the judge screamed at her, and it was like all this. Like how can you do – it was a matter with the contract. Like she tried to say the contract was a forgery, all this really weird stuff, brought in people to say that I … people like [Rolling Stone publisher] Jann Wenner to say that I was a nobody, that they’d never heard of me … and then my lawyer said “Can we talk about how many times you’ve mentioned him in your magazine?”… He made Jann read those on the stand.

Q: John was talking about touring?

A: Oh, yeah, yeah.

Q: What was his plan?

A Oh, tremendous production, including and these have to be on some of the “Lost Lennon Tapes” or whatever they call them his arrangements of songs that he said ‘we never got right,’ which were “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand”.

Q: He was gonna do them?

A: Yeah, he was gonna do them. He was going, “You know, we never – we always wanted to do something like … but it never got done exactly the way we wanted to do it.”

Q: You remember how he wanted to do some of those songs?

A: He played them on guitar.

Q: And how were they different?

A: Maybe the tempo was a little different but it was more like ideas he had for what the rest of the band was gonna do. But that was gonna -be in the show.

Q: He was gonna do some Beatle songs?

A: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

Q: I heard that McCartney or Harrison called the studio during the sessions and Yoko didn’t allow the call to be placed through.

A: No, it was McCartney.

Q: What happened?

A: Well, from what I heard and from what I heard from John as well, he was looking to get. like, hooked up with Paul before Paul went to Japan, to do some writing.

Q: They were going to write together?

A: Yeah. And … after the sessions, John never left immediately, he’d always sit in the control room and usually took a little grass. He had this old opium pipe, it was probably 500 years old, and he’d say to me, “Is it all over?” ‘Cause he would never do anything if we were working. And I’d say, “It’s over, John.” And he’d sit back and put his feet up on the console and he’d load up the pipe and sit back and light up and a few of us – I’d ride home with him because I only lived two blocks from him. And he’d start talking, you know, reminiscing about things, we’d listen to the radio and if a Beatles song came on, he’d talk about it. But the one thing – the overwhelming feeling about the things that he was saying was that he loved the guys in that band more than anybody else, you know? He was pissed off at George because George’s book had come out and didn’t mention John. You know, like, “How can he write a book about his life and not mention me? I’m the most important…” Yeah. But he loved the guys in The Beatles. He loved them. And he loved that band. And, you know, it was like his band. And I mean, the way he went on about it …

Q: And he was gonna write with Paul?

A: He was looking to get hooked up with Paul, yeah. But yeah, that call came through and that didn’t happen. And Paul went off and got in trouble. And when he got in trouble…

Q: He didn’t get the message from anyone?

A: No.

Q: Who kept him away?

A: I think Yoko probably thought … I can’t speak for Yoko. Maybe she thought it’d be a distraction. I don’t think it would have been…Who knows what would have happened. But when Paul got busted for pot in Japan, we were in the studio, when that call came in that he was in trouble, man, you oughta see John flippin’ out.

What a great interview! Thanks for posting this.

Very welcome, Eric.

I came across a lot of interesting stuff in the course of researching this book. I’ll throw it up on HD as appropriate.

Hell, maybe I’ll even try to track some people down and interview ’em. Would people like that? Any obscure Beatlepeople you want me to see if I can get to?

I know I would.

Amazing stuff — thanks for sharing it!

Elliott Mintz feels wrong, and always has.

Wow, Yoko does not look good AT ALL in this interview. I respect the woman’s art but she ruined John. And she loves to go on and on about their great love, yet she didn’t want him in her studio, she kept his from his friends, and she sought to manipulate him by not telling him her songs would be on Double Fantasy, too.

Sad.

And Elliot Mintz sounds evil.

I would

Yoko ruined John, so bad he ever went back to her after the Lost Weekend…Now she is talking endlessly about how much she loved him and that they were so great together, but the only thing she did was manipulate him and all the people who had to do with him, “robbed” Fred and other people or dragged them into court,kept John apart from the things/ people he liked, did not even tell him that her songs will be on the album… She simply couldn’t stand that not her art was important but her husband was the bigger star.

So sad.

I always hated her evil ways and as a lot of people who had to deal with her confirm her attitude to manipulate I am sure that isn’t only a myth. Maybe she even had her hands in Paul’s arrest in Japan…just a guess, but I am sure she would have been able to do that, just to keep him away from her pet!

Amazing interview, hopefully the myth “Yoko” will get some more cracks.

Astrid

Something is wrong with Jack’s timeline: Paul was busted in Japan in January 1980 and John did not start recording with Jack earlier than August that year. So John couldn’t have heard the news about that incident in the studio….

Good catch, Anon.

I remember when the record came out. People nowadays forget that it was panned in rolling stone. And I remember an interview with George Martin; he said he didn’t care for the production.

Then of course, after the murder, the rolling stone started all the tributes. But I remember how mean they were in their initial reviews.

Funny that jann wenner testified against Jack Douglas.

But when Paul got busted for pot in Japan, we were in the studio? paul was busted in january recording for doble fantasy started in August.

Saw a PBS documentary on Imelda Marcos recently. Her self-agrandizing behavior, surrounding herself with shadowy thugs who did her dirty work, while basking in the adoration of the common folk, playing the grieving widow, then reading aloud from a book she’d published of her “poems” and “philosophy” and I said to myself: “Gee, this seems so familiar. Where have I seen this behavior before?”

I remember how the Beatles were roughed up in the Phillipines; they were lucky to escape with their lives, and this was still during their witty/cheeky moptop phase; it brought an ugly dose of reality into the fun fab four story.

And yet the big lie, the mythology of Yoko continues. She is seen as the great artist, the equal of John, the great widow of the genius, who is also a genius in her own right, and anyone who dares say otherwise is villified and ignored.

Someday, somewhere, someone will discover a letter written by John, or a journal entry, where he says he can’t wait to end the marriage and get out of that prison. Or maybe not. If such a document ever existed, it was probably destroyed years ago by Elliot Mintz.

(If I had a dollar for every book I read that called Mintz a “good friend” of Lennon, I’d have a good chunk of money in my pocket. I’m sick of this big lie. All I want is the truth.)

Google “The day John Lennon, husband and friend died” by Peter Doggett

Read whole thing

“this one’s for Gene and Eddie and Elvis… and Buddy.” And Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, Elvis and Buddy Holly looked down from Rock ‘n Roll heaven and smiled.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C4C5_JQtkrc

I always thought of Jack Douglas as one of the Young Fogeys. He produced Alice Cooper and Arrowsmith? Give me a fucking break; by 1980 there was a newer wave of producers experimenting with a return to powerful minimalism. Why not Nick Lowe or Don Was? Or Chris Blackwell, who produced the B-52’s first album? But John was acquainted with Jack Douglas and felt comfortable with him, so he exited with an album that didn’t do justice his magic.

—-

In 1980 I rushed out to buy Double Fantasy, and loved some of the songs, but found the production a look backwards, not forwards. Too bloated; too polished. John Lennon as Billy Joel?

—-

I love the stripped down version of Double Fantasy, but it’s thirty years too late.

—-

Reading the above comments from 2011. I was the one who compared Yoko to Imelda. An outrageous display of bad taste on my part, but Jack’s recollections combined with what George Harrison’s sister recently said during the last fest… my opinion has not changed.

@Sam, I think Double Fantasy would’ve been 100% better if Nick Lowe had been involved in any way, but that’s just because I love Nick Lowe.

To me DF seems sleek and glossy and…kinda fat. The music is in step with 1980 (think “Gaucho”), but out-of-step with the househusband/comeback/Lennon aesthetic.

Lennon was listening to and admiring the work of Nick Lowe and Chris Blackwell, he admitted it in interviews. But he was apparently too shy to approach them.

—

Also, I think Yoko had final say over who he got to work with. Douglas was okay in her book because she knew him and he’d been sufficiently deferential to her music. (He didn’t cover his ears like some of the other engineers while she screamed.) I doubt she would have let Nick Lowe near John. She didn’t even trust Cheap Trick and so their collaboration stayed buried for 30 years (but some of their musical ideas made it to the album, even though they didn’t.) John, the frustrated magpie.

—-

It’s sad. I suspect John was ACHING to do some ballsy reggae records. He loved “Watching The Detectives” but when Jack Douglas and his hand-picked session men got through with “Borrowed Time” it sounded like something you’d hear on a Bermuda cruise ship. (from wikipedia: As he was somewhat frustrated that the band could not quite catch the reggae feel, Lennon decided to set the song aside.)

—

A few years back Keith Richards released some very powerful and minimal reggae tracks. Heavy bass and percussion. Keith was confident enough to hire people who knew how to make that sound.

Ahh, @Sam, John Lennon in 1980 was exactly as free as he wanted to be. If he was letting Yoko’s comfort guide his choice of producer — which rings very true to me, btw — he deserved the frustration. Pre-Yoko Lennon didn’t play like that, and we were all the better for it.

I found his comments on Mintz (that John didn’t really like him, and regarded him as Yoko’s friend) particularly interesting. The only real eyewitness who supports Yoko’s “house-husband” story of John’s last years is Mintz, and there are obvious issues with that. Both Norman and Coleman rely almost entirely on Mintz (with the occasional addition from Bob Gruen) to support their rose-colored interpretation of John’s life, 1975-1980. When you overly-rely on one eyewitness source, especially concerning a debatable topic, that sends up a red flag.

Then, of course, there’s the fact of Mintz’s position as Ono’s employee and P.R. guy. Coleman actually did an excellent job of analyzing Seaman’s credibility in one of the later editions of his John bio, but neither he nor Norman ever even hint that Mintz’s testimony is anything less than 100% honest; both blithely accept all of Mintz’s statements at face value, and never discuss the glaring conflict of interest his position presents. That’s lazy, misleading, and methodologically unforgiveable.

@Ruth, you’re right on with this, and it’s largely why I defend the Goldman book if only as a salutary thought-experiment. The more conventional Lennon histories fix great skepticism upon anybody whose memories might skew the official narrative — Marnie Hair, Fred Seaman, the astrologer “John Green” — while assuming that people like Elliot Mintz or bob Gruen (or indeed John and Yoko themselves) are not worthy of skepticism. Those of us who live in the world, where money talks and St. Tropez is nice in the winter and legal remedies are often unequally applied, know otherwise.

There is really very little benefit to contradicting the official narrative. (I would argue that this is usually the case, which is why official narratives can be so malign.) Not only is there no pot of gold waiting for idol-smashers, you have to be a peculiar person to both care passionately about an idol, and then enjoy smashing it. The world loved John Lennon, for a million good reasons, and I’m not surprised most of his biographers do, too. But there is also the small matter of What Actually Happened. When somebody does step out of line to contradict what we’ve all been told, I believe that in itself is worth noting; and it becomes doubly worth noting when strong pushback can be predicted beforehand. And if we dismiss Person X as crazy and/or venal, we have to consider that possibility for others, too. Better to assume that everybody’s acting rationally, if sometimes excessively.

In preparing this response, I read this article from Rolling Stone, which is really all you need to know on this issue. Even when I think it’s probably right, it’s weaselly. Its hysterical defense of Lennon’s heterosexuality is particularly noteworthy; thank goodness we seem to be heading towards a world that is marginally saner about such things. The TL;DR of it is that Rolling Stone — like Elliot Mintz, or Yoko, or John himself — is not impartial and should be taken with a grain of salt. Your size may vary.

“The more conventional Lennon histories fix great skepticism upon anybody whose memories might skew the official narrative — Marnie Hair, Fred Seaman, the astrologer “John Green” — while assuming that people like Elliot Mintz or bob Gruen (or indeed John and Yoko themselves) are not worthy of skepticism.”

And that failure to equally apply skepticism has encouraged Beatles history’s partisanship and errors. Source Analysis 101 means asking “Should I trust what this person is telling me?” of *any* eyewitness account; not just the ones whose version of events you personally dislike/disagree with. For example, when I read Douglas’s interview, I have to read it with the knowledge that he gave it A) 19 years after John’s death, which makes it retrospective (although he does say many of the same things in Goldman, interestingly enough B) and that it came after the collapse of his personal and professional relationship with Yoko. Evidently she’s the one who caused the schism, but who is to say Douglas wasn’t somewhat exaggerating the tension between John and Yoko in order to ‘get back’ at Yoko for forcing him to sue her? We can’t blindly accept what Douglas says any more than we can Mintz, although I’d conclude that Douglas is the more credible witness.

@Ruth, my cast of mind might simply be darker than yours — it’s all that Roman history — but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if Jack Douglas is telling about 1/10th of what he knows and saw. And that goes for everybody in that overheated, overmoneyed, drug- and sex-filled milieu. Baby Boomers tend to…keep things to themselves. 🙂

The truth has many enemies, and few friends; it is told only when it doesn’t cause you trouble, or cost you money. And no business is as touchy and paranoid (and has as much to hide) as show business. Lennon himself was notable precisely for how forthright he could be — how he would ignore these pressures — as in “bigger than Jesus” or “Lennon Remembers.” Lennon’s moments of unpredictable honesty are one reason we all loved him so, even when we suspected that he was only telling us part of the story. Which is what makes the murkiness of his later life so offputting, to me — I don’t even care whether he slept with ladyboys four at a time, it’s more an existential pain: if we can’t know the truth about John Lennon, that magpie, that compulsive over-sharer, who can we know the truth about? And if we can’t know the truth about anyone famous, isn’t all of popular art just an exercise in crowd psychology?

Sure, Douglas could be shading negative to “get back” at her — but would you antagonize a woman with practically unlimited resources, who’d shown herself all-too-willing to sue you (frivolously, as it turns out)?

Who the heck is Yoko Ono? What makes her tick? Any historian examining this topic has to determine this, and nobody has. Why is she, a very famous person with tons of primary source on her (interviews, art) so fundamentally unknown? I’d argue that in 2015, it’s precisely this unknown quality that makes her an irritant to some; in a country that celebrates Donald Trump, just having money and being abrasive aren’t necessarily strikes against you. Why do things that were widely considered grounds for a lawsuit in 1988 — John’s penchant for physical violence, his possible bisexuality — suddenly come out of Yoko’s own mouth in 2008? What’s real and what’s PR here?

Beatles history has its fair share of partisanship and errors, but the lacunae and disputes that exist today are not, I think, the result of partisanship and errors. They are the result of Yoko’s intense desire not to be known by the public in any way that she does not meticulously manage; and for a certain “chill” caused by power and money. One need look only at the differences between the “Director’s Cut” of the Anthology and the final one, to see this in action. And why? The fact that Paul and George resented Yoko’s presence in the studio — this is not news. Why not simply say, “They resented me, I was probably overbearing, it was weird, we were all young and on drugs”? There’s a commitment to narrative-shaping that I find just so disheartening. It won’t keep people from disliking Yoko, it will only make the rest of the history less accurate and more partisan.

We all read the Davies book and say, “it’s a whitewash,” secure in the knowledge that we know better today — but there’s nothing structural to suggest the current version of the Beatle myth is any closer to the truth. The same fundamental pressures that existed in 1968 existed in 2007; just like Davies, Norman was writing to sell books, and wanted to add in just enough salacious material to move units, but not shock fans so much they wouldn’t buy it. What was shocking was different between 1968 and 2008, but it’s good to remember that the fundamental pressures are always to the positive side, because these products are first last and always commercial. Adversarial bios are simply a losing proposition. Something like Mommie Dearest is the exception, not the rule — and was a success precisely because, by 1978, nobody really gave a shit about Joan Crawford. As long as people still give a shit about John and Yoko, we’ll never know the real story. (sigh)

Why do things that were widely considered grounds for a lawsuit in 1988 suddenly come out of Yoko’s own mouth in 2008?

I’d never heard that (I was preoccupied with other things in 2008, like watching my savings account evaporate); do you have a link?

@Sam, just search for info on the Norman bio. You’ll see that the book’s entire PR push was built on the kind of “revelations” that would not be out of line with Goldman’s portrait — physical violence and cruelty, homosexual feelings towards Paul, and pondering incest on the 9/5/79 diary tape — but very much out of line with the standard portrait.

Here’s Norman’s bit about John’s supposed homosexual attraction to Paul:

Pretty thin. Now, clearly, as homosexuality becomes more accepted (especially among younger people), the possibility that Lennon was bisexual is simply less shocking than it was in 1988. Each era, apparently, gets the John Lennon it can tolerate — but that only underlines the issue at hand. Goldman’s book is snide and antagonistic in its tone — but the above quote is exactly the kind of thing upon which Goldman built his portrait. In 1988, such stuff gave Yoko the vapors; twenty years later, it’s coming out of her own mouth.

What’s her motivation? Taking a swipe at her ex-husband? (In the quotes I’ve read — sorry, I can’t remember where — Yoko doesn’t characterize John’s bisexuality as a good thing; she’s not applauding him for queering Beatlehood, or even showing a kind of contemporary heteroflexibility. To Yoko, John’s wanting Paul seems to be giving into a kind of ‘subservient, pleading’, i.e. feminine, weakness.)

Or is it pure put-on? Or is Yoko subverting the world’s image of John and Paul? Or maybe her husband was simply obviously bisexual, and once everybody drops the hysteria, it’s just there, and since she lived with and loved him, it comes out in her memories.

Can you imagine our portrait of Paul or George or Ringo shifting like this? I can’t. And to be honest, I don’t think John was all that more outrageous or complicated than the other three were/are. I think we’re getting set up for something — Yoko’s memoir, perhaps? A posthumous doc dump? The whole thing makes me think we’re getting played.

“Who the heck is Yoko Ono? What makes her tick? Any historian examining this topic has to determine this, and nobody has.”

Because Yoko has been so unwilling, any biography of her would have to include an enormous amount of speculation, and a lot of historians simply don’t want to go there. A bio of Yoko wouldn’t sell as well as one of John/Paul/George, etc; add in the fact that she’s still alive, litigious, and there’s little-to-no academic benefit for her biographer, and that’s why we’re stuck with poorly researched, partisan jobs.

I’d argue that any assessment of Yoko’s character *has* to include her constant claims to victimization. Her and John’s breakup-era narrative depends on portraying themselves as the victims: of the Eastman’s, Paul, commercialism, squares, the establishment, racists, misogynists, etc. Even after the narratives shifts and facts indicate otherwise, John and Yoko are still claiming victimhood: of Klein’s manipulations, of a constricting press, of proscribed gender roles, commercialism. But they take their victimization to the extreme, in that no one else is allowed to have been victimized. I’ve never seen an admittance by Yoko that perhaps their treatment of Julian was less than stellar; or that John was displaying massive hypocrisy, lambasting Paul privately and publicly as a chauvinist for his treatment of Yoko while writing letters attacking Linda’s “petty little perversion of a mind,” publicly mocking her looks, and predicting that Paul and Linda’s marriage would only last two years. Yoko even identifies John as the victim of “How Do You Sleep,” criticizing fans for “attacking” John for writing it when they simply asked for an end to the public feuding. That victimization continues throughout the decades, as does that utter refusal to acknowledge something as basic as you said, “Maybe my being in the studio, all the time, wasn’t the best thing.”

As for why Norman’s work is so “Goldman-esque” in its portrayal, I don’t see it as a major departure from Norman’s previous methodology. There’s an equal amount of speculation in Shout!; the difference is that much of that same quality of evidence (hearsay, unverified eyewitness testimony, etc) is negatively slanted against Paul and/or George. In the bio, it involves John as well. I would guess that Norman included the violence, as well as the tape about John and his mother, because he had to: those facts were already out there, and if Norman failed to include them, the book would have been dismissed as a whitewash. Norman couldn’t write Coleman 2.0: there were too many eyewitnesses, too many documented incidences. In addition, Norman was admittedly attempting to “make it up” to Paul by portraying him in a more favorable light, and much of the “Saint John” narrative collapses once Paul no longer serves as his shallow, inferior foil.

As for his writing on the John/Paul homosexuality issue: I think its worth noting that Norman’s speculation on that subject (evidently) pre-dates his interviews where Ono revealed it to him: He mentions it in the 2002 edition of Shout!, when discussing John’s out-of-proportion bitterness regarding Paul both during and after the breakup: “It almost suggests that, beneath the schoolboy friendship and mutual musical business, lay some form of homosexual adoration that John himself never fully realized.” Perhaps Norman broached the subject first, which is why Ono expanded on it.

@Ruth, you are awesome. I love your comments. Thank you for playing.

I think you’re right on about this, and I think it’s a big part of John’s attraction to Yoko. Anger was at the core of his personality, but as he became more and more successful, it was harder and harder to work up a good head of righteous indignation. (I think that’s why he got interested in politics.) Yoko’s worldview gave him permanent victim status, and he took to it with relish. John Lennon was the original “white knight“: “We men are such chauvinist pigs.” What do you mean WE, Kemosabe?

Here’s the other thing at work here, and while it’s touchy to talk about, it’s something that can’t be underestimated: people feel so damn sorry for Yoko over what happened to John. How could you not? I think that’s why she’s gotten a pass on a lot of things — like her deplorable treatment of Julian, or her haughtiness regarding song credits and Beatle history in general. It seems unkind.

Since 1980, substantive criticism of her behavior is totally radioactive, especially among the New York-centered intellectual classes — the reviewers and writers and critics. Internet commenters can and do bleat ignorantly about her music being “noise” or some such; but an actual grownup-to-grownup appraisal of her behavior — as people do constantly with Paul, for example — is simply nowhere to be found. Her privacy keeps everything queerly personal, and I which it were otherwise, because that is a diminution of her. One should be able to critique the artist or businessperson or public figure, without piling yet another unfair injury upon the long-suffering, appallingly wronged widow.

Mike, to your point about Lennon’s need for righteous indignation, Allie Brosh sums up this kind of need brilliantly in “Menace,” posted on her blog Hyperbole and a Half:

.

“The thing about being an unstoppable force is that you can really only enjoy the experience of being one when you have something to bash yourself against. You need to have things trying to stop you so that you can get a better sense of how fast you are going as you smash through them.”

.

I’m also struck by how similar Yoko’s need to control image and press perceptions seems to Paul’s. It certainly says something about John that the only two people he said he worked with as full artistic collaborators shared this tendency.

[Hyperbole and a Half link, for those interested: http://hyperboleandahalf.blogspot.com/%5D

[…] Jack Douglas in Beatlefan, 1999 […]

Another spam link detected! In the paragraph after “Q: Do you think once he started playing again with the band …”

The dedication of these people to infest the site is amazing

In googling Jack Douglas, I came across this 1999 rec.music.beatles thread about this interview. (Yes, the thread has a… questionable title).

But there’s one interesting tidbit. Danny Caccavo (audio engineer who worked at the Record Plant) wrote,